Prince Matchabelli

Prince Georges Vasily Matchabelli was born in Tbilisi – formerly known as Tpilisi or Tiflis – the capital of Georgia. The Matchabelli (Machabeli) family had large estates in the Samachablo (literally ‘of Machabeli’) region of Inner Kartli (Shida Kartli) Georgia. Georges, who also described himself as being of Tamarasheni, received a general education at the Tbilisi College of Nobles, followed by engineering at the Frederick William University in Berlin – known today as the Humboldt University – before returning to Georgia to help with the family mining interests. In 1917, he married the Italian actress Norina Gilly [1880-1957] – stage name Maria Carmi – in Stockholm, Sweden.

When Georgia became a republic in 1918 – following the Russian Revolution of 1917 – Matchabelli offered his services to the new government and was made Minister Plenipotentiary to Italy. He moved to Rome in 1918 but the posting came to a close in 1921 when Georgia’s independence was ended by the invasion of the Red Army. To make matters worse the new Soviet government confiscated the Matchabelli estates and mining interests.

In 1923, Norina was engaged by the producer Morris Gest [1875-1942] to perform in an American revival of ‘The Miracle’ – a theatrical spectacular written by her first husband Karl Vollmöller [1878-1948] – repeating her London performance of 1912 and she moved to New York.

Above: Postcard of the London stage production of ‘The Miracle’ (Max Reinhardt, 1912) with Maria Carmi as the Madonna. She would marry Prince Matchabelli five years later and this play would bring them both to New York.

Georges followed Norina to New York from Italy in 1923. Although Norina terminated her contract with Gest in April, 1924 – and then began legal proceedings against him – the couple remained in New York and became involved in the city’s social and cultural life.

To help with their finances Norina did an endorsement for Pond’s creams in 1924 and Georges leased a store at 545 Madison Avenue from Douglas L. Elliman & Co. There he opened ‘Rouge et Noire’ (Red and Black), an antiques, gifts and imported novelties shop. Norina eventually patched things up with Gest and appeared in the 1929 Detroit production of ‘The Miracle’. By then Georges had moved on from antiques and was busy with a new venture, a perfume company.

Prince Matchabelli Perfumery Company

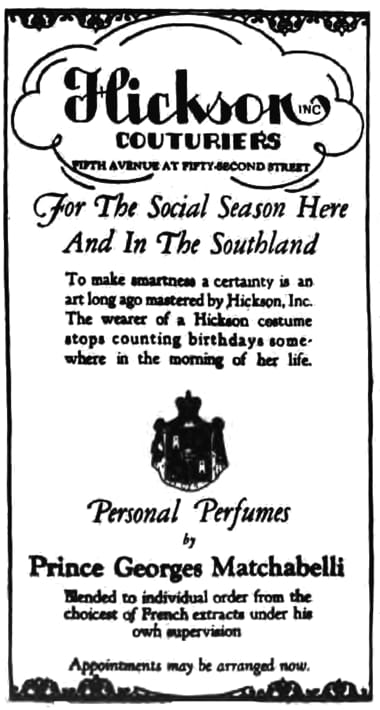

In 1926, Georges borrowed four thousand dollars and together with Norina established the Prince Matchabelli Perfumery Company. Operations began modestly with Georges making special perfumes in the basement of the Madison Avenue store for noted personalities such as Gloria Swanson [1899-1893] and Dolores Costello [1903-1979] as well as society women such as Mrs. William Randolph Hearst [1882-1974]. He also made personal appearances at Hickson’s in their Fifth Avenue store and others in various American cities either selling his own perfumes – Princess Norina and Ave Maria, named in honour of his wife and her role in ‘The Miracle’ – or blending fragrances individually for Hickson’s clients. In 1927, he began appearing on a perfume counter at Bergdorf-Goodman at 754 Fifth Avenue selling perfumes he was making in his laboratory on East 60th Street. Sales to other department stores followed.

The business expanded rapidly, helped along by the company’s association with royalty. Prince Matchabelli complemented his royal background by hiring other Georgian and Russian émigrés with connections to noble houses where possible.

Prince Matchabelli affects to be very particular where his perfume is marketed, and has refused to let several places handle it because he felt their social tone was not just right. Meeting a woman for the first time, he often politely informs her that her perfume is unbecoming and sends her one of his own. If she is still using her old kind the next time he sees her, he says, “You have not been faithful to me.” His business nets a quarter of a million a year, they say, and has grown out of its cellar to a laboratory in Fifty-sixth Street where sachets, powders, lipsticks, eye-shadows, and soap are made. He employs no salesmen. Every spring and fall he goes on the road himself. With his gardenia, his bows and courtly airs, and his visiting card with its embossed seal he creates an extraordinary impression on buyers who have never before trafficked with a genuine, hundred-per-cent prince.

(The New Yorker, 1930, p. 13)

According to numerous reports, Georges had a long-standing interest in perfumery which had begun in Berlin where he had blended perfumes for friends.

While studying in Berlin to be a mining engineer he became interested in perfumes through the plight of a lady friend who could not find the odor she desired. His chemistry professor, by advice and precept, enabled him to make the blend and he became interested in the science. On coming to America, where he opened an antique shop, he devoted his spare time to delving in the preparation of perfumes and found it both fascinating and more profitable than antiques. So he went on with the study of chemistry and odors, going into it thoroughly, as will be seen by the fact that for two years he has attended the night courses on perfumes and cosmetics conducted by Professor Wimmer at the New York College of Pharmacy, Columbia University (AP&EOR, 1927).

However, Matchabelli was not the only émigré to get into perfumes and the idea of establishing a perfume business may have come from his contacts in Paris. There, a number of Parisian fashion houses started by Russian émigrés had begun developing perfumes after Chanel introduced Chanel No. 5 in 1921. The list included: Prince Felix Felixovich Youssoupoff (Yusupov) [1887-1967] the co-founder of Irfé who began creating scents in 1926; Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna [1890-1958], the founder of Kitmir who introduced her fragrance ‘Prince Igor’ in 1928; and Baroness Elizabeth Hoyningen-Huene [1891-1973], the founder of the Yteb, who began making perfumes in 1929 (Vassiliev, 2000).

