Clay Masks

Clay masks, also known as complexion clays, clay packs and mud masks, were very fashionable in the 1920s after they became the first commercially manufactured cosmetic face mask to gain widespread use.

See also: Complexion Clays and the A.M.A.

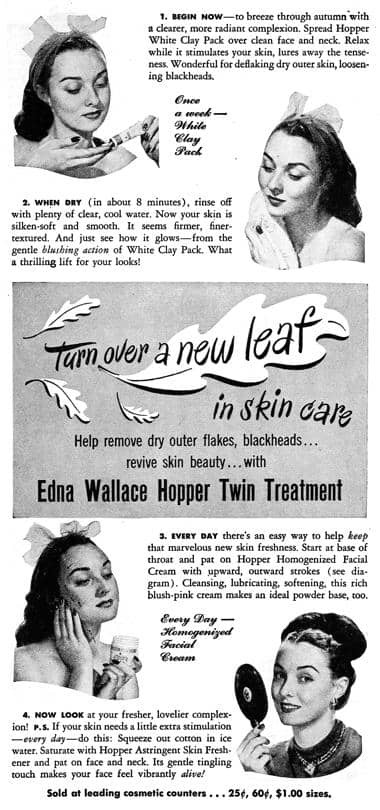

Some cosmetic companies, such as Edna Wallace Hopper, heavily promoted them long after this, but strong consumer interest had declined by the late 1920s and clay and/or mud masks have fluctuated in and out of favour ever since.

See also: Edna Wallace Hopper

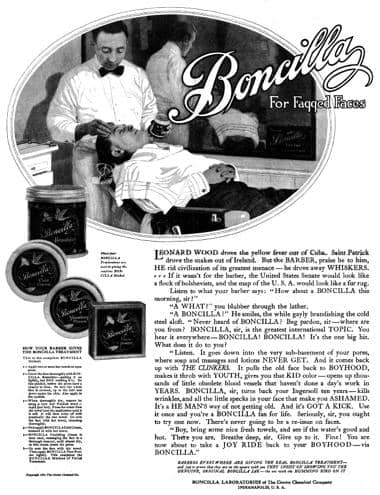

Commercial clay masks were retailed for home use but they were also sold to beauty salons and barber shops for use in facial treatments. However, many salon owners and barbers sidestepped commercial clay products and mixed up their own masks using readily available raw materials.

Qualities

Cosmetic chemists recommended that good quality commercial clay masks should:

1. Be a soft, smooth paste free from grit which can be easily smoothed over the skin with the fingers or a brush;

2. Adhere to the skin but be easily removed; and

3. Be attractive in feel, look and smell.

Clay masks were made with a range of earthy materials including bentonite, kieselguhr, hectorite, kaolin, Fuller’s earth, and montmorillonite. Muds were used in therapeutic mud packs applied to the body but products used on the face were usually made with materials of a finer grade – with no grit – so clays were generally preferred. Even so, it was recommended that delicate skin, such as the area around the eye, be avoided.

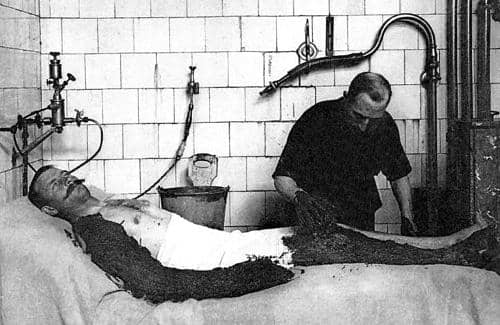

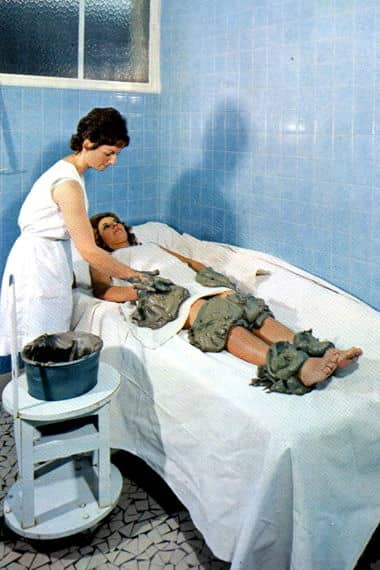

Above: c.1910 Mud packs being applied to arms and legs during a therapeutic treatment in a European spa.

