Water Cosmetique (Mascaro)

Given that ‘rimmel’ means mascara in Turkish, Farsi and several European languages, it is sometimes said that Eugene Rimmel [1820-1887] was the originator of mascara. However, the product he made, Superfin Water Cosmetique, was developed to be used on men’s moustaches not women’s eyelashes. This means that modern mascara started its life as a men’s, not a woman’s, cosmetic.

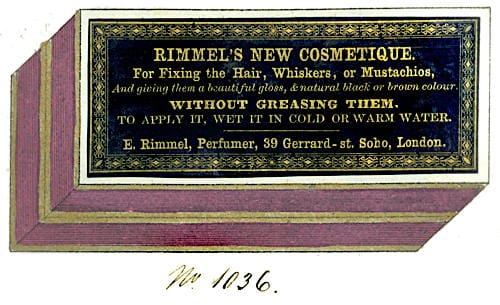

Above: c.1860 Rimmel New Cosmetique. My guess would be that the box contained a block of cosmetique and a brush.

Moustaches

Moustaches and beards were very fashionable in the nineteenth century and there was a wide variety of products used by men to shape and style them. As grey often appeared on beards and moustaches before it affected head hair, some men used colour to hide the white hairs in their facial hair. As well as the more permanent dyes there were a number of cosmetics that could be used to temporarily stain it, including pomatums, pomades and water cosmetiques.

Pomatum: Coloured stick pomatums (also known as ‘batons’ or ‘lévres’) were a combination of suet and wax.

Pommade Hongroise: Made using lead oxide boiled with olive oil.

Both products were used to fix moustaches in place but, if required, could be coloured with lamp-black or umber to hide grey as well.

Water Cosmetique: A water-based mixture of pigment and soap whose sole function was to act as a hair colourant. The pigment was first mixed with a little water then milled into the soap. It was sold in two main forms: as batons/sticks which were smeared over wet hair and then touched up with a moustache brush; and blocks which were applied with a wet moustache brush. The first form continued to be made during the twentieth century and was sold as hair sticks; the second would go on to become the basis of cake/block mascara.

Black and Brown Cosmetique

Such as is sold by RIMMEL, is prepared with a nicely-scented soap strongly colored with lamp-black or with umber. The soap is melted, and the coloring added while the soap is soft; when cold it is cut up in oblong pieces.

It is used as a temporary dye for the moustache, applied with a small brush and water.(Piesse, 1857, p. 225)

Beard-coloring

[Can] be made by melting 20 parts of soft soap on a water bath, and adding to it 1 part of gum Arabic dissolved in 2 parts of water. The colouring for brown is fine mahogany-brown with a little drop-black, and the latter alone for black. The colouring must be finely comminuted, and well mixed with the basis. The preparation may be perfumed with a sufficiency of the following mixture after it cools:—

French Geranium Oil 20 parts Oil of Bergamot 10 parts Oil of Cloves 15 parts Cedar-wood Oil 2 parts Form the colouring into sticks about 3 in. long, and ¾ in. in diameter.

(Year-book of pharmacy, 1892, p. 252)

Each of these products – pomatums, pomades and water cosmetiques – had their drawbacks and critics. Although more susceptible to perspiration than pomatums or pomades, water cosmetique was easier to remove, would not go rancid, and could be used when men did not want their hair to look waxed.

The hair, or portions of it, particularly that of the face, is sometimes temporarily darkened by what may be called “painting” it. This is done by smearing a black or coloured stick of hard pomatum or cosmetique over it until the desired colour is given to it, and then slightly diffusing the colour over the surface with the brush. The practice is a dirty and unnatural one, as the colour is partially removed by everything it touches, and the moustache or beard is converted by it into a trap to catch the dust. It is only to be tolerated when occasionally used by the fastidious to conceal a few straggling gray or faded hairs. Its use, like that of false moustaches and whiskers, once so common, is now chiefly confined to fashionable fops, and to the “swells” and “gents” of low life.

