What is a Cosmetic?

Most of us use cosmetics everyday and we “know them when we see them”. However, if I was to ask you whether you thought your toothpaste, suntan lotion, lip balm, mouthwash or anti-dandruff shampoo were cosmetics, I might get a range of opinions.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines cosmetics as:

- Having power to adorn, embellish or beautify (esp. the complexion).

- That affect appearance only; superficial; spec., intended merely to improve appearances.

(OED, 1991, p. 343)

A key point about the OED definition is that cosmetics are superficial rather than therapeutic agents. Cosmetics are not ‘over the counter’ (OTC) or prescription drugs or drug additives, their role is merely to improve your appearance. This seems straight forward until you look at the full range of products that might fit this definition.

- soaps and other body cleansing products;

- creams, lotions, face masks, powders and colours for the skin, eyes and lips;

- shampoos, lotions, oils, waving agents, fixatives, bleaches, dyes and dye removers for the hair;

- lotions, polishes and colours for the nails;

- hair removers;

- skin bleaching and skin tanning preparations;

- toothpastes and other oral care preparations;

- antiperspirants, deodorants and other personal hygiene products;

- perfumes and other aromatic substances.

The list above is a testament to the incredible variety of beauty products on the market. However, this boon for consumers is a problem for legislators; concerns about safety and fraudulent advertising claims saw cosmetics becoming increasingly regulated in the twentieth century and this required law makers to legal define them. Unfortunately, regulators in different countries defined cosmetics in different ways. Two examples are given below:

United States: Defines cosmetics as “(1) articles intended to be rubbed, poured, sprinkled, or sprayed on, introduced into, or otherwise applied to the human body or any part thereof for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering the appearance, and (2) articles intended for use as a component of any such articles; except that such term shall not include soap” (Federal Food & Drug Act, 1938, p. 32).

European Union: Defines cosmetics as “any substance or preparation intended to be placed in contact with the various external parts of the human body (epidermis, hair system, nails, lips and external genital organs) or with the teeth and the mucous membranes of the oral cavity with a view exclusively or mainly to cleaning them, perfuming them, changing their appearance and/or correcting body odours and/or protecting them or keeping them in good condition” (The rules governing cosmetic products in the European Union, 1999, p. 7).

Definitions are important as they draw a legal line between cosmetics and drugs, determine labelling requirements and other product standards, and proscribe the types of claims manufacturers can make for their products. This distinction is being blurred by a group of products often referred to as ‘cosmeceuticals’; however, this term has no legal definition and is not recognised in any current regulations.

See also: Ingredients Lists

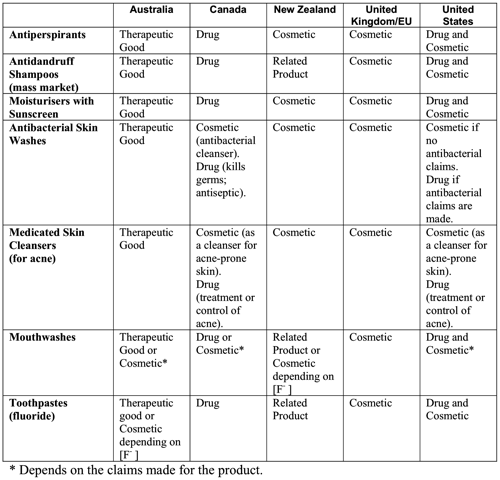

A report produced in Australia in 2005, as part of changes to its cosmetic regulations, includes a good example of some of the definitional differences between jurisdictions as they were then:

Above: 2005 Comparison of how products are regulated in different countries (Commonwealth of Australia, 2005, p. 20)

The new Australian regulations developed from the 2005 review redefined the following products as cosmetics:

- Antiperspirants.

- Anti-dandruff shampoos (unscheduled).

- Sunscreens with an SPF that is less than 4.

- Moisturisers with secondary sunscreen.

- Antibacterial skin washes.

- Anti-acne skin cleansers.

This change reduced the regulation of these products in Australia as well as the way they could be packaged and advertised. One consequence of this change was that a number of products that had known physiological effects on the body were now considered cosmetics. In the old regulations, deodorants, which masked body odour with perfume (i.e., affect appearance), were defined as cosmetics, whereas antiperspirants, which inhibit perspiration (i.e., affect body function), were classified as therapeutic agents (i.e. drugs). As a result of the review, both were now legally redefined as cosmetics in Australia.

The changes in Australia are part of a general trend. Regulation is expensive both for governments and industry. Just as there has been a steady movement of drugs from ‘prescription only’ to ‘over the counter’ (OTC) and from pharmacy to supermarket, we can also expect some additional easing with cosmetics. The global nature of the cosmetic market is putting pressure on legislators to iron out differences between jurisdictions and relax regulations regarding the use of therapeutic agents in cosmetics. However, we should remember that one of the main reasons for regulating cosmetics is to ensure that the products are safe. The twentieth century saw a number of examples of potentially harmful drugs being incorporated into cosmetics – e.g., face creams containing hormones – that were stopped through regulation.

See also: Hormone Creams, Oils and Serums

Updated: 6th June 2017

Sources

Are Some Cosmetics Promising Too Much?. (2015). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved March 31, 2015, from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/UCM439333.pdf

Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. (1938). United States Government. Retrieved January 12, 2015, from http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2010-title21/pdf/USCODE-2010-title21-chap9-subchapII-sec321.pdf

Regulation of cosmetic chemicals: Final report and recommendations. (2005). Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved July 24, 2009, from https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/consult-cosmetics-regulation-050303.pdf

The rules governing cosmetic products in the European Union. (1999). European Commission. Retrieved January 12, 2015, from http://www.leffingwell.com/cosmetics/vol_1en.pdf

Winter R. (2005). A Consumers dictionary of cosmetic ingredients (6th. ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press.

Some cosmetics are easy to identify, some are not.

Valid cosmetics claims as suggested by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2015. “Products intended to cleanse or beautify are generally regulated as cosmetics. Products intended to treat or prevent disease, or affect the structure or function of the body, are drugs. Some products are both cosmetics and drugs.” (“Are Some Cosmetics Promising Too Much?, ” 2015).