Loose Face Powders

The use of ‘paint’ was criticised in Victorian times but a pale, flawless skin was fashionable so many women resorted to a face powder to cover blemishes like sunburn, spots and freckles. Perspiration and oily secretions could also be rectified with powder, making it useful in places where summers were warm and women were more likely to ‘glow’.

The use of face powder rose steadily towards the end of the nineteenth century but was still viewed by many as ‘injurious’ to the skin, either because powder was believed to interfere with the natural functions of the skin by blocking the skin’s pores or contained harmful ingredients like lead.

[A]ll powders are injurious, whether they be chemically pure or not. They close up the pores of the face and destroy the natural functions of the skin. After a woman has used powder for any length of time, her face becomes hard and her skin scaly. Then cream or glycerine must be applied every night to soften the skin and open the pores.

(The Daily Reporter, Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, 1885)

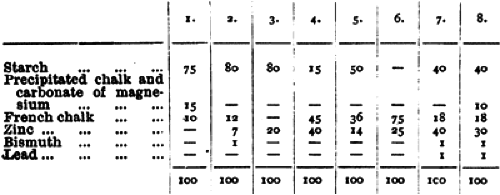

These ideas persisted into the twentieth century and were not without some basis. Tests conducted in 1897 by Dr. William Murrell indicated that some face powders made at the turn of the century did contain lead.

Above: Table showing the results of a chemical analysis of eight face powders (Murrell, 1897, p. 602).

To counteract these misgivings, and the occasional attack by the medical profession, early manufacturers and their cosmetic chemists made numerous pronouncements defending their use.

At all events the proper use of powder is beneficial, it lightly covers and unifies a complexion, hiding the ravages of time, improving even the beautiful face.

… [T]here is no legitimate reason against the use of face powder, and the pharmacopeias prescribe them in the treatment of many skin affections. They are of benefit in acné [sic], freckles, sunburn and red nose.

Beneath their attractive aspect and odor, face powders should be made by the perfumer to combine the qualities of an elegant cosmetic and therapeutic agent; they must primarily possess adherence, lightness and be transparent; secondly, they should be detergent and delicately absorbent in order to aid the natural functions of the skin, taking up the fatty matters not easily dislodged by water; they should also tend to increase the natural elasticity and regular functions of the skin.(Mazuyer, 1910, p. 266)

Criticisms of face powders, and cosmetics in general, declined during the twentieth century but did not cease altogether. Needless to say most were from men.

See also: Complexion Clays and the A.M.A.

Commercial powders

Many nineteenth century beauty books contained recipes that readers could use to make face powder at home. However, as the century drew to a close, more women chose to purchase face powders from local chemists/druggists – usually sold in unmarked packets – or bought trade-named powders generally sold in decorated powder-boxes.

These early commercial face powders were generally simple mixtures of three or more substances. Common ingredients included talc, natural starches like potato and rice, calcium carbonate (chalk), magnesium carbonate, kieselguhr (diatomite), washed china clay (kaolin), bismuth subchloride and subnitrate, zinc and magnesium stearate, ground orris root and zinc oxide. Some of these, such as orris root and bismuth compounds, fell out of favour, while others, like zinc oxide, that were initially treated with suspicion, became staple ingredients.

The substances from which … powder is chiefly made are the following: Starch-flour, such as wheat starch, rice starch, corn (Maize) starch, potato starch, also pistachio-nut flour; all these starches are well adapted for the powders under consideration, because, owing to their fineness, they always lie close together and consequently display good covering power. Further, good use is made of carbonate of magnesia, bismuth white and especially talcum, in addition, occasionally, the finest sifted chalk. A very important constituent of powder is oxide of zinc, owing to its great covering power, also by reason of its adhesive properties, as an addition to the lighter kinds of starch and also of carbonate of magnesia. It forms an important component of all kinds of powders, aside from the fact that from a hygienic point of view it is very desirable. In addition to oxide of zinc, stearate of zinc merits special mention because, by reason of the large amount of stearine it contains, it possesses unusual adhesive properties, which cannot be too highly considered.

(Mann, 1912, p. 161)

In the first half of the twentieth century, loose face powders developed from these simple beginnings into a widely-used cosmetic with an extensive array of commercial products.

Formulation

Although they appeared relatively easy to make, even as late as the 1960s, cosmetic chemists still found it tricky to create a formula for loose face powder that functioned well under all conditions.

Certain face powders are readily made, but it is not easy to produce a really good face powder, i.e., one that spreads well and smoothly on the skin, has the right matt look and degree of opacity, wears well in hot weather and blustery weather, is available in a variety of color shades, is attractively perfumed; and is at all times uniform and consistent in quality.

(Wells & Lubowe, 1964, p. 215)

The formula selected was also affected by how the powder was to be marketed.

Will the powder be used as a finishing touch at the end of a beauty treatment? Will it be the central part of a simpler line around which other products will be built? Will it be subject to high fashion, with types and shades changing from year to year? Will it be a standardized product to reach a more conservative clientele? Is it designed for teenagers or for more mature women? Must it merely remove shine from the face, or should it be highly colored and cover blemishes as well?

