Royal Jelly

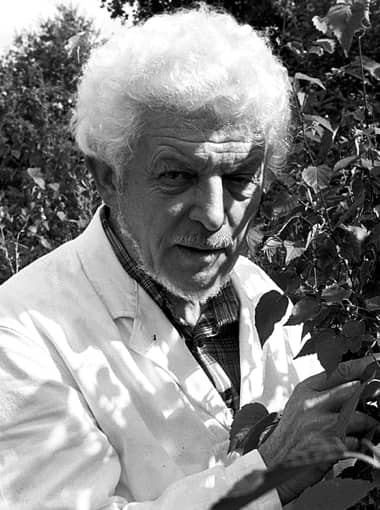

Serious cosmetic interest in royal jelly began in France in 1950 through the work done by the Station Apicole by the station director Rémy Chauvin and his associates. Apicole’s research was picked up by Orlane and, in 1953, the company introduced its first product made with royal jelly, Crème a la Gelée Royale.

Orlane’s use of royal jelly was copied by other French firms and American firms with French connections. Alexandra de Markoff, a subsidiary of Charles of the Ritz, was the first company to release a royal jelly cosmetic in the United States – Elixir de Markoff (1954). Others, from brands such as Harriet Hubbard Ayer, Marie Earle, Richard Hudnut, Lesquendieu (Tussy), and Germaine Monteil, soon followed.

Not everyone got involved in the fad. Helena Rubinstein apparently consulted Sir Edmund Hillary [1919-2008] – the noted mountain climber and apiarist – when she visited New Zealand, got a negative report and decided against the idea, remarking that “women are not bees. Bees are insects and women are human beings” (Perutz, 1970, p. 62). However, this did not stop Rubinstein from adding it to her Beauty for Life Capsules, each containing 30 milligrams of royal jelly along with a range of vitamins.

Brood food

Originally thought to be pre-digested food, royal jelly – also known as bee milk, brood food, or pap – was found to be the product of the salivary glands of nurse bees. It is fed to worker and drone larvae for the first few days of their life before their diet is changed to pollen and honey. Queen bees on the other hand are fed royal jelly, and only royal jelly, for their entire life, both as larvae and as adults. Worker bees are sterile and only live for a few months while queen bees are fertile and live for several years. These reproductive and life-extending properties of royal jelly led to speculations about possible effects on humans.

Scientific interest in the regenerative properties of royal jelly goes back earlier than 1950, to the 1920s at least, a decade noted for the work of Serge Voronoff [1866-1951] and Eugen Steinach [1861-1944] into the rejuvenating effects of hormones. For example, in 1929, Frederick G. Banting [1891-1941] – one of the discoverers of insulin – and his associates at the University of Toronto, Canada, began a study of the chemistry of royal jelly to determine the ingredient that was responsible for its stimulating effects.

See also: Rubinstein and the Rejuvenationists

The suggestion that royal jelly might have rejuvenating or anti-ageing properties led to a number of questionable medicinal and cosmetic claims. European literature of the time suggested that it prevented wrinkles, rejuvenated skin, cured acne and helped male pattern baldness (deNavarre, 1962, p. 163). Claims that it contained estrogens, was radioactive, or that it might be a good source of vitamin E, fuelled speculation that it had miraculous rejuvenating powers. As chemists analysed its ingredients cosmetic companies used this information to add to its mystique.

THE QUEEN BEE

The great thing about every Queen Bee is her diet—(Royal Jelly). Without it she’d be just like any other bee in the hive: with it she is a prodigiously young and active Queen Bee through at least 30 bee generations!

This Royal Jelly is one of the phenomena of the world. No wonder its human application has been an irresistible medical pursuit for centuries.

The Riddle-of-the-Hive is a Classic Mystery. Or was. Until in 1894 Dr. Leonard Bordas started unraveling it. Its composition was finally synthesized revealing valuable vitamins, proteins and minerals and Royal Jelly became increasingly respected in European medical practice.

It was this same Dr. Bordas at 92, distinguished Professor of Science and Medicines, who writing recently to Lilly Daché, President of Marie Earle, referred to Royal Jelly as an “Agent de reactivation des processes vitaux.” This official nod plus the information that at last Royal Jelly could be captured sent Miss Lilly Daché winging to France-to confer with the Royal Jelly scientists.

