Pan-Cake Make-up

In its day, Pan-Cake make-up was the most successful line produced by Max Factor. Although released as a general make-up, it was originally created to overcome the make-up problems associated with Technicolor film.

Technicolor

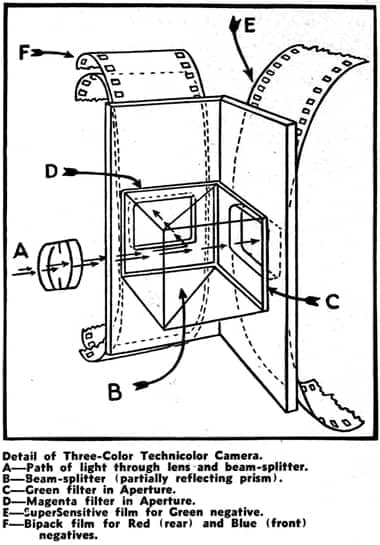

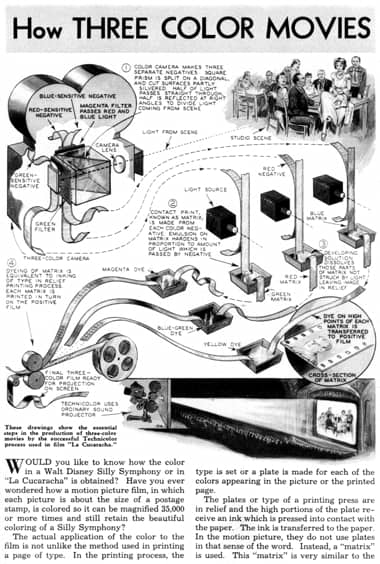

First used in 1916, Technicolor’s evolution had been patchy, and it was only when Technicolor Process 3 was developed in the late 1920s that it began to gain any traction with the Hollywood studios. A number of films were made using the new process but the Great Depression caused the Hollywood studios to cut back on the production of Technicolor films until after 1932 when a new three-color movie camera – known as the three-strip or Technicolor Process 4 camera – was developed. This camera simultaneously exposed three strips of black-and-white panchromatic film to record red, green and blue light on three separate negatives. These were then combined to produce a full-color projection print.

The introduction of any new film stock – such as panchromatic film – created technical problems that had to be solved before the film stock was widely adopted – one of which was make-up. For Technicolor, these problems were further complicated by the introduction of sound in 1927 which required the noisy arc lamps to be replaced with quieter tungsten lamps.

See also: Panchromatic Make-up

When Technicolor began to be widely used by the studios, the make-up used in films was primarily greasepaint and powder. Despite its excellent qualities – such as its ability to hide facial skin flaws in ‘close-ups’ – greasepaint had one fatal failing when it came to colour film.

As its name suggests, light entering Technicolor three-strip cameras was split into three, so brighter lights were required to enable enough light to fall on the red, green and blue negatives. In the brighter lights, the slight sheen greasepaint left on the skin reflected colours from the surrounding scenery so that actor’s faces collected a noticeable tinge from colours near to them on the set. Film stars knew about this issue and many refused to appear in Technicolor films.

See also: Greasepaint

Elizabeth Arden

The developers of Technicolor were well aware of the sheen make-up problem. John Hay ‘Jock’ Whitney [1904-1982], a major investor in Technicolor, appears to have discussed the issue with his racetrack friend, Elizabeth Arden [1881-1966]. In 1935, she purchased the DeLong Laboratories and Make-up Studio in Hollywood and used it to establish the Screen and Stage division of Elizabeth Arden. The Nuchromatic make-up Arden acquired when she purchased DeLong was used in two Whitney backed Technicolor films, ‘A Star is Born’ (Selznick International Pictures, 1937) and ‘Nothing Sacred’ (Selznick International Pictures, 1937).

See also: Arden Screen and Stage Make-up

Max Factor

Max Factor was also looking for a better solution to the Technicolor make-up problem than the greasepaint line his company had developed for Technicolor Process 3 in the late 1920s.

