Corrective Make-up (Contouring)

Make-up can improve the appearance of the face by covering skin blemishes but it can also add to its beauty by changing the apparent size and shape of facial features. This is done with optical tricks – long used in drawing and painting – that employ highlights and shading to reshape the apparent appearance of facial contours. Used effectively, make-up can ‘adjust’ facial features such as a wide nose, thin lips, or a large jaw to create an ‘illusion of loveliness’. These make-up optical tricks have been described as ‘corrective’ but the practice is also known as ‘contouring’.

Origins

Using make-up to cover facial defects goes back to its ancient origins but, in the modern world, it got a boost from the efforts of Lydia O’Leary [1900-1982], the developer of Covermark. In the late 1920s, she introduced two new classes of cosmetics into twentieth-century beauty, camouflage make-up and concealers. Camouflage make-up is a specialist area but concealers became a staple part of general (street) make-up through to the present day.

See also: Concealers and Covermark

The use of optical tricks in general make-up also has a relatively long pedigree. However, in the past, the meagre shade ranges of foundation and powder limited their use in facial contouring. Lipstick and eye make-up could alter the perceived shape and size of the lips and eyes respectively but most of the optical effects used to change the apparent size and shape of other facial features were accomplished with rouge when it was used as a shadow. These examples from Helena Rubinstein are typical:

HINTS FOR APPLYING ROUGE

If your face is oval, apply your rouge in a “triangle”, from temple towards nose and thence to ear.

A round face can be made to seem longer if rouge is placed high up on the cheek bones, just between the eyes and close to the nose.

The long face will look rounder or more charmingly oval with rouge applied low on the cheeks and covering a large surface.

If the eyes are large and bright, rouge brilliantly. A very faint touch of color may be applied directly below the eyebrows.

If the eyes are small, soft and serene, less rouge is needed.

If the nose is a trifle too long, a hint of rouge beneath the tip will make it appear shorter.

The longer upper lip can be shortened in effect by ever so faintly rouging the little ridge extending from the nose to the mouth.

Delicately rouging the chin, shortens the very long face and the merest touch of pink to the lobes of the ears will narrow the apparent width of the face too broad to be called beautiful—that is, according to the standard of the Occident.(Helena Rubinstein, c.1928, pp. 4-5)

In the 1930s, optical tricks created with rouge were supplemented by more sophisticated practices developed by the motion picture industry in a time of crisis.

Film make-up

The stock market crash of 1929, reduced box-office takings and many Hollywood studios slipped into deficit having borrowed heavily to pay for the sound equipment needed for ‘talkies’. Some studios, such as Paramount-Publix, Fox Film, RKO Pictures and Universal Pictures, went into receivership while others, like Warner Brothers, only managed to avoid financial disaster by ruthless cost-cutting.

In these difficult economic times, Hollywood turned to movie stars to attract people back into theatres. Stars had been used as box-office draws in the 1920s but their pulling power now became critically important and the studios went to great lengths to make them look as attractive as possible on the screen. Some of this could be done with sympathetic lighting but make-up increasingly supplemented the efforts of cinematographers. Fortunately, by 1930, Hollywood make-up artists had the tools to put more sophisticated make-up techniques into practice.

Early motion pictures were screened in black and white, filmed using blue-sensitive or orthochromatic film. These early film stocks suffered from two main drawbacks. First, they were insensitive to the red end of the spectrum so red would photograph as black. This made players’ faces look darker on the screen and if there was any unevenness in their complexion their face look dirty. Second, the restricted sensitivity of blue-sensitive and orthochromatic film to the visible spectrum meant that they had a limited ability to render different shades of grey. This could create sharp contrasts on film where the eye saw a gradation.

Under these conditions, the primary function of early film make-up was to cover facial blemishes and give players the appearance of a smooth, light complexion.

See also: Early (Silent) Movie Make-up

After 1927, blue sensitive and orthochromatic film was replaced with panchromatic. This film stock captured the full visible spectrum and rendered black and white tones closer to their appearance in everyday life.

