Atkinsons

Continue to: Atkinsons (post 1930)

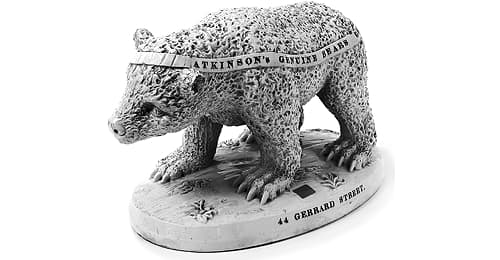

Most stories describing the origins of Atkinsons connect its founder, James Atkinson [1782-1853], with Cumberland, a bear, bear’s grease, and a shop on Gerrard Street. This example from ‘The Chemist and Druggist’ marking the sesquicentenary of the firm is typical:

James Atkinson, the founder, though he became with little doubt the leading perfumer of Regency London, was a Cumberland man. His only resources when he set out on foot to conquer the metropolis were a supply of animal fat and a bear. Under the designation “bear’s grease” the fat, perfumed with otto of rose, was sold as a pomade for the hair. It found a ready market among the smart set of the time.

On arrival in London Atkinson established himself in Gerrard Street, Soho. By chaining the bear outside his premises he attracted that amount of notice which today is only as a rule achieved by an extensive and necessarily costly Press advertising campaign.(From bear’s grease to lightheart, 1949, p. 286)

Unfortunately, available records fail to confirm this traditional founding story.

Tradition has it that James Atkinson started his business at 44 Gerrard Street in 1799, the same year Napoleon Bonaparte [1769-1821] seized power in France, when James would have been about 17 or 18. Unfortunately, the business does not appear in the 1806 edition of Kent’s Directory of London Merchants and Traders nor is it in the 1807 or 1808 editions of the London Post Office Directory. This may be because he did not start his business in 1799, or it was begun outside London, was commenced under another name, or was trading without a fixed address. The first record I have for James Atkinson is dated 1811, when he was located at 9 High Street, Bloomsbury. He only moved to 43 Gerrard Street, Soho in 1813, and did not relocate or expand next door to 44 Gerrard Street until 1818.

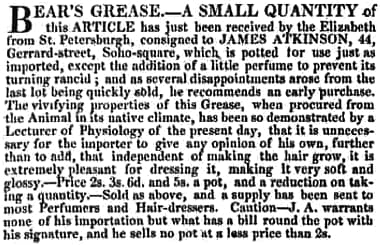

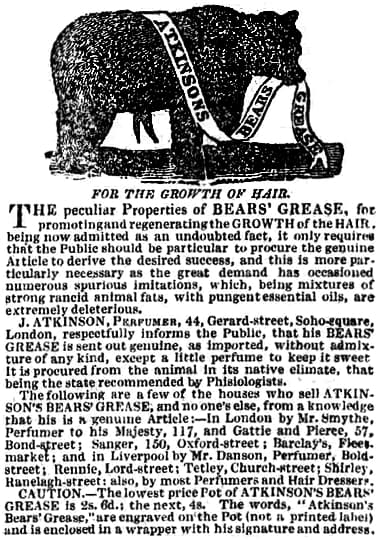

Regarding the bear and the bear’s grease, it is possible that, at some stage, Atkinson had a bear chained up outside his shop to advertise that he had bear’s grease in stock, but he does not seem to have been selling bear’s grease until the 1820s. This makes it very improbable that he started out from Cumberland with a bear on a chain.

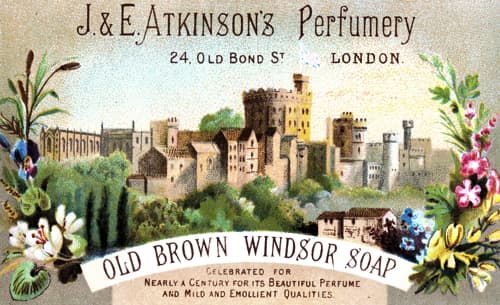

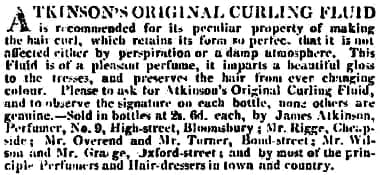

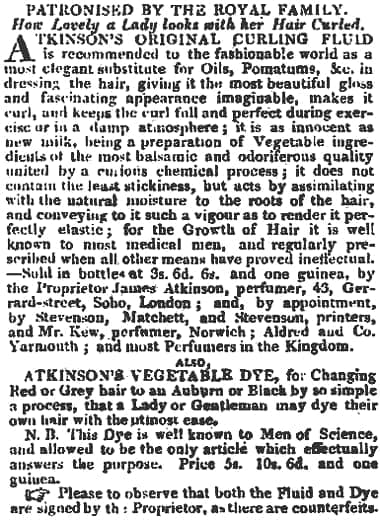

Rather than bear’s grease, the first record I have of a product James Atkinson advertised for sale is for Atkinson’s Original Curling Fluid (1811) which, as its name suggests, was a hair curler. The first advertised dates for other early Atkinson products that I have are: Atkinson’s Vegetable Dye (1812), Atkinson’s Ambrosial Soap (1815), Atkinson’s Lavender Water (1816), Atkinson’s Windsor Soap (1822), and Atkinson’s Concentrated Essence of Lavender (1823). We do not arrive at advertisements for Atkinson’s Bear’s Grease perfumed with Otto of Roses until 1824.