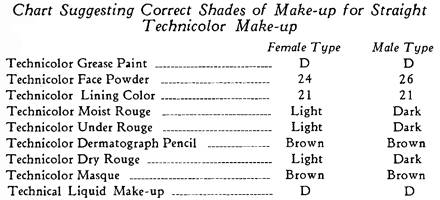

Above: 1930 Chart for Max Factor Technicolor Process 3 make-up. The range consisted of Technicolor Grease Paint, Face Powder, Lining Color, Moist Rouge, Under Rouge, Dermatograph Pencil, Dry Rouge, Masque and Liquid Make-up (Factor, 1930, p. 171).

In the late 1930s, after nearly two years of experimentation, both at the Max Factor laboratory and at Technicolor, a new make-up – known in development as the T-D series – was created. Frank Factor [1904-1996] was put in charge of the project as his father, Max Factor [1872-1938], had been badly injured when he was hit by a delivery truck on Highland Avenue in 1936; an accident that probably contributed to his death two years later.

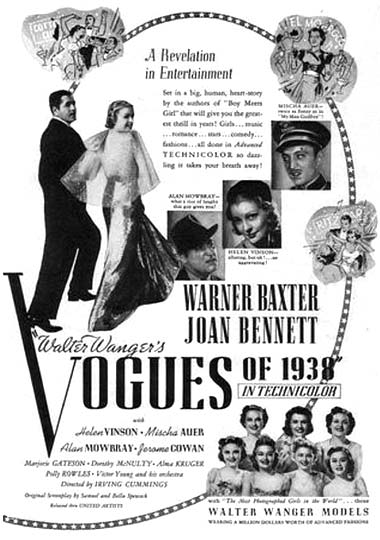

The first commercial use of the new make-up – later trademarked as Pan-Cake – occurred in the 1937 Technicolor Process 4 film ‘Vogues of 1938’ (Walter Wanger Productions). The new make-up was very successful and was soon embraced by the studios, displacing any chance Nuchromatic make-up had of being widely adopted; Arden shut down the Stage and Screen division at the end of the decade.

Cake make-up

Pan-Cake was the product that defined what came to be called cake make-up. It was water-based, containing a highly pigmented powder incorporated into a dehydrated cream made from triethanolamine stearate (a soap), lanolin and water, so can be regarded as a dehydrated powder cream.

See also: Powder Creams

It was manufactured by adding fillers (e.g. talc) and pigments (e.g. iron oxides) to oils and waxes that had previously been mixed in water with the aid of a dispersing agent. After blending the mixture into an even paste, it was dried and then pulverised into a fine powder. As the pigment particles had absorbed the oils and waxes they were now water repellent, a quality they retained when pressed into cakes.

According to Basten, the name ‘Pan-Cake’ came from the fact that the product was a cake make-up sold in a pan (Basten, 2008, p. 112), i.e. it was a pan (made) cake. However, given that all compressed powders were made in pans (godets), that the make-up was originally developed for Technicolor which used panchromatic film, and that the Max Factor Company also released ‘Pan-Stik’ make-up in 1947, it seems more likely to me that the ‘Pan’ was short for panchromatic.

See also: Compressed Face Powders

Ingredients

The finished cake was said to contain the following components:

Parts by weight Oils and waxes 2.8 Plasticizing and dispersing agents 5.3 Pigments 13.3 Talc 78.6 Procedure: An emulsion is prepared; fillers and pigments are added. The mixture is passed through a colloid mill, dried and formed into cakes.

(deNavarre, 1962, p. 948)

As Pan-Cake was water-repellent it would resist perspiration like greasepaint, something that was essential under the hot lights used in Technicolor films and, being matt, it solved the light-reflection problem. An additional bonus was that it took less time to make actors up using Pan-Cake than greasepaint.