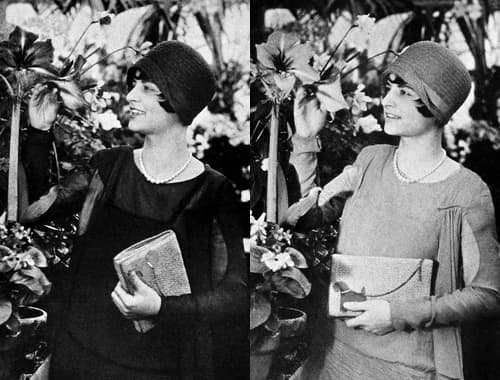

Above: Orthochromatic film (left) and panchromatic film (right). The woman’s dress is red, the large flower deep red, the dog on the handbag blue, and the potted plants are pink. Panchromatic film renders their colour values better than orthochromatic film.

See also: Panchromatic Make-up

The adoption of panchromatic film and the subsequent development of panchromatic make-up by Max Factor, Leichner and others, allowed make-up artists to develop more sophisticated make-up techniques which included contouring. One of the primary instigators of this trend was Perc Westmore [1904-1970], the chief make-up artist at Warner Brothers. The make-up system Perc developed at Warner Brothers in the early 1930s involved contouring but he called it ‘Corrective Make-up’ which, as far as I can tell, is the first recorded use of the term.

Most beauty is illusion. The sole purpose of using make-up is to enhance your loveliness, or to create an illusion of loveliness. … Small eyes can be made to look large . . . square jaws can be softened.

The face itself cannot be changed, but its appearance . . . its illusion can. You can detract from your bad features and emphasize your good features through proper application of make-up.(Westmore, 1939, p. 4)

The contouring techniques used in Westmore’s ‘Corrective Make-up’ were soon adopted by make-up artists working in other Hollywood studios during the 1930s including Jack Dawn [1892-1961] at Universal.

When a cinematographer photographs a player, he literally paints a picture on his emulsion, using light and shade as his brush. He has two main objectives: first, to suggest an illusion of three-dimensional roundness on the actually flat, two-dimensional screen. Second, to enhance the good points of the player’s appearance, and conceal the unfavorable ones.

In both instances, his tools are light and shade. To conceal an undesired protruding area, such as, for instance, a chin that is beginning to sag, he tries to keep that area in shadow. To eradicate wrinkles, he throws additional soft, very flat light into them to light up the concavities.

In applying a “corrective” make-up, the make-up artist uses essentially the same means. Only instead of actual light and shadow, he uses lighter or darker applications of make-up to produce essentially the same result. In the case of the sagging chin, he throws it, photographically, in the shadow by applying a slightly darker shade of make-up to that area.(Dawn, 1941, p. 514)

Although these contouring techniques were described as ‘new’ they were based on similar practices long employed in stage make-up as the quote below clearly shows.

The proper understanding and arranging of light and shade of the high lights and the low lights is, perhaps, the most important factor in the success of a make-up [for the stage], and is only learned after much practice blended with a certain amount of natural skill. By the means and right use of light and shade the whole shape, size, and the character of the face may be entirely changed. Thin cheeks can be made round, hollow cheeks full, and fat ones thin and hollow.

(Adair Fitz-gerald, 1901, p. 32)