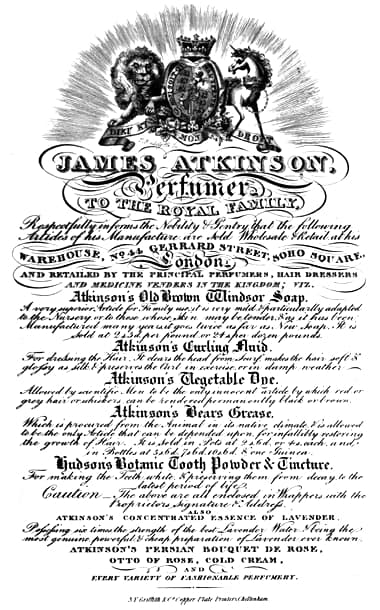

Once established, Atkinson’s business expanded. In 1826, James Atkinson was appointed perfumer to the royal family, the first of many royal warrants. In 1828, he opened a retail establishment at 39 New Bond Street, keeping 44 Gerrard Street for his wholesale customers. Anyone visiting the shop in New Bond Street would see a wide variety of articles for sale. As well as Atkinson’s own range, there were products on display from suppliers such as Hudsons, Rowlands, Houbigant and Farina.

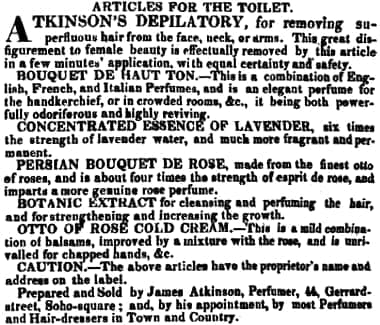

Atkinson fragrances sold at this time included Concentrated Essence of Lavender, Otto of Rose, Persian Bouquet de Rose, Eau de Portugal, and Bouquet de Haut Ton. He was also selling a number of cosmetics: Atkinson’s Depilatory (1826); Otto of Rose Cold Cream (1826); Cream of Roses (1829), another cold cream; and Milk of Almonds (1830). The dates listed are the earliest advertised that I have sourced.

Atkinson’s Depilatory: “[F]or removing superfluous hair from the face, neck or arms. This great disfigurement to female beauty is effectively removed by this article in a few minutes’ application, with equal certainly and safety.”

Otto of Rose Cold Cream: “This is a mild combination of balsams, improved by a mixture with the rose, and is unrivalled for chapped hands, &c. and safety.”

Cream of Roses: “[A] great improvement to what has long been known as Cold Cream. It is more pure, the cheap objectionable ingredients of the latter being omitted, and others of a more expensive emollient and balsamic quality introduced. It also keeps better, and imparts a fine rose perfume. It is particularly recommended to Gentlemen to use a little after shaving, and is an excellent lip salve.”

Milk of Almonds: “It is an emulsion of the finest almonds, peculiarly prepared, concentrating all their balsamic softening and other well known qualities, and is particularly adapted for cooling the skin where chafed from a burning sun, or other heated atmosphere, making it transparently white, soft and even. It also removes freckles, redness, hardness and sunburn, and to gentlemen whose faces are tender from shaving, it gives welcome relief.”

None of these products are particularly significant. Numerous versions of each were produced by other firms before Atkinson’s came on the market.

