Chesebrough Manufacturing Company

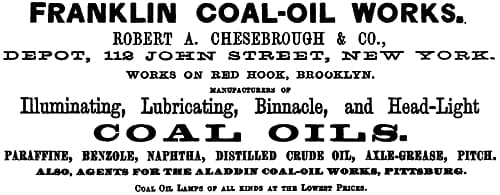

In 1858, Robert Chesebrough went into the coal-oil business using coal-oil he purchased from the Aladdin Oil Works in Allegheny, Pennsylvania. At a factory in Red Hook, Brooklyn, he produced a range of products from the coal-oil including lighting oil – also known as paraffin oil or kerosene – which he sold under his Luxor Oil brand from his depot at 112 John Street, New York.

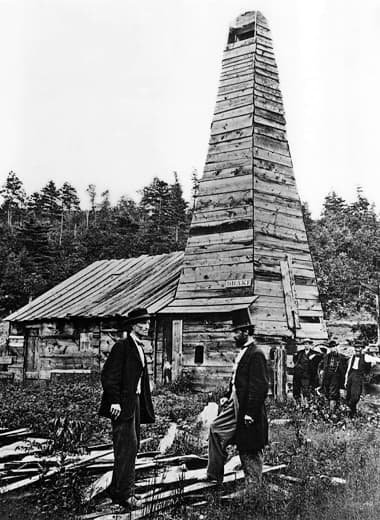

Above: 1860 Franklin Coal Oil Works.

In 1859, ‘Colonel’ Edwin Drake successfully drilled for oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania. Hearing news of the strike, Robert Chesebrough visited Titusville to see for himself what prospects were available. There, according to tradition, he came across ‘rod wax’ a refuse material obtained from the tubing and rods of pumping wells. It was from this material that Chesebrough eventually extracted what came to be known as Vaseline, a name he trademarked in 1872.

The process Chesebrough developed for extracting Vaseline started with a careful distillation of the source material using vacuum stills to remove the light oils followed by filtering the remaining mass through bone black.

The process by which “Vaseline” is made is the only known process of deodorizing petroleum without impairing its properties for medicinal, pharmaceutical, and toilet purposes.

… [I]n the manufacture of “Vaseline” no acids are used, the petroleum being simply concentrated by dry heat to a jelly, and repeatedly filtered through animal charcoal, substantially as white sugar is made, and is perfectly harmless.(Chesebrough brochure, 1886)

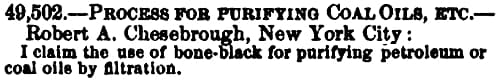

Chesebrough had been experimenting with bone black for some time. In 1860, he had tried to patent a method using bone black to purify petroleum or coal oil.

Above: 1860 Patent application for purifying petroleum or coal oils.

Perfecting the method to commercially extract Vaseline from rod wax took Chesebrough a decade to develop and was not accomplished until 1869. In 1870, he added facilities to manufacture Vaseline to his factory in Red Hook with Vaseline becoming available in 1871 (Chesebrough Manufacturing Company, 1885, p. 1).

Vaseline

Vaseline is a form of petroleum jelly. Chesebrough derived the name ‘Vaseline’ from a combination of ‘wasser’ (German for water) and ‘elaion’ (Greek for oil) – it was a ‘water-oil’. Like many other chemists of the time, Chesebrough would have believed that petroleum oil was formed by a chemical action between carbon and hydrogen in water. In the twentieth century, this idea lost ground to the Geological Theory but by then the word had stuck.

Vaseline was trademarked in Britain (1887), the United States (1878) and in a few other places such as Australia and New Zealand but similar applications failed in Germany, France, Spain, Latin America, Japan, China and elsewhere as authorities there considered that the name was too generic.

Sales

Chesebrough promoted Vaseline as a curative and soothing agent, as well as a base for ointments and salves. Wholesale and retail druggists were largely disinterested in it and sales were low until he began sending out employees with carts to hand out free samples to housewives and doctors – it is estimated that over half-a-million such samples were distributed by 1873 (Williamson, Andreano, Daum & Klose, 1959, p. 251). Chesebrough was the first company to distribute free samples on such a massive scale and others learnt from its success. The free samples were made possible in part by Vaseline’s low cost. The free distribution was later replaced by sample packs; sold at a nominal charge and sent postage free to customers who wrote in for it.

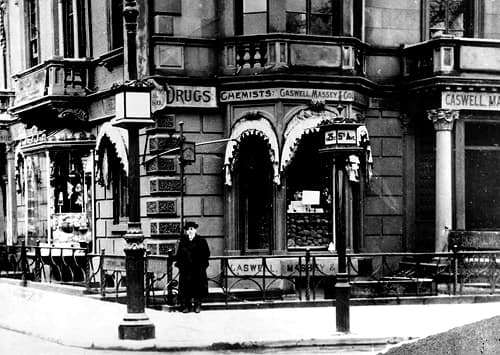

Two early commercial customers appear to have been the Edmond Fougera and Caswell-Massey drug stores.

Above: Caswell-Massey Drug Store on the corner of 25th Street and Fifth Avenue, New York.

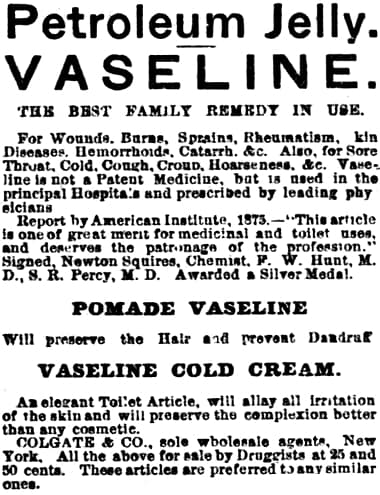

In 1873, an agreement was reached with Colgate & Company for it to distribute Vaseline nationwide in the United States. This arrangement continued on after Palmolive-Peet and Colgate merged to form Colgate-Palmolive-Peet in 1928 and lasted, almost uninterrupted, until Chesebrough merged with Pond’s in 1955.

