Dubarry et Cie

This story covers the British Dubarry, which first appears as Dubarry et Cie, a company created by Harry William Kilby Pears [1869-1950] in Hove, East Sussex, England, in 1916. Unfortunately, some confusion exists between this Dubarry and another that had its origins with Richard Hudnut in the United States. There are a number of ways to spell the name of Jeanne Bécu, the Comtesse du Barry [1743-1793], the royal mistress of King Louis XV of France and this helps differentiate the two brands. Richard Hudnut chose to use Du Barry while those in Hove used Dubarry. This is not always obvious as the American company often conflated Du Barry as DuBarry in company advertising. Where you see this, note the two capitals.

Then we come to The Du Barry, or Dubarry. Do you wish, sir or madam, that they would make up their minds which way they are going to spell it? Yes, me too.

(Cousins, 1935, p. 30)

Potential legal conflict between the British and American companies appears to have been avoided by the British Dubarry electing to change the name of its Dubarry products in Canada to Dalcrose, a name it had trademarked in 1916, and by William R. Warner, the owners of Richard Hudnut, keeping the American Du Barry out of the other parts of the British Empire where the British Dubarry was sold. This may partly explain why William R. Warner created its Gemey range in the late 1920s. It became Warner’s premium range in countries like Australia where they were unable to sell their Du Barry cosmetics, the company’s premium range in the United States.

See also: Richard Hudnut (1920-1945)

Harry W. K. Pears

Harry Pears was the only son of Kilby Pears [1839-1912] and Sarah Augusta Robinson [1842-1900]. He graduated from Brighton Grammar School in 1886, passing his matriculation exams from London University. He then enrolled at the College of the Pharmaceutical Society in London (known colloquially as the Square). He was awarded a Jacob Bell Memorial Scholarship in 1889 and graduated the following year becoming a registered pharmaceutical chemist. As a Member of the Pharmaceutical Society (M.P.S.) he spent time at the Square and worked with a number of London manufacturers before moving back to Hove in 1898 to join his father’s pharmacy business.

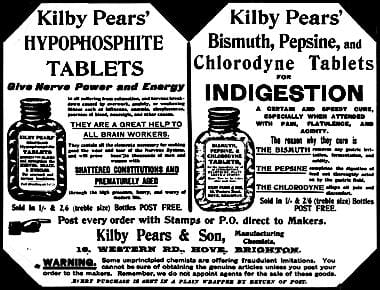

Harry Pears’ father, Kirby Pears, had been successfully operating his own pharmacy from 1870, move is chemist shop to 16 Western Road, Hove in 1874. I have no information that Harry Pears’ father was a manufacturing chemist but after Harry Pears joined the business and it became Kilby Pears & Son it began making a range of products sold under a Kilby Pears label. This suggests that Harry Pears was the driving force behind this new venture. The Kilby Pears label was short lived with Harry Pears establishing what was to become a much larger manufacturing business, The Standard Tablet Company, in 1901.

Standard Tablet

The Standard Tablet Company was founded at 16 Western Road, the site of Kilby Pears & Son. However, needing more space, Harry Pears leased a site adjoining the Hove Railway Station in 1902 and began manufacturing tablets there. This may have been when he created Goldstone Laboratories as the manufacturing side of his business. The name probably references the Goldstone monolith which generated a lot of interest when it was unearthed in 1900. It had been buried for many years after a farmer, William Marsh Rigden, got fed up with sightseers destroying his crops on their way to and from the rock and paid to have it put underground.

Above: 1900 Unearthing the Goldstone monolith which was relocated to Hove Park in 1906. Many claimed it had been used by Druids.

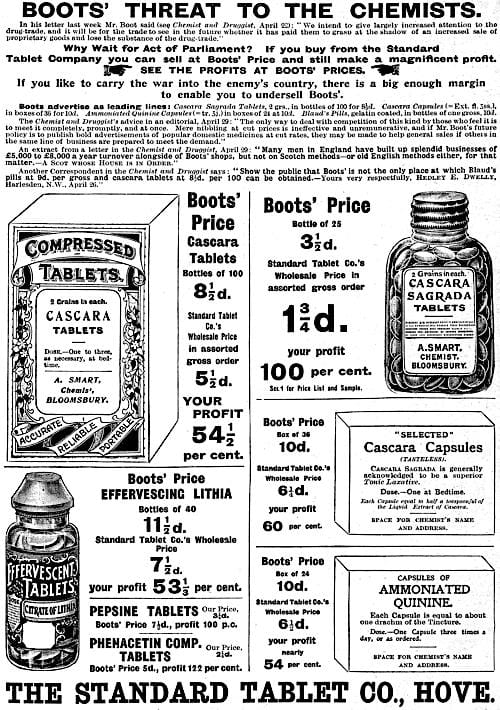

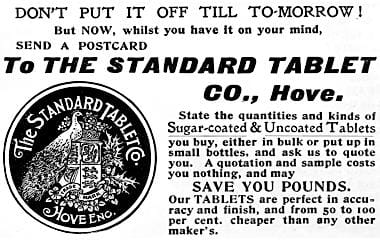

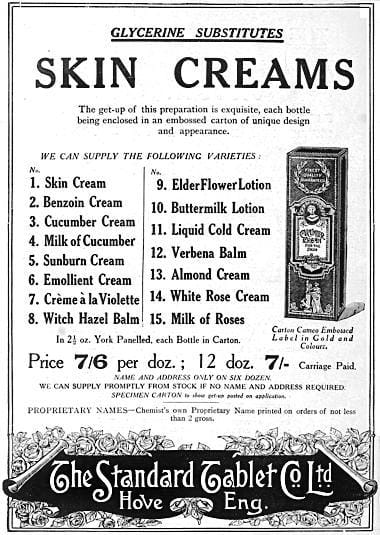

Standard Tablet made medicinal and patent medicines sold under its Ankh, Standard and other brands but would also labelled them in the chemist’s name if the order was large enough. Small British pharmacies were under increasing pressure from chains like Boots that sold a wide range of products at cheap prices. These chain pharmacies had began to proliferate in Britain after 1880 when, following a legal case, the Law Lords agreed that companies as well as individuals could operate a pharmacy. Buying products from Standard Tablet & Pill or similar suppliers helped keep small chemist shops in business.

Above: 1905 Trade advertisement for The Standard Tablet Company. Jesse Boot [1850-1931] operated a chain of 250 shops by 1900.

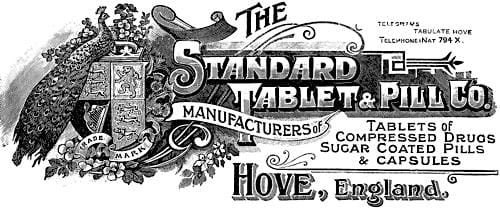

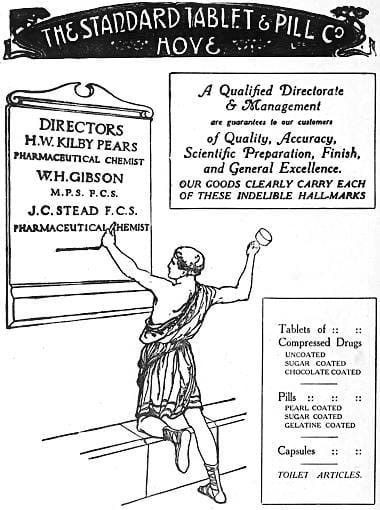

Standard Tablet expanded rapidly and, after adding pills and capsules to its range, changed its name to Standard Tablet & Pill in 1906.

Above: 1909 Standard Tablet & Pill.

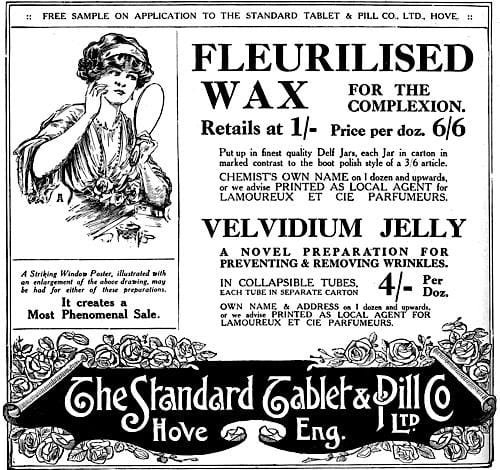

By 1909, it had branched into cosmetics and toiletries most notably through its Standard Series which included soaps and toothpastes in a range of fragrances, a number of skin creams, and some perfumes.

Above: 1909 Trade advert for the Standard Series of toilet preparations.

By 1910, Standard Tablet & Pill had 100 employees and was selling its wares throughout the United Kingdom, India, South Africa, Australia, and the United States. The Goldstone factory had been expanded in 1908 and, as it was no longer needed, the pharmacy on Western Road had been sold.

In 1910, Harry Pears decided to turn Standard Tablet & Pill into a limited liability company (capital £15,000) and the 15,000 shares on offer were quickly taken up by residents of Hove and Brighton. Harry Pears held some of these and stayed on as the company chairman and managing director. Once formed, the new company took over the operations of Goldstone Laboratories.

Dubarry et Cie

In 1915, Harry Frank Slack [c.1890-1953] left Boots and came to work for Standard Tablet & Pill. He modified their tablet compressing machines so that they could be used to make bath tablets (Chapman, 1975, p. 95) which the company began selling in 1916. However, rather than doing this through Standard Tablet & Pill the sold them through a newly created company – Dubarry et Cie.

