Greasepaint

By the 1840s, most theatre stages in the western world had adopted gas lighting in preference to candles or oil lamps. Gaslight was brighter, made the stage more visible and could be dimmed with taps through a gas table. However, the brighter gaslight was not without its problems; it showed up shoddy costumes, sets, and theatre interiors, and made many existing stage techniques unusable. Actors were also flooded with light which some players considered very unsatisfactory.

Our modern stage system, however, is opposed to the exhibition of facial expression. There is such a flood of light, and the face is so bathed in effulgence, from above and below, that there is little relief. There are no shadows. The eye is distracted by the general garishness. As it is said, “you cannot see the wood for the trees,” so here you cannot see the face for the light. Now, under the old dispensation, there was a better system: the light was furnished by four [candle] chandeliers, which hung over the actors’ faces; the rest of the stage was in comparative shadow mystery, and the figures and faces stood out with a sort of brilliancy. Thus it will be seen how the eye was concentrated on the central objects, because it had nothing else to attract or distract it.

(Fitzgerald, 1892, pp. 32-33)

As brighter lighting became more common, actors were forced to change the way they dressed, acted and used make-up. The old powder make-up did not cope well with the new lighting conditions – which washed colour from the face – but there was no viable alternative until commercial greasepaint became available in the 1870s. Some actors stayed with powder after greasepaint was introduced but by the 1890s – when major theatres had installed even brighter electrical lighting – greasepaint had become an essential component of an actor’s toolkit.

Grease-paint

The use of greasy substances in western theatrical make-up goes back to at least the eighteenth century when W. R. Chetwood (1749) described the use of ivory-black mixed into grease for blackening the face. It was removed with fresh butter. ‘The Oxford Companion to the Theatre’ suggests that when gas lighting was introduced, a number of actors mixed powered mineral pigments with some form of grease to produce a grease-based make-up. For example, Fitzgerald (1901) describes how the actor Herman Vezin [1829-1910] “mixed a lot of colour with melted tallow in Philadelphia in 1857”. William (‘Willy’) Clarkson [1861-1934] – an infamous London wigmaker – also suggested that Vezin was “if not the first, [then] one of the first to make up with grease” on the London stage. However, it was Ludwig Leichner who first commercialised the idea.

Ludwig Leichner

Leichner was an opera singer with an interest in chemistry so was in an ideal situation to advance the cause of stage make-up. After developing a viable product, he established a commercial powder and make-up business in Berlin in 1873 and, within a short time, was selling his products internationally.

The ‘grease paint’ Leichner developed had a greater covering power and intensity of colour than the old powder make-up and gave actors more control over how it was applied. Skin tones, shadows and highlights were easier to create so, when correctly applied, greasepaint enabled actors’ faces to look more natural and be more expressive in the brighter light; in short, they looked more lifelike. The make-up was also largely unaffected by the perspiration generated under the hotter gaslights.

The old method of making up was not by any means so effective as the preparation of the present day—the face being treated to a coating of violet powder, the hare’s foot and rouge were called in to throw up the complexion, the chin and cheek bones being very liberally treated to colour. It will be seen at once that this method needed reformation, for it is impossible to give the whole of the face a natural hue with violet powder, and though carmine was employed to heighten effects, the face must have had a patchy appearance.

Another difficulty, and a very serious one, was the perspiration of the flesh becoming, after a little exertion, palpable through the make-up. This frequently resulted in one colour running into another, hence a most ludicrous expression. It is almost (even now) impossible to effectually patch up a make-up after it has been once laid on the face, and the old method necessitates the actor making up afresh after he has strutted and fretted through a few scenes.(Harrison, 1882, pp. 24-25)

