Hexachlorophene

In 1937, Burton T. Bush, Inc., the New York affiliate of Givaudan-Delawanna, began a research project to develop new antiseptic compounds. Headed by Dr. William S. Gump [1897-1986], the research team identified a number of promising halogenated phenols they called the G series. G-11 in the series – hydroxy-hexachloro-diphenyl-methane – proved to be promising and was later given the name hexachlorophene.

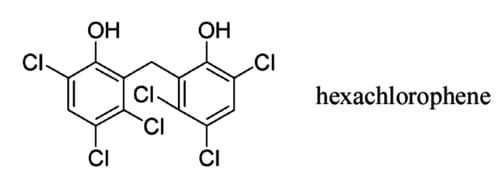

Above: The chemical structure of hexachlorophene.

Gump outlined the properties of this new compound in his 1939 patent application, granted in 1941.

This compound exhibits strong antiseptic and disinfecting action against micro-organisms and particularly against bacteria of the type of Staphylococcus aureus. It is also very effective as a fungicide. …

This new phenol is a white, practically odorless and tasteless solid compound. These qualities and physical properties permit its wide use as an antiseptic, bactericidal, fungicidal and preserving agent. It may be employed in solid form as well as in solution or emulsion or in admixtures with other active or inert substances such as tooth powders, toothpastes, ointments, creams, cosmetics, rubbergoods, etc.(Patent: US2,250,480, 1941)

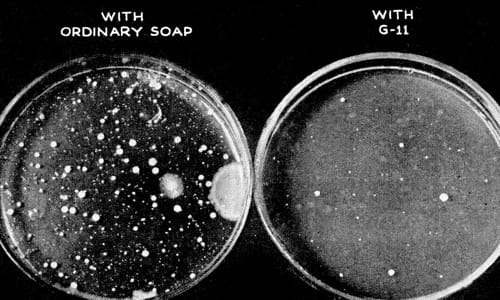

Above: 1945 Cultures taken to show the effectiveness of hexachlorophene (Popular Science, 1945, p. 83).

As well as being effective against bacteria and fungi, hexachlorophene did not have the strong odour associated with traditional phenol antiseptics. Gump suggested it could be used in a wide range of products including soaps.

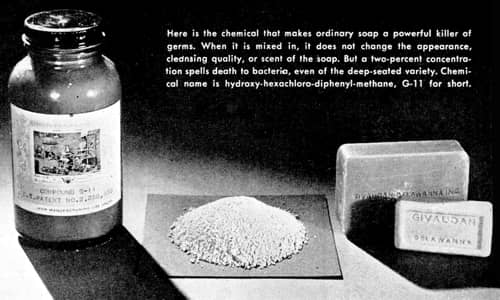

Above: 1945 Experimental soap bars made by Givaudan-Delawanna containing 2% hexachlorophene (Popular Science, 1945, p. 83).

Dial soap

In 1946, Armour & Company began looking into the possibility of developing a new deodorant soap. Deodorant soaps already on the market – such as Lifebuoy – typically used derivatives of cresol and had a strong medicinal smell (Seitz & Richardson, 1988, p. 345).

Above: 1934 Lifebuoy soap. In 1926, Lever Brothers began marketing Lifebuoy soap as a deodorant rather than a health soap and its sales quadrupled between 1926 and 1930 (Spitz, 2004, p. 26). First manufactured by Lever Brothers in 1887, it contained carbolic acid – the disinfecting agent used by the British surgeon Joseph Lister [1827-1912] – that had a strong, tar-like scent that was off-putting to many people.

Robert E. Casely, a research chemist at Amour, conducted experiments with a range of chemicals and after working his way down a list of possibilities without success, eventually tried hexachlorophene, testing its deodorising capabilities using small cotton pads to absorb odour in his armpits (Seitz & Richardson, 1988, p. 355). Hexachlorophene worked well as a deodorant, had a low level of skin irritancy, remained effective when incorporated into soap, and had a mild odour that was easily covered with scent.