When Dubarry et Cie was founded In 1916, Britain was in the middle of the First World War and some have suggested that the Dubarry et Cie name was chosen to honour Britain’s French allies. However, I doubt that the French would have enjoyed an English company using a french-sounding name to sell perfumes. It is more likely that the French title was used to add credibility to the company’s perfumes, French perfumes then being generally considered to be the best in the world. Standard Tablet & Pill had tried this faux-french tactic once before when they began selling Fleurilised Wax and Velviduim Jelly in 1912. Their recommendation to retailers, who were not going to use their own name, was to have the labels printed with ‘Local agent for Lamourux et Cie Parfumeurs’, a fictitious French company.

Above: 1912 Trade advert for Fleurilised Wax and Velvidium Jelly.

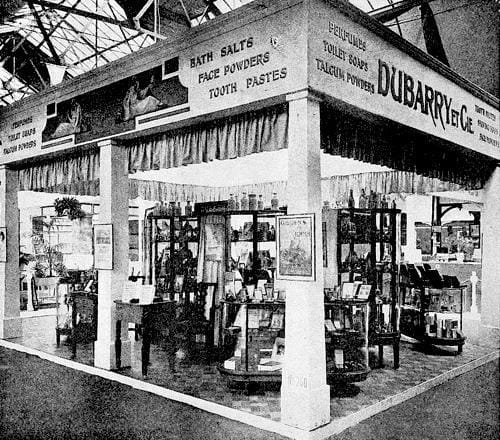

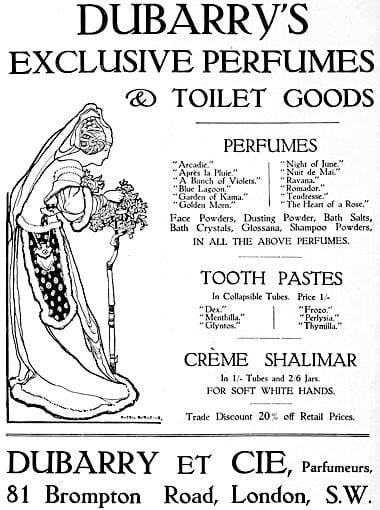

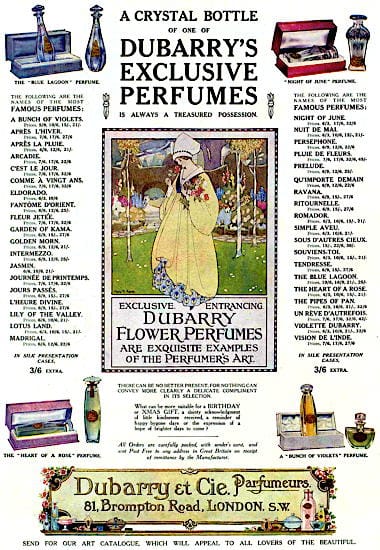

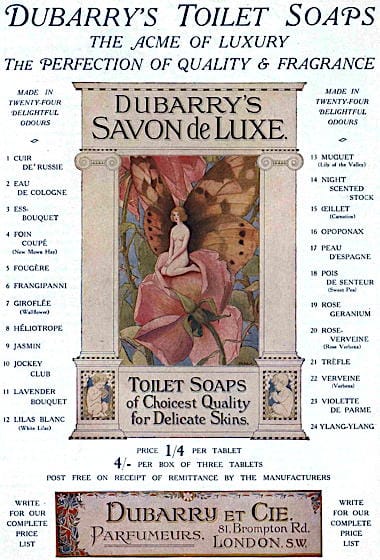

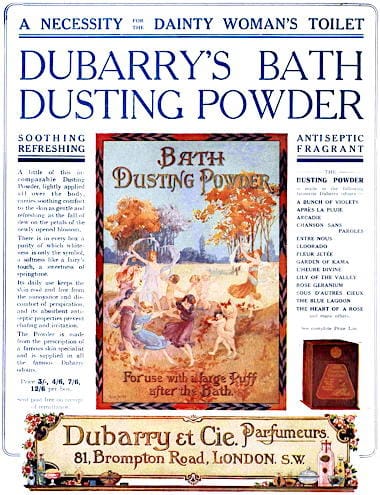

The creation of Dubarry et Cie allowed Standard Tablet & Pill to expand their sales of cosmetics and toiletries into department and other stores while keeping their existing pharmacy customers onside. The strategy had four main parts. The first part was to create a new company with an attractive name; i.e., Dubarry et Cie. The new business was then given a prestigious London address at 81 Brompton Road in Knightsbridge close to Harrods to add additional cachet. Products of the new firm were given high quality packages which were then promoted through an extensive advertising campaign. This ran between 1917 and 1919 with over £20,000 spent promoting the range, only easing off after then as the company had trouble keeping up with demand. Some of Dubarry’s most beautiful advertisements come from this period.

The expanding operations of Dubarry et Cie put a good deal of pressure on Goldstone Laboratories. Land adjacent to its leased site in Hove was bought and new factories were built to service the increased demand.

Above: 1922 Dubarry et Cie display at a trade fair.

Dubarry Perfumery Company

In need of more capital, the Dubarry Perfumery Company Ltd. (capital £150.000) was created in 1923. Harry Pears continued on as chairman and managing director, Archibald Vickers became its sales director, and Harry Frank Slack was made general manager.

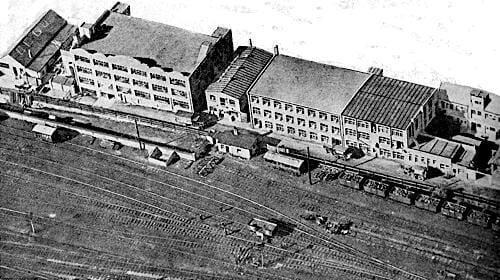

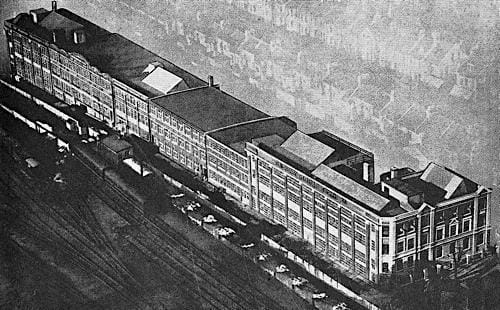

Above: 1923 Dubarry Perfumery (Goldstone Laboratories).

After it was established, Dubarry Perfumery acquired Standard Tablet, which had changed its name to The Standard Tablet Company Ltd. in 1917, and Dubarry et Cie, both subsidiaries continuing business as usual. Standard Tablet handled the pharmaceutical operations, Dubarry et Cie perfumes, cosmetics and toiletries. Both firms had their products supplied by Goldstone Laboratories, now greatly expanded.

Products

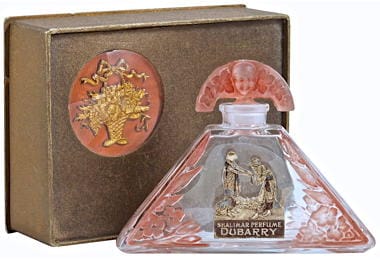

Dubarry et Cie started out primarily as a seller of perfumes. By 1918, it had about fifty different fragrances in its inventory each produced in three or four different sizes, also available in a concentrated ‘drop’ bottle. Many of these were housed in attractive glass containers designed by the French designer Julien Henri Viard [1883-1938] and were manufactured by the French glassworks established by Maurice Depinoix [1860-1945]. Duncan (2015) reports that these French glass bottles were imported clear and were given a satin finish in the Goldstone factory. Boxes for the perfumes and other products look to have been designed and produced in Hove. The company had its own printing works using designs produced by its Art Department.