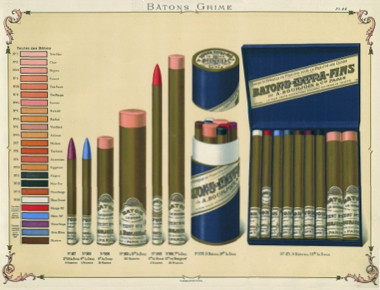

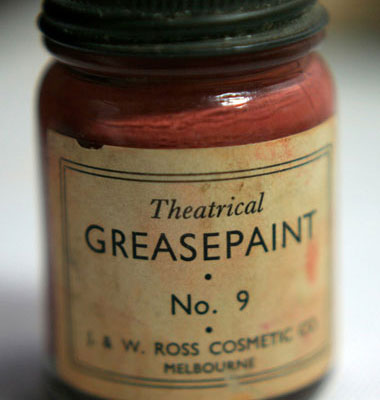

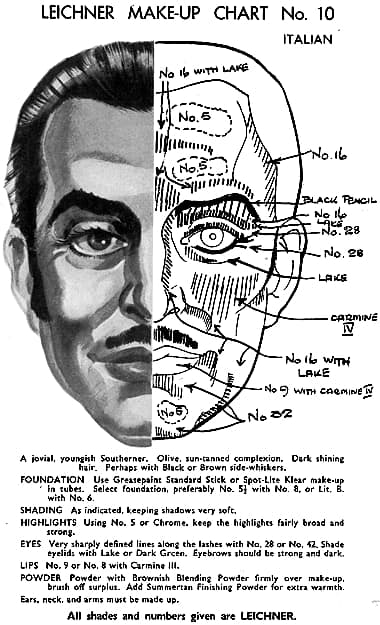

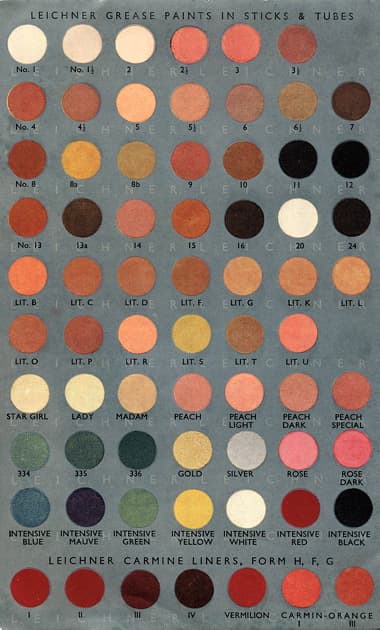

Leichner’s greasepaint came in a range of colours that were numbered for easy reference, starting with No. 1 as the lightest, a scheme also followed by later manufacturers. The sticks came in a range of sizes; thicker sticks for the base or foundation, and thinner sticks – known as liners – for shadowing, highlighting, age lines, veins, eyebrows and other features.

See also: Leichner

Wig-Paste

Some authors refer to greasepaint as a modified form of wig-paste or joining paste – a product used to conceal the join of a wig. The reason for this is probably due to Carl Baudin of the Leipzig State Theatre, Germany. He commercialised a flesh-coloured paste made of zinc, ochre and lard – which makes it a type of greasepaint – that he had developed to conceal the joint between his wig and forehead.

The prepared chalk, fuller’s earth, powdered blue, rouge, carmine, burnt cork, camel’s-hair brush, hare’s-foot, and one or two dry paints which in the old days formed the stock-in-trade, no longer suffice for present requirements; elaborate grease paints have completely supplanted them, except, perhaps, in the portable theatre.

These grease paints are identical with the composition which formerly went by the name of ‘wig-paste’ whose sole function was to secure an actor’s wig to his forehead and conceal the joining. The flesh-coloured grease paint still performs the same duty; but, like all the other tints—the ‘light-red’ and ‘dark-red,’ employed for heightening the complexion after a paler groundwork has been laid on, excepted—it is known by a number (3), and sold in sticks. Chemists almost everywhere now deal in grease paints.(Wagner, 1899, pp. 155-156)

Composition

Stick greasepaints are produced by mixing dry pigments into a fat/wax base. They were not difficult to make so the idea was widely copied.

Base: A wide variety of fats and waxes could be used in the base including lard, suet, tallow, cocoa-butter, almond oil, castor oil, beeswax, spermaceti, lanolin, paraffin and ceresine. Poucher recommended that up to 10% of the base be made of beeswax and/or lanolin, to make the greasepaint tacky so that powder will adhere to it.