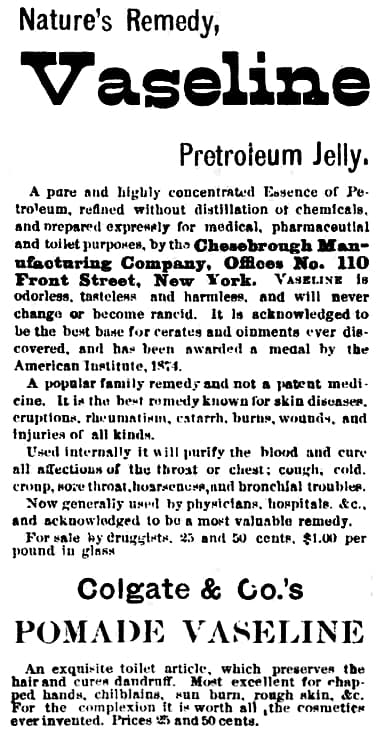

By 1874, reports of the product began to appear in New York newspapers.

A new product from petroleum called vaseline promises to be of considerable value in the arts, and to enter into very general use for medicinal, pharmaceutical and toilet purposes. It is a highly concentrate essence of petroleum refined, without distillation or chemicals, by a process discovered by Mr. Robert A. Chesebrough of this city. …

As an emollient, it is claimed to be superior to glycerine or to any substance yet discovered in softness and healing qualities, being admirably adapted to toilet purposes and for chapped hands and lips, sunburn, musketo [sic] bites, for use after shaving, and lip preparations for the hair, and keeping the head sweet and clean. For pharmaceutical use, vaseline bids fair to supply a want which has long been felt and never yet supplied, In the endless variety of ointments, cerates and embrocations which are in use, something has to be used as a base for their admixture, and hitherto animal or vegetable substances have of necessity been relied on, such as lard, suet, or olive oil. But all these, in time, decay and become rancid, thus impairing and destroying the value of the admixture, and necessitating constant fresh preparation, Vaseline never changes, but will preserve indefinitely the medicaments incorporated into it, and will add to, rather than detract from their value.(A New Petroleum Product (1874, February 27). New-York Daily Tribune, p. 2)

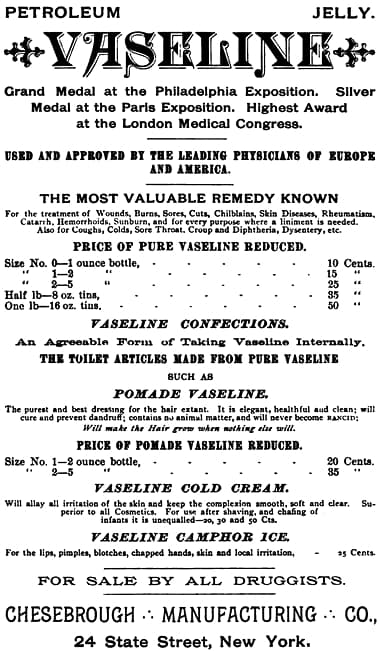

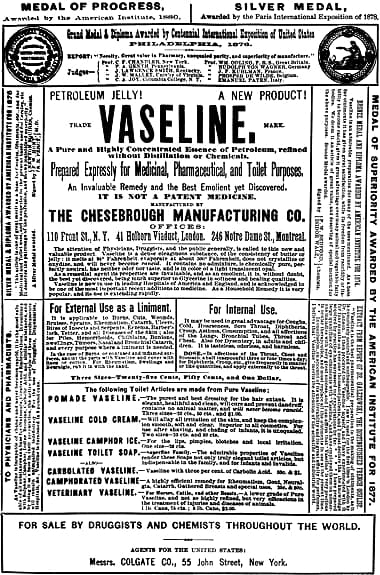

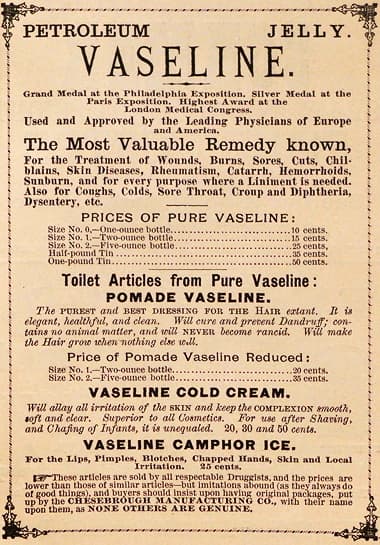

To help sales, Chesebrough also submitted Vaseline to a range of scientific and medical societies and displayed it at various national and international expositions. Awards for the product included Silver Medal American Institute (1875), Grand Medal Centennial Philadelphia Exposition (1876), Silver Medal Paris Exposition (1878), Medal of Progress American Exposition (1880), Silver Medal Atlanta Exposition (1881), and Highest Award International Medical Congress, London (1881).

In 1876, Vaseline got a major boost when it was endorsed by the London medical journal ‘The Lancet’. This led to an increased interest from physicians in the United States, Britain and Europe (AP&EOR, 1927), and marks the beginning of Vaseline’s establishment as a global household staple. Following its general acceptance by the medical profession, Chesebrough embarked on a general advertising campaign aimed at the public at large.

In 1874, the Chesebrough Manufacturing Company was founded with a capital of US$500,000 with its offices at 110 Front Street, New York. Manufacturing continued on in Brooklyn but the headquarters of the company shifted around New York largely due to Robert Chesebrough’s property investments which involved redeveloping the Battery Park area in New York. In 1881, the company moved from 110 Front Street to a building Chesebrough erected at 24 State Street, Battery Park but then moved again in 1899 to a new Chesebrough Building at 13-19 State Street.

Above: 1899 The Chesebrough Building (right-front) at 13-19 State Street, Battery Park.