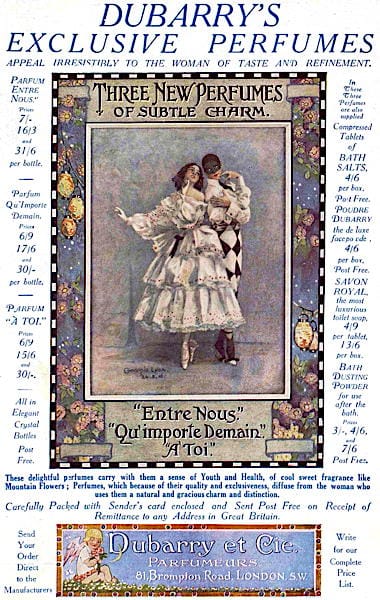

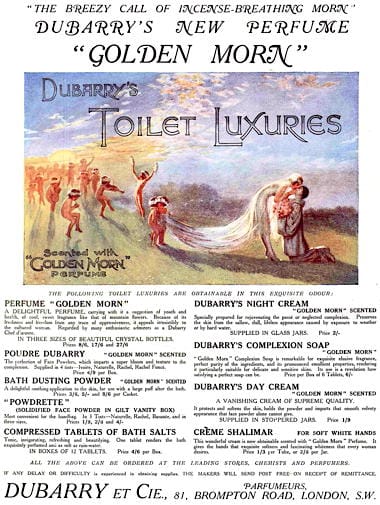

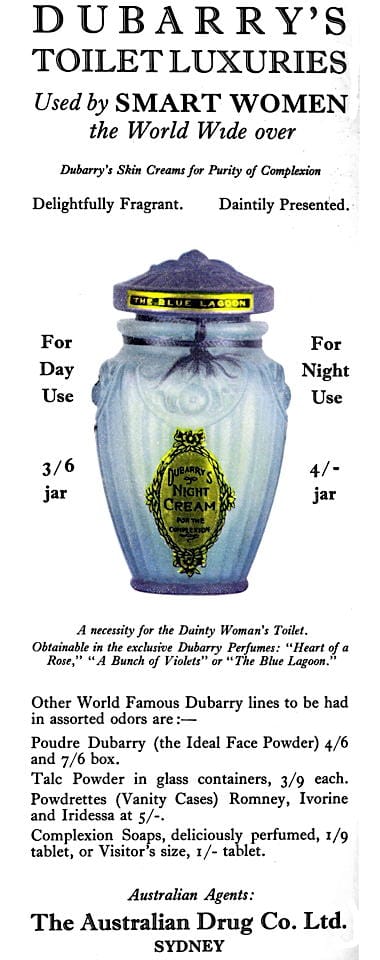

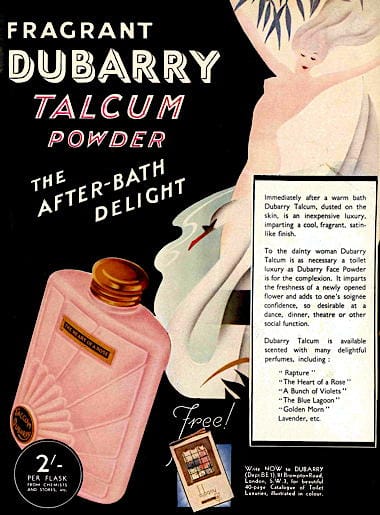

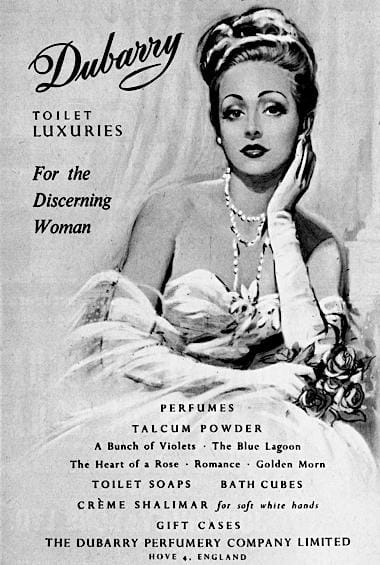

Some of the perfumes were given French names, such as Souviens-Toi and Nuit de Mai, but others, like Garden of Kama and The Blue Lagoon, used English titles. The perfumes came in a range of price points, some being double the price of the cheapest scents. Violet and rose fragrances had been popular in the Edwardian period and Dubarry had both covered with A Bunch of Violets, Violette Dubarry, and The Heart of a Rose. Golden Morn and The Blue Lagoon were also popular.

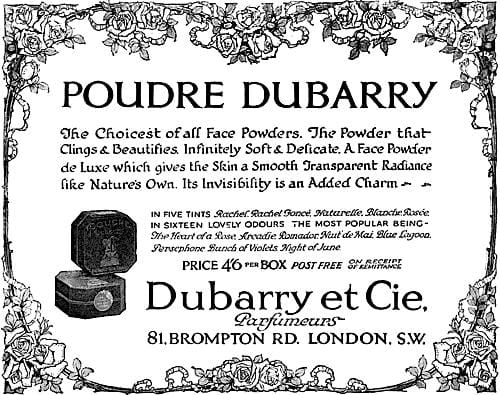

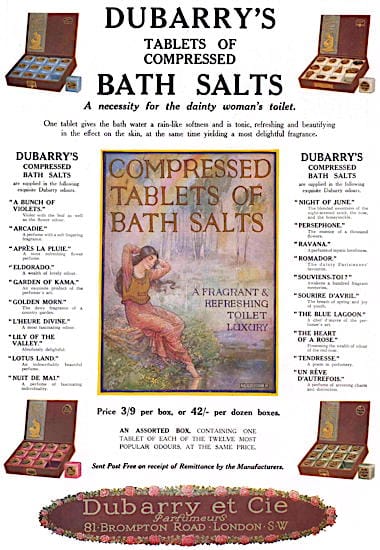

Some Dubarry perfumes were used to scent a range of auxiliary products such as face powders, dusting powders, bath salts, bath crystals, soaps, and shampoo powders. For example, Poudre Dubarry could be purchased in one of sixteen different ‘odeurs’ including: The Heart of Rose, Arcadie, Romador, Nuit de Mai, The Blue Lagoon, Persephone, A Bunch of Violets, and Night of June.

Above: 1916 Poudre Dubarry.

Skin-care

Dubarry moved quickly into cosmetics and had a number of skin creams in its inventory by 1920 under a variety of names, many in French; e.g. Creme Printaniere, and Creme de Fraicheur. This is not surprising as Standard Tablet had been making and selling skin creams for years. Their pharmaceutical origins perhaps explains why some were supposedly based on a doctor’s prescription; e.g., Creme à la Glycerine (Mattei’s Prescription), Creme Velysia (Lassar’s Prescription), and Creme de Nuit (Dalcrose’s Prescription). I have no evidence that any of these doctors existed.

Creme de Beauté: “A pure emollient night cream for normal skins. A nutritive application for the skin, preserving its suppleness and texture. Its special recommendations are its extreme purity and harmlessness, and it is eminently adapted for regular use by the fortunate possessor of a good complexion who wishes to retain its natural beauty for as long as possible.”

Creme Printaniere: “A day cream. A greaseless vanishing cream of supreme quality. Excellent for skins having a super-abundance of natural secretions or with a tendency to become shiny. Excellent as a foundation for powder, used in which way it protects from sunburn.”

Creme à la Glycerine: “Particularly recommended when the skin is very rough or chapped by exposure to severe weather, or is severely sunburnt.”

Creme Velysia: “The purest and most efficacious skin food and complexion tonic known to medical science, and it is unfortunate that the elaborate processes involved in its manufacture and the costliness of its ingredients prevent it being within the reach of a larger circle. It cleanses the pores and produces a clear, radiant complexion; it beautifies, refreshes and rejuvenates.”

Creme de Nuit: “For sallow and muddy complexions. Increase the circulation and activity of the skin. Rejuvenates the passé or neglected complexion.”

Creme de Fraicheur: “Applied during the day as a foundation for powder, it is very superior in this respect to vanishing cream, being free from the drying effect of the latter, also more comfortable in use. … [U]sed in this way, [it] renders the complexion proof against sunburn. It is excellent for application after washing the face at bedtime, whenever it is inconvenient to use the solid creams. The cream is neither greasy nor sticky, and is a gentle, soothing skin tonic. Recommended as a preserver of the complexion.”

Dubarry also sold lotions such as Lotion du Docteur Dalcrose, also known as Docteur Dalcrose Sunburn Lotion in some parts of the world. This is the same doctor that was associated with Creme de Nuit. Lotion du Docteur Dalcrose was applied like a liquid powder and could be used as such. However, its primary purpose was to soothe and cool sunburnt skin.

Lotion du Docteur Dalcrose: “[H]as a wonderful cooling and soothing effect where the skin has been burnt by exposure to the sun, and quickly removes inflammation, redness and soreness.”

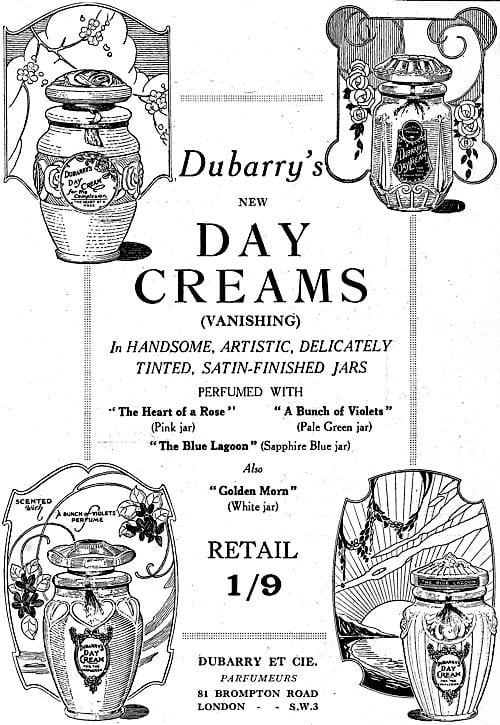

In 1922, Dubarry launched its Golden Morn series using the popular Golden Morn perfume it had introduced in 1916. Included in the series was a Dubarry Day Cream, and a Dubarry Night Cream, the first time I have seen Dubarry name its skin creams by function.

Dubarry Day Cream and Dubarry Night Cream look to have been rebadged Creme Printaniere and Creme de Nuit respectively, perhaps the only difference being that these new creams were scented with Golden Morn. As the decade progressed other day and night creams were added by Dubarry each scented with a different fragrance. These were placed in differently coloured jars to make recognition easier – Golden Morn (white), Blue Lagoon (blue), Heart of Roses (pink), and Bunch of Violets (pale green).

Above: 1927 Dubarry Day Creams.

