Iontophoresis

Iontophoresis is an electrical treatment used to help move substances across the skin or other body surfaces such as the eye. Although the effect was first noted in the eighteenth century, its use in medical treatments only began in earnest in the 1890s.

[W]hile the constant current has proved so very useful to the medical profession for diagnosis, for stimulating nerve and muscle, for electrical endoscopy, and for cauterization, we must not neglect its cataphoretic property, by which remedial agents are diffused through the tissues and fluids of the body to improve nutrition, to produce anaesthesia, to relieve pain, to destroy germs, to modify morbid processes, and to make soluble chemical combinations with deleterious substances which quite frequently collect in the organism.

(Peterson, 1895, C-19)

Notable practitioners include Benjamin Ward Richardson [1828-1896], Hermann Munk [1839-1912], William James Morton [1846-1920] and Stéphane Leduc [1853-1939].

Basic principles

Iontophoresis works on ions – water-soluble substances that have either a positive or negative charge – and is based on the general principle that like charges repel and unlike charges attract. By using a direct (galvanic) current, ions can be ‘pushed’ into the skin if the electrode (the active or working electrode) being used has the same charge as the ions in question; i.e., positive ions (cations) will be pushed into the skin by the positive electrode (anode) and negative ions (anions) will be similarly affected by the negative electrode (cathode).

See also: Galvanic Treatments

It is very difficult to move water-soluble chemicals across the skin’s surface, so when it was first introduced the medical profession hoped that iontophoresis would be able to deliver drugs across the skin without using needles. Unfortunately, due to a variety of factors – including the excellent barrier properties of the skin – this has not held up in practice and iontophoresis currently has limited medical applications, such as treatments for hyperhidrosis (abnormal sweating of the palms or other areas of the body).

Cataphoresis

Early mentions of the technique refer to the process by a variety of names including electric osmosis, electro-chemical osmosis, ionic medication and cataphoresis, the latter coming from the fact that the liquid is carried down (cata, down; pherein, to bear). These were general terms applied when either the positive (anode) or the negative (cathode) electrode was used.

Over time the medical profession began to distinguish between procedures that used different working electrodes. The term cataphoresis then became restricted to treatments where the positive electrode was the working electrode (it pushes cations) and a new term, anaphoresis, began to be employed for those that used the negative electrode (it pushes anions). As this distinction took hold, both process were sometimes referred to as phoresis but over time this term gave way to iontophoresis, a term first used by Dr. Fritz Frankenhäser [b. 1868] sometime before 1908.

The earliest record I have for a salon practice being called iontophoresis is by Helena Rubinstein in 1935 but beauty experts continued to call it phoresis or cataphoresis (as the term was originally coined) for many years after that.

Iontophoresis in Beauty Culture

Using electricity to increase the penetration of chemicals into the skin was quickly adopted by Beauty Culture. Ruth D. Maurer [1871-1945], who began Marinello, makes mention of the principle in the book she almost certainly wrote in 1903.

Experiments have proved that by moistening electrodes with certain substances and applying them to the unbroken skin, making the current sufficiently strong, the materials have been forced into circulation. For instance, concentrated solutions of sulphate of quinine and iodide of potassium can be detected in the urine thirty minutes after they have been applied to the skin. The amount detected after four or five hours is even greater, showing that the process has been going on steadily. In all of this work the idea is, of course, to cause the drugs to enter the circulation.

(McIntosh Battery and Optical Company, 1903, p. 140)

Like other beauty experts of her time, Maurer – writing under her pseudonym, Emily Lloyd – referred to the practice as cataphoresis rather than phoresis or iontophoresis.

In some instances and by a few authorities the general process is known by the term “phoresis.” When the positive electrode is employed, it is called the “anophoresis,” [sic] and when the negative is used it is called cataphoresis. As this method is somewhat confusing to the student, we shall throughout refer to the process as cataphoresis no matter which electrode is employed.

(Lloyd, 1914, p. 125)

Maurer’s first use of cataphoresis, as she called it, was to help in bleaching the skin a practice she may have picked up from dentistry where cataphoresis was combined with pyrozone (hydrogen peroxide) to bleach stained teeth.

Above: 1907 Marinello bleach treatment using Antiseptic Lotion – a proprietary Marinello line containing hydrogen peroxide – applied with a negative carbon electrode.

Initially enthusiastic, Maurer later dissuaded Marinello practitioners from using cataphoresis during regular skin bleaches and suggested restricting its use to situations where the discolouration was very deep, such as in chloasma.

After the paste has become thoroughly dry it may be removed by washing the skin with luke-warm water, and then if the patches on the face or neck are very deep, the bleaching lotion may be forced into the skin by means of the negative electrode, … continuing the process until the skin is thoroughly reddened. This process, it should be understood, is only used for moth patch or chloasma, and would not be used in the ordinary treatment at all.