(Cooley, 1866, p. 270)

Petrolatum cosmetiques

As a side note I should mention petrolatum-based cosmetiques. These were made using petrolatum (petroleum jelly) by the Chesebrough Manufacturing Company, the American Oil Company and others. Chesebrough’s product was called Vaseline Cosmetique and American Oil’s was marketed as Densoline Cosmetique. Densoline Cosmetique was sold in sticks wrapped in silver paper but Vaseline Cosmetique was sold in tubes suggesting it was more like an ointment or cream. Unlike water cosmetiques, petrolatum-based cosmetiques would not run at the first sign of perspiration. Little is known about these products but it is likely that they were also used as temporary hair stains.

See also: Chesebrough Manufacturing Company and Greasepaint

Theatre make-up

Male actors were big users of cosmetiques as they often needed to temporarily change the colour of their hair, eyebrows, moustaches and beards when disguising their age, their character, or blend their own hair colour with that of a wig or hairpiece. In the past, Indian or Chinese inks had been used, but by the end of the nineteenth century actors could select from a range of products to colour their head and facial hair including greasepaint, powder, pomatums, pomades and water cosmetique. I can find no reference to petrolatum cosmetiques being used in the theatre but this is not surprising as actors already had greasepaint which was also impervious to perspiration.

If it is desired that the young actor should wear his own hair it can easily be dressed, or the colour may be altered by the use of powders, which can be removed again by brushing lightly. But generally speaking the amateur had better depend upon the wig and the wig-maker to gain his effects. However, the hair can be made to appear white or grey as required with a little care, some powder and grease paint, the whole being carefully brushed and combed with a very fine comb. In regard to wigs we have already given full particulars. When we come to the eyebrows, the beard, and the moustache we have a much easier task. It stands to reason that the hair on the face can be lightened or darkened according to desire by the judicious use of the various colours in grease. A slight moustache may even be painted out by soaping or sticking it down with Pomade Hongroise, and colouring it to match the complexion. But the process is not recommended, and the idea that a very large or heavy moustache can be obliterated by this means is absolutely erroneous. But most moustaches of ordinary dimensions can be made to disappear by French’s—Moustache Vanisher. In this way you slightly cover it with spirit-gum and paste down with No. 2½. Color according to character required. This is most efficacious and is quite reliable. In darkening a moustache care should be taken to avoid smearing the under part of the nose or the cheeks. Black or Brown grease paint or cosmetique should be used. A dark moustache can be lightened by painting it with grease paint of the right tint and a dexterous use of a fine-toothed comb. Powder easily afterwards. Any shade can, indeed, be secured by using the right colour grease paint and by powdering. The beard and whiskers may be treated in the same way.

(Fitz-Gerald, 1901, pp. 85-86)

Mascaro

When water cosmetique was used in theatrical make-up it was often referred to as mascaro. Originally made only in black and brown the colour range was later extended to include white to add grey to an actor’s hair.

Mascaro or Water Cosmetique—For darkening the eyebrows and moustaches without greasing them and making them prominent. A most useful article. It can be applied by wetting in cold or warm water.

(Fitzgerald, 1881, p. 124)

Eyebrows and eyelashes

Male actors could also use make-up to colour their eyebrows and eyelashes. In the past, men had used small brushes obtained from wigmakers to apply stains and/or waxes to moustaches and the same type of brush was now employed by them to apply water cosmetique (mascaro) to their eyelashes.

With regard to the eyes, their appearance may be greatly improved by the steady use of a thin camel hair pencil, a narrow streak of watercolour being solidly drawn directly under the bottom eyelash; for the top eyelashes the better mode is to darken them with a particular brush, which can be obtained from Clarkson’s, Wellington-street, Strand, or any wigmaker’s. It is really a toothbrush on a diminutive scale. If for a dark complexion it should be well soaked in Indian ink or sepia. This brush should also be used for darkening the eyebrows, as the paint does not clog, and consequently gives them a realistic effect.