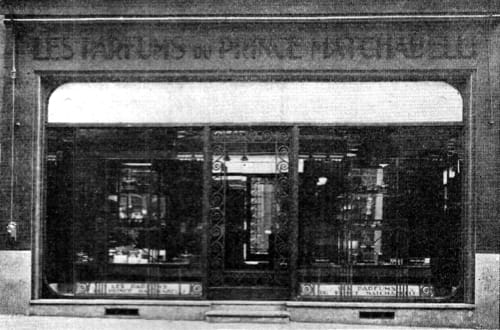

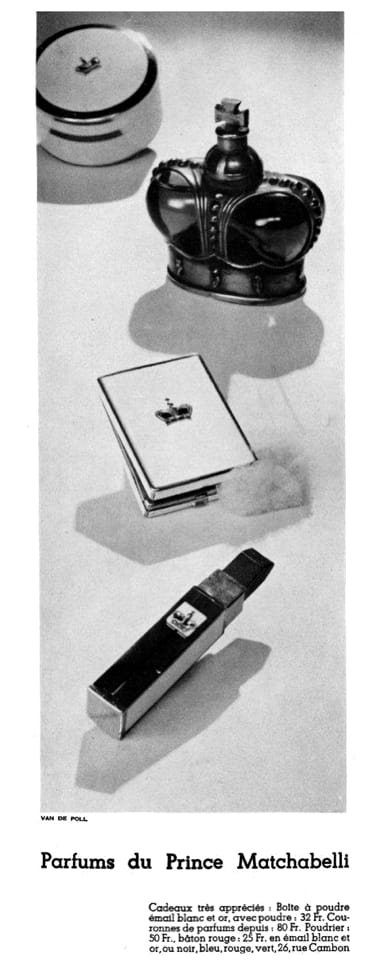

The growth of the Matchabelli company necessitated a series of moves, first to East 60th Street, then to 686 Lexington Avenue, and on to 160 East 56th Street in 1929. In 1929, Matchabelli founded Les Parfums du Prince Matchabelli S.A. (capital ₣1 million), established a Parisian factory at 58 Rue de Meudon, Clamant and opened a showroom in the Hotel George V at 31 Avenue George V, Paris. This luxury hotel, completed in 1928 by the American businessman Joel Hillman [1866-1951], catered primarily to wealthy American clients. It was probably recommended to Matchabelli by his press agent, Benjamin Sonnenberg [1901-1978], who had been working to promote the Hotel George V since 1926 (Cutlip, 1994, p. 340). Matchabelli would not stay there for long. In 1930, he opened new showrooms at 26 Rue Cambon, Paris, opposite Chanel.

Above: 1930 Les Parfums du Prince Matchabelli at 26 Rue Cambon. The predominant colour in the showrooms was brown with golden brown draperies and furnishings against a background of marble. Large display windows featured perfumes packaged in one colour made possible by the addition of a number of new perfume bottle colours in 1930.

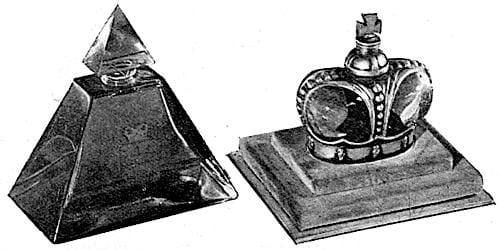

Above: 1931 Prince Matchabelli perfumes in Lalique bottles.

Additional European outlets were opened at Deauville, Cannes, Nice, Biarritz, Tokay, Basle, Zurich and Lucern with the European operations of Les Parfums du Prince Matchabelli being looked after by Jean Lestande de Villani. An agency was also established in London under the management of Prince Soumbatoff (AP&EOR; 1930), another Georgian expatriate.

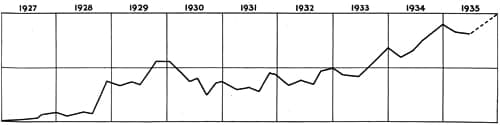

The Great Depression of the 1930s affected sales and may have been the reason behind the addition of new perfume bottle colours (blue, black, rose, etc.) in 1930, and the decision to begin selling perfume in smaller, cheaper, one and two dram sizes. These were more affordable and opened Matchabelli to a wider number of buyers. In 1935, Matchabelli also boosted sales by advertising in newspapers for the first time on its own right. Previously this had only been done in cooperation with department stores and other dealers.

Above: 1935 Chart of sales of Prince Matchabelli Perfumery, Inc. from 1927 to 1935 (D&CI, 1935, p. 201).

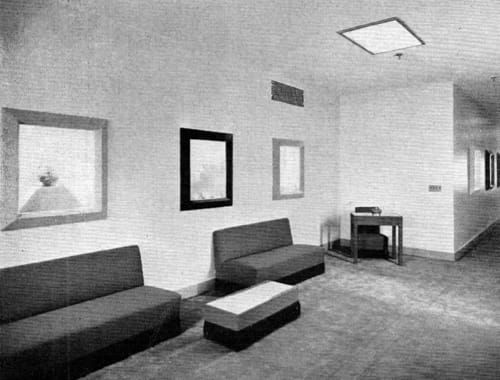

In June, 1935, a new Matchabelli showroom was opened on the eleventh floor of the former National Broadcasting Building at 711 Fifth Avenue, New York. Occupying almost 1,700 square metres (18,000 square feet) it included space for offices, manufacturing facilities and showrooms. Unfortunately, Georges Matchabelli was not there to see it, having died from pneumonia at the end of March.

Above: 1935 The Matchabelli entrance hall at 711 Fifth Avenue, New York designed by Cecil Beaton [1904-1980] using a mixture of modernist, Victorian and Russian decorative elements. Product showcases framed in yellow, blue, green, purple, black and red velvet were built into the grey coloured walls. The floor was carpeted in scarlet while the couches and tables were covered in purple felt, edged with black fringing. Lighting fixtures were made as crowns like those used in the Matchabelli bottles. At the end of the corridor was a Spanish street scene painted by Pavel Tchelitchew [1898-1957].

Cosmetics

Prince Matchabelli is best known for its perfumes and colognes but the company began selling cosmetics soon after it was established. There are some suggestions that early products included a skin lotion but, in general, most cosmetic lines were associated with bathing or were a type of make-up.