Greasepaints made from a perishable base like lard, tallow and suet were liable to go rancid within a few months without appropriate preservatives. Mineral-based greasepaints, which date back to 1888 at least, were more resilient and had the added advantage that the ‘mineral greases’ did not smell.

A B C D E F Almond oil – – 72 – – – Lard, benzoated – 15 – – – 56 Cocoa-butter – – – 80 80 – Beeswax, white – – 14 – 6 3½ Spermaceti – – 14 – – – Lanolin, anhydrous 5 – – – – – Liquid Paraffin 70 60 – – – 26½ Ceresine 25 25 – 20 14 14½ (Redgrove & Foan, 1930, p. 58)

The sticks had to be firm enough to resist crumbling or breaking but soft enough so that they would spread easily when applied on the skin. Their melting point could not be too high or too low. Poucher warns that if it was below 37°C (blood temperature) the greasepaint would become “fatty after application, and the result will be an unsightly mess necessitating the continuous use of powder” (Poucher, 1930. p. 533). Needless to say it was not possible to make greasepaint that would work flawlessly in all conditions. Actors often needed to warm the sticks before using them in cold dressing rooms and keep the sticks cool in very hot climates.

Colour: The colours used in greasepaint consisted of a white base for covering power and various pigments to produce the range of shades. Typical ingredients used in the white base included zinc oxide, titanium dioxide, chalk, kaolin, talc and bismuth subnitrate.

No. 1638 Zinc oxide. 750 Kaolin. 50 Precipitated chalk—heavy. 200 1000

No. 1638 Zinc oxide. 700 Bismuth subnitrate. 200 Talc. 100 1000 (Poucher, 1932, pp. 534-535)

Colours added to the white base were made to recipes that included pigments such as carmine, ochre, lakes and lampblack.

No. 6 Yellowish Flesh Yellow ochre 10.8 Armenian bole 1.2 White base 88.0

No. 6½ Japanese Dark ochre 12 Burnt umber 4 Burnt sienna 2 White base 82 (Redgrove & Foan, 1930, p. 64)

Quality control was essential to ensure that colours and consistency did not vary between batches.

See also: Colour Matching

Movie make-up

With the introduction of motion pictures, many stage actors began to work in films as well. Unfortunately, early film stocks were not sensitive to the full colour spectrum and this created a number of make-up problems. If actors did not wear make-up when filming they looked dark and dirty but if they did they often appeared to have a white, mask-like look. Although greasepaint continued to be used on movie studio lots, the film medium meant that it underwent a number of changes in its formulation and the way it was used too numerous to mention here.

See also: Early (Silent) Movie Make-up

Cream-paints

Greasepaint was also made as a cream, referred to as cream-paint or ‘flesh cream’ by some. It was produced in a more limited range of tints, initially sold in jars but later in tubes. Cream greasepaint had one major advantage over stick forms: it could be applied more easily when large amounts were needed as, for example, in clown make-up. It also reduced the damaging drag on the skin that can occur when using sticks, which perhaps explains its popularity with many actresses.

These are of a softer consistency than the grease-paints. They are put up in jars, instead of sticks, and are more generally used by women. The effect produced is practically the same as that resulting from grease-paint. The different shades are white, flesh, pink, brunette, deep brunette for dark complexions, also Creole, Gypsy, Indian and other shades, which may be made to order.

(Young, 1905, p. 12)

In 1914, Max Factor developed a cream greasepaint for the motion picture industry. Described as a ‘flexible greasepaint’ it was later marketed as Supreme Greasepaint. Produced in twelve graduated shades, it was initially sold in pots but later switched to collapsible tubes which Factor considered to be more convenient and sanitary (Basten, 2008, p. 46). It could be applied more quickly than, and covered as well as, if not better than stick greasepaint, even though it was laid on more thinly. Max Factor later used it as the base for his Panchromatic Make-up, introduced in 1928.