More than convinced she has had her most benign cream strongly fortified with Royal Jelly fresh from the French apiaries. Her cream, MARIE EARLE’S QUEEN BEE CREAM is now available … packed and sealed in France … necessarily in limited quantities, necessarily $15 per ounce.

About it, Miss Daché says, “What can it do for any woman’s skin? I have just seen French complexions that were so beautiful and so amazingly young for their years. If we are all going to live so long now, we must live young longer. No? And I believe this Royal Jelly will do it. The pity is that every woman can’t have it. You see, only a Bee can make it. The Riddle now is not only which among the bees will have it, but which of us?”(Marie Earle advertisement, 1955)

Royalty

It may just be a coincidence, but a factor that may have contributed to the royal jelly fad was the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953. The coronation created a strong public interest in royalty and the young Queen Elizabeth in particular, only recently surpassed by that expressed for Diana, Princess of Wales. Many people bought their first television set to watch the 1953 coronation. Sales of cosmetics containing royal jelly began before the death of George IV in 1952 but may have been helped after 1953 by the fact that the product was so easily associated with ‘queens’ and ‘royalty’.

Composition

The composition of royal jelly varies slightly from location to location but chemical analysis indicated that it consisted of water, proteins, sugars, lipids, vitamins and minerals, all of which made it a complete food, at least for bees. This is not surprising, given that it is the only substance queen bees eat for their entire life. Royal jelly did not have high levels of vitamin E but it did contain material that would help the bee larvae fight infection in the warm, moist environment they sit in at the bottom of a honeycomb cell.

Chemically, royal jelly contains 66.05% moisture, 12.34% protein, 5.46% lipids, 12.49% reducing substance, 0.82% minerals and 2.84% of unidentifiable elements. Within this complex mixture are found natural hormones, enzymes, biocatalysts, and abundance of B vitamins—including thiamine, riboflavin, pyridoxine, niacin, pantothenic acid, biotin, instol and folic acid—vitamins A, E, C and acetylcholine, along with 20 different amino acids, fatty acids, sugars, sterols, phosphorous compounds (including DNA and RNA) and a gelatinous precursor of collagen. Additionally royal jelly contains gamma globulin, and infection-fighting an immuno-stimulating factor, and decanoic acid, which exhibits strong antibiotic activity.

(Schlossman, 2002, p. 463)

Royalactin

The chemical responsible for the development of a queen has recently been identified and named ‘royalactin’. Royalactin is a protein that affects the growth of bees and is not an estrogen-like substance that affects fertility as earlier thought. This makes it less likely to have any effect on humans when used as a food supplement or in cosmetics; it would be broken down by the digestive system when eaten and is unlikely to penetrate the skin if used in a cream.

Cosmetic use

Royal jelly is a thick, off-white paste. The lack of a distinct colour makes it easy to incorporate into cosmetics as it does not need to be decolourised like pollen. Over the years it has been added to a large number of cosmetics including face creams, eye creams, hand lotions, lipsticks, cake and liquid foundations, shampoos, and nail enamels and is still used in cosmetics today.

The amount included in cosmetics is generally minimal. Alexandra de Markoff’s Elixir de Markoff facial cream contained 100 milligrams of dried royal jelly in each 30 gram jar which meant that it made up less than 0.5% of the mixture. Maison deNavarre states that between 100 and 200 milligrams of royal jelly were used per ounce of product in the United States. This concentration is stronger than that used in Europe where between 50 to 1000 mg per 100 grams of product was the norm (deNavarre, 1962). Although the price of royal jelly fluctuated, the additional cost of adding it to a cosmetic in the 1950s is unlikely to have exceeded 20 cents per jar. Considering that creams were priced at up to US$15 each, there was plenty of money to be made selling it in the 1950s and 1960s.