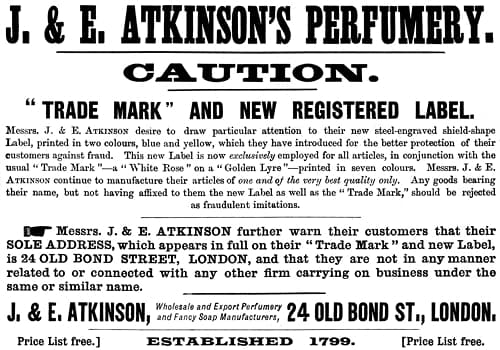

J. & E. Atkinson

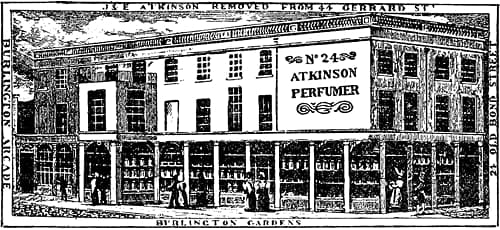

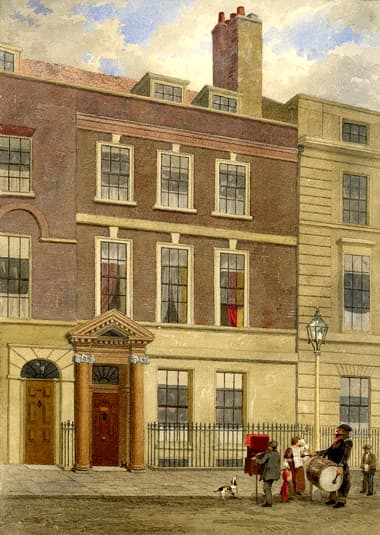

In 1831, James Atkinson’s brother, Edward [1800-1858], was made a partner and the firm was renamed J. & E. Atkinson. Edward appears to have been primarily responsible for expanding Atkinsons into the provinces. In 1832, the continued growth of the firm saw the brothers move the retail and wholesale business to 24 Old Bond Street where it would remain until the 1960s.

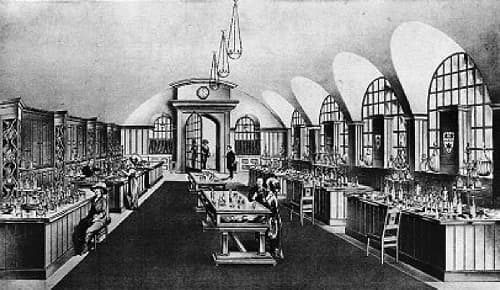

Above: c.1832 J. & E. Atkinson, removed from 44 Gerrard Street to 24 Old Bond Street, London.

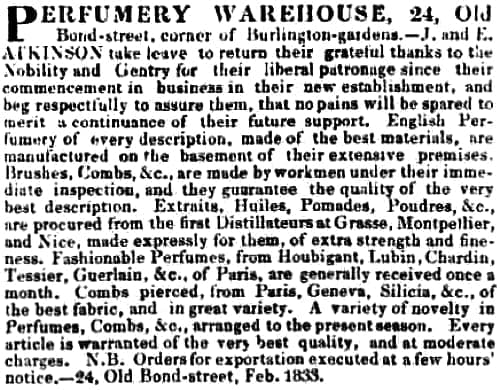

Retail customers coming into the Old Bond Street store in the 1830s could expect to find a wide range of Atkinsons’ perfumes and other products but, as before, would also find wares from French houses such as Houbigant, Lubin, and Guerlain.

Following the death of James Atkinson in 1853 and Edward in 1858, management of the business passed into the hands of Edward Atkinson’s son, James Atkinson. In 1869, he hired Eugene V. Barrett to help him run the business. Barrett is generally credited with expanding the company’s exports.

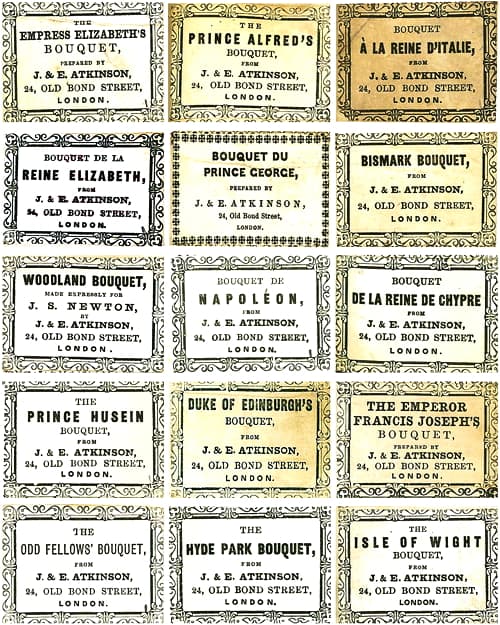

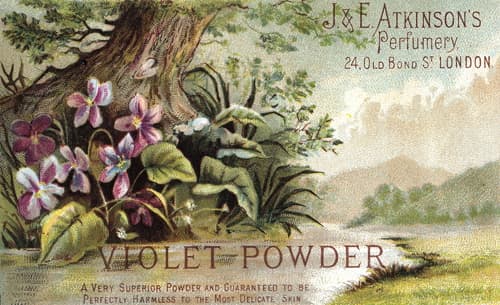

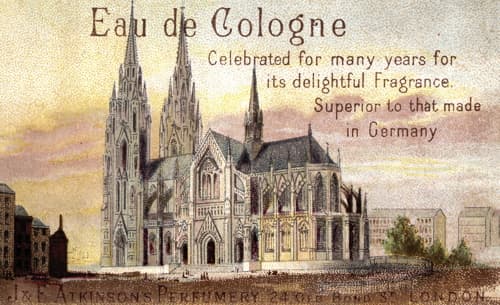

Above: Fragrance labels from J. & E. Atkinson.