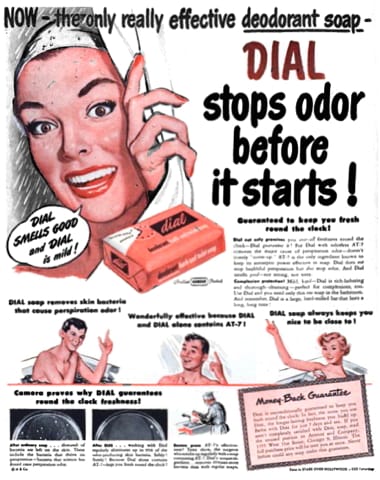

In 1948, Amour then launched a new soap containing hexachlorophene under the brand name ‘Dial’ and promoted it with a large advertising budget. By 1951, sales of Dial had passed Lifebuoy and it went on to become the top-selling soap in the United States in dollar volume by 1954. Lever Brothers got the message and made Lifebuoy more pleasant smelling; changing its germicide to tetramethylthiuram disulfide (TMTD) in 1953 (Spitz, 2004, p. 36).

Above: 1951 The Clean Look sponsored by Amour, the makers of Dial, with scenes on cleansing with Dial soap, applying make-up, deportment and hair-care.

Hexachlorophene and cosmetics

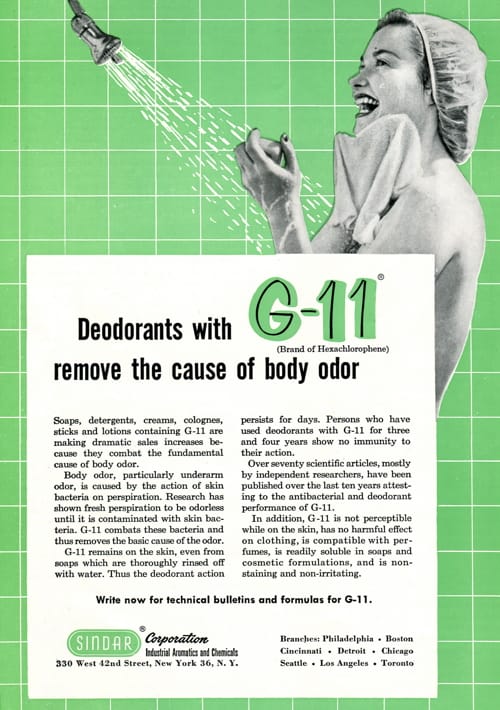

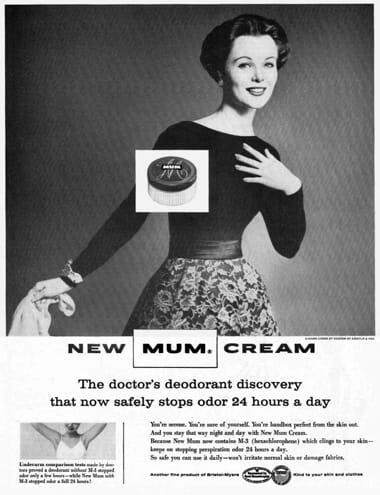

The success of Dial led to hexachlorophene – also advertised as G-11, AT-7, K-34, M-3, PC-11, HCP and others – being used as an antiseptic in a wide range of products including surgical scrubs, cosmetics, toothpastes, mouthwashes, anti-dandruff shampoos, general deodorants and feminine deodorant sprays. It was commonly employed in many more as a general preservative.

Above: Gilette Brushless Shaving Cream containing the facial antiseptic K-34 (hexachlorophene) Gilette began using hexachlorophene in their shaving creams in 1948.

