False Eyelashes

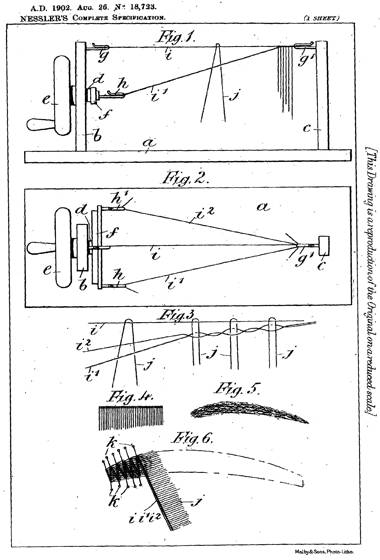

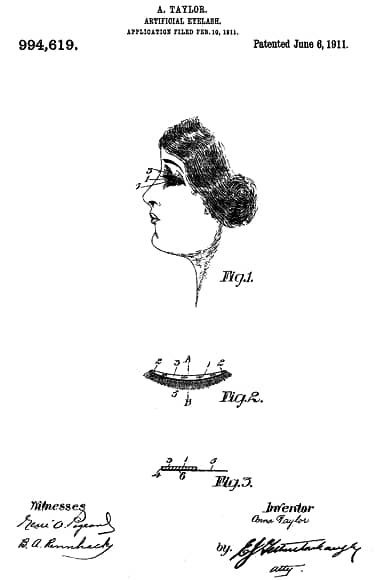

People credited with inventing artificial or false eyelashes include Karl ‘Charles’ Nessler (1902), Anna Taylor (1911), D. W. Griffith (1916), George Westmore (1917), and Max Factor (1919). However, we have to go back to the nineteenth century to discover their origins.

Sewing in eyelashes

In the 1870s, newspaper reports began circulating that someone in France had developed a method for fixing false eyelashes.

It is whispered that a genius has discovered a plan for fixing false eyelashes.

(The Shefield Daily Telegraph, Saturday, March 18, 1871, p. 2)

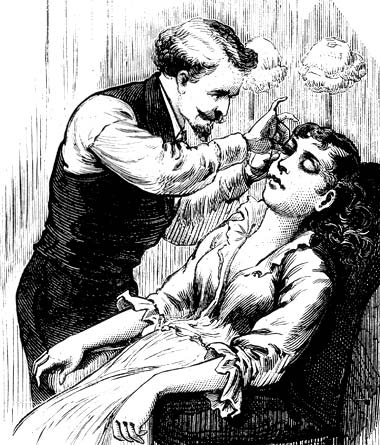

By the 1880s, newspapers indicated that this Parisian beauty technique involved sewing hair into the eyelid.

Truly the inventions this nineteenth century has brought forth are wonderful, but surely one of the most marvellous is this:—The Parisians have found out how to make false eyelashes. I do not speak of the vulgar and well-known trick of darkening the rim round the eye with all kinds of dirty compositions, or the more artistic plan of doing so inside the lid. No, they actually draw a fine needle, threaded with dark hair, through the skin of the eyelid, forming long loops, and, after the process is over (I am told it is a painless one), a splendid dark fringe veils the coquette’s eyes.

(The Evening Telegraph, Thursday, January 5, 1882)

It might be thought that these hearsay reports were untrue but there are later mentions of London hairdressers supplying false eyelashes using a procedure took three days. This suggests that they were also sewing in false lashes.

Several West End hairdressers supply false eyelashes. The process of attaching them takes three days, and costs twelve guineas.

(The Yorkshire Evening Post, Thursday October 13, 1892, p. 3)

Strip lashes

A less invasive method of applying false eyelashes was to glue human hairs on a backing strip and then fix this to the upper eyelid. These appear to have been available in Europe at least as early as the 1870s. As Goodman notes, the idea may have originated on the stage using surgical tape or an adhesive plaster, both widely available through the nineteenth century.

The earliest style is still used by show people adhesive tape with hair stuck to the underside, or the hair may be laminated between two layers of adhesive tape. It may be too bulky, heavy and easily noticed for general use, but it is suitable for use on stage where it is viewed from a distance.

(Goodman, 1958, p. 734)

Forms used off the stage could be purchased from hairdressers/wigmakers who constructed and used the many different types of hair pieces fashionable at the time. Some also made mustaches, whiskers and eyebrows for theatrical and other clients and a few also made false eyelashes. These false eyelashes were not generally available over the counter but were made up as required. For example, Willy Clarkson [1861-1934] – a famous English wigmaker who ‘wigged’ most the leading lights of the English stage and made-up many members of the British aristocracy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – made his own false eyelashes when the need arose.

One of the most difficult cases that I have ever had to deal with was of a lady, who, as the result of illness, had lost all her hair, and also her eyebrows and eyelashes. The hair and the eyebrows were easily replaced, but the eyelashes were a different matter, and she grew quite thin and ill through worrying over their loss. When at last she came to me about the matter, I at once recognised the difficulty of the task, but undertook to do my best by her. You can imagine how great were my difficulties when I tell you that I had to make twenty different attempts before I hit upon the right method of accomplishing my object. The hairs had to be fixed with the utmost care on the finest possible foundation into which they were inserted one at a time under a very powerful magnifying glass, but the result was worth the trouble. When all was ready the lady drove up with her husband, and left him in the carriage while the lashes were being adjusted.