See also: Day and Night Creams

Make-up

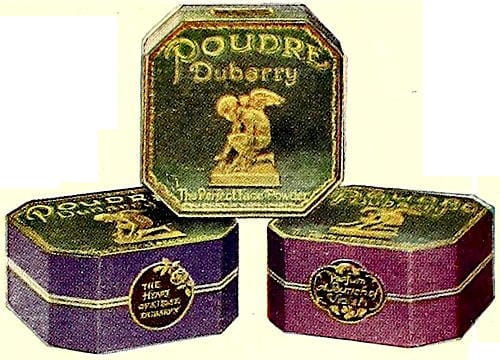

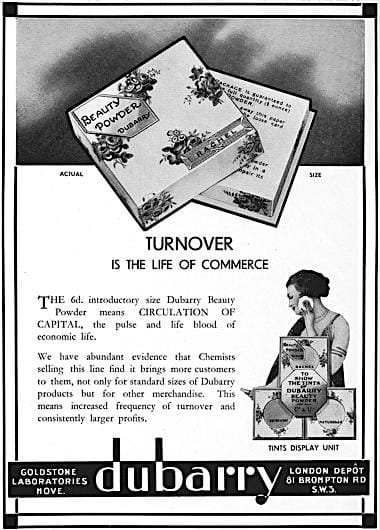

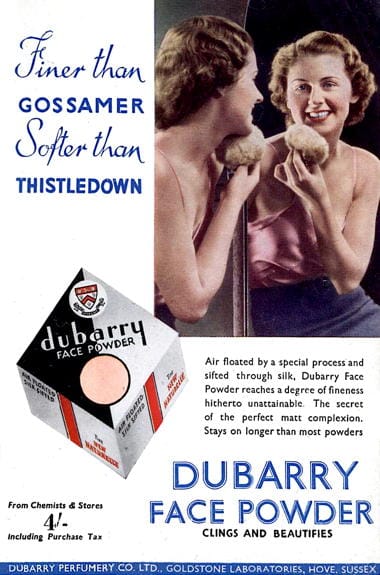

Like some of Dubarry’s early skin creams some early Dubarry face powders were also ascribed to doctors. These early powders, which included La Milo, Poudre de Riz du Dr. Villars, Poudre Dubarry, Poudre de Beauté Cartier, Poudre de Riz Mattei, and Poudre de Beauté du Docteur Dalcrose, ranged wildly in price, going from Poudre Dubarry at 4 shillings and 6 pence a box to Poudre de Beauté du Docteur Dalcrose at 21 shillings.

Above: 1924 Poudre Dubarry.

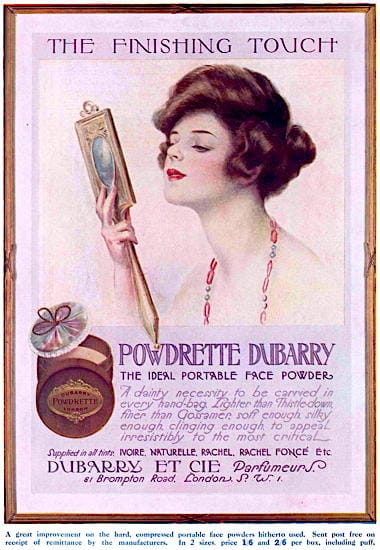

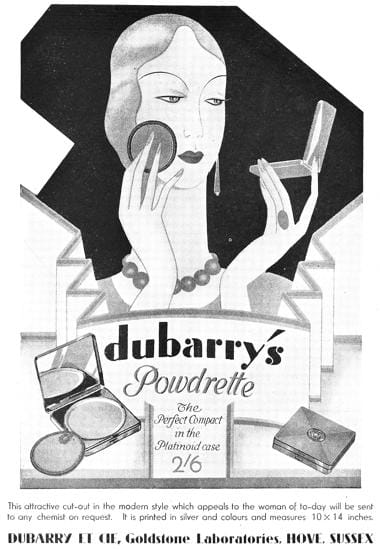

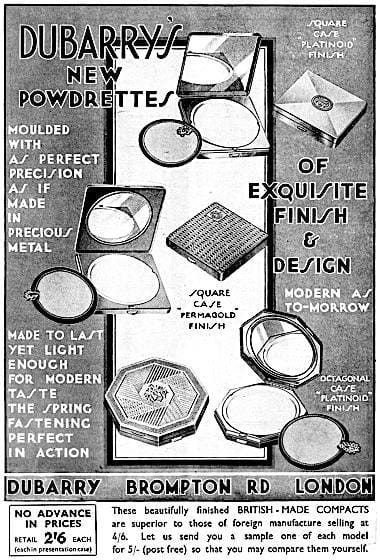

Of these face powders only Poudre Dubarry received substantial amounts of advertising. In 1919, it was complemented with Dubarry Powdrette, a compact powder scented with Fleur Jetée, Chanson sans Paroles, Jasmin, or Romador perfume that could be carried in a purse or handbag. Produced in the same shades as Poudre Dubarry, the powder cakes used in the first Powdrettes were not produced by compression. It seems likely that they were made by wet moulding, an older technique for making compact face powders and rouges. I expect that Dubarry probably switched to compressed powders later on.

See also: Compressed Face Powders.

By 1920, the company had also added Dubarry Liquid Powder. This sort of make-up was generally formulated as a powder suspension and was used to even out and whiten the skin of arms, décolletage and other parts of the body exposed by more revealing evening wear. I have no reason to suspect that the Dubarry version differed from other similar products.

See also: Liquid Face Powders

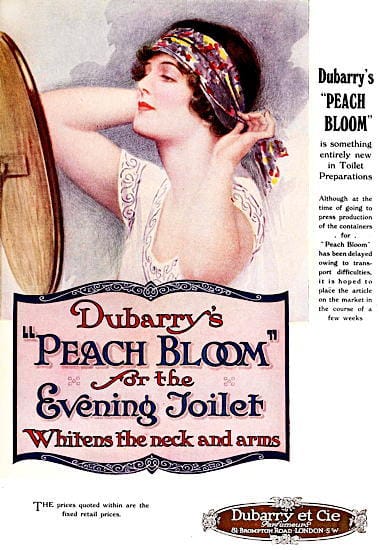

In 1926, Dubarry introduced an alternative to the Dubarry Liquid Powder, introducing a powder cream called Peach Bloom. It was applied with a moistened rubber sponge that would turn the powder cream into a liquid powder on application. Because of this, it was packaged in an oxidised aluminium box to avoid problems with the water rusting the container.

By 1930, Dubarry had also added Shalimar Powder Cream, a combination of powder and vanishing cream that could be used by itself or in combination with a face powder. Packaged in jars, I don’t have any indication that it came in a range of different shades.

Poudre Dubarry: ”The powder that clings and beautifies. Infinitely soft and delicate. A face powder de luxe which give the skin a smooth transparent radiance like Nature’s own. Its invisibility is an added charm.’ Shades: Rachel, Rachel Foncé, Naturelle, Blanche, and Rosée with Ivoire, Rose Foncé, and Basanée added in 1917.

Dubarry Powdrette: “It imparts a smooth transparent radiance to Nature’s own. In dainty box with puff.” Initially available in all Poudre Dubarry shades but this had been reduced to Rachel, Naturelle, Ivoire, and Basanée by 1924.

Dubarry Liquid Powder: “[I]nvaluable for evening use, before going to a dinner party of dance. Excellent for applying to the arms and neck where traces of exposure to the sun persist. The powder remains on the skin until washed off.” Known shades: Rachel, and Naturalle.

Dubarry Peach Bloom: “[S]pecially intended for the evening toilet, for whitening the neck and arms. For this purpose it is much superior to and more convenient in use than the ‘Liquid Powder’ type of preparation.”

Shalimar Powder Cream: “A combination of powder and vanishing cream which may be used alone or as a foundation for rouge and face powder, which cling so much better when the skin is treated with this cream. Essential to the smart woman’s make-up as it is the secret of that much desired matt finish to the skin which is so effective.

Above: c.1927 Window display for Dubarry in Rochdale, England.

Lipstick and rouge

I have no evidence that Dubarry made a rouge or lipstick until the 1920s. This is surprising as the manufacture of powder rouge is similar to that for making face powder. The earliest reference I have for a Dubarry rouge comes from the Extensor Vanity Box, a triple, gold-plated compact with mirror and puff introduced in 1924. These contained a solid Powdrette Face Powder in either Rachel or Naturelle shade and a small solid rouge in a single shade.

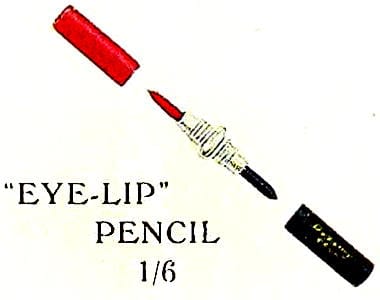

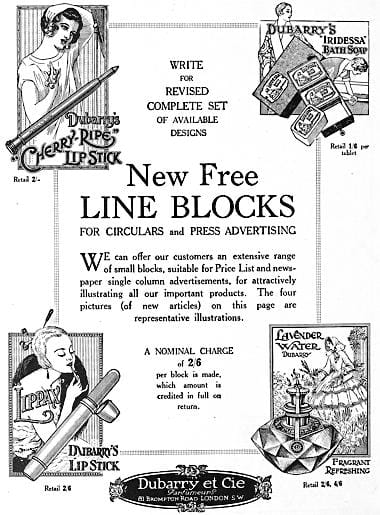

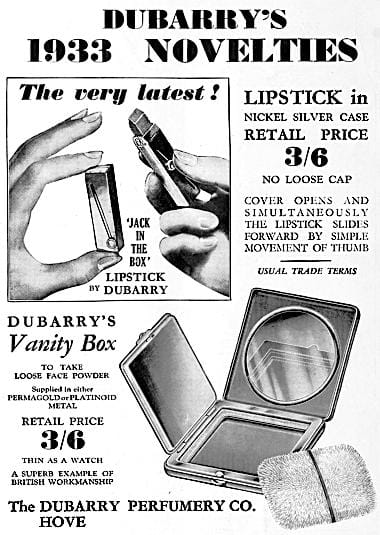

Dubarry did sell a lip salve called Lippax early on. By 1926, this had been put into a new metal twist-up case with a hinged top and was now referred to as an indelible lipstick. It apparently came in a range of shades but I have no information as to what they were. Dubarry was also selling a thin Cherry Ripe Lipstick by then which looks to have functioned as a lip pencil.