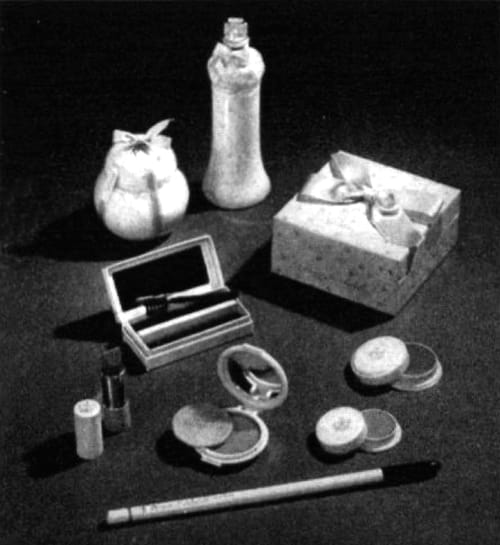

Belila, a liquid whitener for the arms and shoulders, and Bronzina, a red liquid that turned beige on application to give the skin a tanned appearance, were both introduced in 1929. By then Matchabelli was also selling lipsticks; triple, double and single compacts in attractive black containers with a gold crown on them; soaps; face powders; and a pine essence for the bath. It seems very unlikely that Matchabelli was making most of these lines but rather was assembling, packing and distributing items manufactured by private label firms. Product packaging was extremely important to the success of the business and a great deal of attention was given over to it. Other colour cosmetics such as mascara and eyeshadow were added soon after.

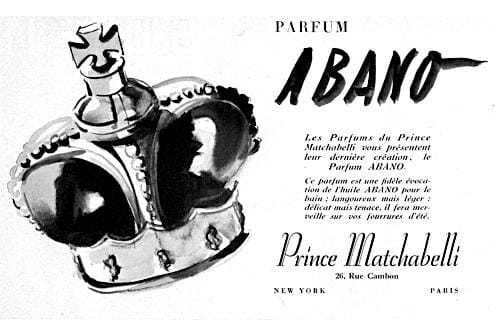

In regard to cosmetics, two early Matchabelli perfumes are worth mentioning. The first was Duchess of New York (1929) which outsold all other Matchabelli fragrances in the early 1930s by a wide margin (Stone, 1935, p. 201) and was later used as the basis for a make-up line; the second Abano (1931) became the basis for a number of lines.

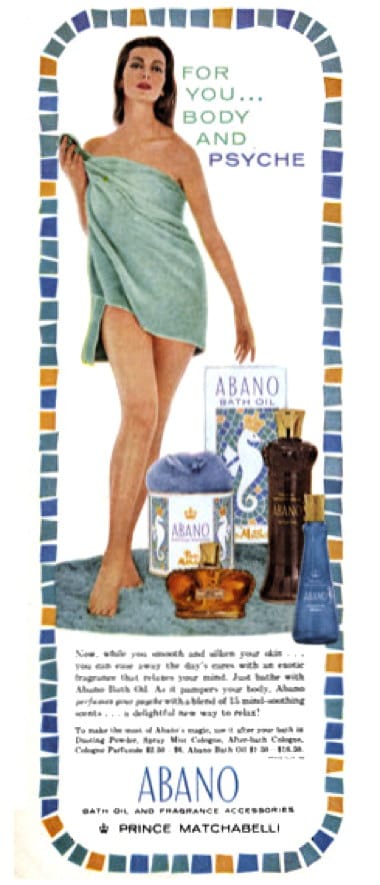

Abano

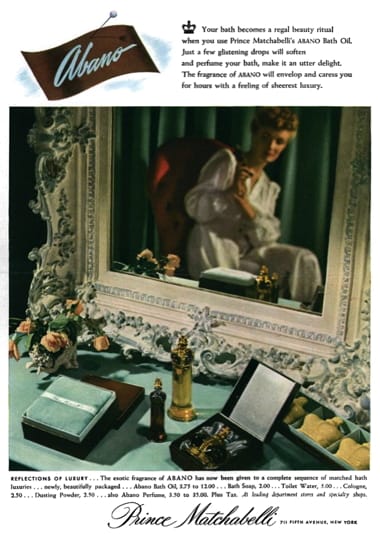

Created originally as a perfume, Abano is best known for Abano Bath Oil (1932), a popular product that predated Estée Lauder’s Youth Dew Bath Oil by two decades.

Above: 1936 Matchabelli Albano Perfume (France).

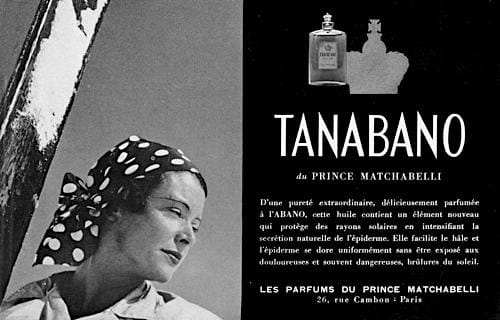

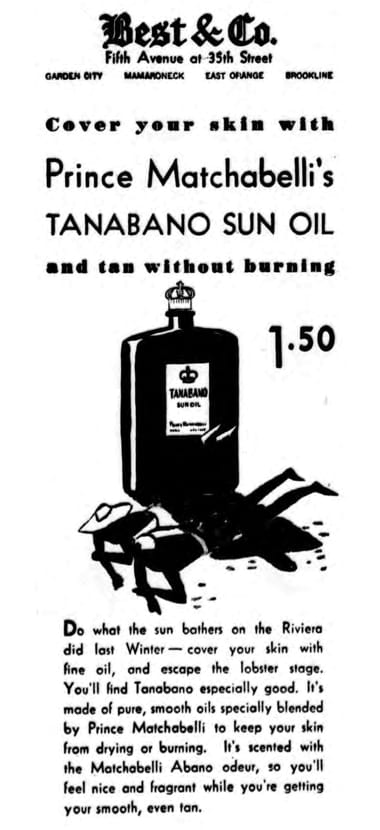

Matchabelli also used Abano as the fragrance for Tanabano (1933), a sun oil, and successive owners of the firm added other lines including Abano Dusting Powder, Abano Cologne Sticks (1950), Abano After Bath Cologne (1954), Abano Spray Mist Cologne, and Abano Dry Skin Treatment Bath Oil (1961).