You have no idea what a difference the lack of eyelashes makes to a person’s looks, and I was nevermore surprised than by the difference in this lady’s appearance before and after I fixed on her lashes. She had driven up a plain woman, she went away a beauty, and I shall never forget the look of surprise on her husband’s face when he saw her return to him as she had been before her illness.(Willy Clarkson in The Hairdresser and Toilet Requisites Gazette, July 1909)

By the late nineteenth century, ready-made boxed pairs of false eyelashes were being sold in some of the larger cities. Unfortunately, the earliest records I have for commercial false eyelashes only date from the twentieth century.

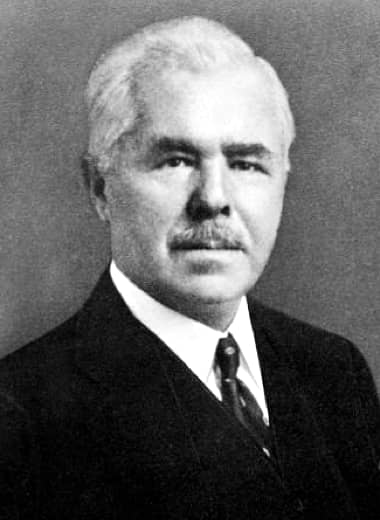

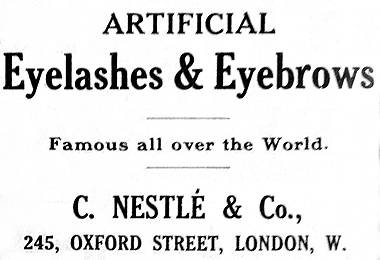

Charles Nessler

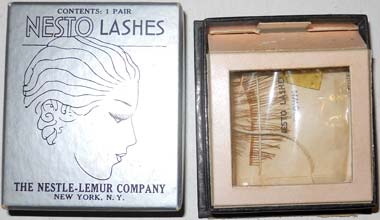

In 1901, German born Charles Nessler moved from Paris to London and opened a hairdressing salon in Great Castle Street. In 1902, he also patented a ‘new or improved method of and means for the manufacture of artificial eyebrows, eyelashes and the like’. Around 1903, he began selling boxed pairs of artificial strip eyelashes made from human hair attached to ‘fish-skin’ – also known as isinglass – made from fish swim bladders. Later versions of his strip lashes, known as Nestolashes, were available in Brown, Dark Brown and Black shades.

The latest aids to beauty are art eyelashes. They are the invention of a hair specialist in Great Castle Street, London … On the counter were cardboard boxes containing countless cards. On each card was a delicate set of lashes attached to a scarcely visible strip of fish-skin. A small bottle containing a “skin fluid,” patented in America, and two cards complete the outfit. The eyelashes are 2s. 6d. per pair for “society wear,” and 1s. 6d. per pair for theatrical wear. “On our customers first visit,” said the manager, “we fix the skin on the eyelid with the fluid, and the false lashes mix with the lashes of the lady. It is beautiful—beautiful.” The lashes last ten days usually, but twenty days with care. The manager declared that the 2s. 6d. pairs were proof against even a prolonged fit of hysterics.

(Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 1903)

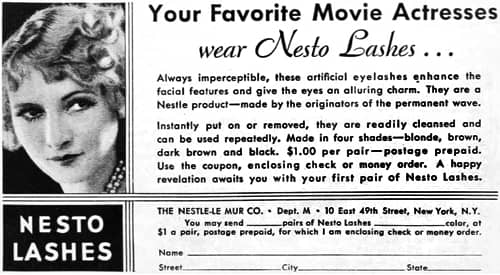

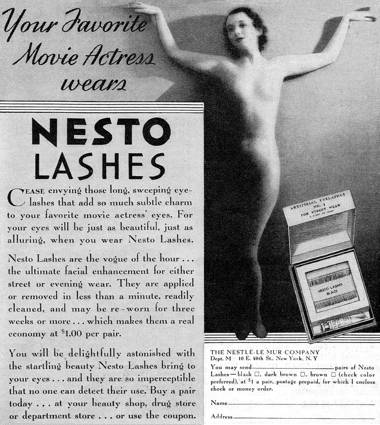

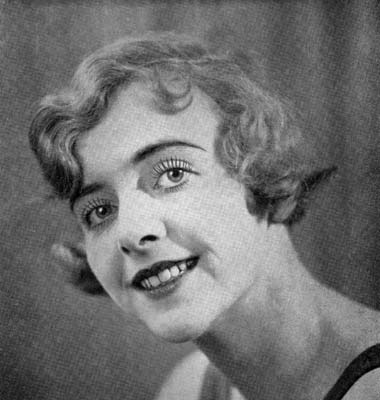

Although strip lashes were available in the early part of the twentieth century, they only became fashionable in the interwar years. The probable reason for this was the rise of Hollywood. As it began to dominate the global movie industry it allowed make-up artists like Max Factor and the Westmore brothers to spread their visions of glamour world-wide. Women who wanted to emulate the eyes of film stars like Greta Garbo could use mascara, but they also had the option of applying false eyelashes from suppliers like Nestlé-le Mur or Max Factor.

Above: 1932 Nestlo Lashes.

The strip lashes from this period were made from natural hair, mohair or artificial hair attached to isinglass, silk, gauze or some other transparent or flesh-coloured membrane which was glued on to the eyelid with an adhesive. Although they could be applied at home many women opted to have the treatment done at their local beauty salon.

The link above is to a British Pathé film which shows strip eyelashes being applied in 1930.

