Petrolatum/Petroleum Jelly

Robert Chesebrough began selling petrolatum under the trade-name Vaseline Petroleum Jelly in 1871. After a slow start, it went on to become an international best seller. More importantly, it was the first in a long line of petroleum derivatives used in the developing cosmetics industry.

Manufacture

Chesebrough made petroleum jelly by subjecting a residue of West Virginian crude oil – known as rod wax – to a vacuum distillation process to remove the more volatile odoriferous oils, followed by filtration through bone-black.

The manufacture of vaseline is quite simple. When the lighter liquids, gases, etc., of the petroleum oil have been distilled over, the remaining product, the tar, is placed in a large open iron boiler, which is suspended over a hot fire in the open air until deodorized; then it is allowed to cool. In a hot-air chamber (about 50°[C]), arranged in rows, are large inverted tin cones filled with bone-black; upon these the deodorized tar is poured. At the end of a few hours, the tar comes through in a state of “white vaseline;” after awhile, the bone-black becomes partially exhausted, the product is no more “white”, but “blond,” and as the operation progresses, the bone-black becoming weaker in its absorbing powers, the “blond,” passes into a “red.” Thus we have white, blond, and red vaselines. This mode of manufacture constitutes the American process.

(Fougera, 1884)

Although Chesebrough’s method of making petrolatum is no longer used, distillation and filtering still form the basis of the refining process today.

Vaseline

Once Vaseline was established it was widely copied. These petrolatum/petroleum jellies were known as mineral jellies, paraffin jellies and soft paraffins but they were also commonly referred to as Vaseline by nineteenth century chemists, medical professionals and the general public alike, even though they were not made by the Chesebrough Manufacturing Company.

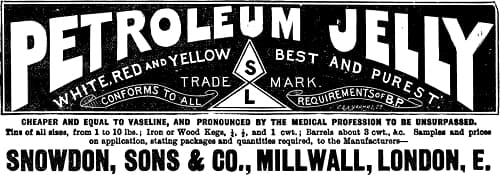

Above: 1893 Petroleum Jelly from Snowdon, Sons & Co.

Chesebrough had trademarked the name Vaseline in the United States, Britain and in a few other countries and, where it could, it vigorously protected any unauthorised use of the name.

See also: Chesebrough Manufacturing Company

Composition

Petrolatum/petroleum jelly consists of solid mineral waxes and liquid mineral oils; however, this wax-and-oil mixture has some surprises. If mineral oil and mineral wax are mixed together, a product similar to petroleum jelly can be made, but it is not a true petrolatum as it will separate over time. In 1925, the chemist Ferdinand William Breth [1887-1957] speculated that a third component was present in petroleum jelly that kept it stable. He extracted the material and called it ‘protosubstance’ (Meyer, 1968). Unfortunately, no amount of the extract would make real petroleum jelly from a mixture of mineral wax and mineral oil so his idea was largely discredited. However, it added to the belief that petroleum jelly is a complex mixture. A case can therefore be made that as petroleum jelly is refined, not made, it is a natural product.

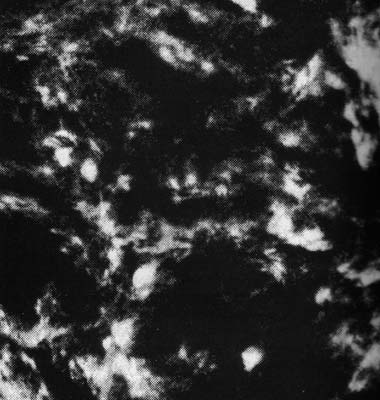

Petrolatum/petroleum jelly is now considered to be a colloidal system made up of a solid phase (mineral waxes) which take up the liquid phase to produce a jelly-like mass. It is important that the raw material from which petroleum jelly is extracted – paraffin-base and mixed-base crudes – are not subjected to intense heat or strong chemicals during refining otherwise the oil-in-wax system will be broken, something Chesebrough must have discovered during the long hours he spent refining it.