(Martin, 1957, p. 263)

Powder base

Once the marketing questions had been answered, a cosmetic chemist had to formulate a powder that met the qualities needed. Leaving aside decisions about what perfume to use or what shades to make, the remaining qualities of a face powder were determined by the white or off-white ingredients of the powder base which largely determined the powder’s texture, covering power, staying power, absorption properties and ease of application.

Covering power

The main function of early face powders was to visually cover the skin, so that shine was reduced and imperfections were hidden. The amount of concealment needed varied from woman to woman, so powders were produced in various grades loosely referred to as light, medium and heavy.

The types of skin which face powders must cover are dry, normal, moderately oily, very oily. Because dry skin secretes very little moisture and no oil, it requires a powder of light covering power. Normal and moderately oily skins, being more shiny due to secretion of oil and moisture, require a powder with more covering power. Very oily skins having a high shine require a powder of special covering power.

(Thomssen, 1947, p. 48)

Although the idea of linking covering power with oil absorbency was followed for many years, it was overly simplistic. First, the amount of cover had more to do with fashion than with skin type – compare the use of more opaque powders of the 1930s with the transparent powders of the 1970s – and second, younger skins with a higher oil content generally show fewer blemishes than older skins with a lower oil content. Taking just these two factors into account, it seems better to separate the ability of a face powder to hide imperfections (covering power) from its capacity to reduce shine (absorbency) and this was the direction most cosmetic chemists eventually took.

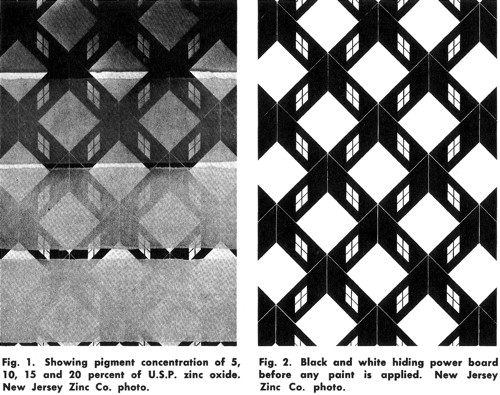

Above: Testing the covering power of various concentrations of zinc oxide (deNavarre, 1941).

Zinc oxide, kaolin, magnesium oxide and starch were all used to improve the covering power of early face powders but their effects were not as strong as titanium dioxide, a brilliant, white, inert powder. It began to be widely used in face powders in the early 1930s and it proved to be three to four times better than zinc oxide as a covering agent (deNavarre, 1941). When titanium dioxide was used in varying amounts with zinc oxide, any grade of powder could be produced.

White base for light powders with zinc oxide

% Zinc oxide 22.83 Talc 67.63 Zinc stearate 6.25 Prepared chalk or magnesium carbonate 2.25 Perfume 1.04 White base for medium powders with zinc oxide

% Zinc oxide 26.04 Talc 65.46 Zinc stearate 5.21 Prepared chalk or magnesium carbonate 2.25 Perfume 1.04 White base for heavy powders with zinc oxide and titanium dioxide

% Titanium dioxide 3.00 Zinc oxide 21.25 Talc 68.29 Zinc stearate 4.17 Prepared chalk or magnesium carbonate 2.25 Perfume 1.04 (Thomssen, 1947, pp. 59-60)

The covering power of a powder is also affected by the size of the powder particles. In general, powders get progressively more opaque as their particles get smaller. However, some powders, like titanium dioxide, can become transparent when their particles get below a certain size.

Particle size also affects the covering power of the powder in another way. Face powders made with smaller particles tend to be denser. This means that a greater amount of powder per unit area will be delivered to the face by the puff so the powder will be more opaque, all other things being equal.

The covering power of loose face powders was initially one of their most important features but this became less so as twentieth century progressed. As women began to use specialist concealers, or cosmetics that acted as foundations, the need for very opaque powders diminished. Other cosmetics were used to form a uniform undercoat over which a relatively transparent powder was applied. Not all manufacturers followed this trend. Some actually increased the opacity of their loose face powders to match the effect of the newer cake make-ups and pressed cream powders that became common after the Second World War.

Absorption

This quality refers to the ability of a powder to absorb perspiration and oils. This ability also enabled powder absorb perfumes used to scent them. Ingredients used to carry out this function initially included substances such as kaolin, magnesium carbonate, starch and chalk (calcium carbonate) but others were added later. For example, fumed (pyrogenic) and colloidal silica appears to have been introduced into face powders in the 1930s. It became popular with chemists formulating ‘blotting’ powders aimed at teenagers (deNavarre, 1975).

Blotting powder

(parts by weight) Talc 68 Magnesium carbonate 2 Fumed silica 15 Kaolin 10 Titanium dioxide 10 Color and perfume q.s. (deNavarre, 1975, p. 941)

Adhesiveness

The staying power of a face powder, its ability to stick to the skin, is referred to by cosmetic chemists as its adhesiveness. Lack of adhesion was a common problem with early face powders and many women resorted to using a vanishing or cold cream before powdering to help their face powder stay in place.

See also: Vanishing creams and Cold Creams

Magnesium, zinc or aluminium stearates were commonly included to help powder stick. Zinc stearate was a popular choice but magnesium stearate was preferred by some chemists as it was ‘fluffier’. The use of these compounds had their limits; if too much was used they could clog machinery sieves making the powder difficult to sift (Silman, 1936).