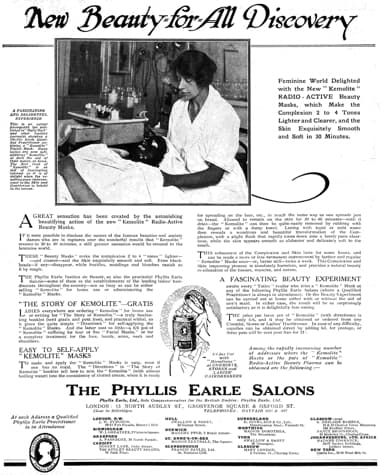

However, this does not exclude the use of muds and some were used very successfully in beauty facial treatments if extra care was taken when removing them. Radioactive earths were also widely used in the past. Some used naturally radioactive earths but radium was also added to complexion clays before the treatment began.

See also: Radioactive Cosmetics

Action

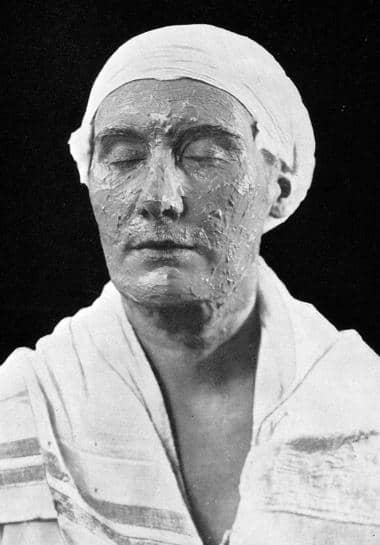

After the skin was cleansed, the clay mask was applied and left on the face for 20 minutes or so to dry. In the salon, the drying process could be speeded up by fanning the face or using a heat lamp.

The face is first thoroughly cleansed with a suitable cream. There is one that is generally used in connection with the mud mask, but the type of skin or its condition at the moment may call for a different cream, and this only the beauty specialist, who is an expert dermatologist, can decide. If the skin is particularly sensitive or inclined to be dry a more emollient and feeding cream is used. Then the mud mask is applied evenly all over the face and under the chin and allowed to dry and harden.

The patient is left in a recumbent position and generally in the dark with pads of cotton wool steeped in a soothing and astringent lotion over the eyes so that the treatment may be as restful as possible.

A special softening lotion is added to hot water for the process of removing the mask when the psychological moment arrives. With this solution it is gently and thoroughly softened before being wiped off.

The outfit for the home treatment includes a liquid to add to the paste to bring it to the right consistency should it get too dry, the cream for preliminary cleansing, and the softening lotion for removal.

After this treatment the face certainly feels and looks fresh and firm, and it is very useful for somewhat lined skins and women who are no longer young.(Chrysis, 1927)

As the water in a clay evaporates, the mask contracts and tightens. This led some to say that clay masks are ‘astringent’ but their action differed from the chemical astringents like tannic acid and alum.

See also: Skin Tonics, Astringents and Toners

Clay absorbs and adsorbs many impurities. The clay particles are also mildly abrasive so dead skin cells and other loose material come off with the clay when the mask is removed. These combined effects are the basis for the claims that clay masks ‘unclog pores’ and draw out ‘skin impurities and poisons’ and are the reasons they are best suited to oily skin.

Very soon the layer of mud begins to tighten, and gradually draws the open pores together, forcing out the waste matter. This produces a tingling, and even stinging sensation, as the stimulating ingredients force the blood vessels into activity and therefore health.

(Verni, 1946, p. 30)

The effects mentioned above are physical rather than chemical in nature. However, a wide variety of chemicals were added to clay masks to enhance their physical action. These included: humectants such as glycerin, sorbitol or propylene glycol to reduce the possibility of the mask solidifying in the container and to stop excessive hardening as it dried on the face; alcohol to speed up the drying time; adhesives such as glycerin or starch to hold the mask together on the face; plasticisers like sulphonated castor oil to reduce cracking; surfactants such as triethanolamine, lauryl sulphate or lanolin alcohols to facilitate the rewetting of the mask so that it was easier to remove; perfumes to make it smell nice; and colours to improve the look. If insoluble pigments rather than dyes were used to colour the mixture this eliminated the possibility that the skin would be stained during the 20 minutes or so the mask was on the face.

All Purpose Mask Bentonite, best 14 parts Sulfonated castor oil 5 parts Glycerine 2 parts Water to make 100 parts Color and perfume q.s. Dissolve the castor oil and glycerine in water. Place water on a rapid mixer. Slowly add the bentonite during agitation. Mix 15 minutes. Set aside overnight. Colour and perfume. Mill into smoothness.

(deNavarre, 1938, p. 278)

Purified kaolin 32.0% Kieselguhr 10.0% Glycerin 15.0% Alcohol 20.0% 2% acacia mucilage 10.0% Water 12.0% Perfume 1.0% Heat the water and glycerin to 170°F. Run it into a mass mixer; add the dry materials and mix for about two hours. Then add the mucilage and the perfume dissolved in alcohol. Greater fluidity can be obtained by increasing the water content.