Global expansion

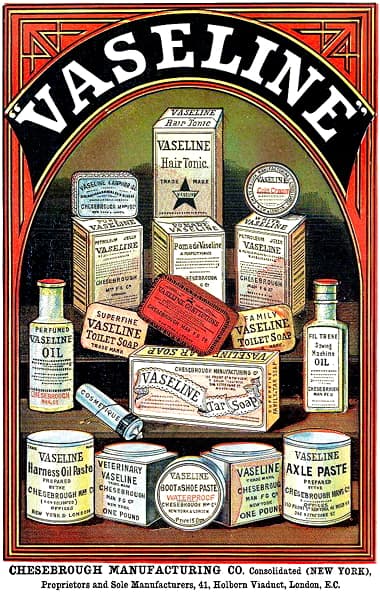

Chesebrough also expanded the company overseas, starting with Britain in 1875 selling its products through an agent. In 1877, the company opened a depot at 7 Snow Hill, London, managed by Robert Chesebrough’s brother, Colonel William Henry Chesebrough [1839-1905]. The London depot was moved to 41 Holborn Viaduct in 1880 before settling at 42 Holborn Viaduct in 1888. Depots were also established at 13 Avenue de L’Opera, Paris, France, 83 St. James Street, Montreal, Canada and agencies were established elsewhere around the world, reaching Australia by 1877. In 1880, all the various branches around the world were merged with the parent company to form the Chesebrough Manufacturing Company Consolidated.

Above: 1900 Delivery wagon in front of the Chesebrough Depot at 42 Holborn Viaduct, London.

The British branch of Chesebrough would remain at Holborn Viaduct until 1923 when it moved to Victoria Road, Willesden. The new facilities in Willesden included a finishing and packing plant. This was the second factory the company had built outside the United States, the first being established in Montreal, Canada in 1910.

Above: 1931 Chesebrough factory and offices in Victoria Road, Willesden.

Standard Oil

In 1881, Chesebrough became majority owned by the Standard Oil Trust established by John D. Rockefeller [1839-1937] and Henry M. Flagler [1830-1913] in 1870. The alliance was mutually advantageous. For the trust, Chesebrough was a lucrative outlet for a petroleum by-product. For Chesebrough, an alliance with Standard Oil gave them a reliable source of supply and enhanced protection from competing products that appeared on the market. Chesebrough would remain part of Standard Oil until the trust was broken up in 1911.

As business increased, Chesebrough enlarged its manufacturing facilities in Brooklyn to cope with the added demand. For example, it began building twenty-two brick and iron filter houses to increase production of Vaseline in 1885. However, it soon became clear that the company’s interests would be better served by moving to a new site and a search began for a suitable location.

In February, 1903, a tract of land – known locally as the ‘Kearny Farm’ – was bought in Perth, Amboy, New Jersey and construction commenced in April of that year using the George W. Mercer Construction Company, a local contractor. Chesebrough then moved production of Vaseline from Brooklyn to Perth, Amboy, completing the shift in 1904.

Above: 1953 Chesebrough plant in Perth, Amboy.

Products

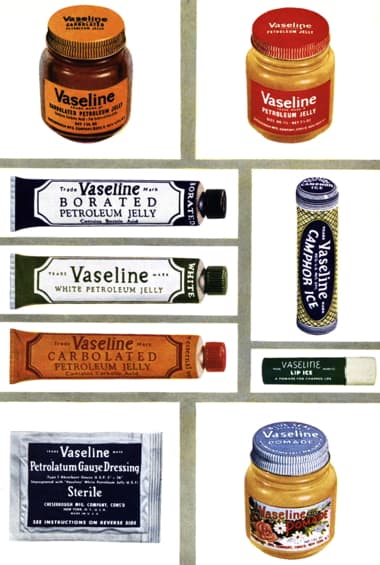

Robert Chesebrough found a wide variety of uses for his Vaseline. Part of the reason for this was that the manufacturing process for making Vaseline resulted in white, blonde, and red types, with varying degrees of purity. White, being the purest, was best suited for use for ’external applications of a delicate nature and for refined toilet purposes’, yellow for general use, while red, the least pure, was more appropriate for ordinary pharmaceutical ointments, veterinary uses and treating leather goods.

Vaseline is especially useful in carrying, stuffing, and oiling all kinds of leather. It is also a good lubricator, and may be used to great advantage on all kinds of machinery. The finest grade of vaseline is also adapted to use as a pomade for the hair, and will be found excellent for that purpose, one of its chief recommendations being that it does not oxidize. It is also an excellent substitute for glycerine-cream for chapped hands, &c., which it resembles closely in touch and somewhat in appearance.

(U.S. Patent No. 127,568, 1872)

See also: Petrolatum/Petroleum Jelly

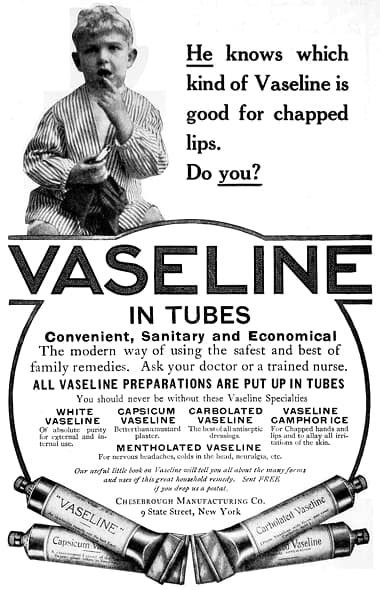

Chesebrough produced products in all of the categories mentioned in his 1872 patent, many of which came in convenient tubes by 1905.