Dubarry Lippax: [A]vailable in a new gold-finished, rotary-propelling, pencil-type case. Pleasant and effective, it not only protects the lips in all weather, but the tinted varieties also impart a beautiful natural colour, absolutely free from any greasy appearance.”

A third lip product arrived in 1928 when Dubarry added its Eye-Lip Pencil which, as its name suggests, was a dual purpose device containing a crayon for the lips at one end and another for the eyebrows at the other. To make it easy to select the right crayon, the case covering was coloured red at the lip end and black at the eyebrow end. The lip crayon came Cerisette, Capucine, and Electrique shades, the eyebrow crayon in Brun, Noir, and Bleu. Both crayons were to be applied over moistened lips and eyebrows and were said to be waterproof. The Eye-Lip Pencil was the only make-up Dubarry produced for the eyes in the 1920s that I know of. I have found no evidence that the company made a block/cake mascara or kohl during this time.

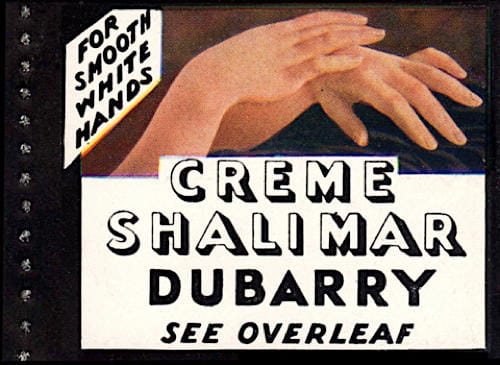

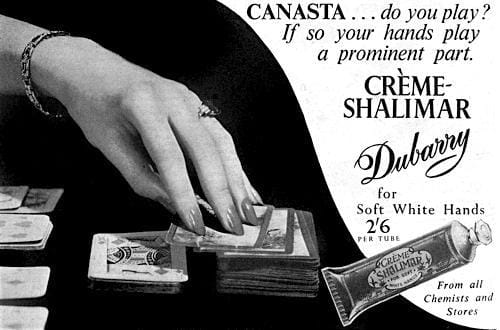

Shalimar

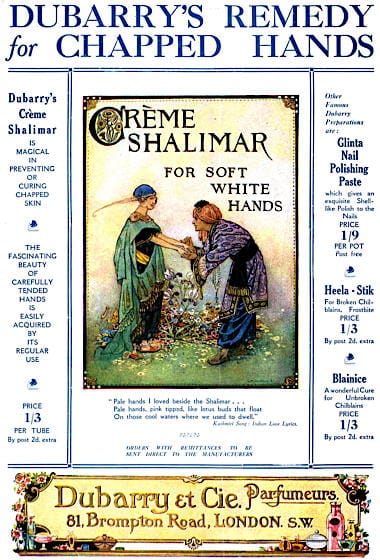

I have singled out Shalimar as it was one of Dubarry’s most popular lines. The series began with Crème Shalimar, a hand cream, introduced in 1916 in tubes and glass jars in three different fragrances – A Bunch of Violets, Garden of Kama, and Persephone. Dubarry appears to have created a Shalimar perfume at a later date and this may have been used in later versions of the hand cream and later Shalimar lines. The first of these were ancillary cosmetics for the hands – Lotion Shalimar, Shalimar Cleansing Powder, and Savon Shalimar. Later products ain the series included the previously mentioned Shalimar Powder Cream, as well as Poudre Shalimar, Shalimar Hair Cream, Shalimar Solidified Brilliantine, and Shalimar Liquid Shampoo. These were mostly Shalimar versions of existing products. For example Dubarry’s Glinta Solidified Brilliantine was available well before it added Shalimar Solidified Brilliantine.

Crème Shalimar: “The fascinating beauty of soft white hands is easily acquired by the regular use of this preparation. Crème Shalimar is wonderful in its effect on chapped hands.”

Lotion Shalimar: “[A] non-greasy preparation that is appleid during the day time; it possess full emollient qualities, and produces soft white hands.”

Shalimar Cleansing Powder: “[F]or removing stains of every description from the hands, including fruit stains, garden and household stains.”

Shalimar Powder Cream: “A combination of powder and vanishing cream which may be used alone or as a foundation for rouge and face powder, which cling so much better when the skin is treated with this cream. Essential to the smart woman’s make-up as it is the secret of that much desired matt finish to the skin which is so effective. ”

Shalimar Solidified Brilliantine: “[F]or fixing the hair in any desired position, and giving a glossy appearance.”

Shalimar Liquid Shampoo: “Imparts a lustrous beauty and gives vigour to the scalp and health to the hair. It brings out the glorious highlights of the hair so much admired.”

Nails

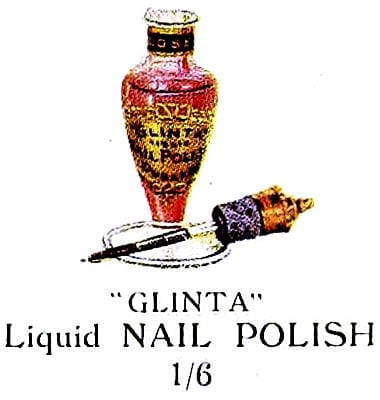

Dubarry sold a range of cosmetics for the nails including Glinta Nail Polishing Paste in a Wedgwood bowl, Glinta Nail Polishing Stone, Glinta Cuticle Cream, Cutidel cuticle solvent, and Nail Cleansing Fluid along with standard manicure equipment such as emery boards and cuticle sticks. These were combined in manicure kits, some with Shalimar cosmetics.

In 1925, Dubarry added Glinta Liquid Nail Polish packaged in a glass bottle shaped like a Greek vase with a built-in, camel-hair brush. It may have only come in a single shade &nash; Shell Pink.

Sun-care

Until the 1920s, British women were expected to stay out of the sun and wear physical protection such as hats, veils and gloves when venturing out. As mentioned earlier, Dubarry claimed that a number of cosmetics would help protect the skin from the sun but the face powder applied over them would probably have been a more effective.

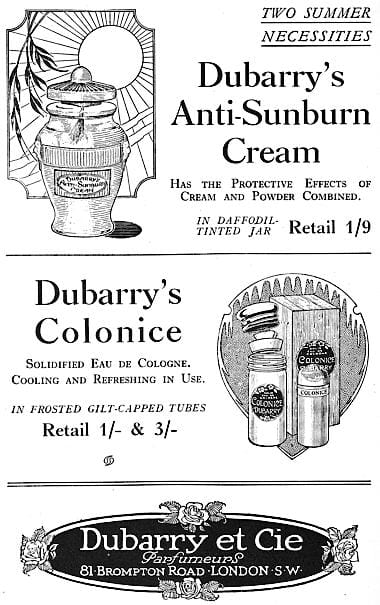

In 1927, Dubarry debuted Anti-Sunburn in daffodil-tinted jars which it claimed would protect the skin from sunburn and soothe sun-damaged skin. Unfortunately, have no information about its composition.

Anti-Sunburn Cream: “It protects the skin from sunburn and imparts a smooth sun-resisting, peach-like appearance. It prevents freckles. To those who have already become sunburnt it will be found a boon in removing the redness in relieving, cooling and healing.”

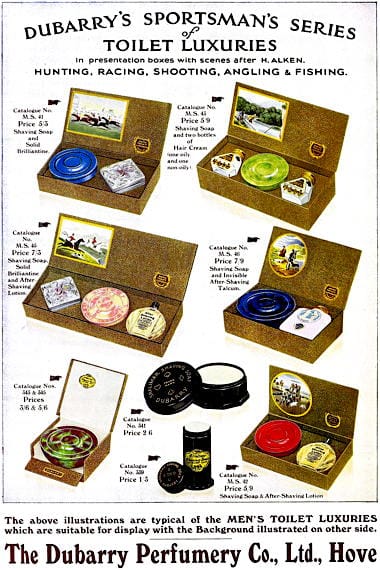

Men’s toileries

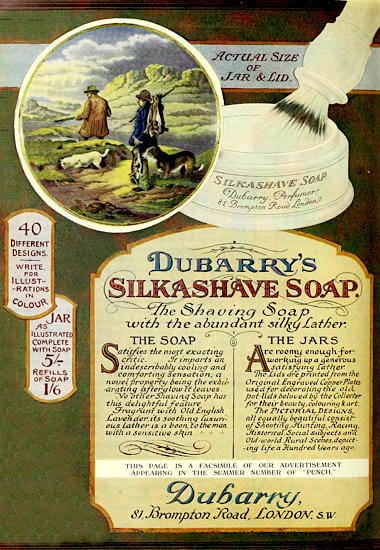

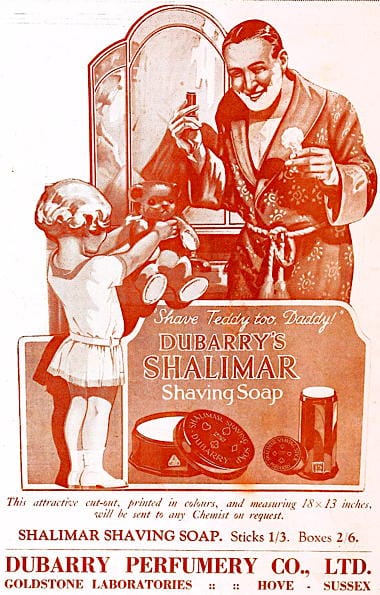

Dubarry introduced a number of shaving products in the early 1920s. These included Silkashave Shaving Soap packaged in a bowl in a range of fragrances, Silkashave Shaving Stick, and Debonair Shaving Milk, a liquid soap.