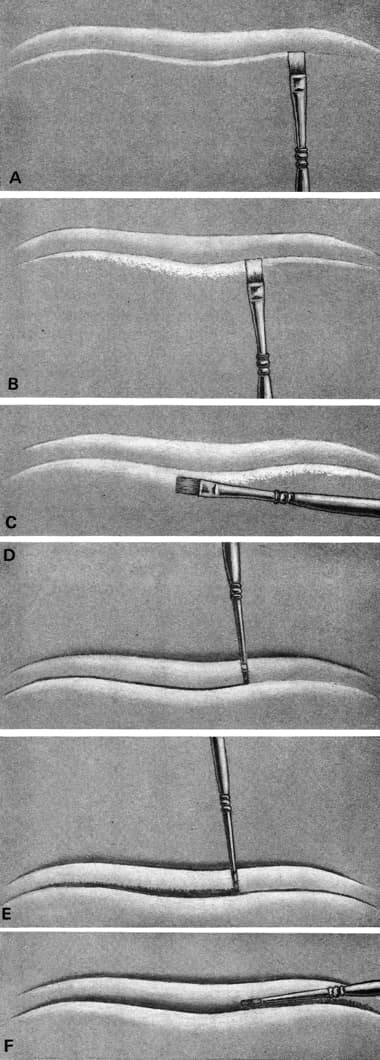

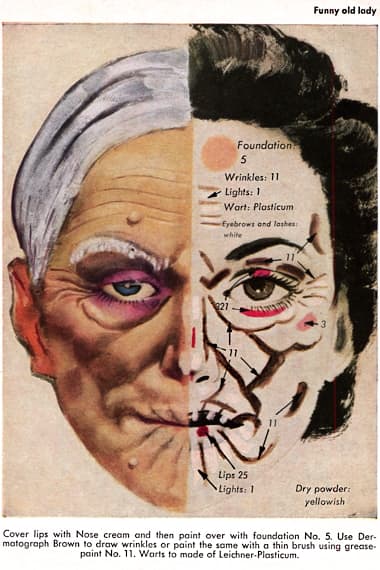

Contouring with light and dark make-up for the stage was particularly useful in character make-up and in changing the apparent age of a player. Stage make-up books covered the subject in detail and charts detailing the make-up plans for a range of aged and other stock characters that involved contouring were available from the early nineteenth century first from Leichner and later from Max Factor.

Also see the booklet: Leichner stage make-up (c.1979)

However, although similar, there were differences in the way contouring could be used on stage and screen. Stage make-up was viewed at a distance so contouring techniques needed to be bold to create an illusion. Screen make-up was highly magnified on the screen during close-ups so contouring for film had to be subtle if a natural-looking effect was to be realised. Fortunately, the wider gray-scale range provided by panchromatic film enabled make-up artists to do this.

General make-up

In 1935, the Westmore brothers – Perc Westmore, Monte Westmore [1902-1940], Wally Westmore [1906-1973} and Ern Westmore [1904-1968] – opened the House of Westmore and, soon after, developed their own cosmetic line. In promoting their general (street) make-up range, the Westmores stressed their links with Hollywood and the corrective make-up techniques they used to make movie stars look more attractive. This created a good deal in interest from other cosmetic houses and the ideas behind ‘Corrective Make-up’ promoted by the Westmores and later by Max Factor began to appear in the make-up handbooks released by other cosmetic companies. The ideas previously implemented with rouge were now extended to foundation and/or powder.

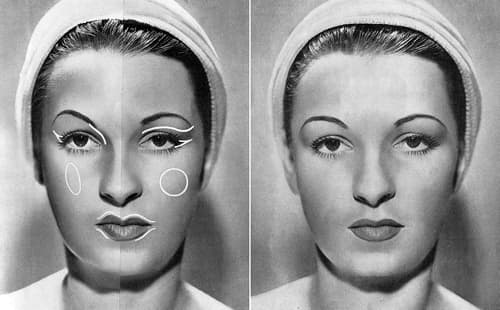

Above: 1941 Sculpting the face with make-up shadows (Aubry, 1941).

Face shapes and contouring

The Corrective Make-up System developed by Perc was based on an ideal photographic face that was oval in shape. Other face types therefore needed to be ‘corrected’ to give them the illusion of being more oval than they were in reality. When making up the face of an actress, her face type would first be identified – Oval, Round, Square, Oblong, Triangle, Inverted Triangle and Diamond – and then make-up and hairstyling was used to bring the appearance of her face closer to the ideal.

See also: The Ideal Face and Face Shapes

The Westmores developed the concept of the ideal photographic face in conjunction with Max Factor and both used it in their advertising. The idea of the perfect oval face had been around before the 1930s but the combined influence of Max Factor, the Westmore brothers and Hollywood gave it a new emphasis. Most cosmetic companies of the time also tied their advice on corrective make-up to face shapes, and a lot of current advice about contouring still relies on it today. However, as Kehoe (1969) points out, its use is founded on a misconception. The perfect oval face promoted in the 1930s and 1940s was based on a photographic effect particular to black-and-white photography.

[T]he oval face, because it presented the most pleasing planes and was the easiest to light and photography symmetrically from almost any frontal angle, was considered by the motion picture industry to be the most “photogenic” shape. Therefore, all other facial shapes presented photographic problems from their standpoint. So, the make-up artist devised a method of shading certain facial areas, such as the jawline, chin, cheeks or forehead, with a deeper colored foundation base that photographed a darker shade of gray than the rest of the face. The feature so shaded, because it went into shadow, appeared to be minimized or less prominent. The same principle was applied to the areas which required accent or highlighting by applying a lighter colored foundation which photographed a light shade of gray.