(Harrison, 1882, p. 25)

The practice of using water cosmetique (mascaro) was not universal as personal preferences differed. If stage performers coloured their eyelashes at all – rather than just drawing a line under them with pencil or brush – they could select from a range of materials and techniques with many preferring black or brown greasepaint liners over water cosmetique (mascaro).

Take a small artist’s stump of leather or paper, the end being covered with black grease-paint, melt very slowly over the gas or candle, then apply to the upper and lower lashes. It will adhere and quickly harden. It is much better to use a soft stump than a lining stick, for by some accident, or through nervousness, it may strike the eyeball. Also be careful not to melt the paint too much or it will be almost sure to fall upon the eye. This frequently happens, is very painful, and in several cases has resulted seriously [sic.]. Use the black lining grease-paint for this purpose, not the black cosmetique.

(Young, 1905, pp. 60-61)

See also: Eyelash Beading

Both water cosmetique (mascaro) and greasepaint had their advantages and disadvantages. Greasepaint was a bit riskier, was affected by heat and required more skill to apply but made the lashes glossy. Water cosmetique (mascaro) was easy to apply with a small brush and, although not affected by heat, perspiration would make it run. In addition, being made of soap it stung if it got into the eyes.

Actresses and other female performers also used eye make-up. Personal preference would determine whether they used water cosmetique (mascaro), greasepaint or some other material such as kohl.

See also: Kohl

Mascaro/mascara

By 1900, eye make-up was being used outside of the theatre. Some women used it only to accentuate their eyebrows but others were darkening their eyelashes and the area around the eye as well. This practice had been going on for some time in France. The court of Napoleon III was known to use make-up more liberally than elsewhere and there are suggestions that the fair-haired Empress Eugénie used pigment to accentuate her eyes. Where she led others followed.

French cosmetic manufactures sold blocks of water cosmetique (mascaro) for the theatrical trade packed into small, rectangular boxes each with a small mirror and brush. These could be carried in a purse, so when the practice of darkening eyebrows and/or eyelashes became more popular in the twentieth century, the invention was widely copied and became the commonest way that mascara was packaged for at least half a century.

Sometime before 1910, water cosmetique (mascaro) also began to be called mascara, the masculine ending ‘o’ being replace with the feminine ‘a’. The adoption of this term appears to track alongside the increased use of eye make-up by women. Universal acceptance of the term took a long time to complete but was largely achieved in the English-speaking world by the end of the 1930s, with most cosmetic companies falling into line. Some firms held out for longer; Elizabeth Arden for example, still referred to her cake mascara as Cosmetique until 1950. By this time there were a range of mascara formulations on the market and the word had completely lost its relationship with the moustache colourant used by men, becoming instead a generic term used for any pigment applied to eyelashes by women.

See also: Cake Mascara

First Posted: 9th June 2011

Last updated: 1st July 2024

Sources

Cooley, A. J. (1866). The toilet and cosmetic arts in ancient and modern times with a review of the different theories of beauty and copious allied information social, hygienic, medical. New York: Burt Franklin.

Fitz-Gerald, S. J. A. (1901). How to “make-up”. London: Samuel French.

Fitzgerald, P. (1881). The world behind the scenes. London: Chatto & Windus.

Harrison, C. (1882). Theatricals and tableaux vivants for amateurs. London: L. Upcott Gill.

Piesse, G. W. S. (1857). The art of perfumery, and the methods of obtaining the odors of plants, with instructions for the manufacture of perfumes for the handkerchief, scented powders, odorous vinegars, dentifrices, pomatums, cosmetiques, perfumed soap, etc. with an appendix on the colors of flowers, artificial fruit essences, etc. etc. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston.

Rimmel, E. (1855). The book of perfumes. London: Chapman and Hall.

Young, J. (1905). Making up. New York: M. Witmark & Sons.

Year-book of Pharmacy. (1892). London: J. & A. Churchill.

Rimmel Superfin Water Cosmetique (c.1860) sold as a baton/stick. The aluminium container is presumably used to overcome the problem of rusting.