The selection and proportion of the ingredients used to make Pan-Cake was very important. The oils and waxes determined the degree of matt or shine the powder had on the skin, and the emulsifying agents, powders and pigments affected the covering power of the film, its thickness, and how easy it was to apply and remove (Wells & Lubowe, 1964). The proportions of pigment colours also required some adjustment. Previous combinations of reds, yellows and whites looked unnatural in Technicolor, so new blends had to be developed with the aid of a spectroscopic analysis of the skin (Baston, 2008, p. 112). This technique was not something particular to Max Factor; other cosmetic companies had been scientifically analysing skin tones for years and adding blues and greens to powders.

See also: Complexion Analysers (Dermoscopes)

Dry method

The manufacturing method used to make the original Pan-Cake – later known as the wet method – was quickly superseded by the dry method. This used a higher proportion of powder-to-emulsion and, rather than mixing all the ingredients together into a paste and then drying and pulverising them, sprayed the binders, oils and other liquid components onto the powdered pigments and fillers as they were blended. The damp powder was then passed through a sieve to remove clumps before being compressed. This method removed the need to dry and pulverise the paste, dramatically reducing the time it took to make Pan-Cake and lowered its manufacturing cost.

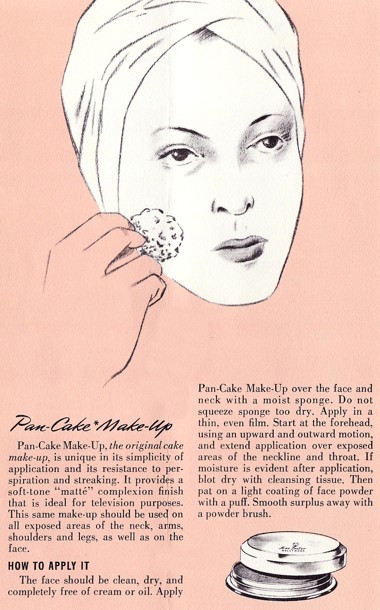

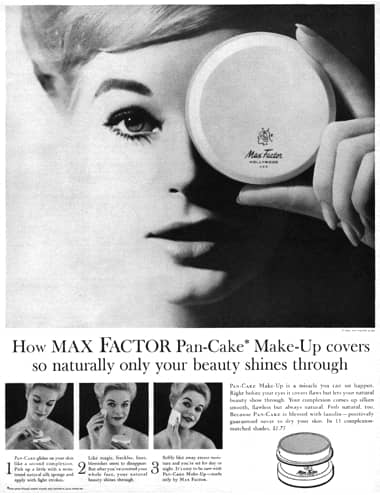

Using Pan-Cake

Applying Pan-Cake required a moist applicator such as a sponge. The moisture in the sponge reconstituted the liquid form of the make-up, which then dried on the skin to form a film of water-repellent powder. Its use required some training as Pan-Cake tended to show streaks that were difficult to smooth over. Product directions suggested smoothing out the make-up with the sponge or the tips of the fingers while it was still wet.

How to apply pan-cake

The correct application of pan-cake is very important. You can create a satin smooth skin texture, using it properly; or, if applied haphazardly, destroy the skin tone.

Saturate a sponge with water and squeeze out the surplus. Rub it over the pan-cake and apply it to the face. Spread over as large an area as you can before adding more pan-cake to the sponge. In this manner you will not run the risk of getting pan-cake on to heavily.

Cover the eyelids, blend carefully into the corners of the nose, mouth, eyes, and between the eyebrows. Blend well into the throat and back to the ears. When you have applied sufficient pan-cake, turn the sponge to the unused side and with a delicate pressure, blend outward from the centre of the face to insure an even distribution of the film of make-up. Allow it to dry. To speed up the process of drying, absorb the moisture with a tissue by blotting.

When the pan-cake is completely dry, powder by patting over the entire face with a puff. Turn the puff to the clean side and lightly buff the face. This will remove surplus powder and pan-cake and leave the face feeing relaxed and smooth as satin. It will also alleviate the feeling of “drawing” the skin that you sometime experience as the moisture evaporates.(Westmore & Westmore, 1947, p. 81)

The sponge could also be used to control the amount of make-up to be applied.