See also: Deodorants and Antiperspirants

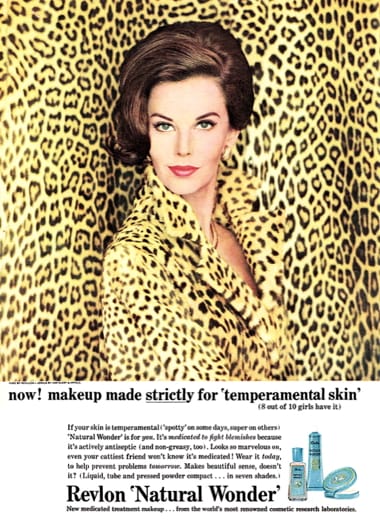

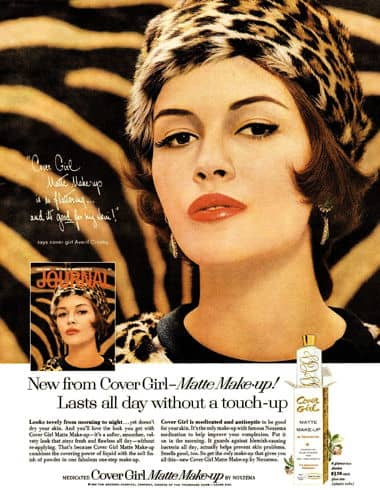

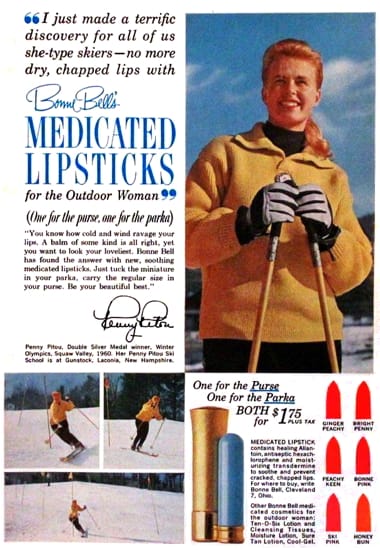

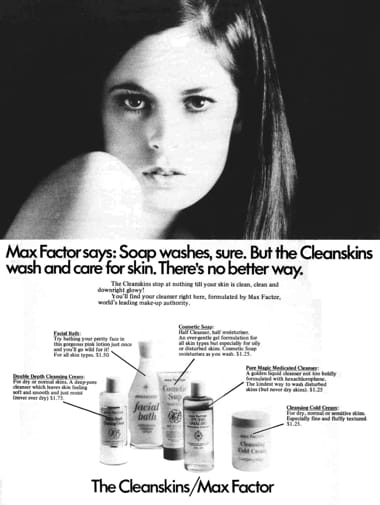

The main use of hexachlorophene in cosmetics was in the adolescent and problem skin market. It was widely employed in cleansers, masks and other skin-care products to combat the bacteria associated with pimples and acne. Some of the skin-care products introduced during the 1950s and 1960s that used hexachlorophene were: Max Factor’s Skin Clear Medicated Cleanser, Dorothy Gray’s Liquid Cleansing Cream, Tussy’s Medicated Lotion, and Helena Rubinstein’s Beauty Dew Cleansing Cream. Make-up with hexachlorophene included: Nozxema’s Cover Girl Liquid Make-up, Revlon’s Natural Wonder Medicated Cake Make-up, Yardley’s Shine-Stopper Medi-Blush, Max Factor’s Pure Magic Medicated Liquid Make-up, and Bonne Bell’s Medicated Lipsticks.

Above: Revlon Natural Wonder Medicated Cake Make-up. It included 0.05% pyridoxine (a form of vitamin B6) and 0.69% hexachlorophene.

Problems

Hexachlorophene was employed in a wide range of products but very little research was undertaken into its effects on the body. It was known that levels of hexachlorophene built up on the skin with regular use but health authorities did not think this posed a problem. The compound was not very soluble so it was thought to be very unlikely that hexachlorophene would be absorbed into the body.