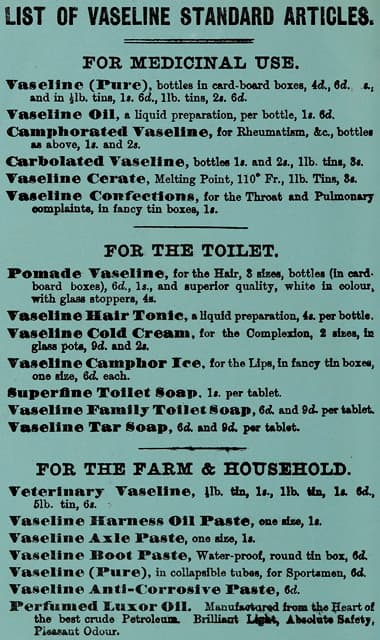

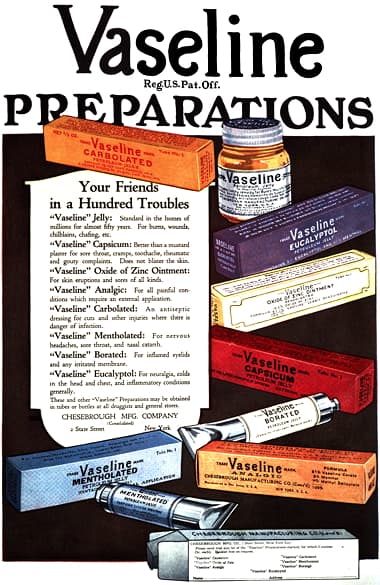

Medicinals

Medicinal products included Vaseline, White Vaseline, Vaseline Oil, Camphorated Vaseline (for Rheumatism), Carbolated Vaseline (containing carbolic acid), Vaseline Cerate, Vaseline Analgic, and Vaseline Confections (for throat and pulmonary complaints).

White Vaseline: “Colds and sore throats are easily helped by White Vaseline taken internally. Has no taste. Children take it more readily than other medicines.”

Capsicum Vaseline: “Better than a mustard plaster; easier to apply and does not blister the skin. Rub on at night for sore throat or cold in the chest.”

Carbolated Vaseline: “This perfect antiseptic dressing is the safest way of utilizing the cleansing and healing values of Carbolic Acid, with the soothing comfort of Vaseline.”

Mentholated Vaseline: “Relieves headache, neuralgia or any nerve pain. The menthol soothes the nerves while Vaseline conducts it quickly to the seat of trouble.”

Camphorated Vaseline: “Pure Vaseline with eight per cent. gum camphor. Highly efficient for rheumatism, gout, etc.

Vaseline Eucalyptol: “Snuffed into the nostrils, it protects the delicate membrane-with an antiseptic film no irritation. Its action is disinfecting, cleansing.”

Vaseline Analgic: “[C]ools neuralgic surfaces, quiets rheumatic pain, takes the ache out of headache and makes a bad tooth behave.”

Toiletries

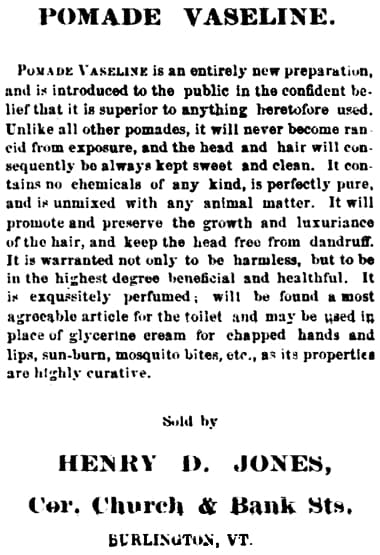

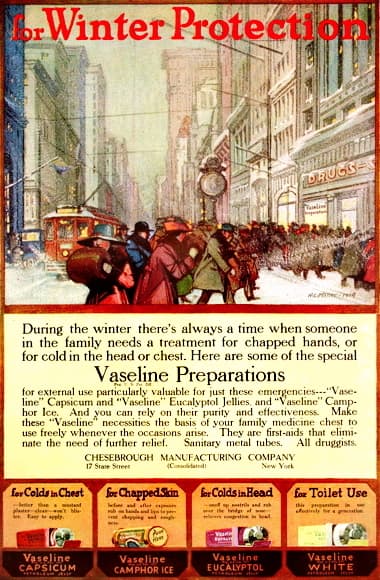

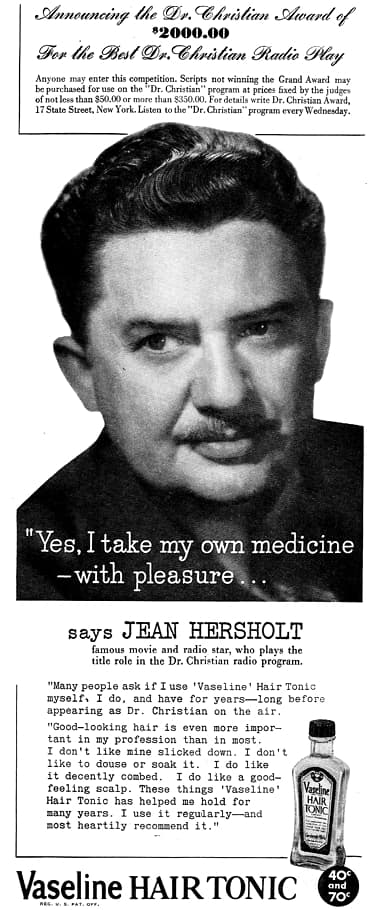

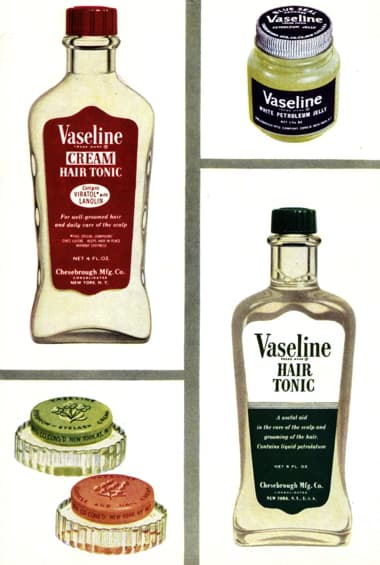

For toilet use there was Vaseline Camphor Ice, Pomade Vaseline (for hair), Vaseline Oil (perfumed for hair), Vaseline Hair Tonic, Vaseline Cold Cream, Vaseline Cosmetique and a variety of soaps including Superfine, Family and Tar.