The amount of wax and oil varies in different blends of petroleum jelly. Those with higher levels of wax are harder and have a higher melting point, while those with more oil are softer and have a lower melting point. These differences need to be taken into account when petroleum jelly is used in cosmetic formulations, e.g. softer petroleum jelly could be used in skin creams, while a harder petroleum jelly might be used in lip balms.

Characteristics

Petrolatum/petroleum jelly has a number of attributes that make it attractive to cosmetic chemists. It is an occlusive and an emollient and, although very tacky, was used in the past by some women in place of a cold cream, vanishing cream or moisturiser. Chesebrough noted this when he suggested in his 1872 patent that it was good for chapped hands.

The white form is relatively colourless and odourless and will not oxidise (go rancid) over time. This gave it a long shelf life and meant that jars of petroleum jelly could sit in medicine cabinets for years. In the past, ointments, creams and cosmetics were made with fats and oils from plants and animals. As these went rancid, the ointment, cream or cosmetic would change colour, start to smell, cause skin problems and generally become unpleasant, so substituting them for petroleum jelly was regarded as a great improvement.

Preservatives and chemical processes such as hydrogenation, mean that shelf-life is no longer the problem it once was, but in the early part of the twentieth century – when cosmetics began to be mass produced – petrolatum and other petroleum-based ingredients played an important role in enabling cosmetics to escape from being made up locally by a drugstore, chemist or pharmacy. Petroleum-based cosmetics could be stored for long periods of time without deteriorating which meant they could be distributed over wide areas, even to places where the climate was hot; Daggett & Ramsdell’s Perfect Cold Cream being a good example. Economies of scale and other advantages of industrial production also saw costs fall, enabling a wide range of cheap cosmetics to become available.

See also: Daggett & Ramsdell

Petrolatum/petroleum jelly is also chemically inert, which means that most drugs and other chemicals could be mixed with it without any chemical action taking place. This made it an ideal base for ointments and other skin-care products.

Uses

Chesebrough suggested that Vaseline could be used in ‘carrying, stuffing, and oiling all kinds of leather’, as a lubricant, a hair pomade and for chapped hands. It has maintained this diverse range of uses and has also been employed in such things as food production, electrical insulation, rust prevention and paper manufacture. The use to which it was put was partly determined by the level of impurities left behind in the filtration process. White petroleum jelly had low levels of impurities, while red petroleum jelly had higher levels, making it unsuitable for some purposes.

In commerce, three kinds of vaseline are met with, different in color, but similar in properties. White vaseline is generally used internally, for cold cream, certain prescriptions, ophthalmic pomades, etc. The blond vaseline is used in pharmaceutical pomades and ointments, skin diseases, and as a hair-dressing. The red vaseline is used mostly for veterinary purposes and with excellent results; it is also used in making colored ointments and a number of various preparations for the preservation of leather, wood, etc.

(Fougera, 1884)

Medicinally, white petroleum jelly was originally sold for use on cuts and burns, but it was also advertised as a cure for a range of skin problems including: blisters, sores, chaffing and sunburn, for rheumatism and haemorrhoids and, when taken orally, as a cure for colds, sore throats, diphtheria, dysentery and other diseases.

Cosmetic uses

Once white petroleum jelly was introduced into medicine cabinets, women also found a number of cosmetic uses for it, some of which have persisted to this day. It was used on lips to reduce cracking, on eyebrows and eyelashes in the hope that it would ‘make them thicken and grow’, and on the skin to ‘beautify the complexion’.

Cosmetic chemists also used it and similar petroleum-based ingredients in a wide range of products. As well as making soap, Chesebrough also used petroleum jelly to make ‘Vaseline Cold Cream’ and ‘Vaseline Pomade’ for hair. Hair products would prove to be one of the more common early uses of petrolatum where it replaced beef, suet, lard, olive oil, lanolin, cocoa butter and other fats.