The adhesive, which is packed either in a small phial or a tube, is used lightly on the under-side of the silk strip. This is allowed to dry for a moment, so that the liquid becomes merely sticky. It is then ready to adhere to the skin. The client should close her eyes, and you attach the strip first on the inside near the nose. The strip must be placed along the upper lid as close to the growing lash as possible, and smoothed away from the inside towards the outside of the face. When it is in position the corner of a face towel should be dampened and held over the silk strip, pressing it firmly to the skin. This sets the adhesive. If eyeshadow is to be used, it can be applied over the silk strip and on the lid. It is best to use a dry form of eyeshadow if artificial eyelashes are worn. The necessity for any cosmetique on the lashes will depend upon the natural colour and the colour of the artificial ones. If they are a pretty good match, it will not be necessary to use any colouring, for the lashes will appear thick and long. The natural lashes should be brushed upwards, so that they mingle with the artificial ones.

(The Hairdresser and Beauty Trade, 1934)

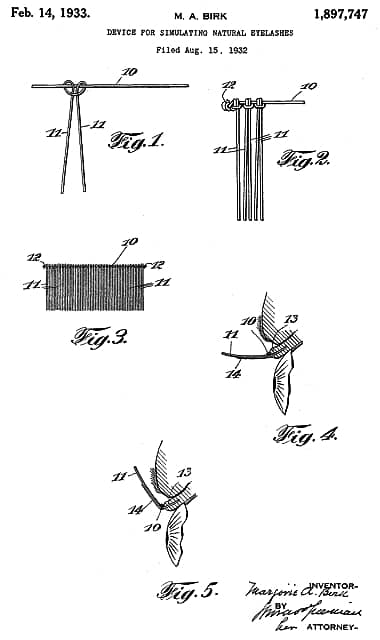

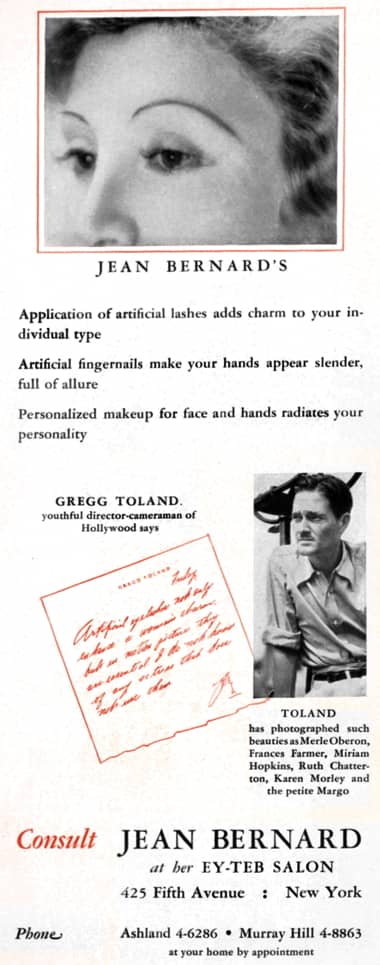

A variation on the conventional strip lash was patented by Marjorie A. Birk of New York in 1933. Rather than gluing lashes to a strip of material, Birk knotted natural hair to a filament of cotton, linen or silk or some other material. Birk used her patent to found Ey-Teb, a company that operated successfully in the United States and elsewhere for many years. However, Goodman suggests that her method had been known in Europe before 1933, and that eyelashes made using it were available in America before Birk took out her patent (Goodman, 1958, p. 735).

Above: A box of Black Ey-Teb Strip Lashes with a bottle of adhesive showing the lashes attached to a fine filament.

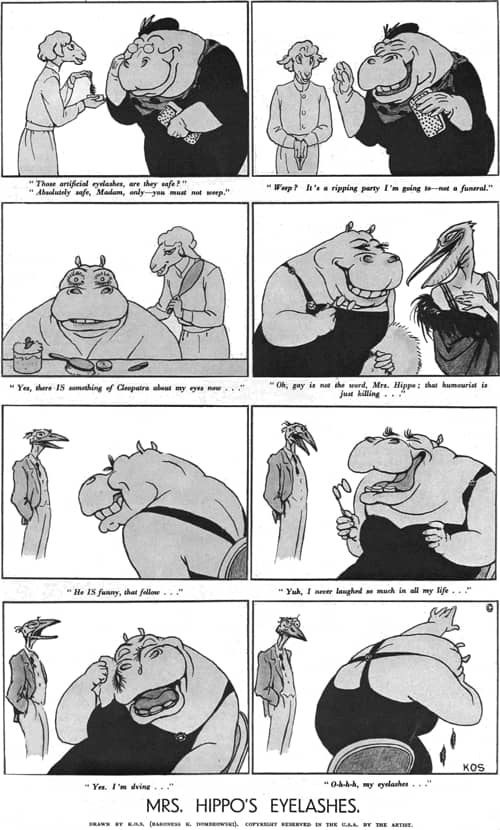

Strip lashes were not without their problems. They came in a limited number of shades, so colour matching was an issue, and they had a tendency to lift off on the outer edge of the eyelid or fall off altogether, a problem they shared with the earlier nineteenth-century strip lashes.

False eyelashes are not the perfect inventions they are represented to be. I saw one floating in a cup of tea the other evening, and the lady went on toying with the saucer and conversing, and never for a moment suspected that the left side of her face, by contrast with the right looked rather as if it were slowly recovering from a small explosion of gunpowder.

(The Royal Cornwall Gazette, 1879)

The problem was common enough to be satirised in a British newspaper in 1933.

Above: 1933 Mrs Hippo’s Eyelashes.

Also, as the angle in which eyelashes grows varies in different people, some women found it hard to get the curl in their false eyelashes aligned with their real ones. The invention of the Kurlash eyelash curler (1924) by Charles W. Stickel [1889-1943] and William E. McDonell [1882-1941] must have been a great help in correcting any misalignment.

Above: 1934 June Knight using a Kurlash eyelash curler to curl her false eyelashes.