(Thomssen, 1947, p. 494)

The tightening effect of a clay masks could be enhanced by adding chemical astringents such as benzoin, tannin, aluminium salts, borax or magnesium sulphate.

Astringent Mask Zinc phenolsulphonate 5 parts Boric acid 1 part Clay q.s. Water to make 100 parts In place of the zinc phenolsulphonate, magnesium sulphate or alum can be used in like amounts. Boric acid may be replaced by citric acid just as easily. The clay can be either talc, kaolin, Fuller’s earth, or bentonite. If any of the first three, the product may require as much as 50 per cent. or more pigments to give a solid product. If bentonite is used, it requires not over 15 per cent.

(deNavarre, 1938, p. 278)

Clay masks could also act as a facial bleach with the addition of a little hydrogen or zinc peroxide or could cool and tone the face if a little camphor or menthol was included.

BLEACHING CLAY Tri Calcium Phosphate 87 lbs. Zinc Peroxide 12 lbs. Mineral Oil 5 lbs Glycerin 15 lbs. Water 25 lbs. Zinc Stearate 6 lbs. Perfum 3 ozs Procedure: Mix Tri calcium phosphate, zinc peroxide, zinc stearate, water and glycerine. Mix until smooth, add oil and perfume.

(Beauty Clays, 1933, p.159)

Manufacturing

Manufacturing clay masks was a relatively simple process but powerful mixers were needed to blend the heavy materials. The finished paste was prone to drying out so the masks had to be packed in well-sealed tubes or jars. Some producers avoided this problem by selling their masks as a powder, leaving it up to the user to mix this into a paste by adding water or an accompanying liquid.

First Posted: 3rd September 2017

Last update: 25th March 2025

Sources

Alexander, P. (1968). Face packs – beauty masks. American Perfumer and Cosmetics, 83, August, 49-54.

Chrysis. (1927). Masks. Eve: The Lady’s Pictorial. London: Sphere and Tatler.

Beauty Clays. (1933). The Drug and cosmetic Industry. February, 32(2), 159-160.

deNavarre, M. G. (1938). The newer face masks. Manufacturing Perfumer, September, 277-279.

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston, MA: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc.

Robertson, R. H. S. (1986). Fuller’s earth: A history of calcium montmorillonite. Hythe, Kent: Volturna Press.

Searle, A. B. (1933). Complexion-clays and mud-packs. The Manufacturing Chemist. September, 261-264.

Thomssen, B. S. (1947). Modern cosmetics (3rd ed.). New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

Verni, M. (1946). Modern beauty culture (2nd ed.). London: New Era Publishing.

1921 Boncilla Clasmic Pack. The advertisement shows a barber applying this to a client during a facial, something that was more common in barber shops in the past.

1922 Phyllis Earle Kemolite Facial (London). Kemolite contained radioactive earths.

1936 Boncilla Beauty Mask.

Applying a mud pack in the salon with a spatula (Verni, 1946).

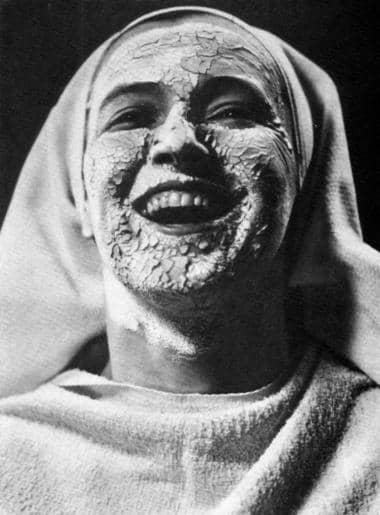

Face of a client just covered with Fuller’s earth with the clay still wet and shiny (Verni, 1946).

Clay mask cracking, something that was more common in early formulations or non-commercial products made almost solely from clay and water.

1945 Edna Wallace Hopper Twin Treatment. White Clay Pack followed by Homogenized Facial Cream.

Therapeutic mud pack from the 1970s. Mud packs are also used in body treatments in Beauty Culture.

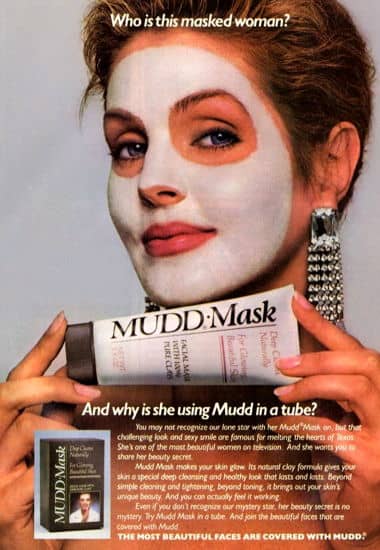

1987 Mudd Mask.