When James Atkinson died in 1895, Eugene Barrett was left in charge. In 1896, he incorporated the company, which then became J. & E. Atkinson Ltd. with a capital of £200,000. The following year his son, Horace Barrett, entered the firm, later becoming the company’s managing director.

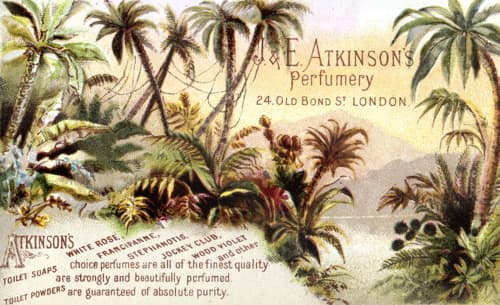

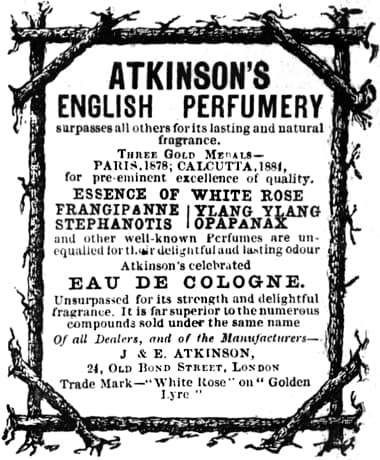

Above: 1888 J. & E. Atkinson’s Perfumery.

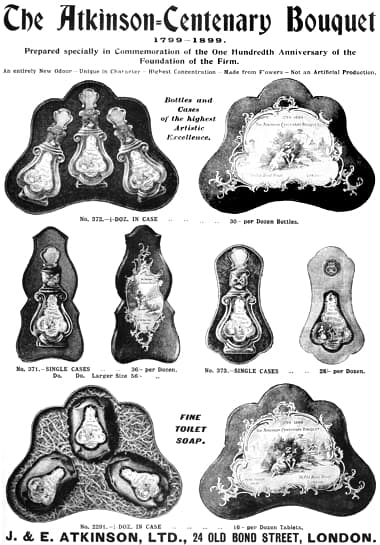

Centenary

In 1899, Atkinsons celebrated its centenary by announcing a new perfume called Centenary Bouquet. By now, the company had established itself as a respected manufacturer of high-class perfumes and soaps, having won a number of medals at trade shows and expositions around the world including London (1862), Paris and Cordova (1867), Lima (1872), Vienna (1873), Melbourne (1875), Philadelphia (1876), Paris (1878), Calcutta (1884), and Paris (1889). Of these, the Gold Medal it received in Paris at the 1878 Exposition Universelle was the most prestigious.

Products

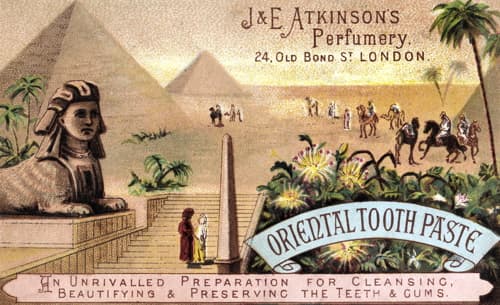

Atkinsons manufactured a wide range of products including perfumes, toilet powders, face powders, skin creams, toilet soaps, hair lotions, depilatories and toothpastes.

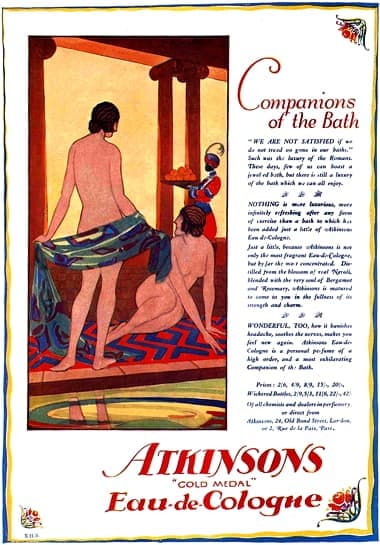

It had also given up importing Farina Eau de Cologne and was making its own, taking out a trademark for Gold Medal Eau de Cologne in 1886.

These products were made in Floral Street in Covent Garden, or at 24 Old Bond Street. The company also shared a bonded factory at St Katherine’s Dock, next to the Tower of London, where perfumes could be made for export using duty-free alcohol. In 1898, Atkinsons also established a showroom at 8 Wood Street, Cheapside to cater for the export trade and domestic wholesale buyers.