See also: Kurlash

Eyelash grafting

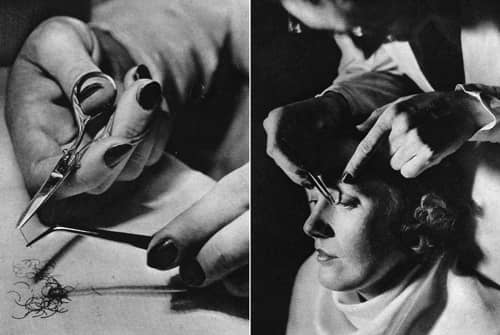

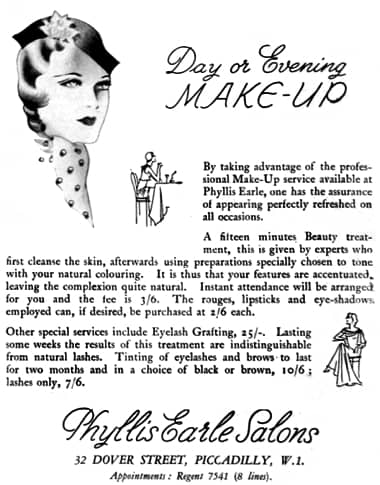

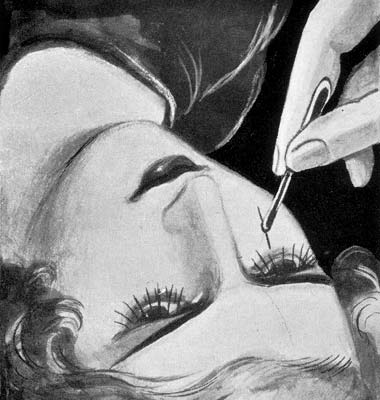

As well as applying strip lashes, some salons in the 1930s offered a service that stuck individual false hairs on to the client’s own lashes, a process often referred to as eyelash grafting. Exactly who came up with the idea is an open question. As well as the Madame Antoine mentioned below, George Westmore [1879-1931] also laid claim to having invented the technique. In all likelihood more than one person thought of it.

The fixing of the lashes, one by one, by means of a special adhesive, takes a good hour, and it requires a steadiness of hand and keenness of eyesight on the part of the operator which is the result of long training. It was Madame Antonie, I believe, who first launched the system of fixing the lashes one by one, and this method of attaining the beauty of expression of a Greta Garbo or a Marlène Dietrich—that velvety or mysterious look of the eyes that every pretty woman likes to possess—has entirely superseded the old system among those who can afford to pay the price.

(The Hairdresser and Beauty Trade, 1933)

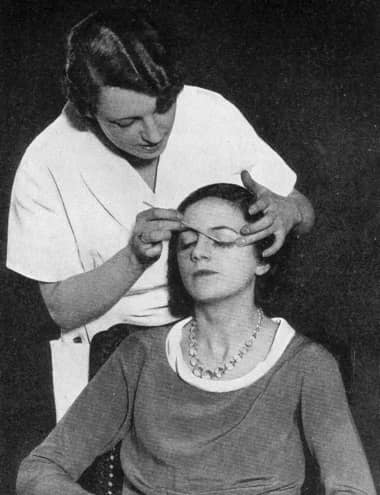

The procedure required a great deal of expertise so was normally only carried out in a beauty salon.

Above: 1932 Grafting false eyelashes. Left: Selecting eyelashes to suit the client. Right: Fastening the eyelashes to the client’s lashes.

Above: 1932 The completed eyelashes after the procedure.

The outfit for grafting eyelashes consists of a small tube of special gum, a packet of lashes, ready curled, a small round china container, a pair of long tweezers, an eyelash brush, and a pair of cuticle scissors.

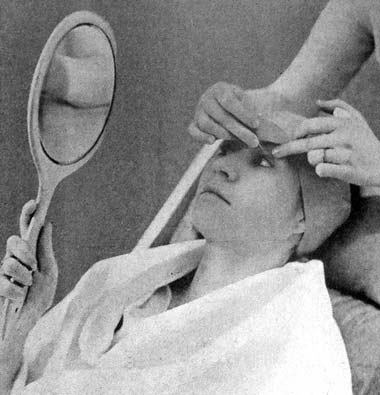

Lift your client’s chair slightly back so that you do not have to strain over the top of her head, but at the same time you do not want her as far back as for a face treatment. Give her a hand mirror, in which to watch the process. By so doing, you enable her to keep her eyes steady, and prevent her from constantly blinking her eyes. And also you are making the operation more interesting for her. Before applying the lashes, make sure that the eyelid and real lashes are free from any trace of grease or mascara. The safest way to do this is to firmly sponge the closed eyes with a piece of soft muslin, and brush the lashes apart with your eyebrow brush.

Place two or three drops of the gum into your container, which you then place in the hollow of the thumb of your left hand. Sprinkle a dozen or so of the lashes over the back of this hand, and then with your finger slightly lift the eyelid from the eyebrow.

Hold the tweezers in your right hand and pick up one of the lashes. Try to hold it so that only one-quarter of the hair is held in the tweezer. Now dip the lash into the gum, so that half of it is sticky. Now carefully lay this lash along one of the real ones, so that it actually rests on it. I advise you to start with the left eye, and work from the outer corner to the nose.

To begin with, make a framework of about sixteen for either eye, and then cut them. To do this, use your cuticle scissors with the points outwards. The eyes should, of course, be shut for this proceeding.

Cut each hair separately, and so prevent a clubbed appearance.

Now add more lashes, until they are thick enough.