Above: 1935 Matchabelli Marine Bag containing a lipstick, compacts, a comb, and a bottle of Tanabano Sun Oil.

Above: 1936 Matchabelli Tanabano Sun Oil (France).

See also: Estée Lauder

New owners

In 1935, Georges succumbed to pneumonia in his apartment at 320 East 57th Street. Norina was at his bedside when he died, despite having divorced him in 1933. After Georges’ death the presidency of Matchabelli passed to her and the company was put into administration. Georges owned about 60% of the American business and also had some shares in the French branch. Beneficiaries of his estate – made up of cash, shares and some mortgaged French real estate – included: Ilo Vasilievich Matchabelli, a brother residing in Leningrad;Nina Dvingaradze, a sister living in Paris; and Thamar Matchabelli, a niece also from Paris. Most of the inheritance was to go to Ilo Matchabelli but Norina put in a claim for US$30,000 and one-third of the estate (New York Post, April 30, 1935).

James F. Egan, the Public Administrator for New York County at the time, petitioned to have the company put up for sale. The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review (1936) states that Matchabelli was acquired by D. Lizner & Co. and Parfums Weil, Paris which suggests that the American and European interests were split and sold separately. This seems unlikely as Vick Chemical – a later owner of Prince Matchabelli – promoted the reunification of the French and American parts of Matchabelli after the Second World War and I can find no records of Vick having separately purchased the French branch after they acquired Prince Matchabelli in 1941.

D. Lizner & Co., was controlled by Saul Ganz [1874-1953] and he installed his son Paul H. Ganz [1910-1986] as president of the company. As far as I can tell little of interest was done with Matchabelli or its products before it was sold to the Vick Chemical Company in 1941. A 1936, U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) decision stopped Matchabelli from using the words ‘26 Rue Cambon, Paris’ or any similar terms that would give the impression that its products were imported. This suggests that all the American Matchabelli products were made locally.

Vick Chemical Company

As well as Prince Matchabelli, Inc., the Vick Chemical Company also bought the Alfred D. McKelvy Company, makers of the Seaforth range of men’s toiletries that had been started by Alfred D. McKelvy [1901-1984] in 1939.

See also: Alfred D. McKelvy (Seaforth)

Both companies were kept as separate subsidiaries as part of the Vick’s decentralisation policy. Alfred D. McKelvy stayed on as the head of Alfred D. McKelvy while Norman F. Dahl [1896-1979] was made president of Prince Matchabelli.

Above: 1946 Cyril Gurge, the chief perfume chemist at the Prince Matchabelli laboratories. He was a life-long friend of Georges having been to school with him in Tbilisi. It is likely that he was working for Prince Matchabelli before the company was bought by Vick.

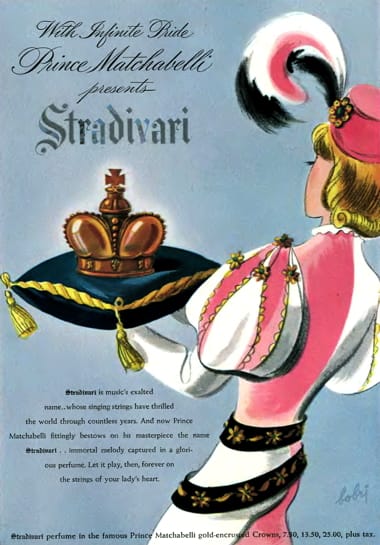

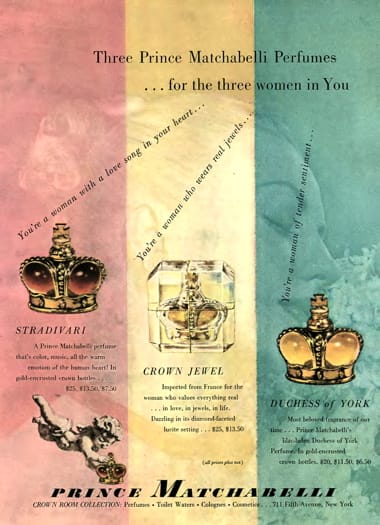

By 1945, Vick had increased Matchabelli sales by over 400% due in part to the introduction of Stradivari perfume (1942) which rapidly became Matchabelli’s top seller. Stradivari was promoted through radio broadcasts of the Stradivari Orchestra, a 15-piece ensemble created by Matchabelli which included eight genuine Stradivari violins, rented mostly from the Rembert Wurlitzer and Emil Herrmann collections (AP&EOR, 1947, p. 342).

Above: 1946 The Stradivari Orchestra, here conducted by Paul Lavalle, did regular radio broadcasts promoting Prince Matchabelli.

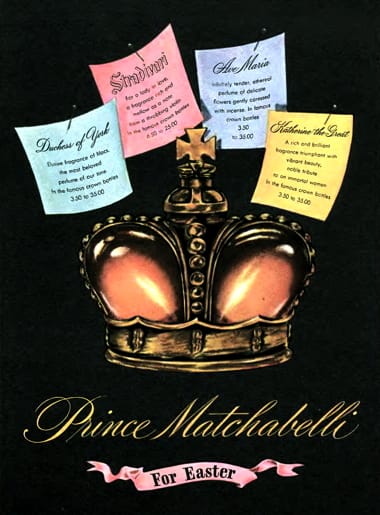

Duchess of York

In 1944, Matchabelli introduced a line of ‘echo tone’ make-up consisting of lipsticks (8 shades), face powder, rouge, mascara, eyeshadow (7 shades) and foundation (cream and liquid in 5 shades) all perfumed with Duchess of York, the idea being that each tone of make-up echoed the tones of the other, i.e., they were colour coordinated.

Above: 1946 Duchess of York make-up introduced in 1944. Packaging was given a great deal of attention. The small pots of cream foundation were made with ceramic rather than glass or plastic and were embellished with ribbon tied up by hand.