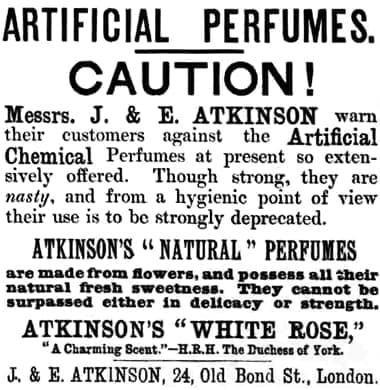

At the turn of the century the Atkinsons’ prospects looked bright but there were some troubles on the horizon. Not only had the French perfume industry fully recovered from the 1870 Franco-Prussian War but some French houses had begun formulating perfumes with synthetics. Nineteenth-century examples of these include Fougère Royale by Houbigant, Jicky by Guerlain, and Vera Violetta by Roger & Gallet. Atkinson warned its customers about these ‘artificial perfumes’ and its new Centenary Bouquet fragrance was advertised as ‘Made from flowers – Not an artificial production’. However, as Coty would dramatically show, synthetics were the future.

See also: Coty

A new century

In 1900, Atkinsons received the Grand Prix at the Exposition Univeral in Paris and the following year received another royal warrant, this time from Edward VII [1841-1910]. However, a fire gutted the building in Floral Street in 1901 destroying a large volume of stores and most of the building. Despite this setback, the business continued to expand in the years leading up to the First World War. To help finance this, the company issued £20,000 in debentures in 1906. More manufacturing space was also needed and, in 1910, Atkinsons consolidated its manufacturing and wholesale business into a single site at Southwark Park Road, Bermondsey, London, named the Eonia Works.

Eonia Works

The entrance to the Eonia Works was graced with building designed by E. Keynes Purchase [b.1862].

Above: 1911 Entrance to the Eonia Works.

This building housed a general office on the ground floor and directors and secretarial offices upstairs.

Above: 1911 Eonia Works: General Office.

Behind this building was the factory itself, divided into two sections, a Free Factory and a Bonded Factory.

The Bonded Factory enabled Atkinsons to make perfumes and other goods for export without paying excise duty and allowed the company to close down their shared operation in the St Katherine’s Dock.

The basement and ground floors of the Bonded Factory were ‘Free’ and used to store materials required in factories and packing floors above. Entrance to the bonded part was through the first floor, which were policed by a Customs and Excise official on the door.

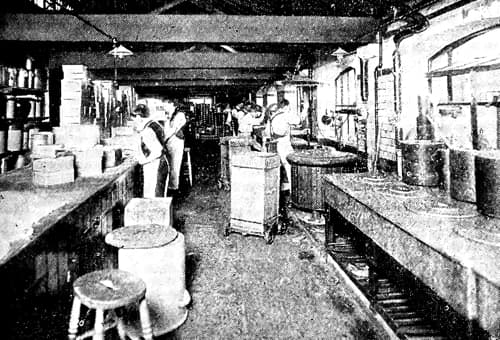

Above: 1911 Eonia Works: Perfumery Floor.

Perfumes, hair lotions, brilliantines and other products that used alcohol were formulated on the third floor then passed down to the second floor for bottling and packaging.

Above: 1911 Eonia Works: Bonded Finishing Room. Perfumes using duty-free alcohol are bottled, capped, labelled and packed in cases.

The top floor of the Free Factory was devoted to the manufacture of soaps, including Old Brown Windsor, and a range of toilet and shaving soaps. The second floor was used for perfumes as well as liquid and cream toilet preparations along with toilet, face, sachet, and other powders.

Above: 1911 Eonia Works: Cream and Cosmetic Department.

The basement stored finished products for the home market, raw materials including essential oils and floral pomades, heavy goods, as well as boxes and packaging.

In 1912, as part of its redevelopment plan, Atkinsons also rebuilt the building in Old Bond Street. The refurbished building was constructed in an Arts and Craft style designed by the architect Charles Francis Annesley [1857-1941].

Above: 1911 Atkinson store at 24 Old Bond Street before the upgrade.

Above: 1912 Drawing of the redeveloped Atkinson store at 24 Old Bond Street.

Above: 1912 Drawing of the interior of the redeveloped Atkinson store at 24 Old Bond Street.