Silkashave Shaving Soap: “Fragrant with Old English Lavender, its soothing luxurious later is a boon to the man with a sensitive skin.”

Silkashave Shaving Stick: “A shaving soap with an absolutely distinctive feature, containing a certain ingredient which produces an indescribable cooling and comforting sensation.”

Debonair Shaving Milk: “A few drops only rapidly yield a thick, fragrant, lasting lather.”

1930s

By 1931, Dubarry Perfumery had purchased its original leasehold site and had built a number of new factories on the additional land it had acquired creating a set of buildings that still largely exists today.

Above: 1932 Dubarry Perfumery (Goldstone Laboratories).

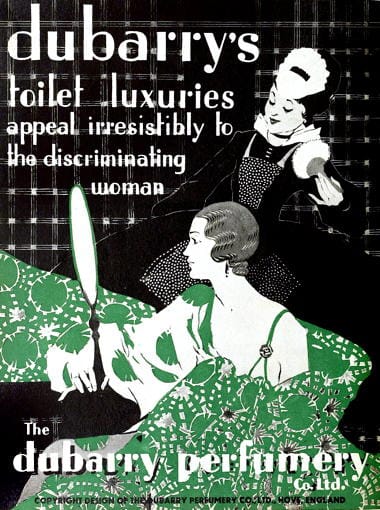

By then the Great Depression of the 1930s has set in and British people were being urged to buy British to support the ailing British economy. This meant that Dubarry’s French-sounding Dubarry et Cie brand became something of a liability. In response, Dubarry largely dropped the title after 1930 replacing it with Dubarry or Dubarry Perfumery and accompanied it with statements stressing that Dubarry was British owned and that the company manufactured in Britain.

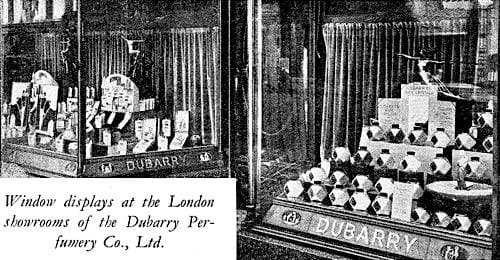

Depressed cosmetic sales may also have been behind Dubarry’ decision to shut down the Dubarry shop in Brompton Road in 1937. However, it might also reflect Dubarry’s renewed interest in the pharmaceutical side of its business. In 1938, Dubarry Perfumery had founded two new companies, Quality Chemists Ltd. (capital £100) and Laking Chemical Co. Ltd. founded (capital £100). Both opened London offices at 58a Brompton Road, Knightsbridge, down the road from the now closed Dubarry store. The director of Quality Chemists was Carl Lovell Von der Heyde [1875-1948] the husband Edith Sarah Beatrice Pears. I assume manufacturing was done in Hove.

Above: 1936 This is the only image of the Dubarry Shop at 81 Brompton Road that I have seen.

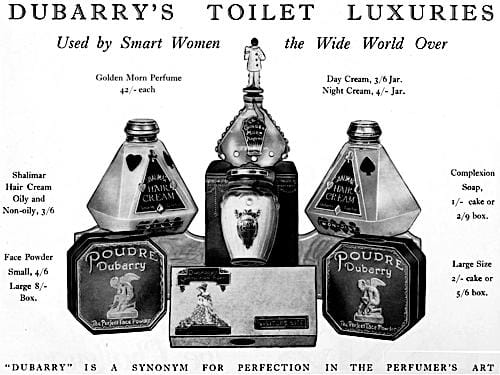

Like many other cosmetic companies, Dubarry responded to the Great Depression by modernised the packaging of many of its products, hoping that this would make them more attractive and increase sales. Starting with Shalimar Hair Cream (1930), many of these new containers used deco-esque designs.

Above: 1930 Dubarry Toilet Luxuries: Shalimar Hair Cream (Oily and Non-Oily), Golden Morn Perfume, Dubarry Day Cream, Poudre Dubarry, and a box of Dubarry Complexion Soap (Australia).

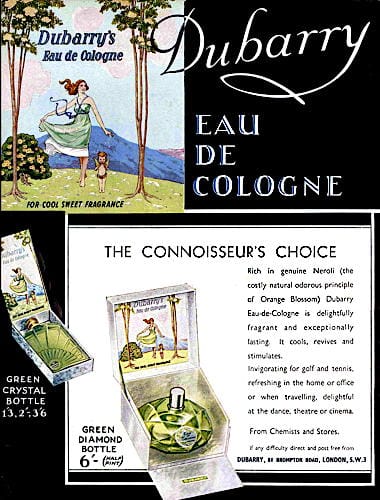

One of the more striking examples of the new style was the blue ‘diamond’ bottles produced for Rapture, a new perfume introduced in 1934. These bottles were subsequently reproduced in green for Dubarry Eau de Cologne.

See also: Rapture. A new perfume by Dubarry (c.1934)

Modernisation also saw some cosmetic containers replaced with cheaper alternatives such as Duralite. This early plastic was cheaper, was less likely to break when dropped, and was unaffected by water, making it particularly useful when packaging shaving soaps. All the Duralite containers I have seen were produced by Bellevue Fine Arts Ltd., Hove. I have been unable to find out anything about the company, when it was founded or how it operated. However, it may have been a Dubarry subsidiary as they owned it in 1953.

An examination of the new products introduced by Dubarry during the 1930s reveals a decided lack of innovation with the company becoming increasingly reliant on its bathing products – dusting powders, bath salts, bath crystals, and soaps – and Crème Shalimar to generate sales.

Dubarry did get more innovative with its marketing. In 1936, it entered into an agreement with the General Post Office to include images of its products in booklets of stamps and continued to do so through to the outbreak of the Second World War.

Above: Cover of a booklet of stamps advertising Creme Shalimar.

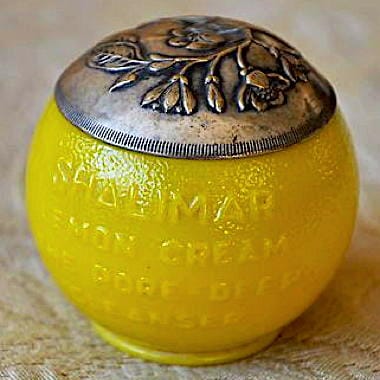

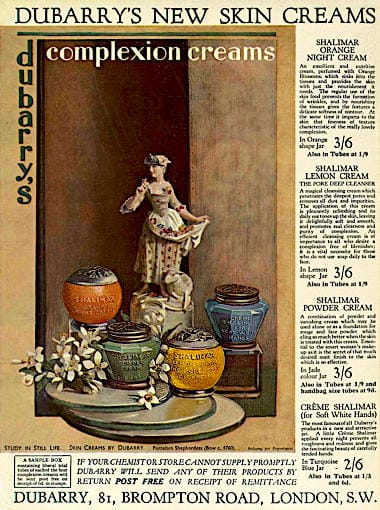

Skin-care

Two new Shalimar skin creams – Shalimar Orange Night Cream, and Shalimar Lemon Cream, were added in 1931. Both creams were packaged in novel containers; the Orange Night Cream in an orange glass jar moulded to look like an orange with the Lemon Cream similarly housed in a yellow, lemon-shaped glass jar. Shalimar Powder Cream and the bottled version of Crème Shalimar were also given more new glass containers. The lids of all of these containers were topped with a floral design that was more Arts and Crafts/Arte Nouveau than Arte Deco. This pattern was also used on the lids of boxes of Shalimar Solid Brilliantine.

Shalimar Orange Night Cream: “An emollient and nutritive cream, perfumed with Orange Blossoms, which sinks. into the tissues and provides the skin with just the nourishment it needs. The regular use of the skin food prevents the formation of wrinkles, and by nourishing the tissues gives the features a delicate softness of contour. At the same time it imparts to the skin that fineness of texture characteristic of the really lovely complexion.”

Shalimar Lemon Cream: “A magical cleansing cream which penetrates the deepest pores and removes all dust and impurities. The application of this cream is pleasantly refreshing and its daily use tones up the skin, leaving it delightfully soft and smooth, and promotes real clearness and purity of complexion. An efficient cleansing cream is of importance to all who desire a complexion free of blemishes; it is a vital necessity for those who do not use soap daily to the face.”

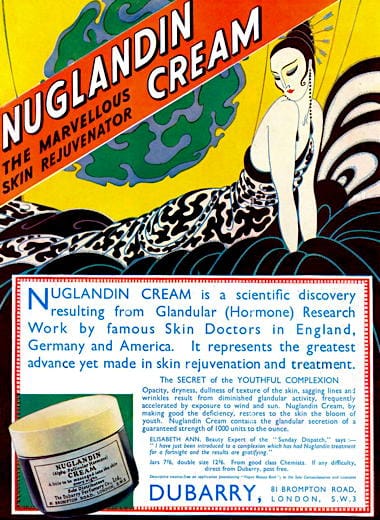

In 1936, Dubarry introduced Nuglandin Cream containing 1000 units per ounce of alpha-follicular hormone that was to be massaged into the skin before retiring at night. This is the first and only Dubarry skin cream with a ‘biological’ additive that I know of. I have not come across any mention of minerals, vitamins or other special ingredients added to Dubarry skin creams

Nuglandin Cream: “Opacity, dryness, dullness of texture of the skin, sagging lines and wrinkles result from diminished glandular activity, frequently accelerated by exposure to wind and sun. Nuglandin Cream, by making good the deficiency, restores to the skin the bloom of youth.”