(Lloyd, 1907, pp. 89-90)

Maurer also described how cataphoresis could be used to administer a local anaesthetic – a mixture of cocaine and adrenalin – to relieve pain during electrolysis, another technique she may have picked up from dentistry.

Owing to the danger of infection, no one cares to administer cocaine by means of the hypodermic needle and to place this solution upon the skin alone will have absolutely no effect, unless it can be used on the mucous membrane.

It may, however, be successfully forced into the tissues by means of the positive electrode and thus the portion treated without any sensation whatever.(Lloyd, 1914, p. 126)

Solutions containing sulphur compounds, applied with the positive electrode, were also widely employed in early Beauty Culture to treat acne-prone skin or seborrhoea. Solutions of alum, zinc and other substances commonly found in astringent and toning lotions were sometimes applied using a positive electrode while alkaline compounds found in cleansing lotions could be used with the negative electrode.

Current treatments

Iontophoretic solutions used in salons today are made with a wide variety of ingredients including vitamins, minerals, collagen, elastin, amino acids, hyaluronic acid and a range of animal and plant extracts. These come in a range of prepared packages including gels, serums and ampoules. Therapists are usually provided with very little information on how these work, other than the skin condition for which they apply and the polarity of the electrode to be used.

As with many ingredients in skin creams, it is doubtful whether some of these substances could penetrate the skin – whether or not an electric current is used – let alone whether they would be effective.

Above: 1963 French acne treatment for the face and chest using iontophoresis. The face and pectoral masks are lined with spongy electrodes soaked with vitamin B6.

Iontophoresis is often used in conjunction with desincrustation, a treatment first introduced into beauty salons in the 1930s.

See also: Desincrustation

Working electrodes come in a variety of forms including balls, rollers, disks and full face masks. As a direct current is used, another electrode – the passive, indifferent or return electrode – is required to complete the electrical circuit and get the current to flow. This electrode can be a bar given to the client to hold, or a pad placed somewhere where it makes good body contact, e.g., under the shoulder or wrapped around the upper arm. Current placement of the return electrode appears to differ from the earliest application of this procedure. Initially, both the working and return electrodes – covered with saturated cotton wool – were applied to the face.

Current claims for iontophoretic treatments include hydration, repair and regeneration of mature or damaged skin, stimulation of sluggish circulation and, in the case of body treatments, the softening and absorption of fat and cellulite. Many of these claims are suspect, given that they rely on the transfer and action of specific ingredients deep into skin tissue.

Updated: 6th January 2020

Sources

Cressy, S. (2004). Beauty therapy fact file (4th ed.). Oxford: Heinemann Educational Publishers.

Gallant, A. (1980). Principles and techniques for the beauty specialist (2nd ed.). Cheltenham: Stanley Thornes.

Kovács, R. (1949). A manual of physical therapy (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

Lloyd, E. (1907). The skin. Its care and treatment (3rd. ed.). Chicago: McIntosh Battery and Optical Company.

Lloyd, E. (1914). The skin. Its care and treatment (5th ed.). Chicago: McIntosh Battery and Optical Company.

McIntosh Battery and Optical Company. (1903). The skin. Its care and treatment. Chicago: Author.

Peterson, F. (1889). Electrical cataphoresis as a therapeutic measure. New York Medical Journal. April 27, 449-453.

Peterson, F. (1895). Cataphoresis, anodal diffusion, electrical osmosis, or voltaic narcotism. In W. J. Herdman, H. McClure, J. M. Bleyer, W. F. Robinson, A. W. Duff, G. J. Engelmann, et al. International textbook of medical electro-physics and galvanism for the use of medical students and practitioners (pp. C1-C20). Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis Company.

Simmons, J. V. (1989). Science and the beauty business. Volume 2. The beauty salon and its equipment. London: Macmillan.

Wall, F. E. (1946). The principles and practice of beauty culture (2nd ed.). New York: Keystone Publications.

The French physician Stéphane Armand Nicolas Leduc [1853-1939]. His papers on the subject helped establish ‘ionic medication’ as a recognised medical treatment.

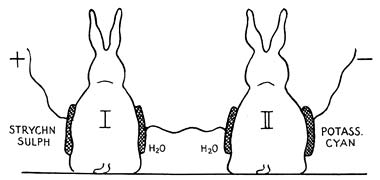

Leduc’s classic experiment showing that electricity was responsible for moving substances into the skin. Two rabbits were connected together in the same galvanic circuit. The first rabbit was connected to the positive pole by a pad soaked in strychnine sulphate while the second rabbit was connected to the negative pole by a pad soaked in potassium cyanide. When the current was connected the first rabbit went into tetanic convulsions due to the strychnine pushed into it by the positive electrode while the second rabbit was poisoned by the cyanide pushed into it by the negative electrode.