(Kehoe, 1969, p. 58)

As Kehoe goes on to note, what worked in black-and-white photography did not automatically transfer to general makeup. Street make-up is in colour, is viewed from a range of distances, and needs to function in a number of different, uncontrolled lighting conditions. Make-up techniques, including contouring, can still be used to emphasise a woman’s best features and minimise the less desirable ones but this is best done on an individual basis, not by bringing it closer to an oval ideal.

First Posted: 9th November 2020

Last Update: 30th October 2022

Sources

Adair Fitz-Gerald, S. J. (1901) How to make-up: A practical guide for amateurs and beginners. London: Samuel French.

Aubry, F. (1941). Comment sculpter le visage par les ombres du maquillage. Votre Beauté February, 14-15.

Corson, R. (1990). Stage makeup (8th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Dawn, J. (1941). Corrective make-up can help the cinematographer. American Cinematographer, November, 514, 540.

Gerson , J. (1979). Standard textbook for professional estheticians (Rev. ed.). Bronx, NY: Milady Publishing Corporation.

Helena Rubinstein. (c.1928). Personality make-up [Booklet]. U.S.A.: Author.

Kehoe, V. J-R. (1969). The technique of film and television make-up for color and black and white. London: Focal Press.

McLeod, E .T. (1949). Beauty after forty. Garden City, Ny: Nelson Doubleday Inc.

Pirchan, E. (1951). Das maskenmachen und schminken: Anleitung zur ausführung von maskierungen. Ravensburg: Verlang Otto Maier.

Rose Laird. (c.1938). This way to loveliness [Booklet]. England: Author.

Thudium, L. (1999). Stage makeup: The actor’s complete step-by-step guide to today’s techniques and materials. New York: Back Stage Books.

Westmore, P. (1938). Make-up specialists can do much to assist the cinematographer. American Cinematographer. 19(1), January, 13, 40.

Westmore, P. (1939). Perc Westmore’s make-up guide with measuring wheel to type your own face [Booklet]. Hollywood, CA: House of Westmore.

‘Garment Study For A Seated Figure’ by Leonardo da Vinci [1452-1519] that uses light and dark to create the illusion of three-dimensional volume.

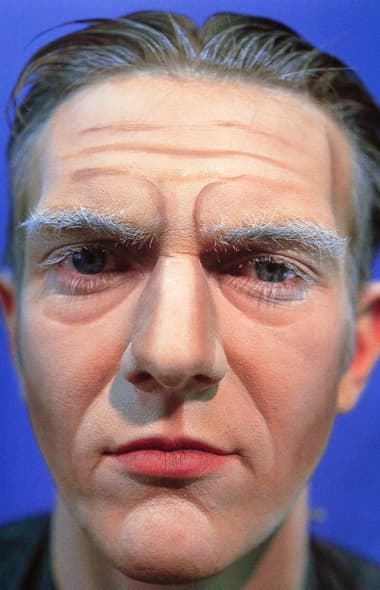

Highlighting and shadowing create the illusion of facial folds and eye bags associated with age in stage make-up (Thudium, 1999).

Creating wrinkles with shading and countershading in stage make-up (Corson, 1990).

Make-up chart illustrating how to apply light and dark greasepaint to create the facial contours associated with an aged face (Leichner, c.1979).

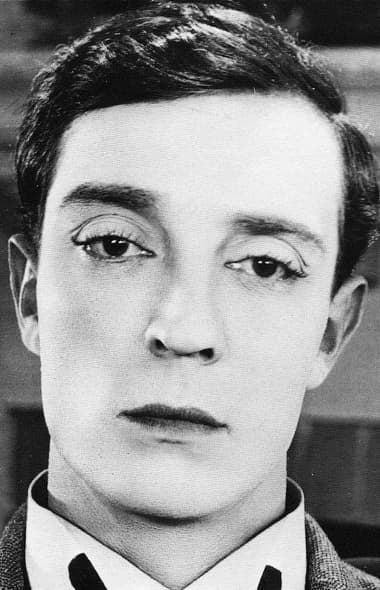

Buster Keaton [1895-1966] used make-up to flatten facial features to create his trademark deadpan face, free of blemishes and lines.