I have not found any trace of Nuglandin being sold outside Britain and advertising for the products rapidly dropped off there after 1936.

See also: Hormone Creams, Oils and Serums

Sun-care

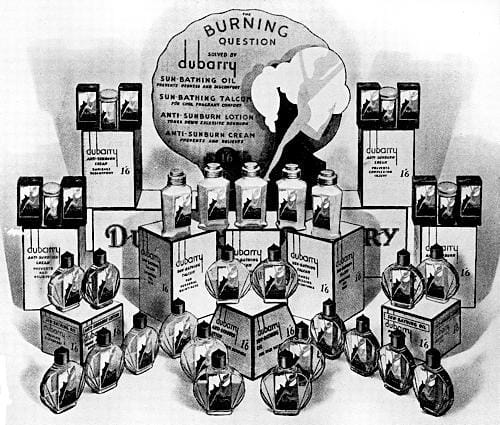

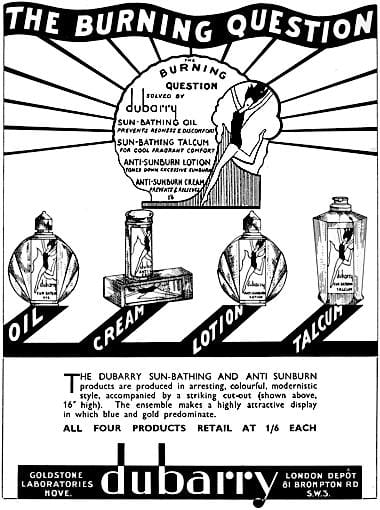

In 1934, Dubarry extended its sun-care range with Sun-Bathing Oil, Sun-Bathing Talcum, and Anti-Sunburn Lotion adding these to the Anti-Sunburn Cream it had introduced in 1927.

Above: 1934 Dubarry sun-bathing and anti-sunburn products all packaged in new containers.

Sun-Bathing Oil: “Prevents redness and discomfort.”

Sun-Bathing Talcum: “Fragrant and cooling when the skin is overheated.

Anti-Sunburn Lotion: “Soothes the skin when burnt. For evening use, tones down sunburn when applied to neck and arms.”

Like the earlier Anti-Sunburn Cream I have no information on their formulation but note that this is the only time I have seen a company advertise a talcum as a sun-care product.

Make-up

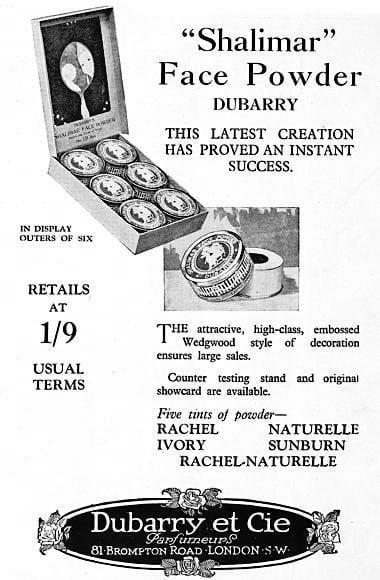

In 1930, Dubarry repackaged its Shalimar Face powder in new boxes with a Wedgwood-style embossed lid. It came in five shades – Rachel, Naturelle, Ivory, Sunburn, and Rachel-Naturelle.

Poudre Dubarry and Powdrettes were also still be made with the compact powder coming in a new square platinoid case in 1931. Dubarry added a green tinted shade to both products in 1931 but this was only available in one scent, Jasmine.

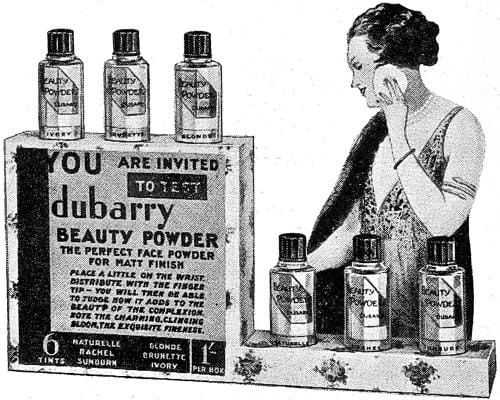

In 1933, Dubarry added Dubarry Beauty Powder packaged in a see-through, square box with a floral design in six shades – Naturelle, Rachel, Sunburn, Blonde, Brunette, and Ivory.

Above: 1933 Tester for Dubarry Beauty Powder.

The only other make-up product developed by Dubarry in the 1930s, that I know of was the Jack in the Box Lipstick, a slide up automatic in unknown shades.

War

Dubarry had some of its most profitable years during the Second World War thanks to a series of government contracts contracts for pharmaceuticals. Profits rose from £60,811 in 1941 to £104,310 in 1942, although they dropped back £35,654 in 1943 and £69,700 in 1944 Dubarry. Fortunately, the Goldstone factory in Hove escaped being bombed by the Germans.

Sales of cosmetics in Britain were dramatically affected by shortages in materials, restrictions and the introduction of the Purchase Tax introduced in October, 1940 which was levied on the wholesale value of luxury goods including cosmetics initially at 33.33%.

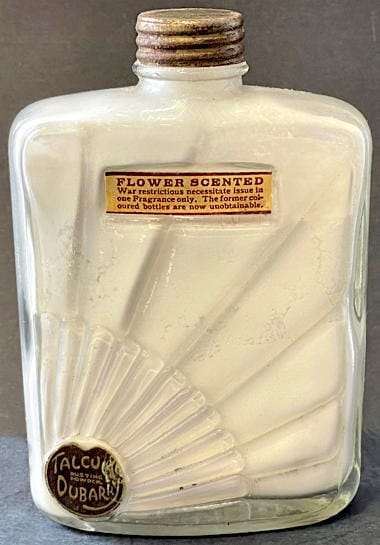

Dubarry continued to make cosmetics during the war but shortages forced it to make a number of changes. For example, Poudre Dubarry was put into wartime packaging and had its shade range reduced to New Naturelle, and New Rachel by 1942. Dubarry Talcum had its fragrances reduced to one and was packaged in a clear glass rather than the pre-war coloured containers.

Post war

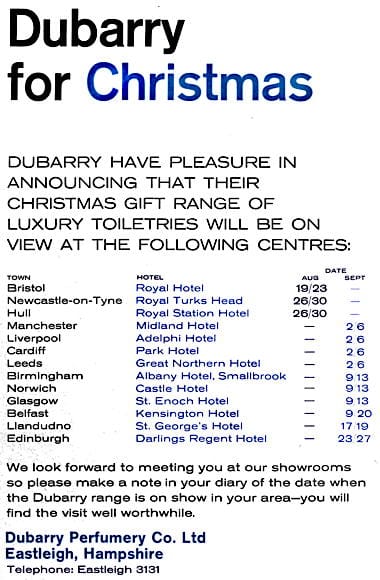

I have very little information on Dubarry’s cosmetic operations after the war through to the company’s sale in 1962. However, what is available does not paint a good picture. Having failed to establish an innovative skin-care or make-up range the company was left with Creme Shalimar, and bath products like Dubarry Talcum Powder as its main sellers with a heavy reliance on Christmas sales of coffrets.

Above: 1951 Crème Shalimar.

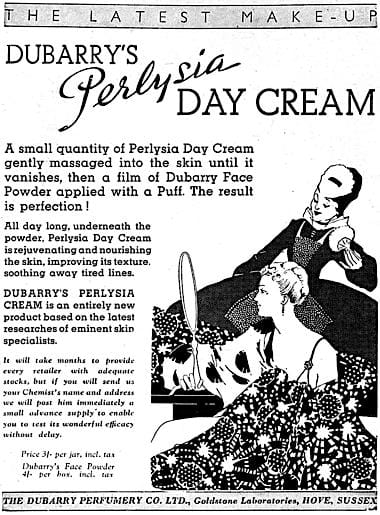

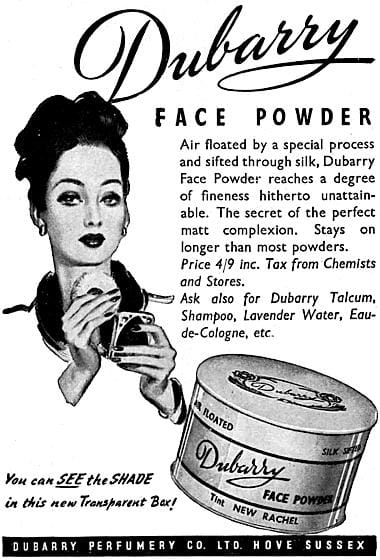

Dubarry Face Powder was only available in three shades after the war – New Naturelle, New Rachelle, and Blonde – packaged in a very inattractive box. In the 1950s, the box was replaced by one with embellished with a floral pattern but the shade range was still very limited – Apricot, Pastel, Peach, and Radiant. The face powder was to be applied over Dubarry’s new Perlysia Day Cream (1946). Dubarry had used this name before having sold a Perlysia Tooth Paste back in 1916.