Petroleum jelly is much used in pomade manufacture. In fact, petroleum jelly, like all hydrocarbons of like nature, does not turn rancid, and only requires a relatively small amount of aromatic material in order to acquire a very pleasant perfume, and, if a little soft, can easily be hardened by a slight addition of beeswax, or, better still, of ceresine, without modifying the basic products. Further, petroleum jelly is an efficient lubricant and does not mat the hair to the same extent as oxidisable fatty oils; thus its role is clearly defined in this part of the manufacture, and if we do not advise its exclusive use, it is because its action on the hair is not quite the same as natural fats. Petroleum jelly will often appear in the formulae, concurrently with pomade bases, and for certain purposes we shall point out some instances where petroleum jelly is the only vehicle employed.

(Durvelle, 1923. p. 274)

These uses are all relatively simplistic and do not indicate the true importance of petrolatum/petroleum jelly to the cosmetics industry. This would come later when it was incorporated into almost every form of skin care and cosmetic product including: cleansers, skin creams, moisturisers, hand creams, rouge, lipsticks, eye shadows, sunscreens, nail whiteners and deodorants.

Vaseline cold cream White vaseline 2 lbs. Fat-almond oil 1 lb. White beeswax 10 ozs. Bergamot oil 14 drachms. French rose-geranium oil and Turkish rose oil each 20 drachms. (Deite, 1892. p. 331)

Cleansing Cream % U.S.P. Petrolatum 19.0 White Mineral Oil 63.0 White beeswax 6.0 White Paraffin 11.5 Perfume 0.5 Melt the beeswax and petrolatum together; add the white oil; perfume when cool.

(Meyer, 1968)

Paste Rouge % Petrolatum, U.S.P. 77.0 Cetyl Alcohol 3.0 Cocoa Butter 3.0 White Beeswax 3.0 Spermaceti 5.0 Benzoic Acid 0.1 Cosmetic Lake Color 8.0 Perfume 0.9 Melt the ingredients together, mix and mill, adding perfume last.

(Meyer, 1968)

Petrolatum/petroleum jelly has been in continuous use for 150 years. It is low cost, an excellent occlusive and very safe. It remains one of the few cosmetic ingredients that can be sold, used, and kept – pretty much ‘as is’ – in the bathroom cabinet. Recent moves to remove it and other petroleum-based ingredients from cosmetics have little to justify them.

First Posted: 10th August 2011

Last Update: 8th August 2020

Sources

Chesebrough Manufacturing Company. (1884). Petroleum: Its origin, uses and future development. A highly interesting sketch. London: Author.

Chesebrough Manufacturing Company. (1885). Vaseline: Its history, uses and therapeutic value. Also, as a base in official (U.S.P.) and other formulas. Interesting tp physicians, pharmacists, veterinary surgeons, and others. New York: Author.

Deite, C. (1892). A practical treatise on the manufacture of perfumery: Comprising directions for making all kinds of perfumes, sachet powders, fumigating materials, dentifrices, cosmetics, etc., etc., with a full account of the volatile oils, balsams, resins, and all other natural and artificial perfume-substances, including the manufacture of fruit ethers, and tests for their purity. (W. T. Brannt, Trans.). Philadelphia: Henry Carey Baird & Co.

Durvelle, J.-P. (1923). The preparation of perfumes and cosmetics. (E. J. Parry, Trans.). New York: D. Van Nostrand Company.

Fougera, E. (1884). American Druggist. 13, April, 62.

Jellinek, J. S. (1970). Formulation and function of cosmetics (G. L. Fenton, Trans.). New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Meyer, E. (1968). White mineral oil and petroleum and their related products. New York: Chemical Publishing Company.

Schlossman, M. L. (Ed.). (2000-2009). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (4th ed., Vol. III). Carol Stream, Il: Allured Publishing Corporation.