In the case of gaps it is sometimes necessary to lay your lashes slightly across the real ones and so build them up. Be sure you apply them thickly enough, and also that you cut them to a reasonable length. If you do not watch this point, they are apt to look like spider’s legs.

The artificial eyelash should not touch the eyelid, it should be a fraction of an inch away from it. When you have finished, go in front of your client and look up at the eyelashes. This is to ensure that you have left no gaps.

Cut the lashes to suit your client’s eye, but always make them shorter towards the nose.

Properly performed, the method of application should be undetectable even at close quarters. To attain this perfection, you need a great deal of practice, an infinite amount of patience, and a steady hand.

The first point to master is the picking up of the hairs so that they are at the correct angle to apply. This is purely a matter of practice. The actual placing-on of the lashes is where your patience is necessary.(Eaton, 1936)

The treatment was more expensive than strip lashes but many beauty specialists considered it more effective; it was certainly more lucrative.

You can introduce this treatment in two ways. First as an application at a fixed cost, and any consequent repair charge according to the time taken. Secondly, you can charge an inclusive fee for the application, and six consecutive weekly repairs. I do not advise anyone to keep on the lashes for longer than six weeks before they are completely removed and fresh ones applied.

(Eaton, 1936)

Although eyelash grafting avoided the lifting or falling off problems associated with strip lashes, getting the curl right was still an issue as there was very little variation in the false eyelashes made at the time.

The strips with the eyelash affixed are not comfortable on the eyelid, but some people still prefer them to the newer method of eyelash grafting. Each lash is grafted with gum on to the existing lash, and except for feeling a little heavy, there is no sense of discomfort. The lashes are really too long when applied, and have to be trimmed to a suitable length, but the main drawback here is that the curl is also cut away, leaving the eyelash standing out rather straight, which does not look, especially from the sideview, exactly artistic.

(The Hairdresser and Beauty Trade, 1937)

Postwar period

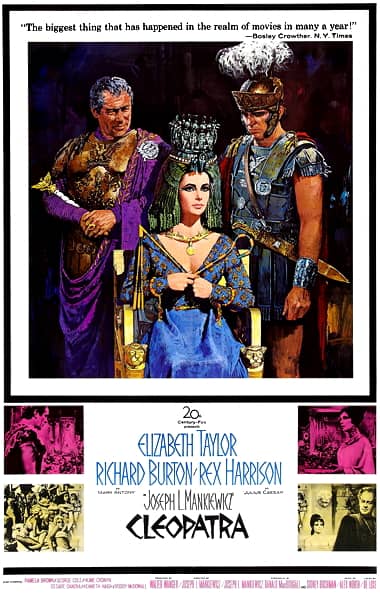

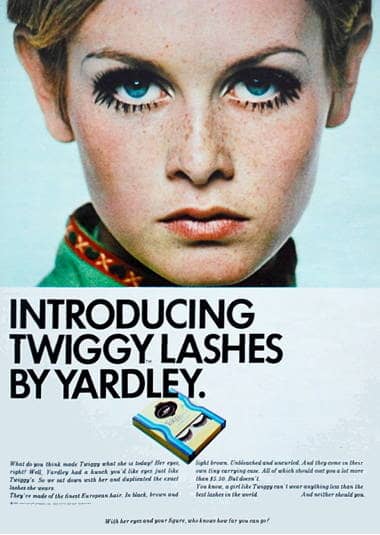

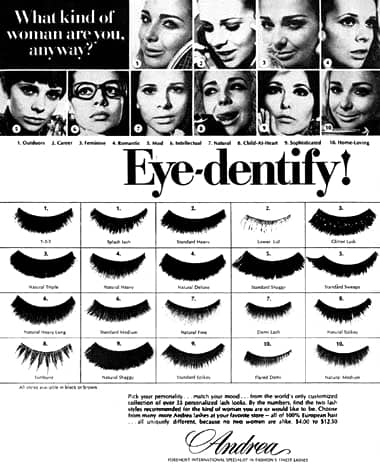

After the Second World War there was a shift away from deep red lipsticks to paler pinks. These lighter lipstick colours reduced the prominence of the lips and helped to shift the central focus of face from the mouth to the eyes. In the 1960s, this trend culminated in the European look of big eyes in a pale face epitomised by models like Jean Shrimpton [b.1942] and Lesley Hornby (Twiggy) [b.1949] which increased the demand for false eyelashes. The 1963 release of the film ‘Cleopatra’ also stimulated sales.

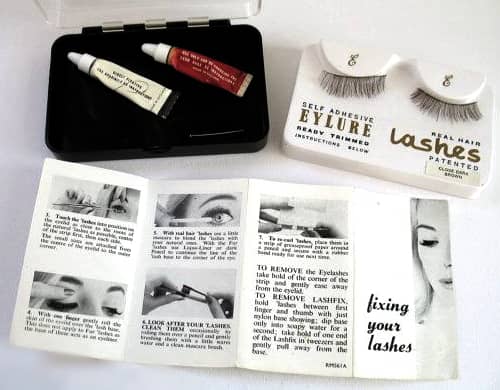

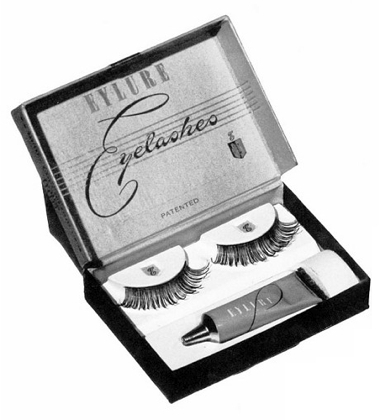

A number of companies took advantage of this trend but only a few cosmetic companies actually manufactured false eyelashes. The most important of these was Eylure, founded in 1947 by David Aylott [1914-1991] and his brother Eric Aylott [1917-2010], both make-up artists working the in the British film industry.