If the current was reversed neither rabbit was harmed as strychnine is attracted to, not repelled by, the negative electrode and cyanide is attracted to, not repelled by, the positive one. In this way Leduc demonstrated that it was the electric current that delivered the lethal ions.

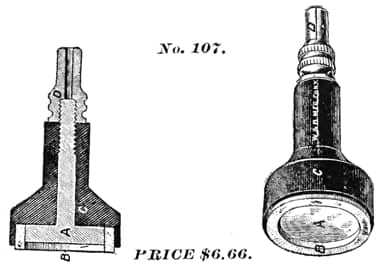

1895 Peterson’s Improved Cataphoric Electrode as advertised by the Waite & Barlett Manufacturing Company, New York.

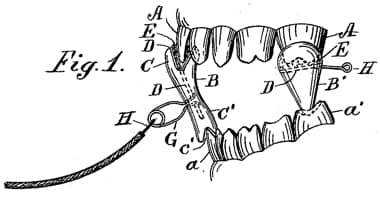

Dentists also experimented with cataphoresis using it to administer local anaesthetics during dental operations – Benjamin Ward Richardson [1828-1896] being an early exponent – and to bleach teeth. This diagram is from a patent for a dental electrode used to “facilitate the diffusion of cocaine and analogous local anesthetics through the bony substance of a tooth to render it insensible during dental operations, the invention thus being an adaptation of cataphoresis to the teeth” (US patent: 592,878, 1897).

1903 Cataphoresis treatment in a Marinello salon. The positive and negative electrodes are both placed on the face.

1923 Marinello cataphoretic treatment using a ball electrode to administer Methine – a proprietary compound produced by Marinello, later called Methene – to treat acne rosacea.

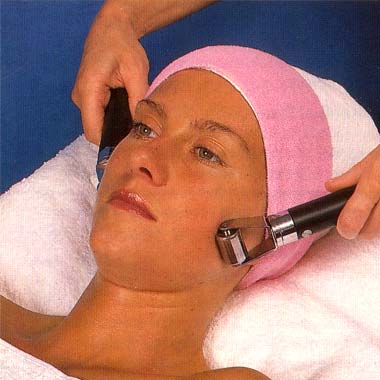

The original Guinot Cathiodermie machine developed in 1965. The therapist is using roller electrodes and the client looks to have the return electrode attached to her wrist. The man in the photograph appears to be René Guinot.

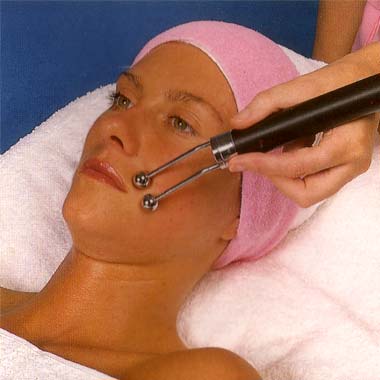

Roller and Ball electrodes used in Guinot’s Cathiodermie treatment which iincluded desincrustation. “First of all make-up and superficial oiliness are removed (Lotion Speciale) while a small amount of solution (Electro Z) helps the skin conduct the minute galvanic current. Then a gel (Hydragel) which deep cleanses, feeds and corrects moisture balance, is selected for your skin type and applied. The gel is ionised, so that the galvanic current used in this part of the treatment can attract it like a magnet into the pores where it gets to work dissolving impurities. Now the next effect of the galvanic current comes into action. By stimulating the circulation it produces a light perspiration which returns the gel, now combined with waste matter, such as ingrained make-up, dirt and stale sebum back to the surface of the skin to be removed by the beauty therapist. At the same time, the spots and blackheads also loosened by the process are carefully extracted.” (Taken from an undated Guinot brochure)

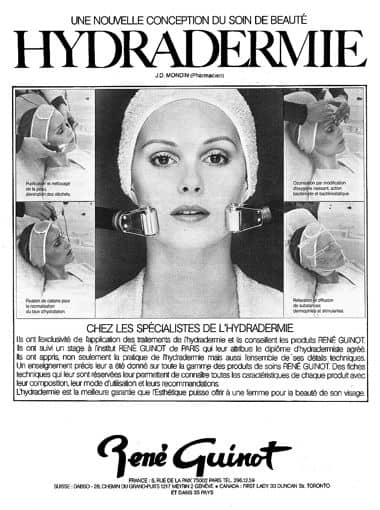

1980 René Guinot Hydradermie. Jean-Daniel Mondin took over Guinot in 1972 and the original Cathiodermie treatment was modified and renamed.