Schueller, R., & Romanowski, P. (1999). Conditioning agents for hair and skin. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Williamson, H. F., & Daum, A. R. (1959). The American petroleum industry: The age of illumination 1859-1899. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

Williamson, H. F., Andreano, R. L., Daum, A. R., & Klose, G. C. (1963). The American petroleum industry: The age of energy 1899-1959. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

Early twentieth century bottle of Vaseline Petroleum Jelly with its suggested range of uses. The cork would be replaced by a screw top in 1908.

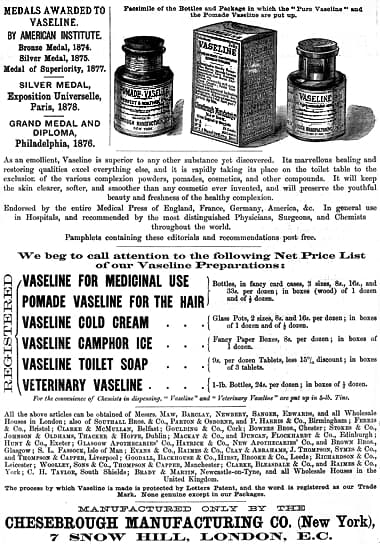

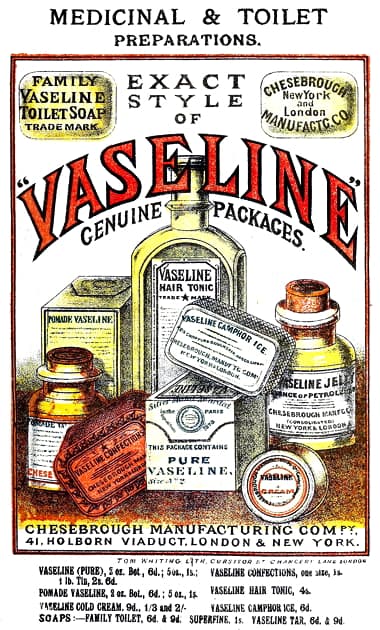

1879 Vaseline products.

Photomicrograph of a high quality petrolatum. The dark areas are mineral oil, the white, mineral wax.

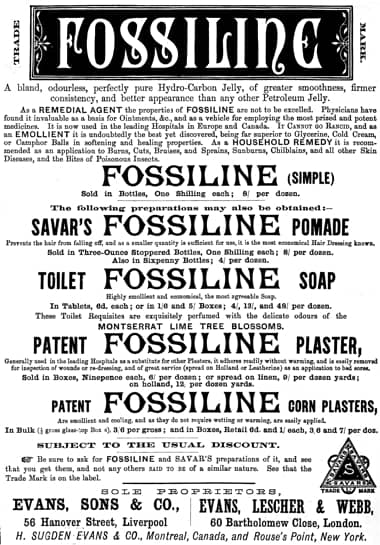

1881 Fossiline Petroleum Jelly.

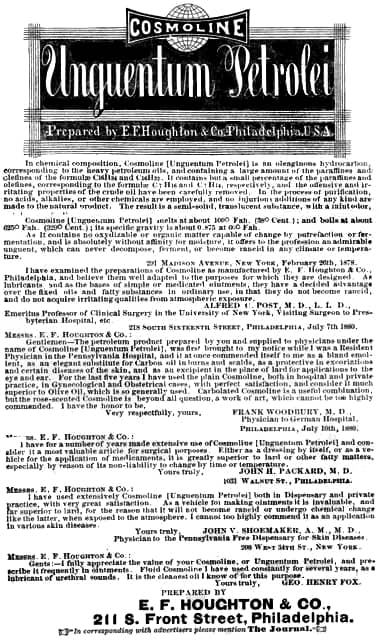

1882 Cosmoline Petroleum Jelly, ‘Unguentum Petrolei’. A form of Cosmoline is still made by Houghton today as a rust preventative. The product may not have been a true petroleum jelly but rather a mixture of ceresine, paraffin oil and paraffin wax (Jellinek, 1970).