By the 1970s, this attitude had begun to change. Some studies indicated that hexachlorophene was absorbed into the body and, once there, could affect the nervous system. However, before health authorities could respond to these reports a manufacturing blunder in France caused them to act. A number of infants had died after being dusted with talcum powder made incorrectly with a high level (6%) of hexachlorophene. In 1972, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) responded to the deaths in France by issuing a recall of consumer products containing more than 0.75% hexachlorophene. Other health authorities around the world also clamped down on its use.

By the time the FDA issued the recall notice, about 1.8 million kilograms (four million pounds) of the compound were being manufactured annually for use in medical and cosmetic products. The FDA directive therefore affected a large number of consumer goods.

I remember reading a commissioner’s meeting minutes where they opined that there were probably something like six to 12 products that had hexachlorophene in them. It turned out that there were something like 1,500 products with hexachlorophene.

… About 600 of those were recalled. They were mostly products that used hexachlorophene as a preservative; if the percentage was not minimal, up to three-quarters of a percent, they were moved behind the counter as prescription products; and if it was more than three-quarters of a percent, it was recalled.(Swann & Tucker, 2003)

Understandably, Givaudan-Delawanna, amongst others, thought the FDA response to the French tragedy was an over-reaction. However, commercial protests did not stop the ban and a wholesale replacement of hexachlorophene in consumer products took place.

Above: Dial Deodorant Soap now containing trichlocarban rather than hexachlorophene (Smithsonian).

Other outcomes

The removal of hexachlorophene from cosmetics after 1972 coincided with an increase in the marketing of ‘natural’ skin-care products and a shift to more ‘natural looking’ fashions in make-up, at least in the United States. This was already taking place by 1972 but the hexachlorophene scare, which increased consumer distrust of synthetic chemicals, may have accelerated the process. This distrust is still manifest today in the Clean Beauty trend.

The hexachlorophene recall also made cosmetic companies aware of the danger of closely associating a cosmetic with a synthetic compound. Products that were advertised as contining hexachlorophene suffered drops in sales when hexachlorophene’s neurotoxicity became public. Cosmetic companies continued to use synthetic ingredients but now became more wary about advertising their presence and avoided it where possible.

First Posted: 5th October 2015

Last Update: 26th February 2023

Sources

Fuller, J. G. (1972). 200,000,000 guinea pigs. New dangers in everyday foods, drugs and cosmetics. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Pines, W. L. (1972). The hexachlorophene story. FDA Papers, February, 11-14.

Price, P. B. (1951). Fallacy of a current surgical fad—the three-minute preoperative scrub with hexachlorophene soap. (1951). Annals of Surgery, 134(3), 476–482.

Seitz, E. P., & Richardson, D. I. (1988). Deodorant ingredients. In K. Laden & C. B. Felger (Eds.), Antiperspirants and deodorants, (pp. 345-390). New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.

Spitz, L. (2004). The history of soaps and detergents. In L. Spitz (Ed.), Sodeopec: Soaps, detergents, oleochemicals, and personal care products (pp. 1-72). Champaign, IL: AOCS Press.

Soap washes hands as clean as a surgeon’s. (1945). Popular Science. September, pp. 82-83.

Swann, J., & Tucker, R. A. (2003). History of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Interview with James C. Morrison. Retrieved September 24, 2015, from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/.../UCM265840.pdf

Tebbe-Grossman, J., & Gardner, M. N. (2011). Germ free: Hygiene history and consuming antimicrobial and antiseptic products. In N. Dayan & P. W. Wertz (Eds.), Innate immune system of skin and oral mucosa: Properties and impact in pharmaceutics, cosmetics, and personal care products (pp. 3-42). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

1949 Dial deodorant soap with hexachlorophene.

1954 G-11 brand of hexachlorophene. The Sindar Corporation, New York, was a division of Givaudan-Delawanna. It was not the only manufacturer. North Eastern Pharmaceutical & Chemical Co. (Nepacco) became a second U.S. supplier. The sales rights for Nepacco hexachlorophene were acquired by Nitine, Inc., a Shulton subsidiary, in 1969.