Eylure lashes were made using a method very similar to those manufactured by Ey-Teb but used nylon as the base filament which was a good deal sturdier than cotton, linen or silk. The Aylotts would have seen Ey-Teb eyelashes during their film work in Britain in the 1930s as some actresses would have used them. Ey-Teb had opened a salon at 4 Hanover Street, London in 1936, and also advertised in ‘The Stage’, a leading British trade newspaper.

The first lashes manufactured by Eylure were made from human hair. These were flexible and could be curled before or after they were applied. In 1962, Eylure introduced fur lashes made from seal skin, often labelled as mink. They were heavier and hotter to wear so were generally restricted to cold climates or used for evening wear.

Above: Seal skin and some different types of Eylure fur lashes made using it. Most ‘mink’ lashes sold in the 1960s were actually made from seal skin. Fur lashes were heavy so it was generally suggested that it was best not to weigh them down even further with mascara.

See also: Eylure

The swinging sixties

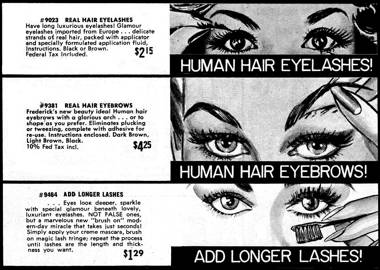

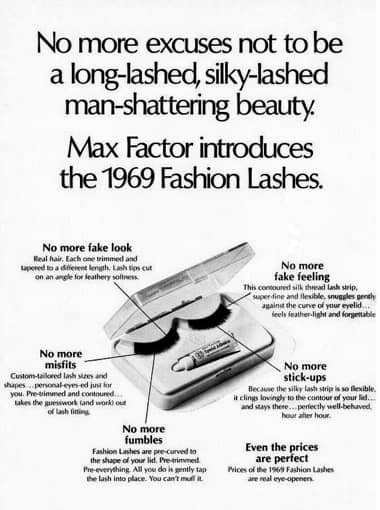

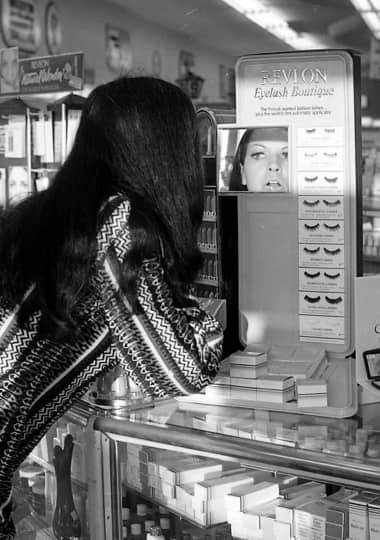

The 1960s were a highpoint for false eyelashes in the twentieth century. By 1968, American sales of false eyelashes had jumped to more than 20,000,000 pairs a year (Australian Women’s Weekly, 1968) and were being sold by a large number cosmetic manufacturers including Elizabeth Arden, Helena Rubinstein, Revlon, Yardley, Seventeen, Lenthéric and Max Factor. Most of these lashes were made by Eylure either in Britain, Belgium or Malta.

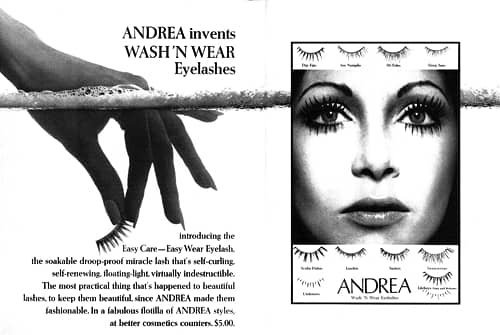

In the United States, Andrea lashes from the Andrea Mass Company, founded in 1964, were also experiencing good sales. The company had originally sold eyelashes under the Eye-Lusion brand but switch to calling them Andrea after they were challenged by Eylure. Andrea Raab sourced its lashes from South Korea which manufactured them very cheaply. Eylure would follow and soon the majority of the world’s false eyelashes were being made in places like South Korea or India where labour was cheaper.

False eyelashes of the period were produced in a wide range of lengths, thicknesses, styles and colours (not just blacks and browns). Eylure, for example, made over 30 different styles ranging from more natural lashes made from real hair or fur, to forms with added paste jewellery for evening wear. Women could apply them at home, have them added at their local beauty salon, or go to one of the many specialist Lash Bars that sprang up at the time.

Using false eyelashes was not without its problems. Eye problems could be created from occasional allergic reaction to the glue. In addition, women who repeatedly reused their false eyelashes ran the risk of the glue and other material building up along the base of the lashes. The glue could be removed by soaking the strip lashes in white spirits, dry cleaning fluid or some other solvent to soften the gum, which was then gently eased off, but many companies introduced lash cleaning kits to help with this problem.

The lashes could also create eye problems through accumulating dirt and other material. The use of synthetic materials such as wash-and-wear eyelashes introduced by many companies helped alleviate this problem.

Above: 1971 Andrea Wash ’N Wear Eyelashes.

Applying false eyelashes

Strip lashes were used in single, double or triple rows depending on the desired effect and placed on the eyelid with a pair of tweezers or with an eyelash applicator.

