Massage, Wrinkles and Double Chins

By the end of the nineteenth century massage was widely practiced in Europe, Britain and the United States. The skill level of practitioners varied wildly, running from individuals who did little more than rub the skin, to trained masseurs, masseuses and members of the medical profession.

Medically, massage was generally combined with exercise and manipulations to form what is often called mechanotherapy. It was also used in conjunction with other physical therapies popular at the time like hydrotherapy (water), electrotherapy (electricity), phototherapy (light) and thermotherapy (heat). The massage system commonly used was ‘classic’ massage – often called ‘Swedish’ massage – developed by Dr. Johann Georg Mezger. From it, we get the well-known techniques of effleurage (stroking), petrissage (lifting and kneading), friction (pressure), tapotement (tapping) and vibration (vibrating).

Massage soon found its way from the medical to the domestic sphere. The Physical Culture movement was well developed by 1900 and the health and beauty benefits of gymnastics and massage were promoted in books, magazines and newspapers. Individuals could also select from a growing range of mechanical or electrical devices to bring the benefits of vibrational massage into the privacy of their home.

Given all of these factors it is easy to see why massage was adopted by the rising number of beauty salons for use in treatments for the body, hands, feet and face, particularly when you realise that most professional massage was then, as now, carried out by women – either by nurses or specialist masseuses.

What [a facial] massage does

Exercises the muscles gently and makes the tissues firmer;

Brings about an improvement in the friction of the skin, thus causing an improvement in coloring and general appearance;

Increases nutrition by attracting blood to the surface;

Destroys effete matter and stimulates lymph channels in their work of carrying away this waste;

Stimulates the nerves to greater activity;

Increases blood and lymph supply by effect on nerves;

Eradicates superficial lines and imparts a more youthful expression to the face.(Lloyd, 1915, pp. 132-133)

Massage and muscles

Observational studies and clinical trials, conducted by the medical profession and others in the nineteenth century, credited massage with numerous benefits including revitalising muscles. Physical therapy doctrine of the period went so far as to suggest that massage was second only to exercise in strengthening muscle tissue. As well as the direct effect of massage on the muscles and the nerves that supplied them, the improved circulation produced by massage was thought to benefit muscles by elevating the amount of nutrients reaching them and aiding the removal of harmful wastes through the lymphatic system.

Although the muscles receive a certain blood supply, this supply is comparatively small except during activity; consequently, it may be said that “the muscles are well fed only when exercising.” When the muscle is inactive, the blood goes around it rather than through it; but the moment activity of the muscle begins, there is a great increase in its blood supply, even before any acceleration in heart activity has occurred.

Massage may serve to a considerable extent as a substitute for exercise by increasing the blood supply of a muscle, just as exercise may be considered a sort of massage, through the pressing and rubbing of the muscles against each other. When properly administered, the manipulations of massage act upon the muscles in such a way as to produce a suction or pumping effect pressing onward the contents of the veins and lymph channels, and thus creating a vacuum to be filled by a fresh supply of fluid derived from the capillaries and the tissues.(Kellogg, 1895, pp. 23-24)

Although the medical benefits of the treatments were of primary concern, there were suggestions that massage could also be used for aesthetic results.

Facial massage may be made useful in removing wrinkles, which as often indicate unhealthy tissues as advancing age or a wearisome existence. Wrinkles are best relieved by making traction upon the skin in a direction at right angles with the wrinkles, the wrinkled part being thoroughly manipulated to restore the natural flexibility of the skin, which has been lost.

(Kellogg, 1895, p. 141)

Facial massage and wrinkles

The idea that massage could ‘exercise’ muscles made it attractive to the growing beauty industry which used it in a range of treatments including facials. If sagging skin was due to a weakening of the facial muscles, then massage could be used to build up the underlying muscle tissue and firm the skin, thereby improving the facial contour and reducing lines and wrinkles.

If the arm or leg were to present the appearance of shrinking and withering apparent in the face of almost every woman over fifty, all physicians of all schools would agree the patient required massage, friction, gymnastics, and perhaps electricity to strengthen the weakened muscles. There have, indeed, been cures of seemingly hopeless paralysis, by massage, continuously, systematically, and scientifically given.

If a shrunken arm may be restored to symmetry and perfect contour, why not a shrunken cheek? Obviously one result is as logical as the other.(Ayer, 1902, p. 173)

As wrinkles appear in specific areas of the face, beauty procedures were developed to treat each of the problem areas. Given that massage was to work on the underlying tissue, therapists were required to learn the position and direction of most of the major muscles of the face as well as the associated blood vessels, lymphatic ducts and nerves.

Purpose: to stimulate orbicularis oculi and corrugator muscles; to stimulate temporal nerve, and erase fine lines at the corner of the eye (“crow’s feet”).

Place both hands flat on frontalis with all fingers at the median line. Using the heaviest possible stroking movement, slide hands to the temples; rotate at the temples, repeat light circular friction of 7, four counts, and press on the infratrochlear.(Marinello, 1932, p. 302)

Massage was believed by many to be able to build up fatty tissue as well as muscle. Loss of subcutaneous fat was regarded as another important cause of wrinkles in older women so beauty experts frequently added it to the list of benefits gained from a facial massage.