Proprietary powder bases introduced in the 1930s were used by many instead of stearates. These bases included substances made from zinc and magnesium salts of fatty acids or zinc and magnesium salts of palmitic, stearic and myristic acids, all of which improved the ability of the powder to cling to the skin. As well as showing strong adhesive properties these proprietary powder bases also exhibited a much greater slip or spreading quality than some of the stearates they replaced.

Slip

Slip is the property that enables a powder to be easily and smoothly applied without any feeling of drag. As a property slip is hard to define in any quantifiable fashion but like powder grittiness it can be felt with the fingers or on the face. While a number of ingredients can contribute to giving a powder slip – such as the kaolin, the stearates and starch – by far the most important substance is talc (magnesium silicate) which is why it made up to 50% or more of some face powders. It combines high spreadability (slip) with low translucency and covering power and feels smooth on the skin.

Once a manufacturer has a suitable powder base, the two other components of a loose face powder – perfume and colour are mixed into it. This is not to say that each of the powder components can be treated separately; they can affect each other, requiring adjustments in the final formulation.

Perfume

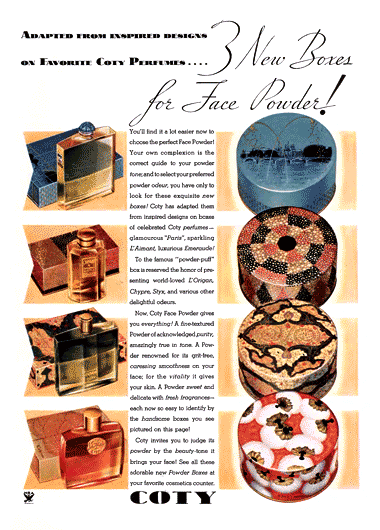

An attractive scent was essential if a powder was to enjoy good sales and many firms, from Colgate to Coty, sold powders with varying scents that matched to their range of fragtances.

Care had to be taken when selecting a perfume as the powder base could modify the perfume’s odour, making it smell musty. In addition the scent could also discolour the powder and darken the shade. Smaller firms could avoid such problems by purchasing their perfumes from specialist supply houses who dealt with such matters, while larger companies would compound their own scents, tailoring them for use across an entire range of cosmetics.

The addition of a perfume to a powder generally required the powder to be matured or aged for up to a month before it was packaged and sold. Depending on the manufacturing process, ageing could be done before or after the powder was made. If the perfume was mixed into a portion of the powder, e.g. the kaolin, it would be stored and matured before being incorporated into the rest of the powder mix; if it was sprayed on to the powder during the mixing process then the entire powder mixture would be aged before it was packaged.

Colours

As well as the powder base and perfume, face powders were also coloured to match skin tones. At first the range of colours was limited, with Natural (or Naturelle), Rachel, Rose, Brunette, and Flesh being common shades or tints. Natural (clear pink shades) were originally considered more suitable for blondes with Rachel shades more suited to brunettes.

For Flesh Tint— 1. Yellow ochre 90 parts Bole 6 parts Carmine 4 parts 2. Yellow ochre 90 parts Bole 3 parts Hydrated ferric oxide 2 parts Carmine 5 parts For Pink Tint— Yellow ochre 75 parts Carmine 25 parts For Cream or Rachel— Yellow ochre 94 parts Bole 4 parts Burnt sienna 2 parts Of the forgoing concentrated tinting powders from 60 to 120 grs. are required for each pound of white face powders.

(Lucas, 1914, p. 281)

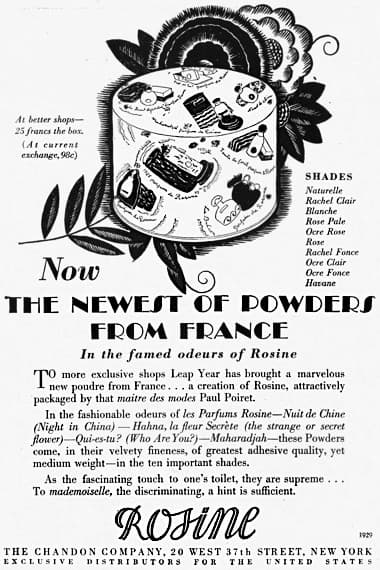

During the 1920s, as make-up became more socially acceptable, colour became more important and increasingly subject to the vagaries of fashion. For example, many companies introduced darker shades in their lines to match the browner complexions produced by the new fashion of suntanning. Cheaper powders in the 1920s rarely exceeded six shades – with the most common shades being White, Natural, Flesh and Rachel/Brunette but some companies had a dozen or so shades in their powder range at any one time.

The colours used in face powders came mainly from two sources: inorganic pigments like iron oxides (ochres, siennas, and umbers) and organic lakes and toners; both types being increasingly controlled by legislation. Inorganic pigments were originally sourced from nature but synthetic forms were later preferred. Synthetics were less likely to have contaminants, were free from grit, more uniform in colour from batch to batch, and, being purer, had a greater strength of colour than their natural counterparts.

Inorganic pigments were very stable and had an indefinite shelf life but lacked a certain brilliance so, despite being less stable when exposed to light, organic lakes were often included into face powders as well. Any lake colour selected needed to be tested for stability and checked to ensure that it did not readily dissolve in water or oil, otherwise the colour would bleed in areas where perspiration or sebum was present.