Eonia extracts

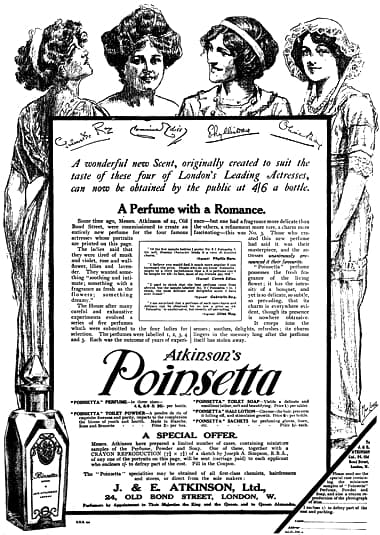

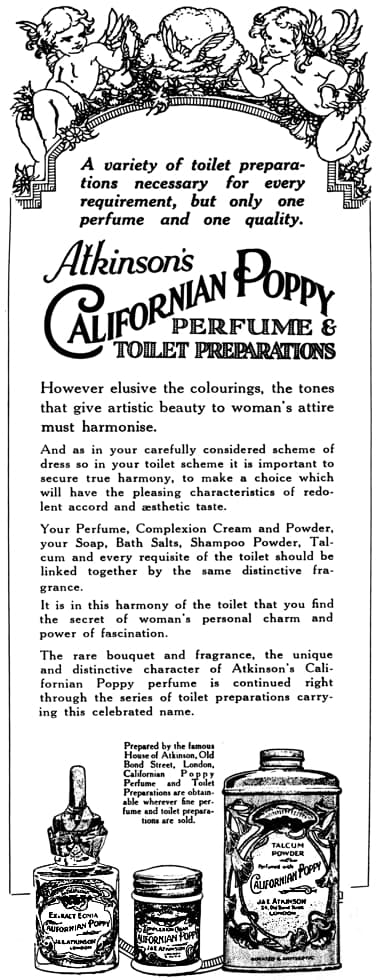

Before the Eonia Works was established, Atkinson began releasing a series of Eonia Extract flower fragrances under the trademark it had secured in 1902. This started with Violette and Jasmine but was followed with others including Californian Poppy (1905) and Poinsetta (1911). These perfumes were priced more cheaply than other Atkinson fragrances and may have included synthetics. Horace Barrett had received training in the essential oil industry and synthetics into a number of Atkinsons’ perfumes including a number of stronger perfumes that were more suited to the company’s growing markets in South America.

Above: Californian Poppy.

Poinsetta is notable as the first fragrance Atkinsons supported with a heavy advertising campaign. Company placements prior to this had been very restrained. Advertisements for Poinsetta were illustrated and featured testimonials from the actresses Phyllis Dare [1890-1975], Gabrielle Ray [1883-1973], Connie Ediss [1871-1934] and Olive May [1886-1947]. Despite the heavy promotion it was not as successful as California Poppy which went on to become one of company’s best-selling lines.

1920s

Like many other firms, Atkinsons was adversely affected by the First World War. Raw materials became difficult to access, the excise duty on spirits that the company used to make perfumes was raised, overseas markets were lost and the Eonia Works were damaged during an air raid in 1917.

Emerging from the war, one of the company’s first acts was to establish its first subsidiary. In 1919, J. & E. Atkinson (France) Ltd. (P.C.) was founded and a showroom was opened at 2 Rue de la Paix, Paris.

Above: 1923 Atkinsons’ Paris store behind the automobile.

The Parisian address added to Atkinsons’s prestige but the primary motivation for establishing the French company was probably to counteract adverse exchange rates and increased tariffs. Raised import duties and unfavourable rates of exchange were also the reasons behind Atkinsons establishing subsidiaries in South America and Australia along with factories in Argentina and Montevideo (1927), Chile and Brazil (1929), and Australia (1930).

Above: 1922 Atkinsons Old English Lavender Water.

Most cosmetics businesses boomed through the roaring twenties following the post-war slump of 1920-21 but Atkinsons’ profitability declined in this period. In 1923, the company posted a net profit of £51,031 but this had dropped to £28,003 by 1929. The decline may have been partly due to increased expenditure on capital works. In addition to constructing the previously mentioned overseas factories, Atkinson had also moved its wholesale showrooms to 79 Queen Victoria Street in 1922, and rebuilt its headquarters in Old Bond Street once more in 1926. Although Atkinsons is no longer there, the Old Bond Street building survived the Second World War and still stands today.

Above: Atkinsons Building at Old Bond Street.

Above: 1926 Interior views of the Old Bond Street store.

Sales at home may also have declined through increased competition. As well as Yardley and older French houses such as Guerlain, Bourjois and Houbigant, Atkinsons now had to cope with new entrants like Coty.

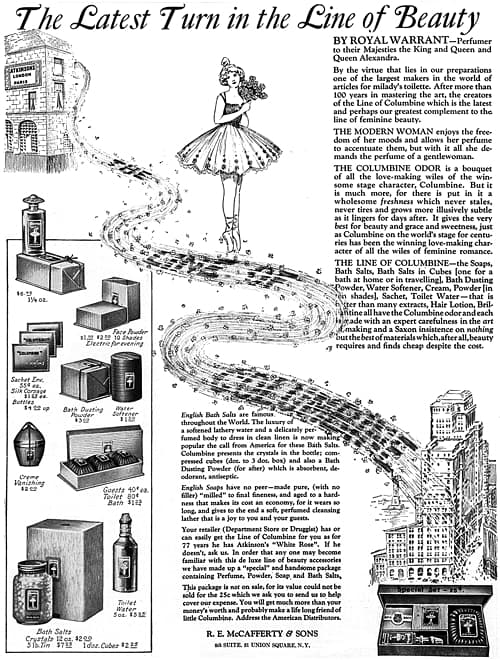

Above: 1924 Atkinsons imported by R. E. McCafferty & Sons, New York.

