Pollen Extracts

Pollen is produced as part of the reproductive cycle of flowering plants. It is spread by wind and/or animals, with insects being major pollinators. Once the pollen reaches its destination, it begins to grow, producing a pollen tube which gradually extends down to reach and fertilise the female part of the flower.

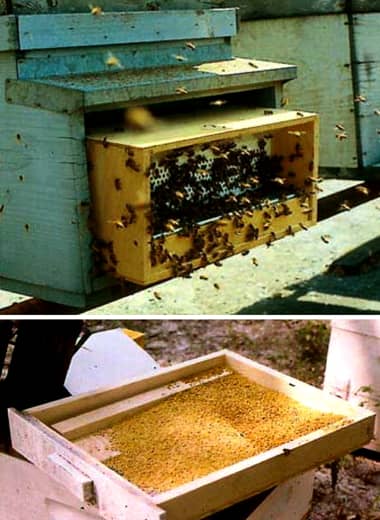

Collecting pollen

Commercial quantities of pollen can be collected from honey bees by placing a pollen trap at the entrance of a bee hive. The trap forces the bees to pass through small holes that dislodges the pollen from the legs of the bees as they enter the hive. The pollen than falls into a tray and is later collected by the apiarist. Although individual bees are careful to collect pollen from only one source, if the hive is working a number of different flower species, the tray will be filled with a range of pollens each with their own colour.

Composition

Flower pollen grains have a tough, outer wall that protects the inner genetic material from physical injury, desiccation and solar radiation. Like all living tissue this inner cellular material is made up of a range of biological and other compounds. A series of studies of pollen determined its composition to be as follows:

Pollen contains from 10 to 35% protein … composed of eighteen different amino acids; reducing and nonreducing sugars; 1 to 20% fats; starch up to 20%; nucleic acids; trace elements—K, Mg, Ca, Fe, Si, P, and S; oligo-elements Mn, Ti, Cu; vitamins A, B, C, D, and E; hormones; enzymes; and an antibiotic.

(deNavarre, 1962, p. 158)

Along with vitamins – which were still enjoying an elevated status in skin creams in the 1950s – the hormones and enzymes found in pollen were of interest to French investigators. Cosmetic researchers felt that the ‘biocatalysts’ and ‘biostimulants’ found in pollen could be useful additions to anti-wrinkle, nourishing and moisturising skin creams. Pollen grows and plays a part in reproduction so the thought was that it might contain vegetative versions of the ‘skin rejuvenating’ substances supposedly found in embryo extracts and plant versions of the ‘skin youthifiers’ believed to be produced by animal hormones.

See also: Vitamin Creams, Embryo Extracts and Hormone Creams, Oils and Serums

Pollen in cosmetics

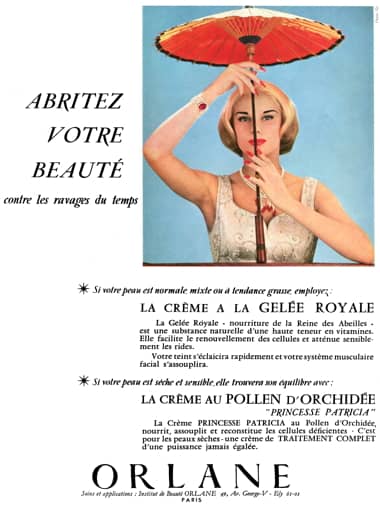

Cosmetic interest in pollen followed the introduction of royal jelly – known in France as gelée royale – and, like royal jelly, its adoption started in France in the 1950s. However, its use in cosmetics never reached the levels achieved by royal jelly.

See also: Royal Jelly

If pollen grains were used in their raw state the exterior coat of the pollen could trigger an allergic reactions producing symptoms commonly associated with ‘hay fever’. The high colour of many pollens also created compounding difficulties, requiring the use of decolourising chemicals such as diethylene glycol monomethyl ether.

Above: Pollen collected by bees from a range of flower sources showing its high colour. The colour variation is due to different flavonoids and/or carotenoids present in the pollen.

In view of these problems, cosmetic chemists concentrated on producing pollen extracts rather than using the whole pollen grains. A range of solvents were used to create lipid-soluble and water-soluble extracts which were then used separately or combined together in cosmetics. In a French patent, Helena Rubinstein included a very simply recipe for a skin-cream using a lipid-soluble pollen extract, here translated:

Night Cream

g. Lanolin 50 Almond Oil 100 Ozokerite 30 Oily extract of pollen 20 Water 50 Preservative q.s. (French patent: FR1054555, 1954)

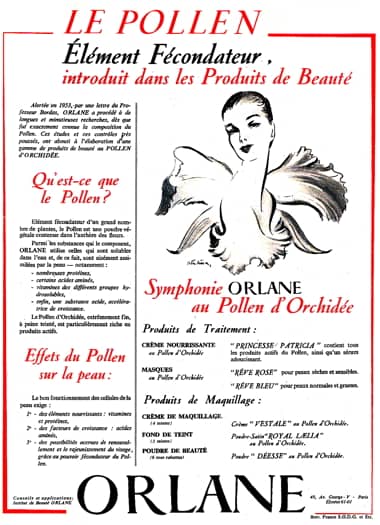

Orlane

The main promotor of pollen-based cosmetics in the 1950s was Orlane. Founded in 1947, Orlane had already introduced Crème Astrale with vitamins, Crème Intégrale with chicken embryo extract and Crème à la Gelée Royale containing royal jelly, so was already known for creams with biological additives. The company said they got the idea of using pollen from Professor Jean Bordas, Director of the Station of Agronomy and Plant Pathology in Avignon, France.