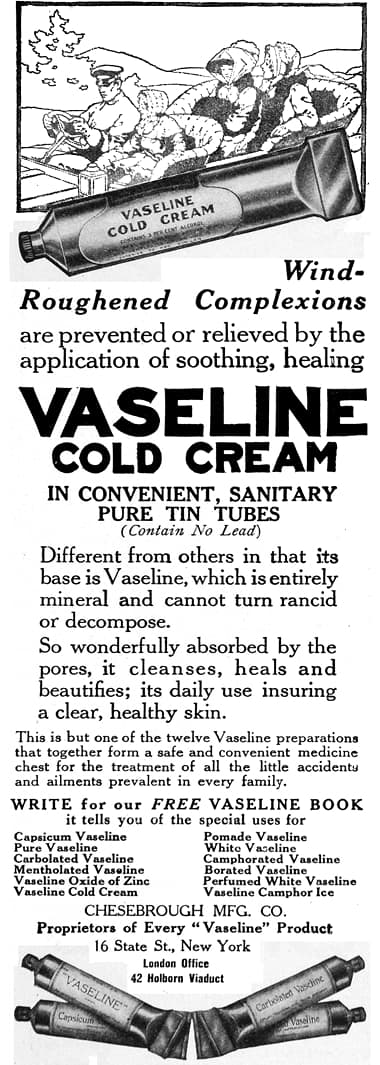

Vaseline Cold Cream: “Will allay all irritation of the skin and keep the complexion smooth, soft and clear. Superior to all Cosmetics. For use after Shaving, and Chafing of Infants, it is unequalled.”

Vaseline Camphor Ice: “Superior to anything in use for chapped hands and lips and to allay all irritation.”

Pomade Vaseline: “The purest and best dressing for the hair extant. It is elegant, healthful and clean. Will cure and prevent Dandruff; contains no animal matter, and will never become rancid. Will make Hair grow when nothing else will.”

Vaseline Hair Tonic: “[U]nlike any other prparation offered for the hair. It is a real hair fertiliser, and is to hair what sunlight is to plant life.”

Leaving aside the hair products, there are three items of particular interest to the story of cosmetics – Vaseline Cold Cream and Vaseline Cosmetique.

1. Vaseline Cold Cream was the first commercial skin-care product to be made using a refined petroleum ingredient. Its main advantages over traditional cold cream formulations were its lower cost and longer shelf life. It was widely copied and led to the incorporation of petrolatum into a wide variety of face creams and other cosmetics.

See also: Cold Creams

2. Vaseline Cosmetique was sold in a metal container with a removable stick which suggests it was used to temporarily cover grey hair. This would make sense considering that Chesebrough was already making a pomade and a hair tonic. If so, it would be a precursor for other petrolatum-based cosmetics used by women to darken their eyebrows and eyelashes. The Densoline Cleveland Petroleum Co. sold a similarly named product named ‘Densoline Cosmetique’ in large and small sticks wrapped in silver paper. This is consistent with it being a temporary hair colourant which, unlike water cosmetique, would not run at the first sign of perspiration.

See also: Water Cosmetique

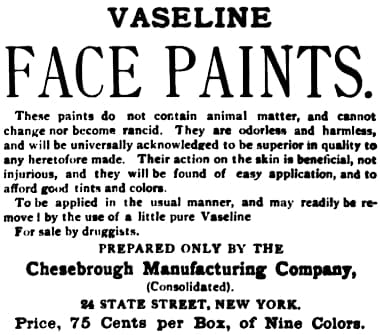

3. Vaseline Face Paints were introduced in 1888 and were, in all likelihood, greasepaint sticks. Whether they were sticks or a cream they were the first greasepaints to replace the usual lard, tallow or beef-suet with petrolatum.

See also: Greasepaint

Others

Chesebrough also sold ‘Filtrene’ (a sewing machine oil), Veterinary Vaseline, Vaseline Boot Paste, Vaseline Anti-Corrosive Paste, Vaseline Harness Paste and Vaseline Axle Paste, all of which could be used around the house or farm.

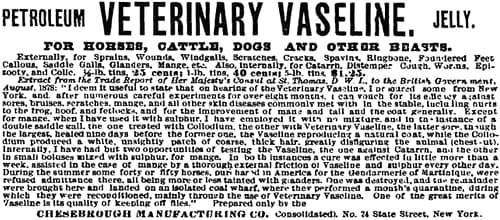

Above: 1886 Veterinary Vaseline.

Separation

In 1909, Robert Chesebrough retired and was succeeded by his nephew, Oswald deNormandie Cammann [1859-1944], who had previously held the position of vice president. Cammann was therefore the head of the company when Standard Oil was broken up and Chesebrough became an independent company.

Separation from Standard Oil, meant that Chesebrough lost its guaranteed supply of the raw materials and this led to the manufacture of Vaseline Petroleum Jelly being temporarily discontinued in 1920. The directors of the company appear to have been aware of the growing problem. In 1919, Chesebrough had raised additional funds by issuing 5,000 shares at US$100 a share. The directors also proposed to increase the powers of the company by allowing it to explore and drill for petroleum and other related products, produce and manufacture petroleum products, buy other companies and do business in other American states and in foreign countries. In 1920, Chesebrough used some of the capital it had raised to acquire a controlling interest in Duhring Development Company, Pennsylvania and in Clifton Oil & Gas, West Virginia thereby giving it assured access to the raw materials it need. Chesebrough maintained its interest in both Duhring and Clifton until 1948.