Post-war

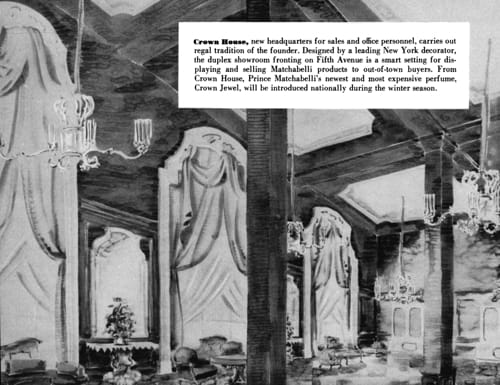

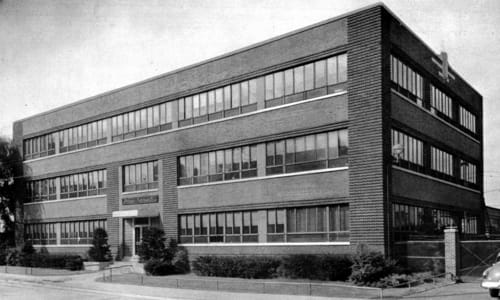

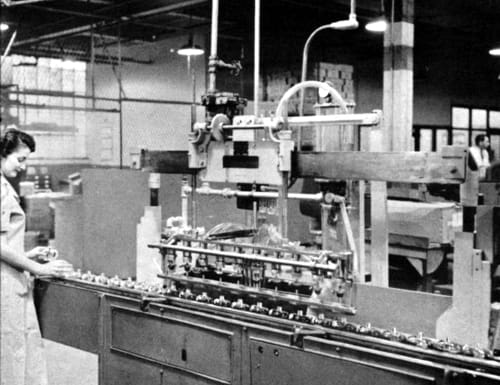

In 1946, the company celebrated two major events: the opening of the Crown Room – made possible by moving all manufacturing and research to Bloomfield, New Jersey – and the reintegration of the French and American arms of Matchabelli that had been separated by the German invasion of France during the Second World War.

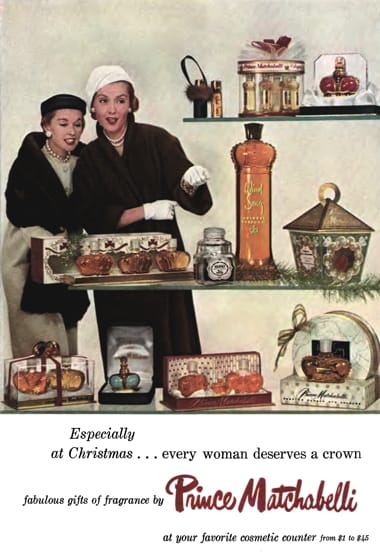

The Crown Room, designed by William Pahlmann [1900-1987], was situated on the second floor of 711 Fifth Avenue. Decorated in ‘regal swank’ the lavish design made good use of the two-story windows facing Fifth Avenue by having stained glass Matchabelli crowns inserted into them. Three balconies that overlooked the room contained displays of Matchabelli products. The company’s executive offices were also moved to the second floor.

Above: 1946 Drawing of the Crown Room.

After the initial opening, the Crown Room was used for other events including charitable functions for which the company provided the room free of charge.

Above: 1947 Second World War veterans stage an impromptu show at the Purple Heart Party in the Crown Room.

To celebrate the opening of the Crown Room a new perfume called Crown Jewel was launched. To generate publicity for it Princess Margarita Matchabelli – the sister-in-law of Prince Georges Matchabelli – was flown to New York carrying a bottle of the new fragrance.

Above: 1946 Princess Margarita Matchabelli, described as the head of the Paris Company, lunches with Norman F. Dahl, president of Prince Matchabelli, Inc.

Other notable Matchabelli perfumes introduced by Vick included Incanto, Beloved, and Wind Song.

The period after the war was not without its problems. The continuation of 20% excise tax on cosmetics and toiletries, instigated by the United States Federal Government during the war, depressed demand, and there were still shortages of raw materials and packaging. One way to reduce costs was to rationalise parts of the business. In 1949, the Seaforth and Matchabelli sales forces were amalgamated and Vick combined the two companies into the Matchabelli-Seaforth Division in 1956.

Above: 1955 Manufacturing facilities at Bloomfield, New Jersey where Matchabelli and Seaforth products were made. Production of Sofskin was also moved here when Vick bought the Sofskin Company in 1946.

Above: 1955 Filling bottles of Prince Matchabelli perfume at the Bloomfield factory.

Above: 1955 Summer Shower fragrance line consisting of cologne, bath salts, deodorant, soap and bath powder. Matchabelli produced a number of similar product lines each based on a different fragrance.

Competition in the cosmetic market increased during the 1950s and advertising expenses rose as greater use was made of television. Vick Chemical’s response to this new economic environment was to focus on drugs, chemicals and plastics where it was experiencing large increases in sales. Consequently, it sold its entire cosmetics business, which was showing little or no growth, to Chesebrough-Pond’s for cash in October, 1958.

Chesebrough-Pond’s

Chesebrough-Pond’s was well represented in many categories of cosmetics through its Pond’s creams and lotions and Angel Face make-up but the company lacked a prestige product line and was weak in perfumes and men’s toiletries.

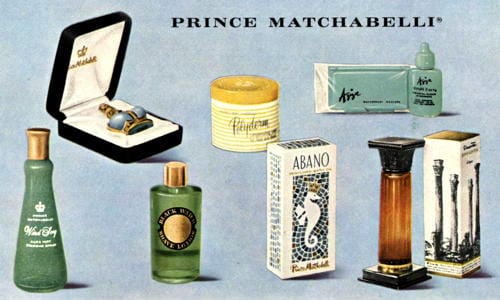

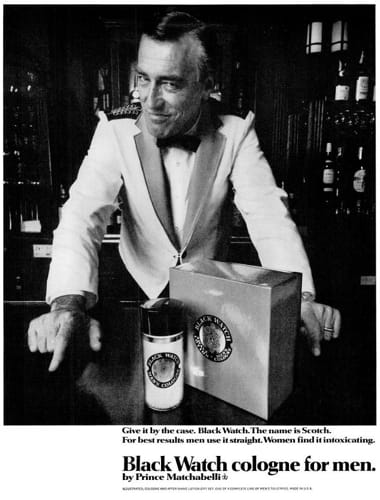

Above: 1959 Products marketed by Chesebrough-Pond’s Prince Matchabelli subsidiary: Wind Song Aqua Mist Cologne Spray, Prince Matchabelli Perfume, Black Watch Shave Lotion, Polyderm Compensating Cream, Abano Bath Oil, Aziza Waterproof Mascara and Simonetta Incanto Cologne.