Even if no bleeding occurred, sebum could still have an adverse effect on a powder. Many face powders turned darker and yellower, or darker and redder after they had been on the skin for a while, a problem exacerbated by the fact that colour changes were greater where more sebum was produced making an evenly applied face powder look blotchy after a while (Kalish, 1944).

Since the ingredients in the base were white or off-white they would also affect the powder shade. Consequently, if a manufacturer was making up powders in light, medium and heavy grades, the colours used in each would need to be adjusted to compensate for the varying levels of titanium dioxide and/or zinc oxide used in the different grades to ensure that all were the same shade.

As well as the inorganic pigments and lakes other colouring agents have been added to face powders over the years. These include metallic powders (mica, aluminium, and bronze) to give gold, silver and other metal effects; synthetic bismuth oxychloride and synthetic pearl pigments to give the powder a pearlescent sheen; and various forms of resins and plastics.

See also: Pearl Essence

Colour control was a major problem for cosmetic chemists. Women expected their powder shades to remain the same batch after batch and would change brands if they found too much fluctuation from one purchase to another. In the past the colours were checked by eye using samples taken during the milling process which were compared to a reference powder kept on file. The introduction of colour measurement by colorimeter greatly improved the accuracy of this procedure.

Accurate measurement of colour can only tell you when things go wrong or right. The secret to producing powders of a consistent colour was standardisation. Standardisation of raw materials, proportions, moisture content manufacturing, storage and packaging was the only way to produce consistent results (Wells & Lubowe, 1964), p. 223).

See also: Colour Matching

Manufacture

The method used to make early loose face powders depended largely on the size of a company’s operation.

The traditional method for making face powder on a small scale was to mix the perfume and colours separately in portions of the powder until each was evenly distributed, then combine the perfume mixture and the colour mixture with the rest of the powder base, mix well and sift.

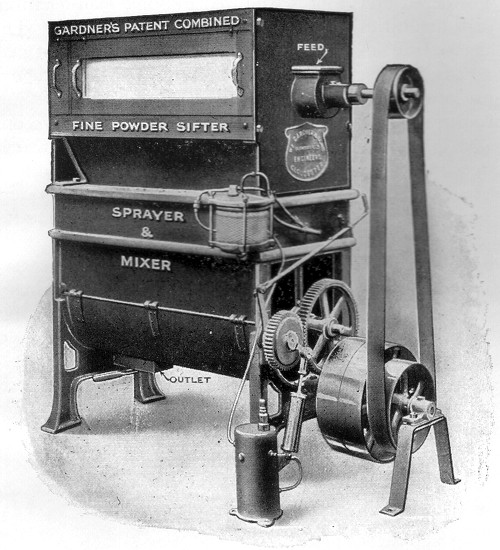

Above: Early powder mixer (Poucher, 1932).

Firms that had larger production runs usually divided the process into two separate stages; first making the powder base and then producing all the colours in the range. Dividing the procedure like this allowed for greater flexibility of production, sped up the manufacturing process and improved quality control.

In the manufacture of face powders on the large scale powder sifter and mixing machines provided with spray arrangement for the perfume addition are used. Where that is not applicable a large wood bin divided into two equal parts of about 3 to 4 ft. square is most handy. The mix is made in one side, sifted into the next, then sifted back again into the just emptied side, and so on. The colours are first ground down in a mortar thoroughly with a small portion of the inert powder and gradually diluted out to a few pounds. The perfume is mixed in the same way with another portion of the powder, unless the spray is used as with the machine. The whole is then thoroughly mixed and sifted at least three times through a fine sieve of 120 hole, a medium size nail brush being the handiest for rubbing through the sieve; finally the whole is sifted through a larger holed sieve, 30 or 40, twice, because the fineness of the sieve previously used to ensure that the degree of fineness necessary, has a tendency to separate the particles, yielding a powder unevenly mixed. In the case of machine-made powder the rotary motion of the lower part as the powder is brushed mechanically through the sifter part guards against that uneven mixing. In making the better class powders they are usually made white in bulk quantity by machine, and then coloured in smaller quantity, finely sifted, and then loosely sifted to ensure thorough mixing, as required.

(Odoro, 1923, p. 443)

Advances in manufacture

Early powders were crude by today’s standards and were rather rough on the skin. By the end of the 1930s this situation had changed due to the introduction of new technologies which produced finer powder particles, improved colouring and more homogeneous mixtures.