For older women or for people who do not like a heavy make-up appearance I would suggest to have the sponge quite wet, holding a great deal of water, then take a little of the cake and apply it to the face still holding an excess of water in the sponge, leaving the face wet. Then remove the excess of water from the face by patting a dry towel of facial tissue. This will definitely leave a more natural appearance. Here, you see, we have diluted the cake evenly, an effect which is hard to acquire by using a little cake make-up and trying to smooth and smear it all over the face.

(Macias-Sarria, 1944, p. 48)

The Max Factor company did not recommend using Pan-Cake in isolation. On normal or dry skins it was to be applied over Invisible Make-Up Foundation – a form of vanishing cream developed around the same time as Pan-Cake – while individuals with oily skins were recommended to use Astringent Foundation – originally called Honeysuckle Skin Cream.

Max Factor did not suggest powdering after the Pan-Cake was applied.

You apply it … by using a moistened sponge or cotton. Start applying Pan-Cake Make-Up to the forehead, using an outward and upward motion; then continue in this manner until the face is completely covered with Pan-Cake-Make-Up … using it very, very sparingly. Then absorb any excess moisture by blotting with a Kleenex tissue. Then use your Face Powder Brush to remove any surplus Pan-Cake Make -Up, and to ensure an even, smooth finish.

(Lecture for Max Factor Hollywood, 1940, pp. 2-3)

However, face powder could be used if a matt finish was required.

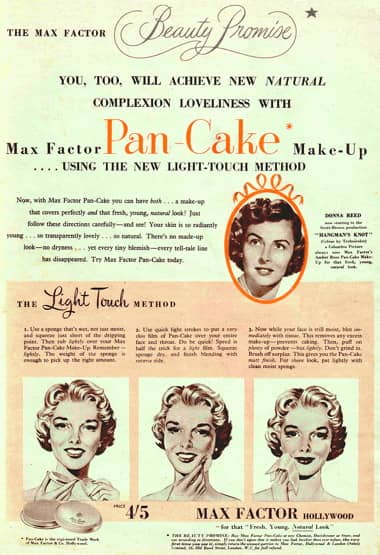

The Light Touch Method

1. Use a sponge that’s wet, not just moist, and squeeze just short of the dripping point. Then rub lightly over your Max Factor Pan-Cake Make-up. Remember—lightly. The weight of the sponge is enough to pick up the right amount.

2. Use quick light strokes to put a very thin film of Pan-Cake over your entire face and throat. Do be quick! Speed is half the trick for a light film. Squeeze the sponge dry, and finish blending with the reverse side.

3. Now while your face is still moist, blot immediately with a tissue. This prevents any excess make-up—prevents caking. Then, puff on plenty of powder—but lightly. Don’t grind in. Brush off surplus. This gives you the Pan-Cake matt finish. For a sheen look, pat lightly with a clean moist sponge.(Max Factor advertisement, 1953)

Sales

According to Basten, the models used on the set of ‘Vogues of 1938’ appropriated large amounts of Pan-Cake for their own use. However, they soon found that off the set the colours were too dark. Max Factor was against selling it to the general public but his son, Frank Factor, had other ideas. As it took some time for the necessary shades to be formulated, Pan-Cake was not released as a general make-up until February 1938, coinciding with the release of ‘The Goldwyn Follies’ (Samuel Goldwyn Productions), the second Technicolor film in which it was used.

Commercially the product was a tremendous success for Max Factor. Income from Pan-Cake would soon outstrip the combined revenues of all other Max Factor cosmetics (Basten, 1995, p. 161) and this led to the release of similar products by other cosmetic companies. For example, in 1942, Elmo released Photo-Finish; Frances Denney, Over-Tone; Daggett & Ramsdell, Debutant; Louis Philippe, Angelus; and Campana, Solitaire. Although Frank Factor had taken out patents for the formulation of Pan-Cake (US: 2,034,697 & US: 2,101,843), most of these new products went unchallenged.

About three years ago when dry cake make-up grew up to become one of the most important make-up items, cosmetic manufacturers began to call on their chemist to create something that would not infringe on the patent. But it was at that time, too, that another California company put their dry make-up on the market. Everybody waited for a law suit to follow; it never came (gossiping comments all gave the same reason, although this reason has never been published). This left the door open to other manufacturers.