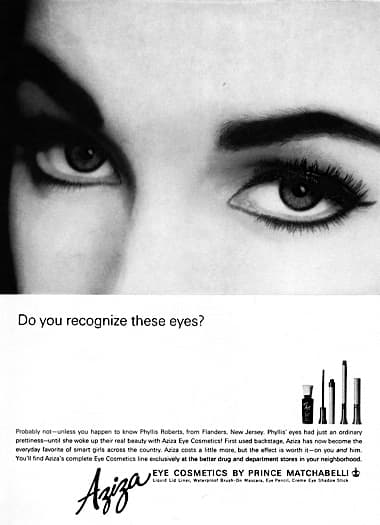

After the purchase of Prince Matchabelli, McKelvy (Seaforth and Black Watch), Polyderm and Sofskin from Vick Chemical, Chesebrough-Pond’s bought the Aziza Eye Cosmetics Division of Mauvel Ltd. in 1959. Then, in 1961, it combined Matchabelli, Black Watch, Polyderm and Aziza into a new Prince Matchabelli Division and sold off the Seaforth part of McKelvy to Mary Chess in 1962. In 1966, it added the Erno Laszlo Institute to the Matchabelli prestige group and followed this with Royall Lyme Ltd., makers of men’s toiletries, in 1967.

Chesebrough-Pond’s already had an extensive skin-care collection in its range of Pond’s skin creams and lotions so had no need for Sofskin and disposed of the line two months after it bought it. However, it retained Polyderm to give Prince Matchabelli an entry into the skin-care market.

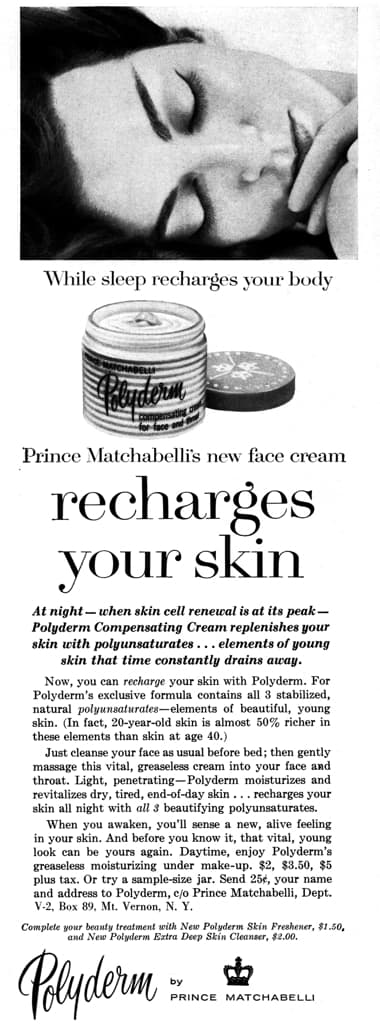

Polyderm

Polyderm had began its life in 1955 as Polyderm-20, a cosmetic skin specialty developed by Vick Chemical containing polyunsaturated fatty esters. Designed for women who were dieting or had abnormally dry skin, Vick put it through extensive marketing and clinical trials before releasing it in 1957. Chesebrough-Pond’s continued to promote it as a Matchabelli product after they acquired it.

Normal, healthy 21-year-old skin is almost twice as abundant in vital polylipids as skin at 40. As you grow older, these polylipids drain away, and a skin becomes dry, unsightly wrinkles, lines and crows feet begin to appear.

Now Polyderm returns polylipids to your skin, letting these vital, natural nutrients penetrate deep down into skin tissue … helping stimulate sluggish cells to expand … to absorb and hold moisture. In just a few days, taut dryness can disappear, old-looking lines and wrinkles begin to vanish.(Matchabelli advertisement, 1958)

After renaming it as Polyderm Compensating Cream in the 1960s, Chesebrough-Pond’s went on to create a Polyderm product range which included: Polyderm Moisturising Lotion (1961), a liquid form of Polyderm Compensating Cream; Polyderm Cleansing Cream; Polyderm Skin Freshener (1959), an astringent; Polyderm Medicated Skin Freshener (1963), which may have contained hexachlorophene; and Polyderm Bath Oil (1964), in capsules.

Chesebrough-Pond’s also added a number of new perfumes and colognes to its Matchabelli division – the most notable being Cachet, Wind Song, and Aviance – but there is little else of interest that can be said regarding Matchabelli cosmetics. Chesebrough-Pond’s important developments in skin-care and make-up were with its Pond’s and Angel Face ranges. The Prince Matchabelli Division concentrated on perfumes, colognes, and toilet waters and related products.

See also: Chesebrough-Pond’s

Later owners

Unilever acquired the Matchabelli group of products when it bought Chesebrough-Pond’s in 1986 but sold the Matchabelli fragrances to Parfums de Coeur Ltd. in Stamford, Connecticut in 1993. In 2012, Parfums de Coeur was acquired by Yellow Wood Partners, a private equity firm, who renamed Parfums de Coeur as PDC Brands in 2015. There is no mention of Prince Matchabelli in the current inventory of PDC Brands which suggests that the line has been abandoned.