1885 Chesebrough Manufacturing cCmpany.

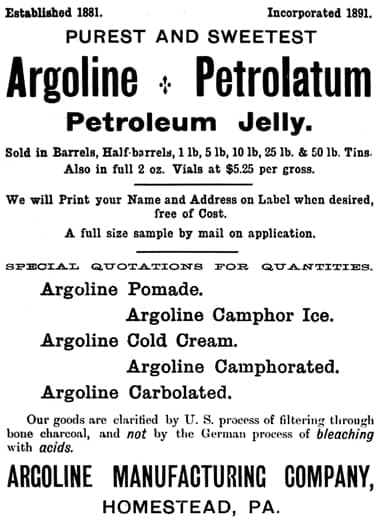

1891 Argoline Petroleum Jelly.

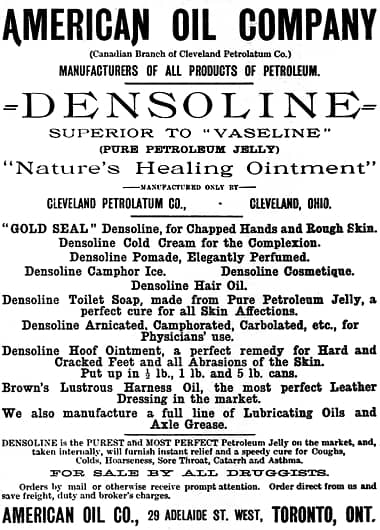

1891 American Oil Company Densoline.

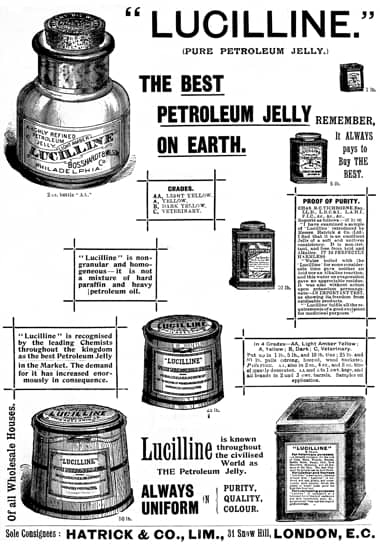

1895 Bosshardt & Wilson Lucilline Petroleum Jelly.

1911 Vasoline Petroleum Jelly products.

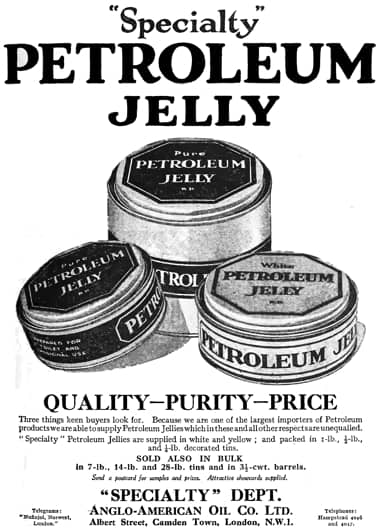

1924 Anglo-American Specialty Petroleum Jelly.

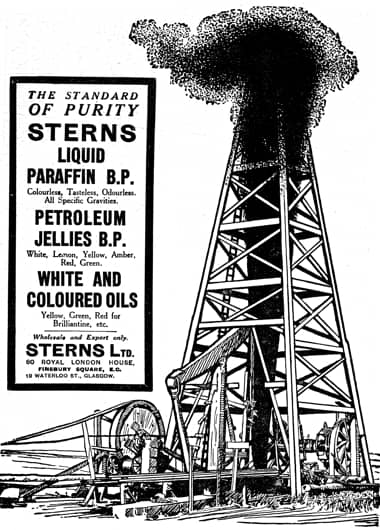

1928 Sterns Liquid Paraffin, Petroleum Jellies, and White and Coloured Oils.