(Macias-Sarria, 1944, p. 47)

See also: Frances Denney and Elmo

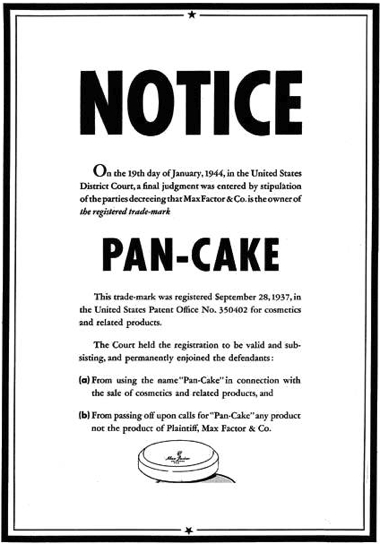

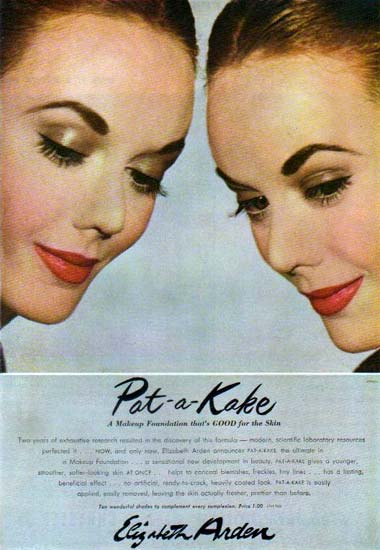

The Max Factor company showed more concern about its Pan-Cake trade-mark, even going as far as posting notices in trade journals warning other companies about trademark infringement for the use of the name. The company also took legal action where it thought it was necessary; for example it forced Elizabeth Arden to replace its ‘Pat-A-Kake’ (1945) with ‘Pat-A-Crème’ (1948).

See also: Elizabeth Arden (post 1945)

Other formulations

It was relatively easy to formulate a cake make-up that was sufficiently different from the Max Factor patents to avoid problems.

[M]any manufacturers told their chemist to formulate something new and different which would not infringe on the patent.

The first thing was to review the raw materials which the patent didn’t include in its exhaustive list. In addition there were new ingredients and here I give a brief account of the same:

For alkaline bases we have: Triisopropanolamine; the aminoglycols, etc.

For binders we have, instead of quince seed mucilage, the following much superior ones: Methyl cellulose, aluminium gels, sorbitol borate, potassium caseinate and casein derivative binders, glyceryl borate, sodium alginate, methacrylate gums, etc.

For plasticizers instead of diethylene glycol, we now have propylene glycol which I mention alone for its safety and for its pharmaceutical endorsement.

In the patent formula, we can dispense very well with beeswax (now we have synthetic waxes) and cetyl alcohol and replace their presence with stearic acid or any fatty acids.(Macias-Sarria, 1944, p. 47)

There was therefore plenty of room for cosmetic chemists to develop their own forms. Indeed, some companies, such as Helena Rubinstein, took out additional patents to cover their own types of cake make-up.

See also: Cake Make-up

As well as being widely emulated, the success of Pan-Cake had a profound effect on the cosmetics industry in other ways. Pan-Cake started a revolution in the way women used make-up and also accelerated research by cosmetic companies into other products with similar functions. This research helped develop the wide range of new foundation creams, liquid foundations and pressed cream powders that appeared after the Second World War.

Decline

Although Max Factor still sells Pan-Cake today, the excitement over cake make-up did not long outlive the 1940s and probably only lasted as long as it did due to the restrictions of the Second World War. It remained popular with some younger women but older women, with reduced oil in their skin, found Pan-Cake rather drying and were much happier with the newer pressed cream powders and liquid foundations – with their higher oil content – that became popular after the war. Frank Factor – who changed his name to Max Factor Jr. after his father’s death – was well aware of this issue and developed Pan-Stick and Cream-Puff make-up in 1947 and 1953 respectively. Although Pan-Cake’s use as a general consumer make-up declined after the war, the Max Factor company still promoted it for other uses, such as television make-up.