Timeline

| 1926 | Prince Matchabelli Perfumery Company established. Prince Matchabelli makes personal appearances at Hickson’s. |

| 1927 | Prince Matchabelli opens a perfume counter at Bergdorf-Goodman, New York. |

| 1929 | New York headquarters moves to larger premises at 160 East 56th Street from 686 Lexington Avenue. Les Parfums du Prince Matchabelli S.A established in France. Paris factory opened 58 Rue de Meudon, Clamant. Paris showroom opened in the Hotel George V. Paris. New Products: Duchess of York perfume; Belila, liquid whitener; and Bronzina, liquid tan. |

| 1930 | New showroom opens at 26 Rue Cambon, Paris. Matchabelli agency established in London. New perfume bottle colours added. New Products: Pine Needle Soap. |

| 1931 | New Products: Abano Perfume; and loose powder compact. |

| 1932 | New Products: Abano Bath Oil. |

| 1933 | New Products: Tanabano, a sun oil. |

| 1935 | New New York headquarters and showrooms opened at 711 Fifth Avenue. |

| 1936 | Prince Matchabelli sold to D. Lizner & Co. |

| 1941 | Prince Matchabelli sold to the Vick Chemical Company. |

| 1941 | New Products: Stradivari perfume. |

| 1944 | New Products: Duchess of York make-up line. |

| 1946 | Crown Room opened. Manufacturing and research facilities for Matchabelli and McKelvy (Seaforth) moved to Bloomfield, NJ. New Products: Crown Room perfume. |

| 1949 | McKelvy and Matchabelli sales forces combined. New Products: Golden Crownstick lipstick. |

| 1952 | New Products: Extra Deep Skin Cleanser; Liquid Make-up; and Summer Showers cologne. |

| 1954 | New Products: Albano cologne. |

| 1956 | Matchabelli-Seaforth Division created at 415 Madison Avenue, New York. |

| 1957 | New Products: Polyderm. |

| 1958 | Prince Matchabelli bought by Chesebrough-Pond’s. |

| 1959 | New Products: Polyderm Skin Freshener. |

| 1961 | Chesebrough-Pond’s creates the Prince Matchabelli Division (Matchabelli, Black Watch, Aziza, Polyderm). New Products: Polyderm Moisturising Lotion; Abano Dry Skin Treatment Bath Oil; and Tact, a stick deodorant/antiperspirant. |

| 1963 | New Products: Polyderm Medicated Skin Freshener. |

| 1964 | New Products: Polyderm Bath Oil. |

| 1966 | Erno Laszlo Institute added to the Prince Matchabelli Division. |

| 1967 | Royall Lyme Ltd. added to the Prince Matchabelli Division. |

| 1974 | Prince Matchabelli creates a sales force to service specialty stores. |

| 1976 | Prince Matchabelli manufacturing relocated to Huntsville, Alabama. |

| 1986 | Chesebrough-Pond’s acquired by Unilever N.V. |

| 1993 | Prince Matchabelli sold to Parfums de Coeur Ltd. |

First Posted: 15th December 2015

Last Update: 1st March 2024

Sources

Chesebrough-Pond’s, Inc. Annual Reports 1955-1978.

Cutlip, S. M. (1994). The unseen power: Public relations: A history. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Stone, E. M. (1935). The rise of Matchabelli. The Drug and Cosmetic Industry. 37(2), August, pp. 201, 227.

The story of Prince Matchabelli. (1947). The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review. October, pp. 341-343.

Vassiliev, A. (2000). Beauty in exile: The artists, models, and nobility who fled the Russian revolution and influenced the world of fashion. (A. W. Bouis & A Kucharev, Trans.). New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Vick Chemical Company, Inc. Annual Reports 1941-1957.

Prince Georges Vasily Matchabelli [1885-1935].

1925 Rouge et Noire Exhibition.

1927 Prince Matchabelli at Hickson, Inc. Couturiers

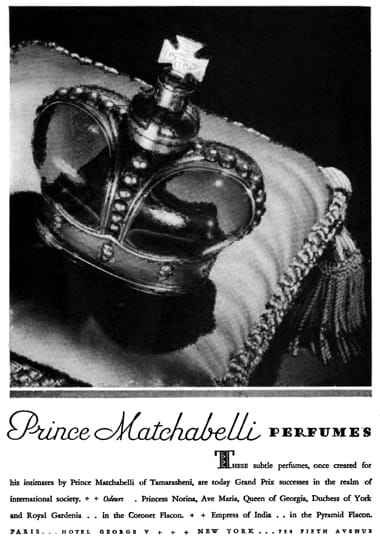

1929 Prince Matchabelli Perfumes. The early ‘Coronet Flacon’ bottles were made by the Coby Glass Products Company owned by another Georgian émigré George Coby (Grigol Kobakhidze) [1883-1967]. New bottle colours were added in 1930. Matchabelli was importing bottles in 1931 after George Coby went bankrupt following the stock market crash of 1929.

1932 Matchabelli Dusting Powder.

1933 Prince Matchabelli Tanabano. The sun tan oil came in a bright blue bottle so that it was highly visible in the sand and had a shaker-top that made it easy to apply.

The National Broadcasting Building at 711 Fifth Avenue designed by the architect Floyd de L. Brown [1885-1955] as photographed in 1925. Later known as the Columbia Pictures Building and the Coca-Cola Building. Matchabelli occupied the 11th floor of this building in 1935 but moved down to the second floor with its large windows when the Crown Room was opened in 1946.

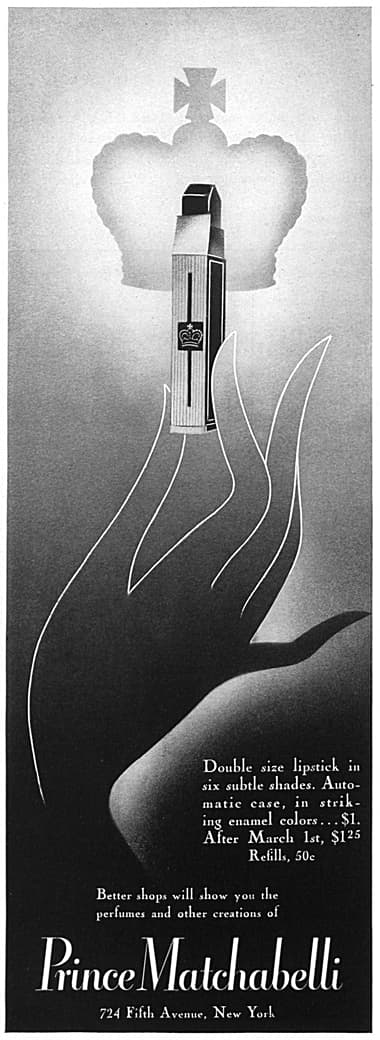

1935 Matchabelli Double Lipstick.

1936 Parfums du Prince Matchabelli (France).

1942 Matchabelli Stradivari perfume.

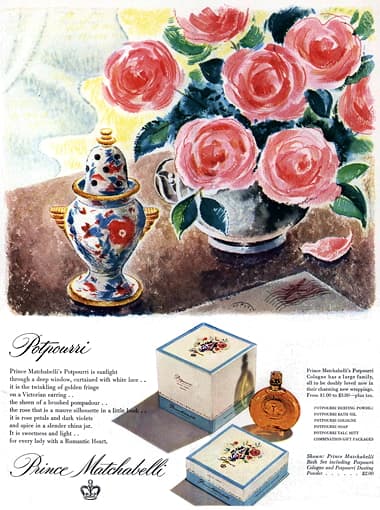

1942 Matchabelli Potpurri.

1943 Matchabelli Albano.

1944 Duchess of York Lipstick, Face Powder, Foundation Cream, Foundation Lotion, Cream Rouge, Rouge Compact and Eye Shadow.