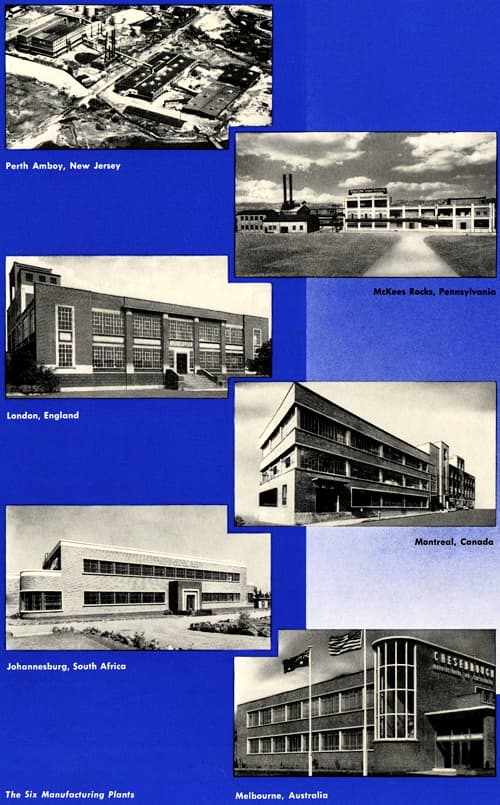

In 1921, Chesebrough issued another 5,000 shares at US$100 a share citing the need to increase expenditure on plant and manufacturing capacity, improve its marketing facilities and insure its product supply. Subsequently, in 1923, additional manufacturing capacity was opened in McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania. This helped the company service its growing customer base. As far as I can tell, all the Vaseline used around the world at the time was made in the United States with any manufacturing elsewhere being limited to finishing and packaging.

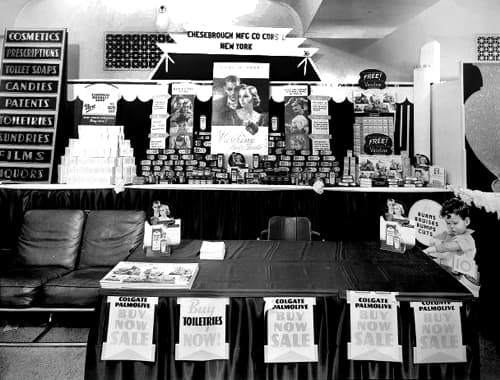

Above: 1937 Chesebrough display at the National Association of Retail Druggists Convention in St. Louis, Missouri.

The stockmarket crash of 1929 affected the company less than many others, Chesebrough maintaining its profitability and continuous record of dividend payments throughout the Great Depression.

Above: Vaseline delivery truck.

New products

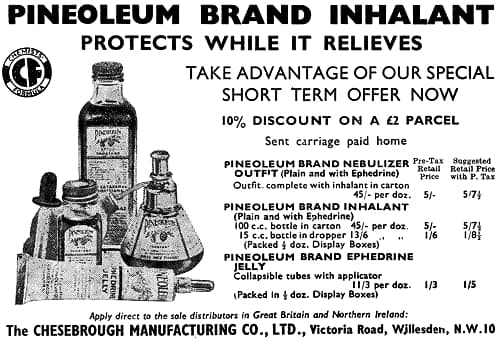

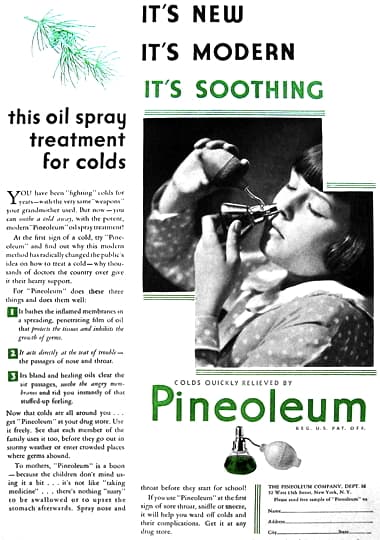

In 1929, Chesebrough purchased the Pineoleum Company, the makers of a nasal spray. Other than this there were few new products added in the interwar period, the only ones that I know of being Vaseline Lip Ice (1934) and Vaseline Soapless Shampoo.

Vaseline Lip Ice: “[F]or chapped, sore or cracked lips; cold and fever sores.” Shades: Lip Ice White and Lip Ice Rose.

Vaseline Soapless Shampoo “[T]horoughly cleanses the scalp of all scurf and dandruff—no soap scum left behind on the scalp.”

Chesebrough was aware of its lack of product development. In 1940, to address this, the company established a fellowship at the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was hoped that Mellon would help Chesebrough develop new products and development improvements in its manufacturing practices.

War

America did not enter the Second World War until the end of 1941 but, after 1939, Chesebrough’s business in most other countries was disrupted as foreign markets closed or became restricted.

Britain was Chesebrough’s most important foreign market at the time but restrictions on import licenses, lack of shipping space, introduced quotas, higher sale taxes and damage from air raids made it difficult to conduct business there. In 1940, these difficulties company directors decided to detach the business in Britain as separate subsidiary, the Chesebrough Manufacturing Company Ltd.

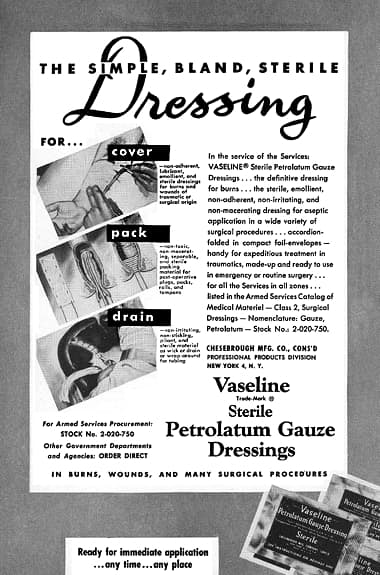

In the United States there were some positive developments. In 1942, at the request of the Surgeon General of the U.S. Army, the Mellon Institute developed a sterile dressing for battlefield and hospital use. Chesebrough was awarded a contract to produce the dressing and, in 1944, a new facility was built at the McKees Rocks plant to make and package it. Sales of the Sterile Petrolatum Gauze Dressing to the Army and Navy helped the company have its best ever domestic sales figures in 1944.

Above: 1954 Manufacturing Vaseline Sterile Petroleum Gauze Dressing.

Vaseline Sterile Petroleum Gauze Dressing: “[A]n absorbent gauze impregnated with ‘Vaseline’ White Petroleum Jelly.”

Post war

After the war, Chesebrough began to reorganise and modernise. Baybank Pharmaceutical – the renamed Pineoleum Company – was experiencing reduced demand for its products so the decision was taken to sell its assets and the company was dissolved in 1946.

Above: 1945 Pinoleum.