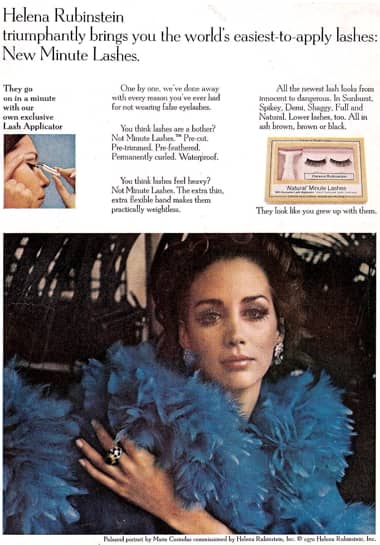

Above: 1970 Helena Rubinstein Minute Lashes with applicator.

The lashes were glued to the upper eyelid – using surgical adhesive, eyelash adhesive or some other gum – but some women also fixed them on the lower lids as well – a new development for the time.

Above: Eylure kit with self-adhesive false eyelashes, with two types of Lashfix adhesive (red for recharging the base, white for instant fix), and instructions.

Also see the Eylure booklet: Fixing your Eyelashes. (c.1963)

Stretch your eyelid with one hand, and with the other place the centre of the false lash base at the centre of your own lash-line. Then smooth into position to the corners. Never use too much adhesive.

The trick is to spread a little adhesive on a piece of paper. Then holding the lashes with tweezers, press the base on to the adhesive. Do NOT place false lashes too close to the inner corner of the eye.

False lashes usually look best if you use only three-quarters or half so they give a fringing to the outer edge of the eye.(Daily Mirror, Monday, February 6, 1967, p. 9)

Most lashes are sold in a standard length and width. They are shaped by placing them on a flat surface and cutting the individual hairs with cuticle scissors, unevenly, and at an angle to avoid an obvious blunt end.

Likewise, lashes should not be blunt and square at the outer corner of the eye, but rather slightly longer and tapered – similar to your own – for a natural effect.

Make sure your lashes fit your lid. Snip off any excess.

The only necessary tools are:

1. Mirror – always below eye-level so you are looking down.

2. Tube of adhesive – surgical adhesive is the cheapest and best.

To apply, hold lashes firmly between two fingers (or tweezers) and spread adhesive in a thin line, with a toothpick, along the lash base. Wait a moment, then apply to lid.

Starting about a quarter of an inch from the inner corner of the eye, hold directly in front of your eye and affix directly above the roots of your own lashes.

That is all there is to it. The entire application takes less than two minutes.(Australian Women’s Weekly, 1968)

Also see the Max Factor booklet: Geminesse Lash Creations (c.1970)

Some women cut their strip lashes into segments so that they could apply them in groups. This was quicker than applying individual lashes while still giving them a more natural look.

Using a cuticle clipper, separate the false lashes into small tufts of two to three lashes and place them on a tissue. If they are of the same length, they should be cut to different lengths to give them as natural an appearance as possible. They must be longer near the outer portion of the eye and shorter towards the inside. Place some glue on your hand, and using a pair of tweezers, pick up the lashes and dip the base of the lashes in the glue until they are well soaked. Place the false eyelashes at the base of the natural eyelashes. Pick up another tuft and continue in the same way for the rest of the upper and lower lids. Single false eyelashes can be kept in place for several days as long as the eyes are cleansed with a special lotion and not with ordinary oil.

(Tremblay, 1978, pp. 196-197)

This innovation was picked up by manufacturers who began to retail boxes of false hairs grouped into clusters – another new development for the time.

Decline

As with many fashions, the use of false eyelashes went to extremes in the 1960s – with types made with feathers, faux gold or silver, or encrusted with paste jewellery – and then faded. As the fashion trends moved towards a more ‘natural’ look in the 1970s, eyes and eyelashes continued to retain their importance but many woman switched to easier to use lash-extending mascaras. Many women continued to use them as they have slipped in and out of fashion in the subsequent decades.

Updated: 4th September 2018

Sources

The Australian women’s weekly. Sydney, Australia: Author.

Corson, R. (1972). Fashions in makeup: From ancient to modern times. London: Peter Owen.

Corson, R., & Glavan, J. (2001). Stage makeup (9th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Eaton, D. A. (1936). Applying false eyelashes. Beauty Culture. 7(20), 10.

Gerson, J. (1992). Milady’s standard textbook for professional estheticians (7th ed.). Milady Publishing Company.

Goodman, S. (1958). Eyelashes. Drug and Cosmetic Industry. 82(6), 734-735, 813-816.

The hairdresser and toilet requisites gazette. London, England.

McLaughlin, T. (1972). The gilded lily. London: Cassell & Co. Ltd.

Tremblay, S. (1978). The professional skin care manual. London: Prentice-Hall.

Verni, M. (1946). Modern beauty culture (2nd ed.). London: New Era Publishing.

1882 Fringed eyelashes being sewed on to brighten eyes (McLaughlin, 1972) The wigs in the background points to this being a hairdresser/wigmaker.

Karl ‘Charles’ Nessler [1872-1951], the originator of the ‘Permanent Wave’. He also went under the name of Charles Nestlé.

1902 Drawings from Charles Nessler’s patent for making artificial eyelashes and eyebrows.

1911 Drawings from Anna Taylor’s patent for making artificial eyelashes (US: 994,619).

1911 C. Nestlé & Co., founded in London by Charles Nessler.

Fish bladders were used to make isinglass or ‘fish-skin’.

1929 Greta Garbo [1905-1990]. Her natural lashes were widely emulated.

Nestolashes from the Nestlé-Le Mur company set up by Charles Nessler in New York.

Nestolashes No. 1 for street wear. They came in Blonde, Brown, Dark Brown and Black shades. Nestolashes No. 2 were for stage and screen and only came in Black.