Cosmetic claims

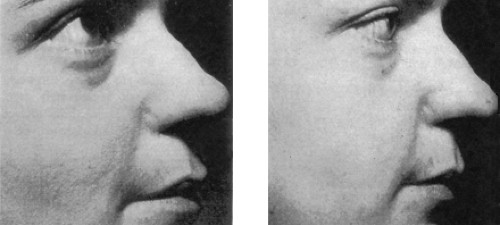

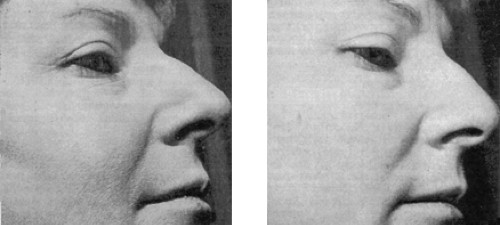

In the late 1950s, the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the American Federal Trade Commission (FTC) investigated the use of royal jelly in drugs, foodstuffs and cosmetics in the United States. They found that most of the claims made for royal jelly were unwarranted and that much of the European scientific evidence used to back them was untraceable or suspect. For example, research into the cosmetic use of royal jelly by Dr. Paolo Rovesti [1902-1983] reported a number of positive results for creams and face-packs using royal jelly, queen bee larvae or a combination of royal jelly and larvae. The pictures below are before and after treatments with royal jelly alone.

Left: ‘Mixed’ type of skin before treatment. Right: The same skin after 5 treatments with royal jelly. “Definite eudermic action is noted with minimum number of enlarged pores and small wrinkles. Smooth and homogeneous surface”.

Left: ‘Greasy’ type of skin before treatment. Right: The same skin after 5 treatments with royal jelly. “The pores are very much less enlarged and the surface of the skin is much smoother and more homogeneous”.

Left: ‘Dry’ type of skin before treatment. Right: The same skin after 5 treatments with royal jelly. “The wrinkles around the mouth have almost disappeared, the skin is much more hydrated and toned up, more elastic, smooth and homogeneous”.

It is difficult to see major skin improvements in the photographs above, particularly given that the lighting used in the before and after treatments differs. When we also note that the creams and face-packs Rovesti used contained 3% royal jelly – a much higher concentration than that used in commercial face creams – and that he did not add a similar quantity of material to his controls, we may be justified in concluding that any skin improvements may simply have been due to hydration and not to some special ingredient. This would also explain why his cream with mashed bee embryos in honey produced similar results.

On the plus side, unless the person is allergic to it – deaths from ingestion of royal jelly have been reported – royal jelly is usually harmless when eaten or applied to the skin.

Current practice

There are still some adherents of royal jelly today (e.g. Burt’s Bees) but by the middle of the 1960s the widespread practice of using it in cosmetics was largely over in the United States. The same was not true in Europe or Asia where it continues to have a following (e.g., Lancôme, Orlane, and Shishedo). Both places have long traditions of using honeybee products including honey, pollen, propolis, and beeswax.

Given that the amount used in cosmetics is low and that cosmetic claims for it are suspect, what is royal jelly good for? Personally, I would agree with deNavarre that royal jelly is really good for only one thing – it is good for bees!

See also: Pollen Extracts

Forst Posted: 26th June 2011

Last Update: 30th June 2022

Sources

deNavarre, M. G. (1962). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd. ed., Vol II). Orlando: Continental Press.

Perutz, K. (1970). Beyond the looking glass. Life in the beauty culture. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Rovesti, P. (1960). New cosmetological research into royal jelly and bee embryo. Soaps, Perfumes and Cosmetics. June, 605-608.

Schlossman, M. L. (Ed.). (2002). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (4th ed., Vol III). Carol Stream, Il: Allured Publishing Corporation.

Rémy Chauvin [1913-2009] was the director of the Station de Recherches Apicoles (Beekeeping Research Station) in Bures-sur-Yvette, France from 1948 to 1964. This photograph was taken in 1978.

Queen bee larvae floating on royal jelly.