1954 Eskamel containing resorcinol, sulphur and hexachlorophene (UK).

1956 Mum cream deodorant.

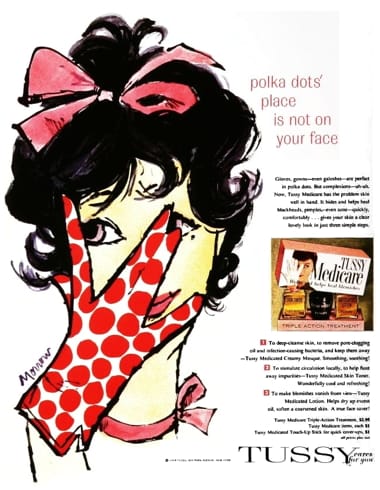

1960 Lehn & Fink Tussy Medicare. The triple action treatment included Tussy Medicated Skin Toner, Tussy, Medicated Cream Masque, and Tussy Medicated Lotion. There was also made a Medicated Touch-Up Stick for quick cover-ups.

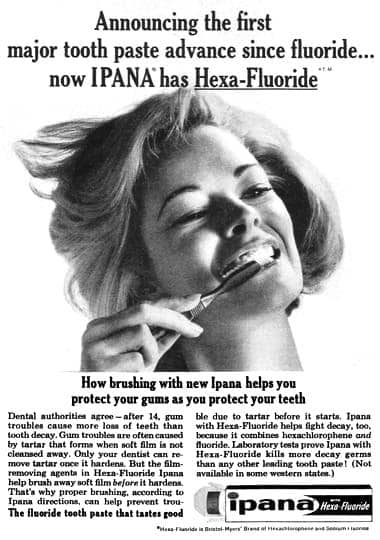

1962 Ipana toothpaste with Hexa-Fluoride, a combination of hexachlorophene and fluoride.

1963 Revlon Natural Wonder. A medicated make-up treatment in liquid, tube and pressed powder compact.

1963 Noxzema Cover Girl Matte Make-up. A medicated range consisting of a liquid, pressed powder, loose powder and matte make-up. Additional cosmetics medicated with hexachlorophene continued to be added to the Cover Girl range until 1972.

1964 Bonne Bell Medicated Lipstick.

1968 Stirling Drug pHisoHex. Once widely used in the treatment of acne, after 1972 the FDA restricted its use to health-care workers. In 1972, Stirling Drug introduced a non-hexachlorophene version called pHisoDerm.

1969 Max Factor Pure Magic Medicated Cleanser. This was part of the medicated Pure Magic skin-care and make-up range that contained hexachlorophene.

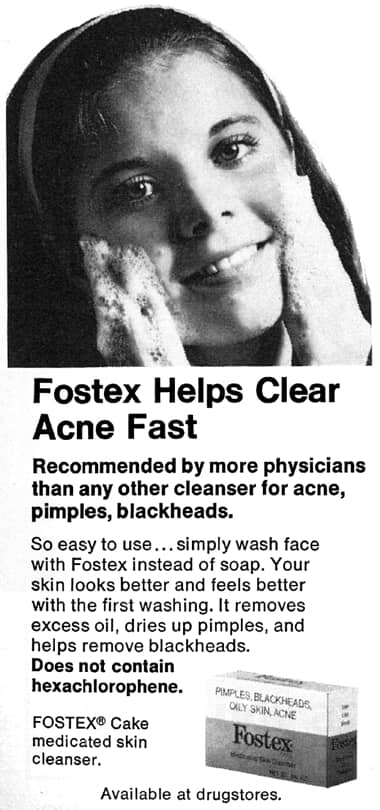

1973 Fostex Medicated Skin Cleanser making clear that it does not contain hexachlorophene.