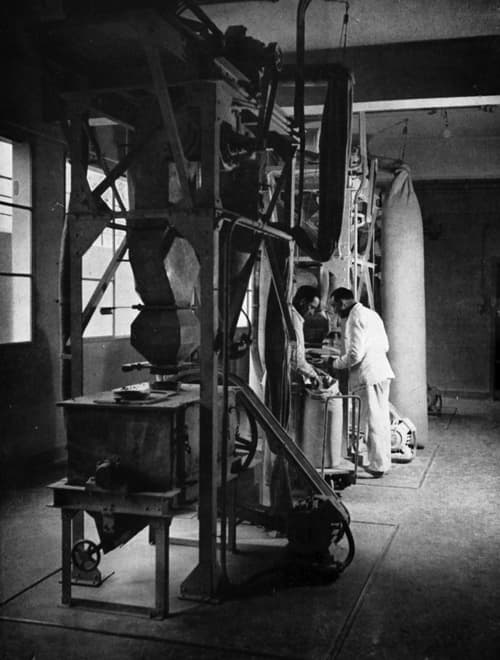

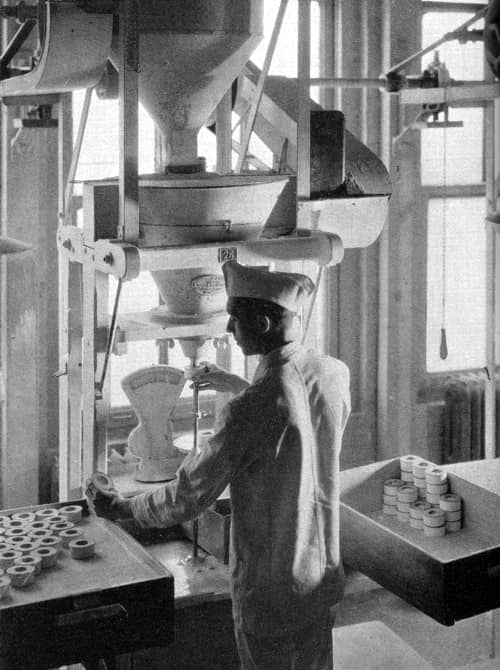

Above: 1939 Grinding powder in a Coty factory.

Some of the advances that helped this process included: improvements in grinding and mixing machines; the use of precipitated powders which were purer, had smaller particles and were consistent from batch to batch; the increased use of proprietary powder bases; developments in technologies that enabled individual base powder particles to be colour-coated, thereby ensuring a more even colour distribution; and the use of new materials such as plastics.

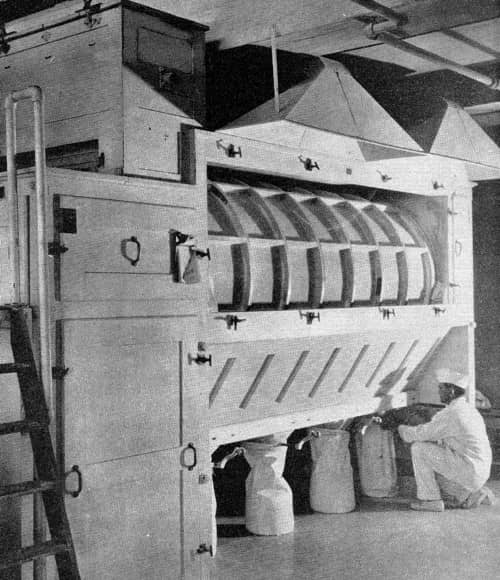

Above: Face powder mixer with dust extractor (Thomssen, 1947).

See also: The Bite Test

Loose powder containers

Early loose powders were packed in simple, cardboard boxes with a tight lid to stop moisture getting in and powder seeping out. As anyone who has opened an old powder box will know, these had a tendency to spill powder every time they were opened. The boxes were not meant to dispense powder as it was expected that women would transfer the powder into their own container on their dresser or vanity table.

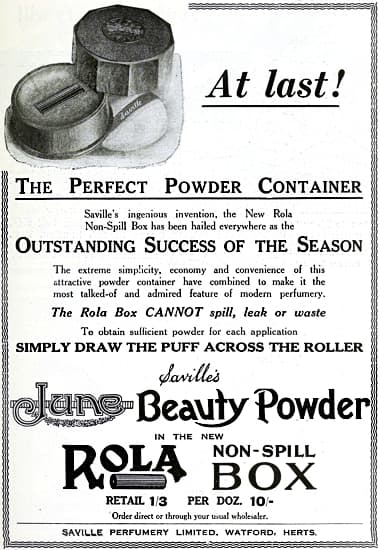

Early attempts to solve the spilling problem saw some manufacturers put the powder into a removable sachet bag contained in the box. Covered in boxes were also made so that the user had to remove a thin covering of paper under the lid to get access to the powder the box contained. This prevented spilling in the shop but the customer could not see the colour and had to turn the box over to determine the colour shade stamped on the back. After moisture-proof Cellophane was developed in 1927, some manufacturers fitted the paper cover with a little circular Cellophane window, or replaced the cover entirely with Cellophane to enable the powder to be seen in the box.

Above: Filling powder boxes (Thomssen, 1947).

All these loose powder boxes suffered from one major drawback; they were meant to be dispensed on a dressing table and were not designed to be carried around in handbags. Although there were alternatives, this problem saw a number of women shift to compressed powder compacts when they were out-and-about.

See also: Compressed Face Powders

Unfortunately, early compressed powders also had their limitations and a number of loose powder containers made from leather, silk and other fabrics were developed to solve the problem of portability.

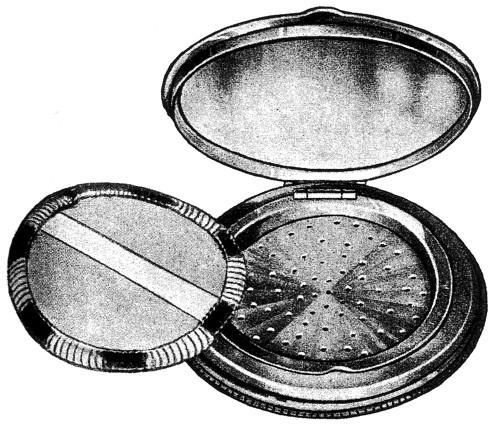

Above: A leather ‘Beaverpuf’ loose powder container for the handbag or purse from the 1920s or 1930s. The lid also served as a powder puff.