Confident that it no longer needed to control the production of its raw materials Chesebrough also sold off the assets of the Duhring Development and the Clifton Oil & Gas and then dissolved both companies in 1948.

Chesebrough also upgraded its manufacturing capacity. It retooled its American factories at Amboy and McKees Rocks and diversified its production capabilities, completing a new plant in Germiston, South Africa in 1949 and another in Melbourne, Australia in 1953.

Above: 1954 Chesebrough factories.

In 1954 Chesebrough celebrated the 75th anniversary of the incorporation of the company. Its products were sold around the world and sales were good but new product development continued to be a major weakness as it limited the possibility of growth. Most of its medical lines were being rapidly superseded by developments in the pharmaceutical industry and it had few opportunities to expand its consumer lines.

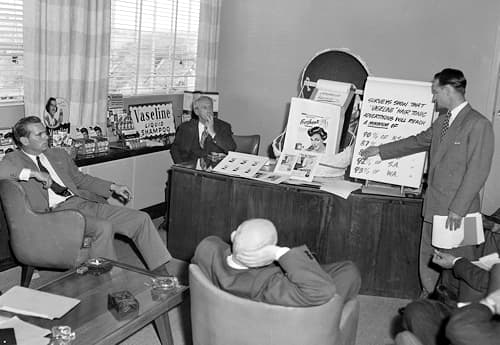

Above: 1953 Chesebrough sales meeting (Melbourne, Australia).

Merger

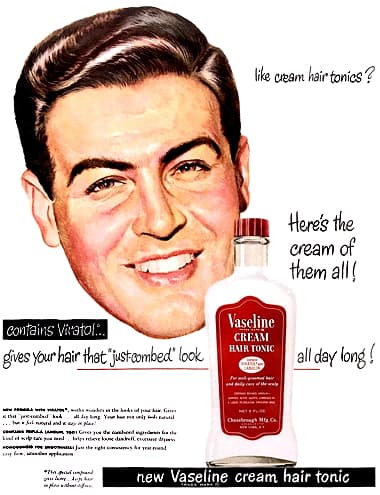

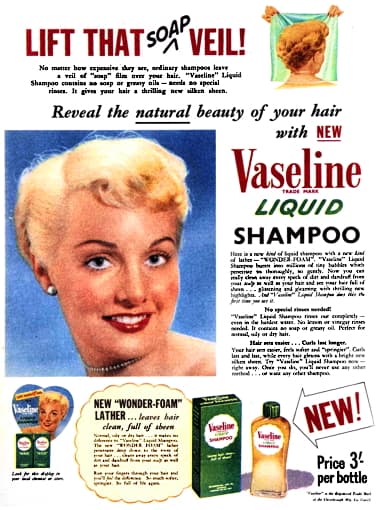

Chesebrough’s principle products in 1954 were Vaseline Petroleum Jelly, Hair Tonic, Cream Hair Tonic and Lip Ice. Although the Vaseline Cream Hair Tonic (1948) was doing well, other products introduced after the war – Vaseline Eyebrow-Eyelash Cream, and Cuticle and Nail Cream (1948) and Vaseline Liquid Shampoo (1950) – were less successful.

Vaseline Cream Hair Tonic: “[C]ontains Viratol (with lanolin), an exclusive compound which imparts a ‘just-combed’ look; keeps your hair neat without stiffness.”

Vaseline Eyebrow-Eyelash Cream: “for highlighting and grooming brows and lashes; gives soft luminous effect to the eyelids without coloring.”

Vaseline Cuticle and Nail Cream: “softens, helps control cuticle and prevent roughness and hangnails.”

Vaseline Liquid Shampoo: “[W]ill make your hair look brighter, smarter, more manageable than every before.”

Increased competition in the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries during the 1950s combined with the need to engage in expensive television advertising placed further pressure on the Vaseline product range. These and other factors persuaded the Chesebrough board to enter into a merger with the Pond’s Extract Company in 1955. Combining with Pond’s would allow the two companies to rationalise their production, administration, sales and advertising costs, improve their research activities and broaden the appeal of their products. Fortunately, the new entity, Chesebrough-Pond’s, proved to be very successful.

See also: Pond’s Extract Company and Chesebrough-Pond’s

Timeline

| 1858 | Robert Chesebrough starts in the coal-oil business. |

| 1870 | Machinery to manufacture Vaseline installed in the factory in Red Hook, Brooklyn. |

| 1871 | New Products: Vaseline Petroleum Jelly. |

| 1872 | Process for making petroleum jelly patented. |

| 1873 | Colgate & Co. agrees to distribute Vaseline. |

| 1874 | Chesebrough Manufacturing Company founded. |

| 1876 | Endorsement of Vaseline by the ‘The Lancet’. New Products: Vaseline Cold Cream. |

| 1877 | Chesebrough opens a London depot at 7 Snow Hill. Vaseline trademarked in Britain. |

| 1878 | Vaseline trademarked in US. |

| 1880 | Chesebrough foreign companies amalgamate with the United States to form Chesebrough Manufacturing Company, Consolidated. London depot moves to 41 Holborn Viaduct. |

| 1881 | Standard Oil Company acquires majority interest in Chesebrough. Chesebrough Building erected at 24 State Street, Battery Park, New York. |

| 1888 | Blue Seal label first used. Trademark filed in 1892. London depot now listed at 42 Holborn Viaduct. New Products: Vaseline Face Paints. |

| 1899 | New Chesebrough Building erected at 13-19 State Street, Battery Park. |

| 1904 | Manufacturing moved from Brooklyn to larger plant in Perth Amboy, New Jersey. |

| 1908 | Vaseline jar screw thread tops replaced corked tops. |

| 1909 | Chesebrough retires and is succeeded by Oswald Cammann. |

| 1910 | Canadian plant opened in Montreal. |

| 1911 | Standard Oil broken up and Chesebrough Manufacturing becomes an independent entity. |

| 1920 | Duhring Development Company and Clifton Oil & Gas Company bought. |

| 1923 | New American factory built at McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania. British business moves to Victoria Road, Willesden. |