Lever Brothers

The 1920s also saw the beginnings of major changes in the ownership of Atkinsons. In 1920, it had issued 100,000 £1 shares to increase its capital base. Of these, 90,000 were bought by Joseph Crosfield & Son. Crosfield started as a soap company but had established the Erasmic Company as a subsidiary in 1890. Like Atkinsons, Erasmic produced perfumes, brilliantines, toilet and face powders, skin creams, milled toilet soaps, shaving soaps and toothpastes but was more downmarket. I imagine Crosfield envisaged some synergies emerging from its investment.

Crosfield had been bought by Lever Brothers Ltd. in 1919 so the share purchase also bought Atkinsons into contact with Lever Brothers. In 1929, Lever Brothers and the Dutch Margarine Union merged to form Unilever. Atkinsons would be completely integrated into Unilever by 1945 and its relationship with the conglomerate would have a profound effect on the company’s fortunes.

Timeline

| 1799 | Traditional date for the founding of the business. |

| 1813 | Business moves to 43 Gerrard Street, Soho. |

| 1818 | Business now at 44 Gerrard Street, Soho. |

| 1828 | Wholesale business at 44 Gerrard Street, with retail business opened at 39 New Bond Street. |

| 1831 | J. Atkinson renamed as J. & E. Atkinson after James Atkinson’s brother, Edward, is made a partner. |

| 1832 | Business moves to 24 Old Bond Street, London. |

| 1896 | J. & E. Atkinson Ltd. incorporates. |

| 1898 | Wholesale and export showrooms opened at 8 Wood Street, Cheapside. |

| 1910 | Wholesale, manufacturing and offices moved to the Eonia Works at Southwark Park Road, Bermondsey, London. Retail remains at 24 Old Bond Street. |

| 1912 | Old Bond Street shop remodelled. |

| 1919 | J. & E. Atkinson (France) Ltd. (P.C.) established. Showroom opened at 2 Rue de la Paix, Paris. |

| 1920 | Public issue of 100,000 £1 shares. Most acquired by Crosfield, a subsidiary of Lever Brothers. |

| 1922 | Wholesale showrooms moved from 8 Wood Street to 79 Queen Victoria Street, London. |

| 1926 | Old Bond Street shop rebuilt. |

| 1927 | J. & E. Atkinson Ltda SA, founded in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Factories opened in Argentina and Montevideo. |

| 1929 | SA de Perfumarias J. & E. Atkinson de Brazil founded. Factories opened in Chile and Brazil. |

Continue to: Atkinsons (post 1930)

First Posted: 6th April 2020

Last Update: 4th August 2022

Sources

The chemist and druggist. (1859-) London: Morgan Brothers.

Eonia works. (1911). The Chemist and Druggist, April 29, 135-137.

From bear’s grease to lightheart. A century and a half in the development of a London perfumer. (1949). The Chemist and Druggist, August 27, 286-288.

Morris, A. C. (1927). A history of perfumery: A record of events and a survey of progress from the earliest times. Perfumer and Essential Oil Record, July, 285-307.

A scent centenary. (1899). The Chemist and Druggist, June 3, 887.

Unilever archives. Retrieved February 26, 2020 from http://unilever-archives.com

1858 Gerrard Street, Soho. The central building is No. 43 next to No. 44 on the left.

1811 Atkinson’s Original Curling Fluid.

1813 Atkinson’s Original Curling Fluid and Atkinson’s Vegetable Dye.

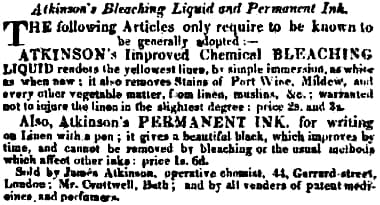

1822 Atkinson’s Bleaching Liquid and Permanent Ink. Atkinson advertised these items for a number years in the 1820s. In these advertisements he describes himself as an Operative Chemist.

1823 Bear’s Grease.

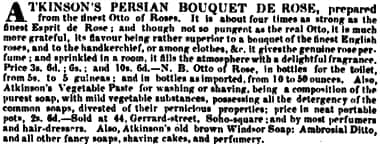

1825 Persian Bouquet de Rose.

1826 Atkinson’s Bear’s Grease.

1826 Atkinson’s Articles for the Toilet.

1826 James Atkinson Perfumer to the Royal Family.

1828 Atkinson’s Concentrated Essence of Lavender, Persian Bouquet de Rose, and Otto of Roses along with a great variety of continental perfumes including Farina Of Cologne and Chardin Houbigant of Paris.