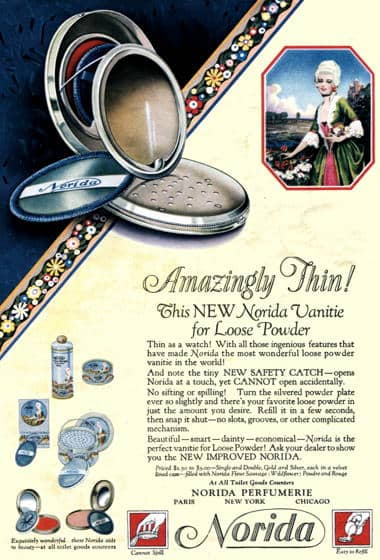

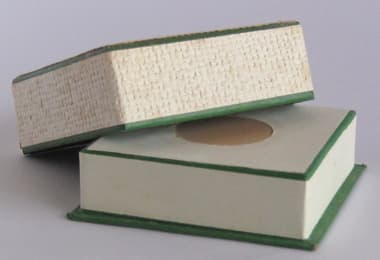

As with compressed powders, the most important loose powder containers were compacts, most of which were variations on a theme. The base of the compact was divided into two parts: an upper compartment that held the powder puff, and a lower compartment to hold the loose powder. The two compartments were separated by a sifter perforated with small holes or slits. Powder was ejected through the holes – so that it could be picked up by the puff – either by tapping the sifter plate or by some other mechanical action (Redgrove, 1933).

Above: 1933 A ‘Badoura’ Sifter Box from the Impex company. The sifter could be lifted to add more powder while the puff helped seal the holes and reduce spillage when the compact was opened.

At first the sifters were metal with only a few holes which made them rather inefficient. These were later replaced with mesh sifters made from fabric that worked a good deal better. Developments in sifters, along with better container seals, eventually made carrying loose powder in a compact almost as convenient as using compressed powder. However, anyone who has used one of these loose powder compacts cannot fail to see why women preferred the pressed cream powders that were introduced after the Second World War.

Using face powder

There were occasional lessons mentioned in beauty manuals about applying powder but the product did not get as much attention as other cosmetics like eye make-up, rouge and lipstick. The main concern was colour, with women encouraged to make sure that they selected a shade appropriate for their complexion.

The Art of Powdering

Powder, like the bloom of a peach, should be a delicate, filmy covering to deep, glowing colouring beneath. Only too often powder gives the effect of a thick, dead coating, from which spring startling patches of colour.

Powder can work magic to the most unbecoming complexion, but like magic, it must be handled with care. Before using powder at all, be sure that it is the right texture and weight for the skin. The fair, dry skin needs as light a powder as can be obtained, and one with a slightly oily base which will cling to the skin, despite its fineness.

The greasy skin calls for a heavier powder with astringent qualities to dry the excessive natural oil.

The fine skin should be powdered with a light swansdown puff; the greasy skin with lambswool. Better than either is ordinary cotton-wool for the first application of powder and puffs for smoothing and blending.

The shade of powder is of primary importance. The powder for day-time will look dull and heavy under electric light. Evening powder should be a shade lighter than that used for street wear.

It may be necessary to blend one or two powders together before skin tones are matched. Many manufacturers are only too pleased to carry out this little personal service for their clients, either by sending sample ranges of powders or by personal application at their depots.

The right shade and texture of powder chosen, the next item is to transfer some of the contents to the face. Dip the puff lightly into the powder and tap gently on the nose, cheeks, forehead and chin. Take a little more powder and blend the areas together. Powder under the chin and around the neck.

With a soft brush, remove the surplus powder and give a final dusting-over with the empty puff. Smooth the fingers lightly over the face with–the only time the movement occurs in beauty work–a downward movement. The reason for this action is to smooth down the tiny hairs or minute particles of skin which have been raised by the working of the puff.

The skin should now present a smooth clear appearance and light renovations can be carried out by means of a little cotton wool. When powdering for evening wear, start on the neck, arms and shoulders first, working up to the face last. …

Never powder over a dirty skin or one which is perspiring. The dirt will cause spots to appear while the dry powder on the moist skin will form into patches and streaks, at the same time forming an excellent basis for enlarged pores. If the face is hot or dirty, wipe it over with a little diluted eau-de-Cologne, complexion milk, or ordinary cow’s milk. A quick application will not remove all the make-up if carried out carefully, but the powder will settle over the cool skin with no harmful results.

If the face is apt to flush and become very red, try using a green powder. It will not look so startling as it may sound, and is an excellent way of concealing a red nose or the tiny red veins which sometimes appear under the skin.