1927 Pauline Starke [1901-1977] had a flawless complexion that required very little make-up in close-ups. However, she is using corrective make-up to increase the perceived size of her lower lip.

1949 Applying rouge by face shape (McLeod, 1949).

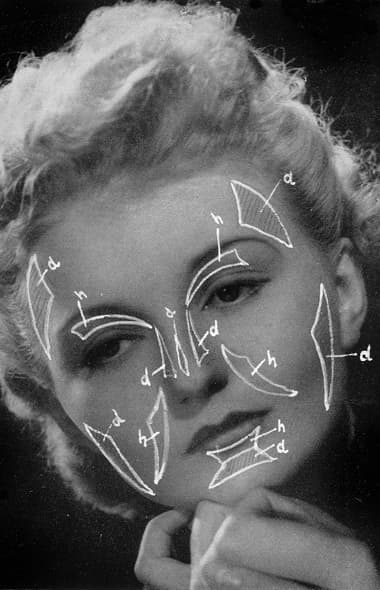

Diagram using light and shade to change the perceived contours of the face. d = dunkler (darker); h= heller (brighter) (Pirchan, 1951).

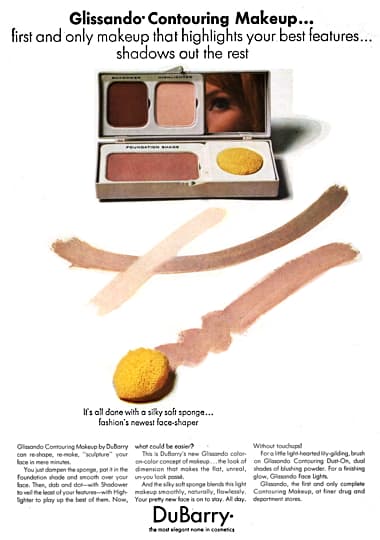

1966 Glissando Contouring Makeup.

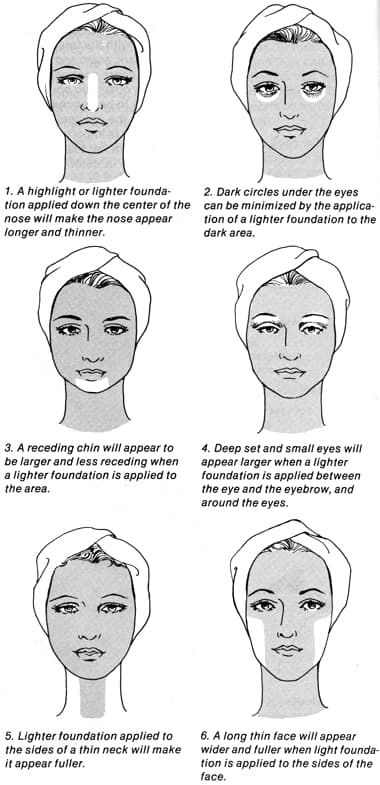

Highlighting used to change the appearance of facial features (Gerson 1979).

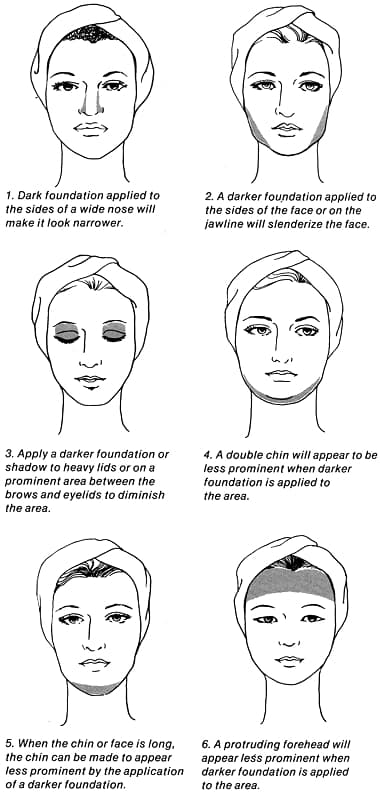

Shadowing used to change the appearance of facial features (Gerson 1979).