1829 Atkinson’s Refined Camphor Soap.

1830 Atkinson’s Milk of Almonds.

1830 James Atkinson Articles for the Toilet.

1840 Atkinsons Ethereal Extract of Spring Flowers.

Eugene Vernon Barrett [1845-1925].

Horace Vernon Barrett [1872-1957].

1871 Atkinsons perfumes and soaps, India. Perfumes manufactured for export were made ‘In Bond’ so did not incur an alcohol duty and could be sold more cheaply than in the home market.

1886 Atkinsons English Perfumery (Australia).

1886 Artificial Perfumes.

1895 Atkinsons White Rose.

1897 Atkinson’s Aoline.

1897 Atkinsons Aoline (France).

1898 Atkinsons Eau de Cologne.

1899 Atkinsons Centenary Bouquet.

1903 Atkinson’s Violette-Eonia (France).

1911 Atkinsons Poinsetta.

1913 Old Bond Street store after redevelopment.

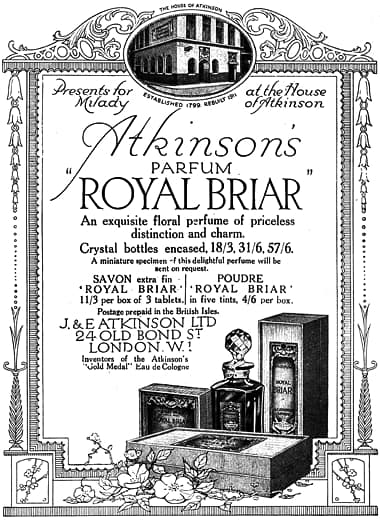

1918 Atkinsons Royal Briar.

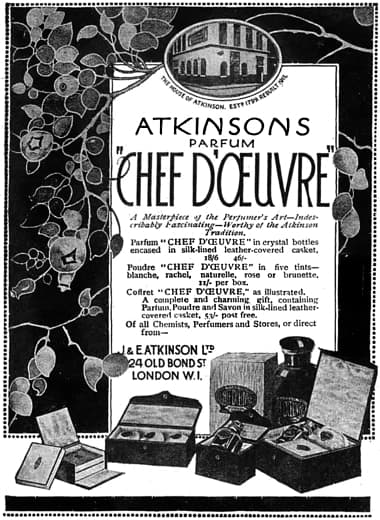

1919 Atkinsons Chef D’Oeuvre Parfum, Poudre, and Savon.

1920 J. & E. Atkinson Ltd. prospectus.

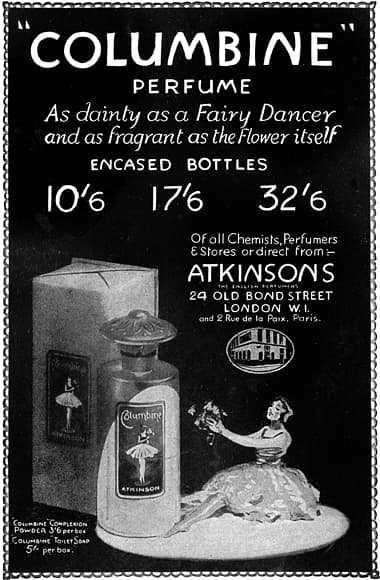

1923 Atkinsons Columbine Perfume.

1923 Atkinsons Columbine Complexion Powder.

1923 Atkinsons Californian Poppy Perfume, Complexion Cream and Talcum Powder.

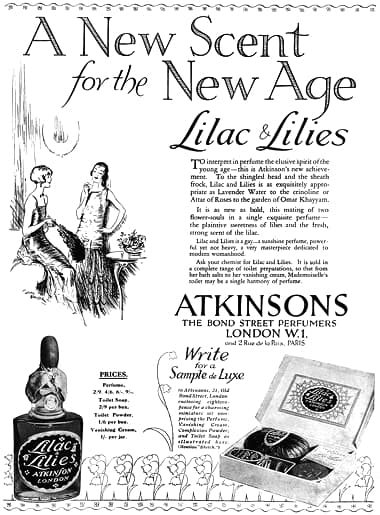

1924 Atkinsons Lilac & Lillies Perfume, Toilet Soap, Complexion Powder and Vanishing Cream. Also available as Bath Salts.

c.1925 Atkinsons’ Paris store at 2 Rue de la Paix designed by Louis-Charles Boileau [1837-1914] and Alexandré Lapanche [1839-1910].

Atkinsons at 24 Old Bond Street designed by Vincent Harris [1876-1971].

1926 Atkinsons Eau de Cologne.