Experiments with two shades of powder on the face sometimes have pleasing results. If, for instance, the cheeks are too full, a darker shade on them than upon the rest of the countenance detracts the attention.(Bradstock & Condon, 1936, pp. 174-176)

Decline

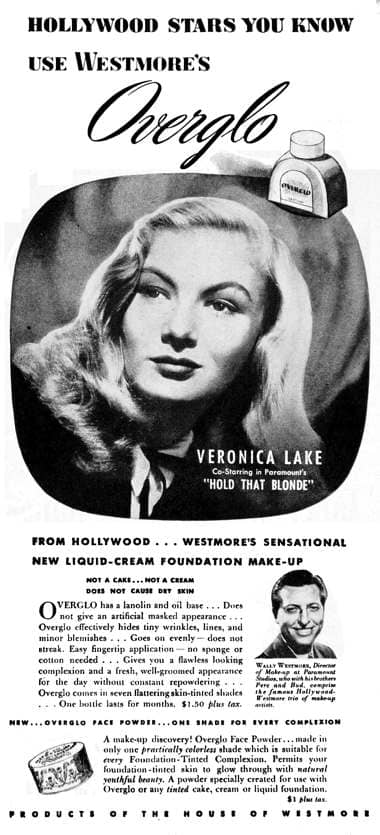

The predominance of loose face powders began fade after the Second World War as cake make-up, liquid foundations, pressed cream powders and other forms of make-up made the use of loose face powder largely redundant. Some manufacturers responded by making their loose face powders translucent so that its primary purpose became simply to make the face look matt and/or reduce shine or later to do the opposite and give the face a glow. The first of these, as far as I know, was Westmore’s Overglo Face Powder, a non-colouring, face powder introduced in 1944.

Above: Westmore Overglo Face Powder. A colourless face powder designed to be used over a coloured foundation.

See also: House of Westmore

The use of loose face powders declined after the Second World War but in recent times they have undergone a resurgence thanks to the ability of cosmetic manufacturers to make very fine mineral powders. These work as an all-in-one concealer, foundation and powder, and are clearly a type of loose face powder even though they are applied with a brush rather than a puff.

First Posted: 25th May 2009

Last Update: 6th May 2021

Sources

The art of beauty. (1825). London: Knight and Lacey.

Bradstock. L., & Condon, J. (1936). The modern woman: Beauty, physical culture, hygiene. London: P. R. Gawthorn Ltd.

Chilson, F. (1934). Modern cosmetics. New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

Corson, R. (1972). Fashions in makeup: From ancient to modern times. London: Peter Owen.

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston: D Van Nostrand Company.

deNavarre, M. G. (1975). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd ed., Vol IV). Boston: Allured Publishing Company.

deNavarre, M. G., & Maicki, R. J. (1938). The new face powders. The American perfumer. February, 33-34.

Face powder and rouge. (1885). The Daily Reporter. June 4th.

Kalish, J. (1944). Face powder. The Drug and Cosmetic Industry. 55(6), 664-666.

Lucas, E. W. (1914) Toilet powders and lotions. The Perfumery and Essential Oil Record. July, 280-284.

Mann, H. (1912). Toilet Powders. The American Perfumer and Essential Oil Review. September, 161.

Martin, J. R. I. (1957). Face powders. In R. Sagarin (ed.) Cosmetics: Science and technology (pp. 222-248). New York: Interscience Publishers.

Mazuyer, G. L. (1910). Face powders. The American Perfumer and Essential Oil Review. December, 226-227.

Mazuyer, G. L. (1911). Face powders. The American Perfumer and Essential Oil Review. January, 240-242.

Murrell, W. (1897). Report on an examination of “face powders.” The British Medical Journal. March 6, 602.

Odoro. (1923). Face powders and talcums. The Perfumery and Essential Oil Record. December, 442-446. London: G. Street & Co., Ltd.

Poucher, W. A. (1928). Modern face powders. Chemist and; Druggist June 30, 810-812.

Poucher, W. A. (1932). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps, Vols. 1-2 (4th ed.). London: Chapman and Hall.

Redgrove, H. S. (1933). Recent developments in loose powder containers. The manufacturing chemist. London: Miller Freeman.

Silman, H. (1936). Face powder manufacture. The Perfumery and Essential Oil Record. March, 102-106. London: G. Street & Co., Ltd.

Thomssen, B. S. (1947). Modern cosmetics (3rd ed.). New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

The toilette of health, beauty, and fashion. (1832). London: Wittenoom and Cremer.

Wells, F. V., & Lubowe, I. I. (1964). Cosmetics and the skin. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation.