See also the company booklet: Television Make-up for Black-and-White and Color

First Posted: 12th December 2011

Last Updated: 17th March 2023

Sources

Basten, F. E. (1995). Max Factor’s Hollywood. Glamour, movies, make-up. Los Angeles: General Publishing Group.

Basten, F. E. (2008). Max Factor: The man who changed the faces of the world. New York: Arcade Publishing.

deNavarre, M. G. (1962). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd. ed., Vols. I-IV). Orlando: Continental Press.

Lecture for Max Factor Hollywood art school of make-up [Booklet]. (1940). Los Angeles: Sales Builders, Inc.

Macias-Sarria, J. (1944). Process of manufacturing cake make-up. Perfumery & Essential Oil Review. November, 43-44; Dec, 47-48.

Factor, M. (1930). The art of motion picture make-up. In Hall, H. (Ed.). Cinematographic Annual (Vol. 1) (pp. 157-171). Hollywood: The American Society of Cinematographers.

Stull, W. (1935). Explanation of the trichrome Technicolor. American Cinematographer. January, 8-9, 12, 14.

Wells, F. V., & Lubowe, I. I. (1964). Cosmetics and the skin. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation.

Westmore, E., & Westmore, B. (1947). Beauty, glamour and personality. New York: Prang Company.

Wilkinson J. B., & Moore, R. J. (Eds.). (1982). Harry’s cosmeticology (7th ed.). New York: Chemical Publishing.

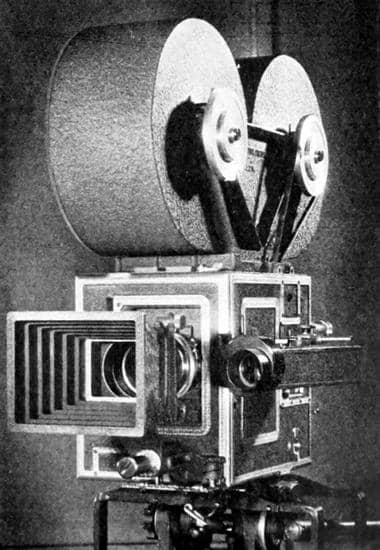

Technicolor Three-Color Camera.

Detail of the Three-Color Technicolor Camera (American Cinematographer).

1935 Part of a ‘Modern Mechanix’ article about Technicolor film showing how a three-strip or Technicolor Process 4 camera recorded red, green and blue light on three separate panchromatic negatives.

1937 Poster for the ‘Vogues of 1938’ movie filmed in Technicolor Process 4.

1938 Publicity shot of Joan Bennett and other actresses in ‘Vogues of 1938’ using Max Factor rouge, powder and lipstick. Pan-Cake could not be included as it had not yet been released for general consumption.

1939 Make-up charts using Pan-Cake.

1940 Max Factor Pan-Cake make-up.

Max Factor Pan-Cake from the 1940s.

1944 Notice in the trade journal ‘The Drug and Cosmetic Industry’ warning of trademark infringement for the use of the name Pan-Cake.

1945 Max Factor Pan-Cake. Shades included Cream No. 1, Cream-Rose, Cream No. 2, Amber No. 1, Amber-Rose, Amber No. 2, Natural No. 1, Natural-Rose, Natural No. 2, Tan No. 1, Tan-Rose and Tan No. 2.

1946 Elizabeth Arden Pat-A-Kake. It was applied with a pad soaked in Ardena Skin Lotion. Max Factor took issue with the name and forced Arden to remove it from sale.

1947 Mixing Pan-cake.

1952 Max Factor Pan-Cake make-up.

1952 Max Factor Pan-Cake make-up (France).

1953 Max Factor Pan-Cake make-up.

1958 Applying Max Factor Pan-Cake make-up.

1959 Max Factor Pan-Cake make-up.

1960 Max Factor Pan-Cake Make-up.