See also: Panchromatic Make-up

Using greasepaint

Before applying greasepaint, the skin was first prepared by working in an oily or greasy material. This made it easier to work the greasepaint and remove it after the performance. The commonest materials used for this purpose were cocoa-butter, paraffin and cold cream. The early stagers generally recommend theatrical cold cream, as other oils and paraffin were widely believed to stimulate hair growth.

See also: Eyelash Growers

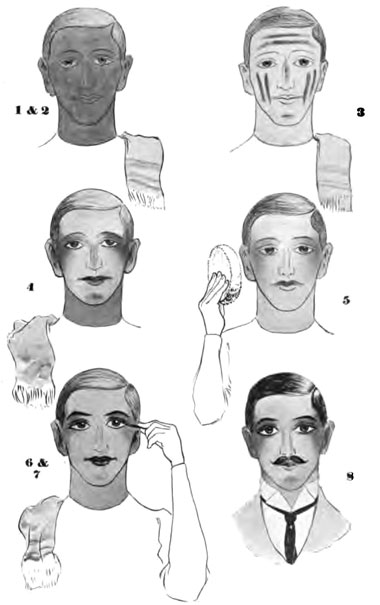

Once the excess oil had been blotted from the face, the flesh-tinted ground colours were applied, followed by the highlights, shadows and other facial features depending on whether the make-up was straight, aged or character. Lips and eyes would need their own treatments. The make-up was usually finished off with powder to tone down colour and reduce shine.

Greasepaint was removed by smearing the face with some form of oily or greasy material such as the previously mentioned cold cream or liquid paraffin which was then wiped off with a towel or, after they were invented, tissue paper. The face was then washed with soap and water and/or wiped with astringent to remove any remaining grease.

As well as being harder to remove, greasepaint was harder on the skin than the older powder make-up. When worn for extended periods during long theatre runs it could generate pimples and rashes in susceptible individuals.

Greasepaint and general cosmetics

For many women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, greasepaint was their first introduction to make-up. It found its way into private homes through amateur dramatics and tableau vivants (poses plastiques) – both popular activities in middle and upper class Victorian and Edwardian society. It was also used by professional photographers to make-up their clients before they took studio portraits – an activity that extended to all levels of society.

Greasepaint was not designed as a general make-up. It did not replaced face powder and rouge but was used by some women as a lipstick, mascara or eyeshadow when such things were not widely available. For example, in a 1959 interview, the seventy-six-year-old actress Estelle Winwood [1883-1984] described how she used greasepaint as a lipstick.

I remember, … it was in New York in 1916 and I was young and pretty then … I use to paint my lips with Leichner’s No. 2 stage makeup. It was used in the Theatre for rouging your cheeks you know—and it was considered very terrible for wearing it offstage.

(“Bumper Film Book,” 1959, p. 95).

For young actresses the temptation to use greasepaint off the stage must have been very strong and when they did they stretched the boundaries of what was considered acceptable. Where they led others followed.

First Posted: December 27th 2010

Last Update: 20th September 2020

Sources

Bamford, T. W. (1946). Practical make-up for the stage. Theatre and stage series. London: Pitman & Sons.

Basten, F. (2008). Max Factor: The man who changed the faces of the world. New York: Arcade Publishing.

Bumper film book. (1959). London: Spring books.

Chetwood, W. R. (1749). A general history of the stage, from its origin in Greece down to the present time. With the memoirs of most of the principal performers that have appeared on the English and Irish stage for these last fifty years. London: W Owen.

Cooley, A. J. (1866). The toilet and cosmetic arts in ancient and modern times with a review of the different theories of beauty and copious allied information social, hygienic, medical. New York: Burt Franklin.

Fitzgerald, P. (1892). The art of acting in connection with the study of character, the spirit of comedy and stage illusion. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

Fitz-gerald. J. S. A. (1901) How to make-up. A practical guide for amateurs etc. London: Samuel French.

Harrison, C. (1882). Theatricals and tableaux vivants for amateurs giving full directions as to stage arrangements “making up,” costumes, and acting. London: Upcott Gill.