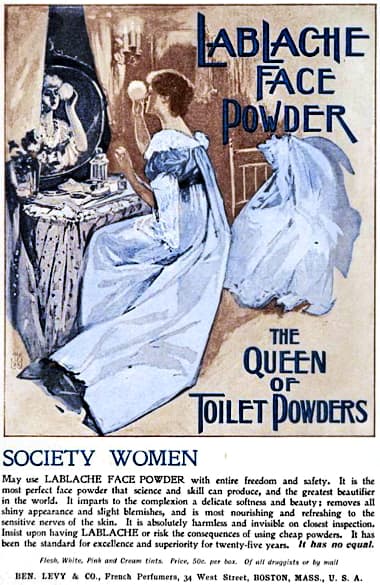

1896 LaBlache Face Powder in four shades: Flesh, White, Pink, and Cream.

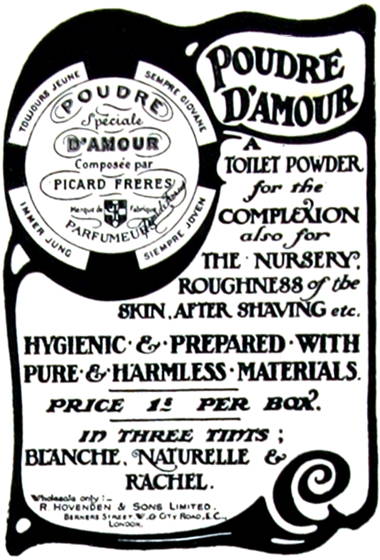

1903 Poudre D’Amour.

1917 Tetlow Pussywillow Face Powder.

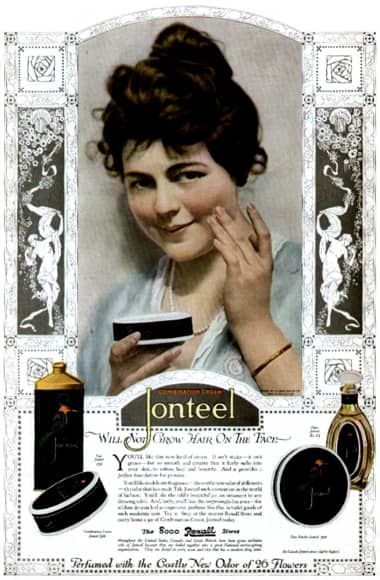

1919 Jonteel Face Powder.

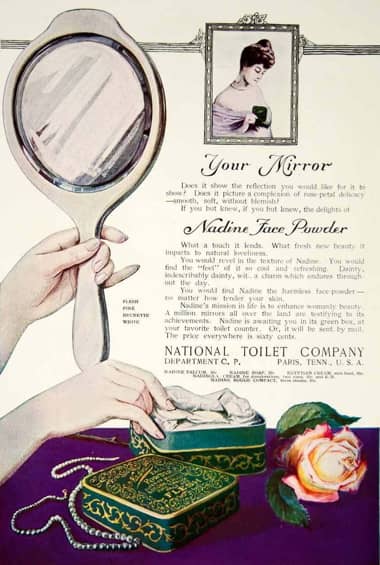

1920 Nadine Face Powder.

1920 Pierrette Face Powder.

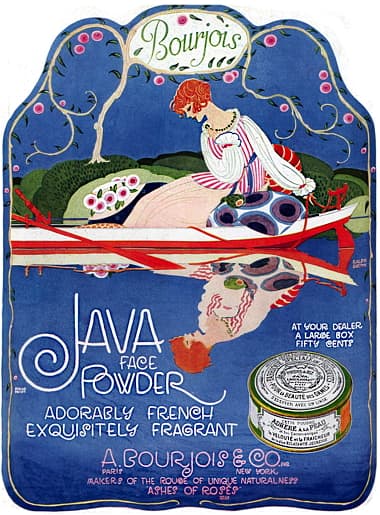

1920 Bourjois Java Face Powder.

1921 Freeman’s Face Powder.

1921 Rigaud Face Powder.

1923 La May loose powder compact with sifter.

1924 Colgate face powder with puff.

1927 Norida loose powder compact with sifter.

1928 Rosine Face Powder in 10 shades.

1929 Richard Hudnut Poudre LeDébut

L. T. Piver Poudre Matité sans talc (without talc). Many powder manufacturers went to great lengths to make their cardboard powder boxes look attractive.

1929 Mello-Glo Face Powder.

1931 Seventeen Face Powder, perfume and compact.

1932 Rola Face Powder. An attempt to fix the powder spilling problem.

1933 Yardley Face Powder, English Peach shade.

1933 Guerlain Shalimar Powder scented with Shalimar perfume.

1934 Coty perfumes and face powders. Each perfume and matching face powder used a different design.

1935 Max Factor Face Powder.

1939 Dorothy Gray Portrait Face Powder.

1944 Elizabeth Arden Face Powder.

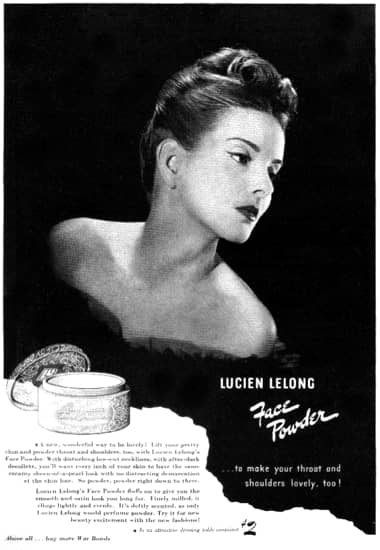

1944 Lucien Lelong Face Powder.

Evelyn Astrova powder box with cover to prevent spilling.

Jane Seymour powder box with opening to see the powder shade.

Do’Orsay powder box with clear cover.

Kathleen Court powder box in bakelite.,

1945 Westmore Overglo Liquid Make-up and Overglo Face Powder.

1946 Revlon Wind-Milled Face Powder.

1947 Icilma Face Powder.

1947 Bourjois Face Powder. Part of a matching range of cosmetics all scented with Evening in Paris perfume.

1948 Dubarry Perfumery Face Powder.

1949 Helena Rubinstein Silk Screen Face Powder.

1951 Charles of the Ritz – Made to order face powder.

1952 Lady Esther Face Powder.

1954 Germaine Monteil Face Powder.

1955 Poudres de Lanvin.