1953 Orlane Crème a la Gelée Royale.

1957 Alexandra de Markoff Elixir containing 100 milligrams of royal jelly per ounce of cream.

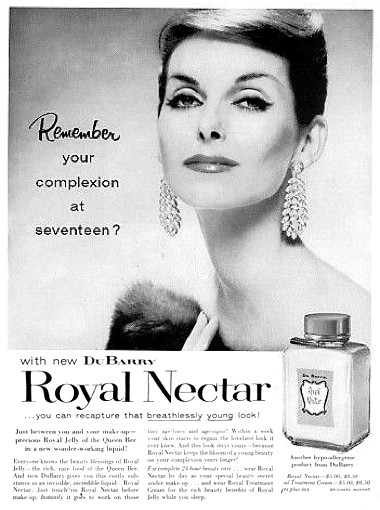

1957 Du Barry Royal Nectar containing royal jelly.

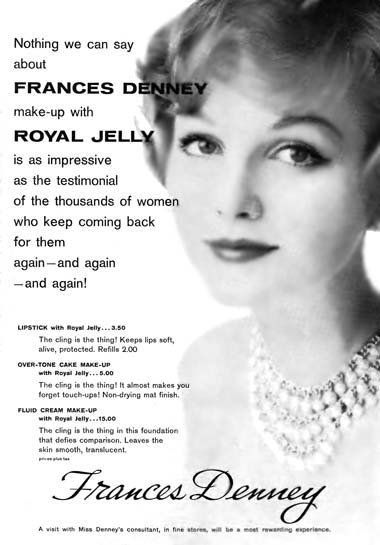

1958 Frances Denney Royal Jelly Make-up. As well as make-up, Frances Denney included it in a wide range of creams including her Viva Cream, Eye Cream, Neck and Contour Blend, Invisible Beauty Strap, Creme Supreme, and Multi-layer Moisturizer.

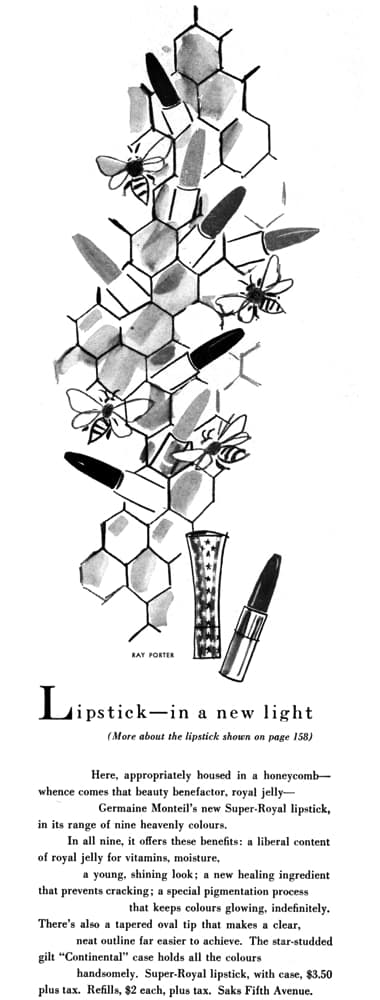

1958 Germaine Monteil Super-Royal Lipstick.

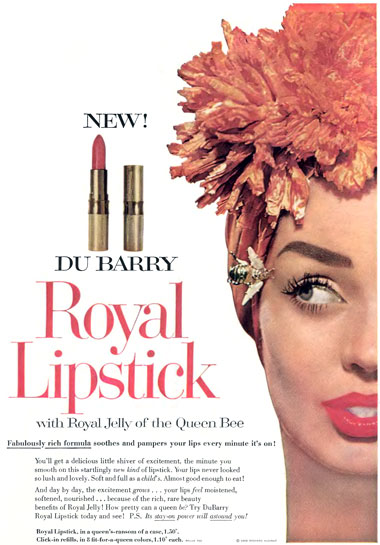

1958 Du Barry Royal Lipstick. Other Du Barry products containing royal jelly included Royal Velvet Liquid Make-up, Cloudsilk Face Powder, Royal Nectar Lotion, Royal Treatment Cream, and Royal Balm Hand Lotion.

1958 Germaine Monteil Super-Royal Cream with royal jelly. Note the emphasis on fertility and longevity. Germaine Monteil also produced lipsticks and other cosmetics containing royal jelly.

1959 Gelée Royale as a dietary supplement from the Centre de Diététique, Paris.

1964 Orlane products with royal jelly.