| 1928 | Chesebrough begins radio advertising. |

| 1929 | The Pineoleum Company acquired. |

| 1934 | New Products: Vaseline Lip Ice. |

| 1940 | British company incorporated as a separate entity (Chesebrough Manufacturing Company Ltd.). |

| 1944 | Chesebrough begins production of Vaseline Sterile Gauze Dressing. |

| 1946 | The Pineoleum Company renamed Baybank Pharmaceuticals, Inc. |

| 1947 | Branch established in India. |

| 1948 | Duhring Development Company and Clifton Oil & Gas Company liquidated. New Products: Vaseline Cream Hair Tonic; Vaseline Eyebrow-Eyelash Cream; and Vaseline Cuticle and Nail Cream. |

| 1949 | Baybank Pharmaceuticals, Inc. dissolved. Factory established in Germiston, South Africa. |

| 1950 | New Products: Vaseline Liquid Shampoo. |

| 1953 | Factory established in Melbourne, Australia. |

| 1954 | New research laboratory opened at the Perth, Amboy plant. |

| 1955 | Chesebrough merges with Pond’s to form Chesebrough-Pond’s. |

Updated: 21st April 2020

Sources

The American perfumer & essential oil review. (1927). New York: Robbins Perfumer Co.

Chesebrough Manufacturing Company. (1884). Petroleum: Its origin, uses and future development. A highly interesting sketch. London: Author.

Chesebrough Manufacturing Company. (1885). Vaseline: Its history, uses and therapeutic value. Also, as a base in official (U.S.P.) and other formulas. Interesting tp physicians, pharmacists, veterinary surgeons, and others. New York: Author.

Fougera, E. (1884). American Druggist. 13, April, 62.

Hall, H. (Ed.). (1895). America’s successful men of affairs. An encyclopedia of contemporaneous biography (Vol. I). New York: New York Tribune.

Tower, W. S. (1909). The story of oil. New York: Appleton and Company.

Williamson, H. F., & Daum, A. R. (1959). The American petroleum industry: The age of illumination 1859-1899. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

Williamson, H. F., Andreano, R. L., Daum, A. R., & Klose, G. C. (1963). The American petroleum industry: The age of energy 1899-1959. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.

Robert Augustus Chesebrough [1837-1933].

c.1860 Edwin Drake [1819-1880] (right) in front of the engine house and derrick in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

1873 Pomade Vaseline.

1875 Vaseline Petroleum Jelly.

1876 Pomade Vaseline and Vaseline Cold Cream.

1877 Vaseline products.

1880 Vaseline products.

1884 Vaseline Standard Articles.

1886 Chesebrough Manufacturing Company (London).

1886 Pomade Vaseline, Vaseline cold Cream and Vaseline Camphor Ice.

1888 Vaseline Face Paints. These first appeared around 1888 but seem to have disappeared within a few years.

1891 Vaseline Blue Label Trade Card.

1908 Vaseline in tubes.

1910 Vaseline Cold Cream.

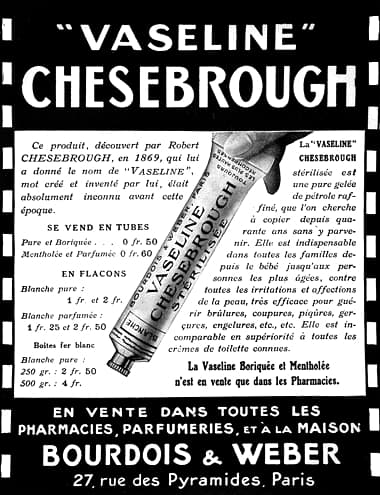

1910 Vaseline (Paris).

1911 Chesebrough Building at 13-19 State Street, Battery Park built in 1899 from white cream bricks made by the Powhatan Clay Manufacturing Company. Architects Charles W. Clinton [1838-1910] and William H. Russell [1856-1907]. It was sold to the real estate broker, Joseph P. Day [1874-1944] in 1919.

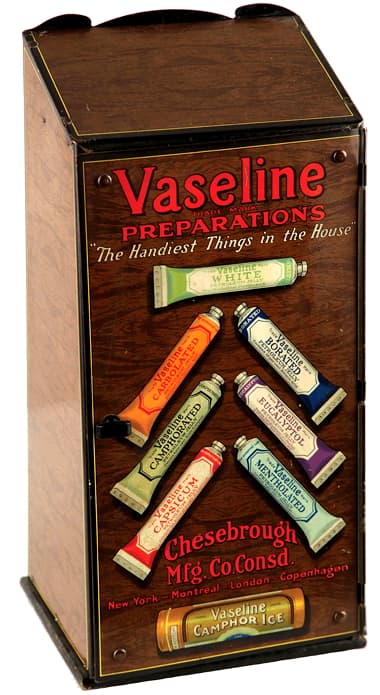

Vaseline Display Case.

1918 Vaseline preparations in tubes.

1919 Vaseline Mentholated Petroleum Jelly.

1920 Vaseline Capsicum, Camphor Ice, Eucalyptol, and White.

1921 Vaseline Hair Tonic.

1931 Pineoleum.

1934 Vaseline Petroleum Jelly.

Vaseline Lip Ice (Germany). This appears to be the Rose version.

1942 Vaseline Hair Tonic promoted by Jean Hersholt a.k.a Jean Pierre Carl Buron [1886-1956]. He played Dr. Christian in the radio play of the same name that was sponsored by Chesebrough starting in 1937.

1948 Vaseline Cream Hair Tonic.

1949 Vaseline Cream Hair Tonic, White Petroleum Jelly, Eyebrow-Eyelash Cream, Cuticle and Nail Cream, and Hair Tonic.

1949 Vaseline Carbolated Petroleum Jelly (jar), Petroleum Jelly, Borated Petroleum Jelly, White Petroleum Jelly, Carbolated Petroleum Jelly Tube), Camphor Ice, Lip Ice, Sterile Petrolatum Gauze Dressing, and Pomade.

1950 Vaseline Sterile Petrolatum Gauze Dressing.

1950 Vaseline Liquid Shampoo (Australia).