Perlysia Day Cream: “All day long i]under the powder Perlysia Day Cream is rejuvenating and nourishing the skin, improving its texture, soothing away tired lines.”

Perlysia Day Cream is the only new cosmetic produced by Dubarry after the war that I know of, with the company continuing to rely on a few of its well-known and better selling lines.

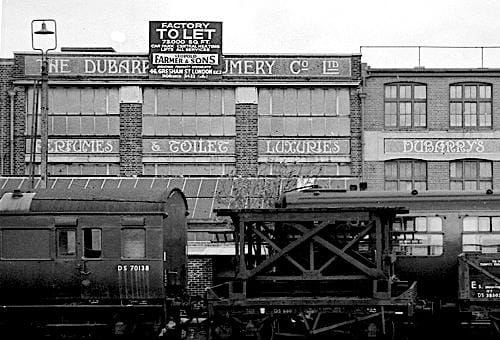

Sale

In 1962, Dubarry Perfumery was sold to William Warner & Co. Ltd. of England, a subsidiary of Warner-Lambert the owners of the other Du Barry, and the operations in Hove were quickly moved to Warner’s plant in Eastleigh, Hampshire.

Above: 1964 Hove factory up for rent.

Warner-Lambert looks to have been primarily interested in the Dubarry trademark. They sold off Dubarry Perfume’s pharmaceutical business to J.M. Loveridge Ltd. in 1963 and appear to have discontinued the British Dubarry range soon afterwards. The American Du Barry did not outlast it for very long with Warner-Lambert abandoning the brand in the 1970s.

Timeline

| 1901 | Standard Tablet Company established in Hove. |

| 1902 | Factory leased in Hove. |

| 1906 | Standard Tablet Co. becomes The Standard Tablet & Pill Co. |

| 1908 | Hove factory expanded. Pharmacy at 16 Western Road sold. |

| 1910 | The Standard Tablet and Pill Co. Ltd. established. |

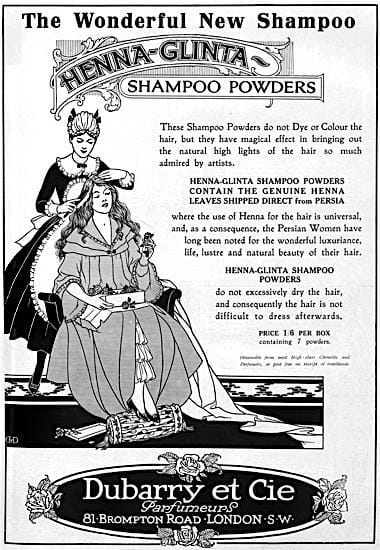

| 1916 | Dubarry et Cie founded. Shop opened at 81 Brompton Road, Knightsbridge. New Products: Dubarry perfumes, face powders, dusting powders, bath salts, bath crystals, soaps, and shampoo powders including Poudre Dubarry; Crème Shalimar; and Henna-Glinta Shampoo. |

| 1917 | Standard Tablet & Pill Co. Ltd. becomes the Standard Tablet & Co. Ltd. New Products: Dubarry Bath Salts; and Dusting Powder. |

| 1919 | New Products: Dubarry Powdrette. |

| 1921 | New Products: Debonair Shaving Milk. |

| 1922 | New Products: Dubarry Day Cream; and Dubarry Night Cream. |

| 1923 | Dubarry Perfumery Co. Ltd. established. |

| 1925 | New Products: Glinta Liquid Nail Polish. |

| 1926 | New Products: Peach Bloom. |

| 1928 | New Products: Eye-Lip Pencil. |

| 1930 | Hove factory expanded. New Products: Shalimar Hair Cream. |

| 1931 | New Products: Shalimar Wave-Setting Lotion; Shalimar Lemon Cleaning Cream; and Shalimar Orange Night Cream. |

| 1933 | New Products: Dubarry Beauty Powder; and Jack in the Box Lipstick. |

| 1936 | New Products: Nuglandin. |

| 1937 | Shop in Brompton Road closed. |

| 1938 | Quality Chemists Ltd. and Laking Chemical Co. Ltd. founded. |

| 1946 | New Products: Perlysia Day Cream. |

| 1962 | Dubarry bought by Warner-Lambert. |

| 1963 | Dubarry moved to Eastleigh, Hampshire. Standard Tablet sold to J.M. Loveridge Ltd. |

First Posted: 16th February 2024

Sources

Chapman, S. (1975). Jessie Boot of Boot the chemists: A study in business history. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

The chemist and druggist. (1859-) London: Morgan Brothers.

Cousins E. G. (1935) On the British sets Picturegoer Weekly, May 25.

Duncan, J. (2015). Dubarry Perfumery Co. Retrieved December 19, 2022, from http://compactcollectors.co.uk/

ARCHIVE/PDF/Dubarry%20Perfumery.pdf

Middleton, J. (2016). Dubarry Perfumery, Hove Park Villas. (revised 2021). Retrieved December 19, 2022, from http://hovehistory.blogspot.com/2016/01/

dubarry-perfumery-hove-park-villas.html

Dubarry Adverts (n.d.) Retrieved January 23, 2024, from https://www.gbstampbooklets.com/dubarry-adverts/

1901 Kilby Pears & Son.

1901 Standard Tablet Company.

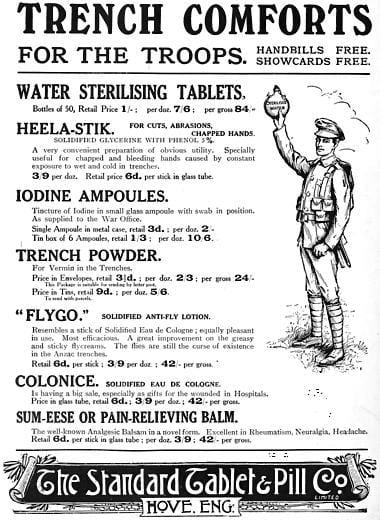

1915 Trade advert for The Standard Tablet & Pill.

1915 Trade advert for The Standard Tablet & Pill Company. Trench comforts that could be sent to loved ones on the front.

1916 Trade advert for Dubarry et Cie.

1916 Henna-Glinta shampoo powders.

1917 Dubarry Perfumes.

1917 Dubarry Compressed Bath Salts.

1918 Trade advert for The Standard Tablet & Pill Company for skin creams made without glycerine.

1918 Powdrette Dubarry.

1918 Dubarry Perfumes.

1919 Crème Shalimar hand cream, .Glinta Nail Polishing Paste, Hella-Stick for broken chilblains and frostbite, and Blainice for unbroken chilblains.

1919 Dubarry Toilet Soaps.

1919 Dubarry Creme Printaniere, Creme à la Glycerine, Creme Velysia, and Creme de Nuit.

1919 Dubarry Dusting Powder.

1923 Dubarry Golden Morn Series.

1924 Trade advert for Dubarry Silkashave Shaving Soap. It came in a range of fragrances including Lavender, Heather Scented, Oatmeal, Lemon, Verbena, Golden Morn, Santal, Rose d’Antan, Carnation, and Alpine Violets.

1925 Dubarry Toilet Luxuries.

1926 Trade advert for Dubarry Peach Bloom.

Dubarry Shalimar in one of a number of different bottles produced for this perfume. It created problems for Guerlain. He was forced to advertise his Shalimar perfume as Perfume No. 90 in places where Dubarry was sold, a situation that only changed after Warner-Lambert bought Dubarry in 1962.

1926 Dubarry Eye-Lip.

1926 Trade advert offering free line blocks for Cherry-Rip Lipstick, Lippax Lipstick, Iridessa Bath Soap, and Lavender Water.

1926 Dubarry Glinta Nail Polish.

1927 The pharmacy at 16 Western Road, Hove, now operated by F. C. Jackson.

1928 Dubarry Night Cream (Australia).

1928 Trade Advert for Dubarry Anti-Sunburn Cream and Colonice, an Eau de Cologne stick.

1930 Trade Advert for Shalimar Face Powder.

1931 Trade Advert for Dubarry Powdrette.

1932 Trade advert for Dubarry Perfumery. This image was reused to promote Perlysia Cream in 1946.

1932 Trade advert for Dubarry Shaving Soap.

1932 Trade advert for Dubarry Powdrettes.

1932 Trade advert for Dubarry Sportsman Series for men, many products in Duralite containers.

1933 Trade advert for Dubarry ‘Jack in the Box’ Lipstick, and the Dubarry Vanity Box.

1933 Trade advert for Dubarry Beauty Powder.

1934 Trade advert for Dubarry Sun-Bathing Oil, Sun-Bathing Talcum, Anti-Sunburn Lotion, and Anti-Sunburn Cream.

Shalimar Solid Brilliantine. It seems likely that the red has been rubbed off from a lot of the flowers.

Shalimar Lemon Cream. It is missing its metal base.

1935 Shalimar Orange Night Cream, Shalimar Lemon Cream, Shalimar Powder Cream, and Crème Shalimar.

1936 Dubarry Eau de Cologne.

1936 Dubarry Talcum Powder.

1936 Dubarry Nuglandin.

1939 Dubarry Crème Shalimar.

Dubarry Talcum in clear glass wartime packaging.

1944 Dubarry Face Powder in packaging that was being used by 1936.

1946 Dubarry Perlysia Day Cream.

1947 Dubarry Face Powder.

Dubarry Face Powder in post-war packaging.

1951 Trade advert for Dubarry Toilet Luxuries.

1963 Trade advert for Dubarry Perfumery now in Eastleigh, Hampshire.