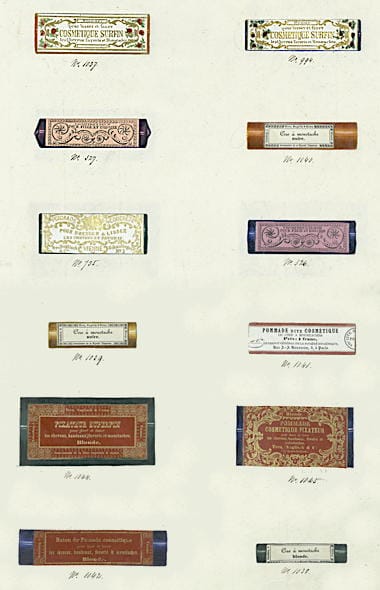

c. 1860 Assorted cosmetiques for the hair, beard and moustache (Vienna).

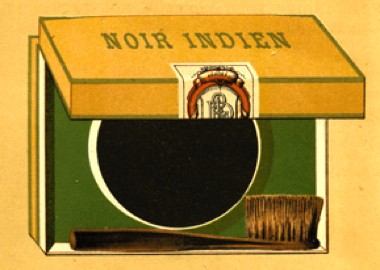

1886 Dorin Indian Black for hair, moustaches and sideburns with brush (Noir Indien pour cheveux, moustaches et favoris avec brosse) from an 1886 catalogue that I assume is a water cosmetique. The tablet is round like a compact rouge rather than the more traditional rectangular shape.

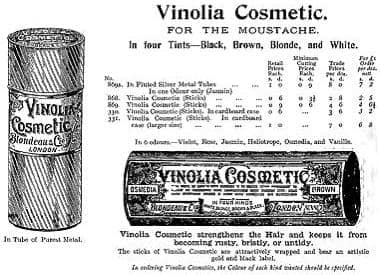

1899 Vinolia Cosmetic for the moustache. It came in a fluted, silver-metal (left) or cardboard case (bottom). Shades: Black, Brown, Blonde and White.

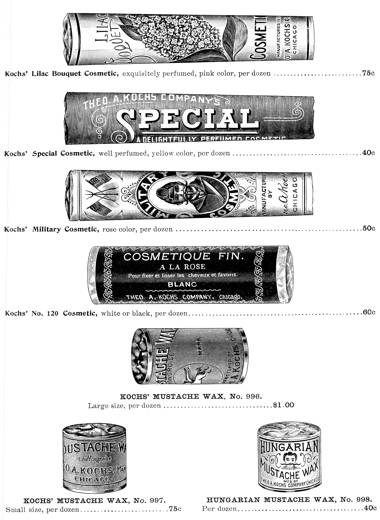

1902 Assorted cosmetiques and moustache waxes from Theo A. Kochs & Sons, New York.

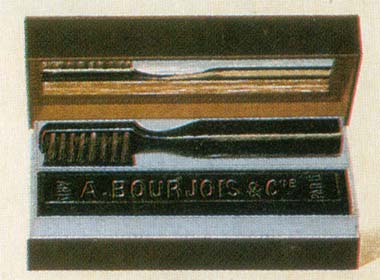

1898 Bourjois Indian Tablets (Tablettes Indiennes) in four shades, from an 1898 catalogue. The designer of this much-copied container, with brush and mirror, is unknown.

Egyptian Cosmetique (date unknown). These cosmetique sticks formed part of a child performers make-up set.

1930 Norma’s Hair Stick. “So harmless the darker shades are a perfect make-up for the eyes, formed for convenience to apply to either the brows, lashes or hair.” Shades: Black, Brown, Medium Brown, Light Brown, Auburn, Golden.