Hartnoll, P. (Ed.). (1967). The Oxford companion to the theatre (3rd ed.) London: Oxford University Press.

Poucher, W. A. (1932). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (4th ed., Vols. 1-2). London: Chapman and Hall Ltd.

R. B. (1850). The perfumer’s legacy or companion to the toilet containing a treatise upon the human hair; directions for its culture, preservation, and embellishment; and advise upon the use of the most superior hair-dye. London: Kent and Richards.

Redgrove, H. S., & Foan, G. A. (1930). Paint, powder and patches: A handbook of make-up for stage and carnival. London: William Heinemann.

Wagner, L. (1899). How to get on the stage and how to succeed there. London: Chatto & Windus.

Wells, F. V., & Lubowe, I. I. (1964). Cosmetics and the skin. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation.

Young, J. (1905). Making up. A practical and exhaustive treatise on this art for professional and amateur. New York: M. Witmark & Sons.

Ludwig Leichner [1836-1912].

1887 Advertisement for theatrical electric lighting

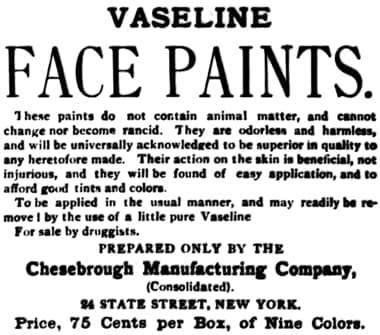

1888 Chesebrough Manufacturing Company, the makers of Vaseline introduce a petroleum-based greasepaint. The company stopped advertising it after 1890.

“The Chesebrough Manufacturing Company are reported to have supplied a long-felt want in the shape of vaseline face paints, which do not contain unguent matter, and cannot change nor become rancid. These paints are odorless, and the manufacturer claims superior in quality to any heretofore made, while their action on the skin is beneficial and they are easily applied. The Chesebrough Manufacturing Company are well-known makers of vaseline for which they have a world-wide reputation. The face paints are for sale by all druggists” (New York Dramatic Mirror, 1888).

Batons Grime (Stick Make-up) from an 1898 Bourjois catalogue.

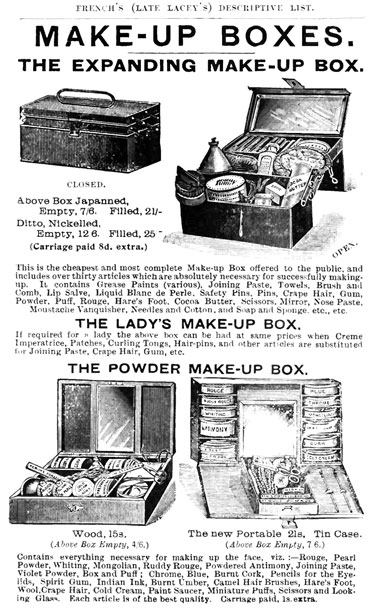

1901 French’s greasepaint and powder make-up boxes which provides a good indication of the materials provided in, and the differences between, male and female greasepaint kits.

1902 Actor making up in a dressing room. He appears to be applying a false nose. Note the banks of electric lights around both the mirror in front of him and the larger one on the wall.

1904 Actress applying stick greasepaint.

1905 Diagrams showing how to apply straight make-up for a young man using greasepaint.

c.1938 Leichner stick make-up. Note the thick and thin forms and the wax paper covering which was peeled off in use.

Stein’s greasepaint sticks in cardboard containers. Enclosing the greasepaint in this way helped reduce breakage.

A cream greasepaint in a glass jar made in Melbourne, Australia.

Max Factor Supreme Greasepaint in tubes sold as part of a student make-up kit.

M. Stein’s chart for Lining Colors, Grease Paints and Face Powders.

1937 L. Leichner.

Leichner Make-up Chart No 10 – Italian.

1938 Part of a Leichner colour chart for Greasepaints in sticks and tubes.