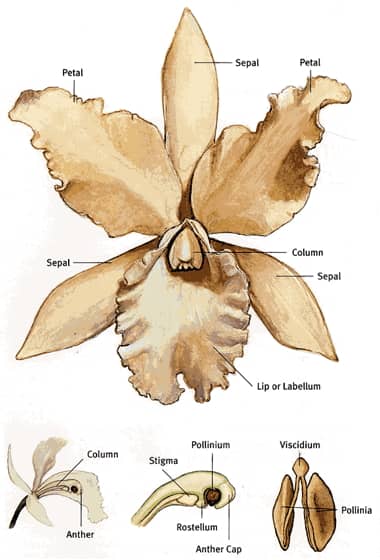

Rather than selecting pollen collected from French bee hives – which was easy to source – Orlane said that it used orchid pollen in its cosmetics. Orchid pollen is not collected by bees nor was orchid pollen grown commercially in France at the time. Orlane’s reasoning was that, unlike most pollens, orchids produced a clear, colourless extract which was richer in active ingredients. However, they offered no evidence to support these claims. It is also worth noting that both French patents taken out by the company (FR1116942: 1956; and FR1121630: 1956) do not mention orchids and include decolourisation treatments.

Exactly which orchids Orlane used to source its pollen is difficult to determine. The company suggested that it used Brassocattleya orchids (hybrids of the Brassavola and Cattleya genera) but the images it used in its advertising were from the genus Cattleya which has more spectacular flowers. In either case, the pollen from these flowers is not loose and granular but rather is packed into a waxy mass called a pollinarium that is not collected by bees for food.

Above: Orchid pollinarium.

To ensure pollination the orchids trick insects into mating with the flower so that the pollinarium can be stuck on the insect to be retrieved by another orchid flower when the insect attempts to mate with it. The link between the orchid and insect is strong with many orchid species only pollinated by a single insect species.

Above: Insect with pollinarium attached.

The reproductive arrangements used by orchids meant that collecting pollen from them had to be done by hand. Orlane used a horticultural company based in Kalimpong, West Bengal, India – still noted today for its orchid flower market – to do the collection. After being hand-collected the pollen was sent by air to the Orlane laboratories in Clichy for treatment. Exactly what orchid extracts Orlane used in its skin-creams is unknown to me but advertisements put out by the company only mention those that are water-soluble. Patents registered by the company suggest that these water-soluble extracts may have been produced simply by soaking the pollen in water. The amount of pollen extract used is also unknown but Orlane patents suggest that this might have been as little as 0.5% by weight. Company advertisements also make mention of proteins so pollen powder may have been used in some cosmetics – such as the face powders – despite the possibility of an allergic reaction.

Orlane cosmetics that contained orchid pollen extract included: Princess Patricia, a skin cream; Réve Rose and Réve Blue, masks for dry and normal/oily skin respectively; Crème Vestal, a cream make-up; and Poudre-Satin Royal Laelia and Poudre Deéese, face powders. Orlane credited orchid pollen with providing the skin with nutrients from vitamins and proteins as well as growth factors from amino acids. In addition, Orlane suggested that the ‘fertilising power of pollen’ would help with skin renewal, a clear reference to the ‘biocatalysts’ and ‘biostimulants’ mentioned earlier.

Like most other biologicals in vogue during the 1950s – such as embryo extracts, royal jelly and placental extracts – cosmetic interest in pollen declined through the 1960s but was not entirely forgotten and it turned up occasionally in cosmetics and beauty treatments right through until the present day. Like royal jelly, it is also widely promoted as a nutritional supplement.

One recent development of interest is the distinction now made between ‘bee pollen’ (pollen collected by bees) and ‘flower pollen’ (pollen harvested directly from flowers). According to this distinction, as the orchid pollen used by Orlane was collected by hand, Orlane orchid pollen cosmetics may therefore be the earliest commercial ‘flower pollen’ products ever produced.

Updated: 8th December 2016

Sources

deNavarre, M. G. (1962). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd ed., Vols. II). Orlando, FL: Continental Press.

Florent, R. (1956). Les extraits de pollen. La Parfumerie Modern. 53, Sept-Oct, 52-55.

Jellinek, J. S. (1970). Formulation and function of cosmetics (G. L. Fenton, Trans.). New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Horak, D. (2004). Orchids and their pollinators. Retrieved August 24, 2016, from http://www.bbg.org/gardening/article/

orchids_and_their_pollinators

Krell, R. (1996) Value-added products from beekeeping. FAO agricultural services bulletin No. 124. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Luzuy, H. (1956). Caractères bio-chimiques du pollen et de la gelée royale. La Parfumerie Modern. 53, Sept-Oct, 41-51.

Schlossman, M. L. (Ed.). (2002). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (4th ed., Vol III). Carol Stream, Il: Allured Publishing Corporation.

Wells, F. V., & Lubowe, I. I. (1964). Cosmetics and the skin. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation.

Honey bee foraging for pollen and nectar. Bees compress the pollen they collect into a pollen basket on their hind legs.

Pollen trap (top) and removed tray with captured pollen (bottom). the pollen is very homogeneous suggesting it was collected from a single flower type.

1956 Orlane Pollen d’Orchidée.

An orchid flower from the genus Cattelya, the type Orlane used in its advertising.

The structure of a Cattelya orchid showing the position of the pollinarium (Horak, 2004).

1957 Orlane Masques with pollen d'orchidée.

1958 Orlane Princess Patricia crème au pollen.

1962 Funel Crème “Royal Iris” with pollen. Lilies were probably selected as the flowers produce pollen in abundance.

1986 Livia Sylva treatments with Romanian bee pollen.