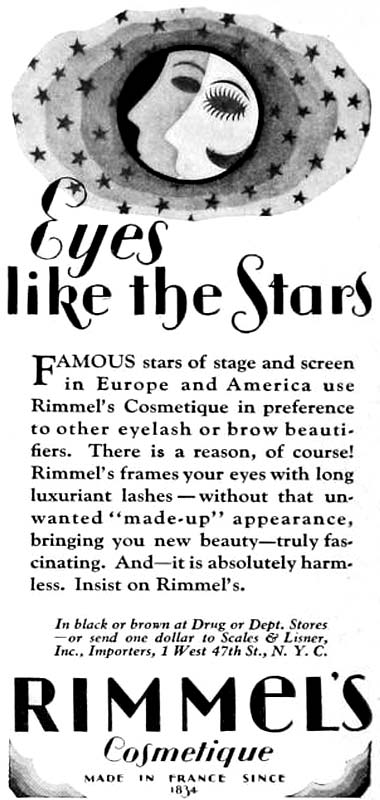

1931 Rimmel’s Cosmetique in black and brown. The “Made in France since 1834” is misleading as that is the date he set up his business to make perfumes.

A box of Rimmel Cosmetique (date unknown) with the standard block, brush and mirror.

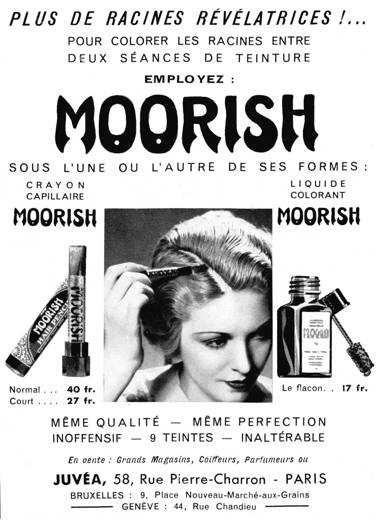

1938 Juvéa Crayon Capillaire (Hair Pencil).

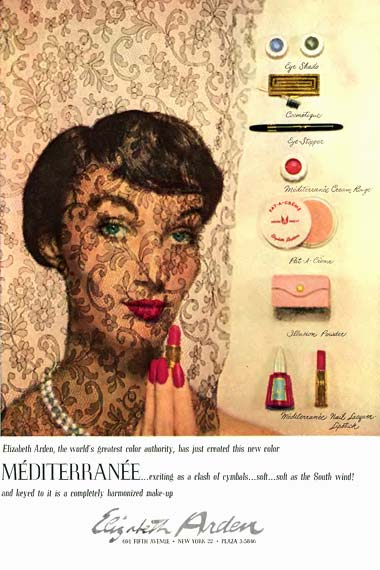

1949 Elizabeth Arden’s Cosmetique along with Eye Sha-do, Eye Stopper and other cosmetics. She adopted the term mascara the following year, possibly the last cosmetic firm to do so.

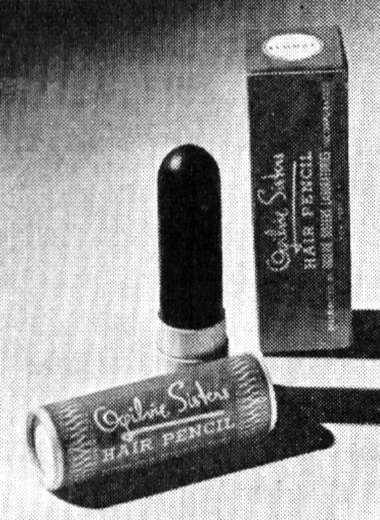

1943 The Ogilvie Sisters Hair Pencil. Described as a “color stick for temporary coloring, not a dye nor a bleach”.

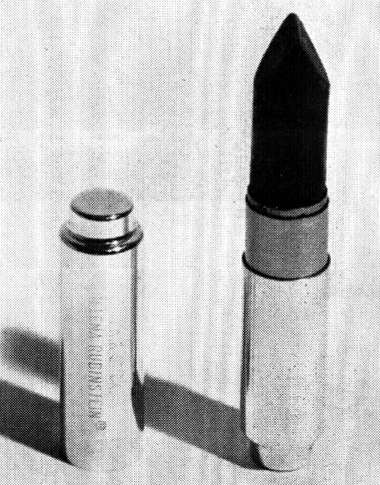

1954 Helena Rubinstein Hair Stick.