“Directions for Eyelashes

To apply: Spread a very thin film of Nestoline on foundation with a stick. Wait about one-half minute to allow Nestoline to dry a little and press against your own lid directly above your own lashes.

To Remove: Catch he foundation with your fingernail and lift away. do not pull by the hairs.

To Cleanse: Dampen foundation with water and rub very gently with fingers.”

Drawings from the patent taken out by Marjorie A. Birk (US1,897,747, 1933).

1932 Phyllis Earle Eyelash Grafting service. “Lasting some weeks the results of this treatment are indistinguishable from natural lashes.”

1935 Myrna Loy wearing a set of highly curled, very long, false eyelashes. They have probably been crimped with a Kurlash eyelash curler.

1935 Fitting false eyelashes in a beauty salon.

1936 Grafting eyelashes. Artificial eyelashes were glued to the client’s real lashes not to the lid.

1937 Ey-Teb salon New York.

1937 Prima-Derma. This French advertisement appears to be for eyelash grafting.

1946 False eyelashes (Verni, 1946). These appear to be individual lashes attached to the eyelid.

1946 Applying single lashes (Verni, 1946).

A set of false eyelashes made by Eylure Cosmetics. This English company began selling false eyelashes in 1947 before going on to make eyelashes for a number of other cosmetic companies.

1958 A LIFE magazine article describing cheap plastic eyelashes attached to a transparent strip tinted to resemble eyeshadow. They could be taken off each night and washed in soap and water. Notice that in each case the eyebrows have been darkened and eyeliner and mascara has also been used to increase the effect.

1963 Cleopatra (Twentieth Century-Fox). The film generated an increased interest in eye make-up including false eyelashes worldwide.

1964 False eyelashes and eyebrows by Fredericks.

1967 Lashes by Yardley. The lower lashes were painted on, a technique Twiggy used before she became a model.

Woman with upper and lower false eyelashes.

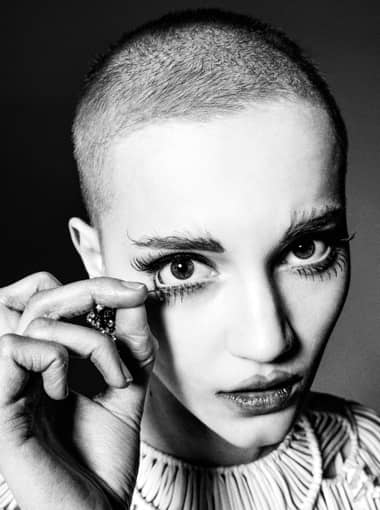

1968 Maybelline.

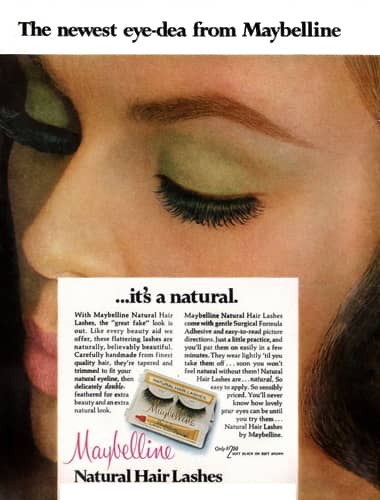

1969 Fashion Lashes by Max Factor.

1969 Petal-like lashes, hand made by Eylure using artificial flower petals intermingled with real hair. Each eye required two pairs, one for above and one for underneath, at a cost of over US$12 per pair.

1969 Andrea Eye-Dentify.

1970 Helena Rubinstein Minute Lashes.

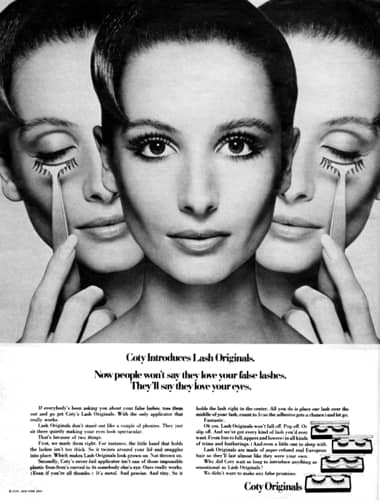

1970 Coty Originals with applicator.

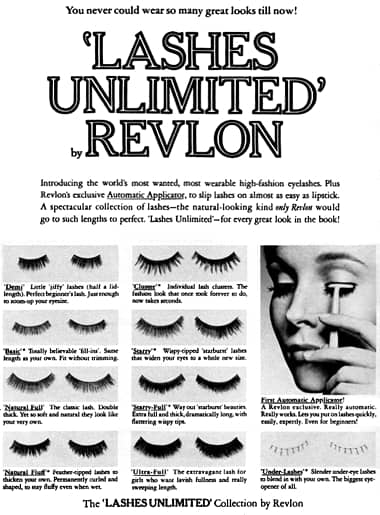

1970 Revlon Lashes Unlimited with applicator.

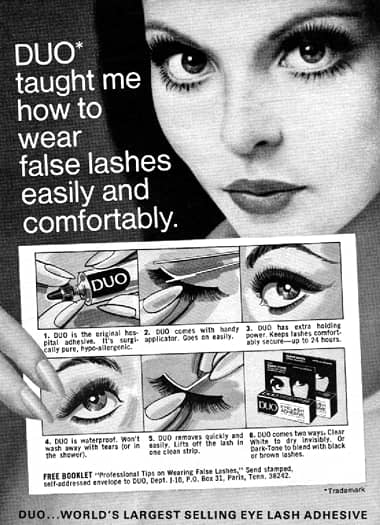

1971 Duo Eyelash Adhesive.

Revlon Eyelash Boutique.