1945 Prince Matchabelli Perfumes: Duchess of York, Stradivari, Ave Maria and Katherine the Great.

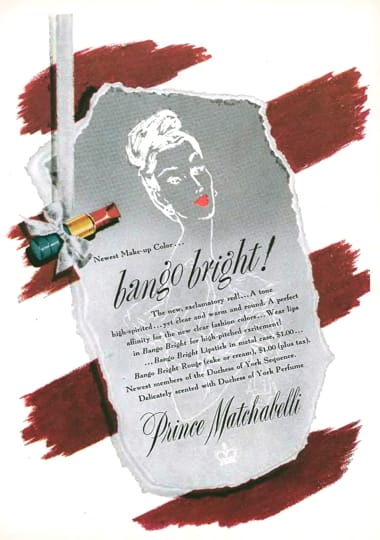

1945 Tango Bright shade of lipstick and rouge from the Duchess of York make-up range.

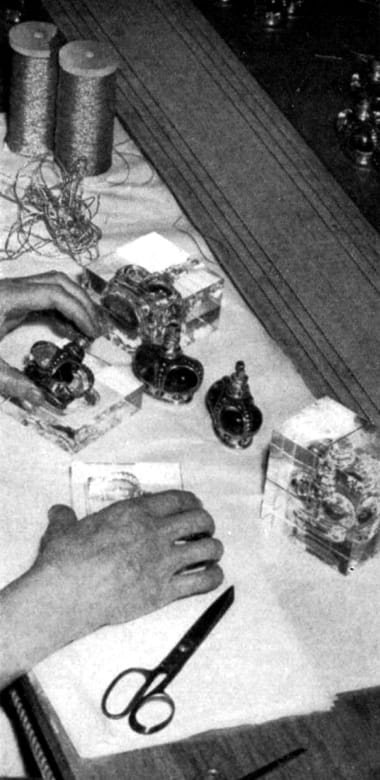

1946 Princess Margarita Matchabelli (right), wearing an orchid named after her, with Mrs. Pamela Churchill (left), the former daughter-in-law of Winston Churchill holding a bottle of Matchabelli Crown Jewel perfume. The publicity associated with this photograph suggests that Princess Matchabelli was introducing this perfume into America from Paris. Given the complexity of the packaging – the perfume bottle was encased in a prism of lucite – it seems unlikely that the bottle was made in postwar France.

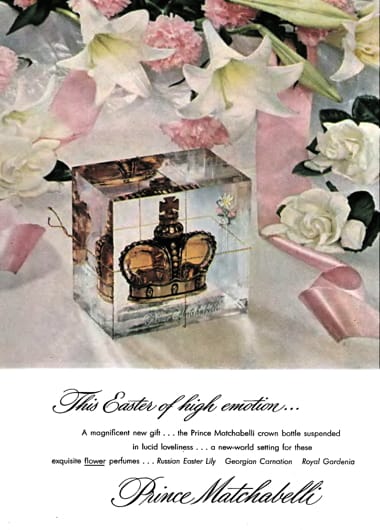

1946 Prince Matchabelli Perfumes: Russian Easter Lily, Georgian Coronation and Royal Gardenia.

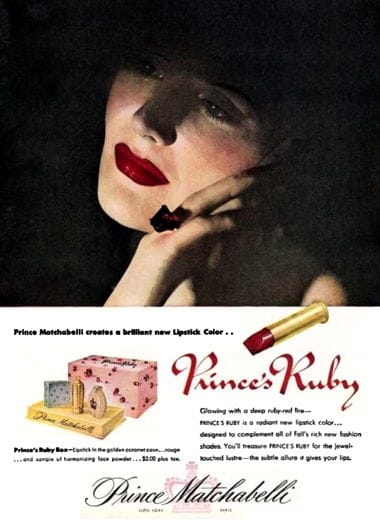

1946 Prince Matchabelli Prince’s Ruby Lipstick.

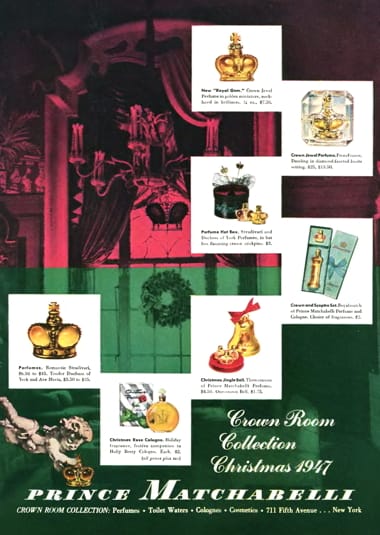

1947 Assembling Crown Jewel perfume bottles encased in polished lucite prisms, tied with gold cord, then wrapped and sealed by hand.

1947 Prince Matchabelli Perfumes: Stradivari, Crown Jewel and Duchess of York. The Crown Jewel container differs from the earlier version and was made of glass, manufactured by Kimble Glass, Toledo, Ohio.

1947 Prince Matchabelli Crown Room Collection.

1949 Golden Crownstick Lipsticks. The new swivel lipstick cases were topped with a Matchabelli crown.

1956 Prince Matchabelli.

1958 Prince Matchabelli.

1960 Prince Matchabelli Abano Bath Oil and accessories.

1960 Polyderm.

1964 Aziza eye cosmetics by Prince Matchabelli.

1966 Black Watch Cologne by Prince Matchabelli.

1981 Matchabelli: A distinctive man’s cologne. Chesebrough-Pond’s tries to ‘man-up’ the prince.