[G]enerally the skin of the face, from greater exposure, presents signs of age long before that of the rest of the body. Such ageing is premature, and is due to causes acting locally. This is our justification for considering massage of the face and neck apart from general massage.

Signs of age appearing in the skin—wrinkles, flabbiness and sagging—are due mainly to four factors—sluggish circulation, loss of skin elasticity, loss of subcutaneous fat, and a disturbance in muscle tonus (a condition resulting from repeated use of the muscles). All of these conditions respond to massage.(Modern Beauty, 1930)

Better-funded salons used trained masseuses to conduct massage treatments but later on, a knowledge of massage techniques became essential for all ‘treatment girls’. In-house treatment routines were developed and therapists were taught the various procedures, firstly through the salon they worked in, but later through specialist training schools as well. This process increased the separation between the therapeutic massage used in medicine and massage used in Beauty Culture. When the medical profession lost interest in massage after the Second World War, beauty salons maintained it and they became one of the places where it was most practiced until the field was revived in the 1970s as part of a growing interest in alternative medicine.

Although massage became a staple salon treatment, not everyone was convinced about the relationship between sagging muscles and wrinkles or the effectiveness of massage in treating these conditions. For example, the makers of Princess Pat cosmetics considered that massage would make these conditions worse:

It is not in the least true that “sagging muscles” cause any alleged ills . . . not wrinkles . . . not crows feet . . . not the annoying “pad” under the chin . . . not “scrawny neck.” Muscle structure has nothing whatsoever to do with these conditions.

The real truth is that massage aggravates all such conditions. Wrinkles, folds, sagging . . . all are caused by loosening of the skin . . . by wasting away of the cushioning tissue between the skin and the muscle structure. Massage definitely hastens looseness of the skin . . . assists in breaking down firmness . . . makes wrinkles worse.(Princess Pat, 1930, p. 16)

See also: Princess Pat

Patters and Straps

Some salon-based beauty firms were also skeptical that facial massage was the best thing for wrinkles. They worried that it would stretch the skin and, as the stretched skin sagged, cause wrinkles to be formed rather than removed. These beauty culturists, including Eleanor Adair and Elizabeth Arden, used other methods, such as vigorously patting or tapping the face with the fingers or a patter, in conjunction with chin and forehead straps.

Instead of steaming the skin, which robs it of its natural oils, or the vigorous massaging, which stretches the tissues and often produces flabbiness, the skin is gently patted and strapped, increasing the blood circulation and training the flabby muscles into their proper place.

(Adair advertisement, 1913)

See also: Straps, Bandages and Tapes and Patters.

Facial gymnastics

A second approach capitalised on the idea that if massage was second best to exercise, then facial exercises would be a better way to reduce wrinkles. Although the idea was more popular in the general press than in salons, numerous facial gymnastic routines were put forward as a way to prevent and reduce wrinkles. Some beauty experts had a bet each way and suggested follow-up facial exercises to complement salon or home massage treatments.

See also: Facial Gymnastics.

Muscle Strapping

For others the problem was the type of massage being used. If the massage treatment was too superficial then there was a risk of stretching the skin without any improvements in muscle strength so what was needed was a deeper massage that worked on ‘exercising’ the muscles beneath the skin.

There are several systems of facial massage now in vogue, but the great disadvantage in some of them is the fact that, the manipulation being too superficial, the skin is apt to become loose and wrinkled. In the establishment set on foot, and personally managed by Mrs. Pomeroy at 29 Bond Street, this point has been carefully studied, however, and all the work is done by masseuses who have been specially trained for the purpose, and therefore understand how to knead the muscles that lie below the surface. This manipulation of the face tends to do away with wrinkles. The Pomeroy system of facial treatment, being based upon physiological and hygienic principles throughout, recommends itself to every woman whose complexion is defective.

(Browning, 1898, pp. 220-221)

Through the early part of the twentieth century this deeper facial massage gained a considerable vogue where it was known by a number of names including muscle stropping, muscle lifting, muscle toning and muscle strapping. Normally only offered to older patrons as an extra in a facial, it was a heavier, more forceful massage that used stronger massage movements such as vibration and tapotement.

Massage, jowls and double chins

As well as being able to build up and firm underlying tissue, massage was also credited with the ability to break it down.

Massage is a methodical manipulation of the skin for the promotion and preservation of its functions. It is a peculiar feature of massage that it will both reduce and develop tissues according to the way the various movements are applied. For instance, hard rubbing breaks up many of the minute cells of which the tissues are composed, thus causing the parts to waste, while moderate rubbing, by simply stimulating the circulation and rousing vital action in cell building, will cause these parts to grow. This should be borne in mind when manipulating the tissues.

(Daggett & Ramsdell, 1911, p. 5)

So, as well as being used to treat flabby skin and wrinkles, massage was also used to remove the fatty deposits associated with jowls and double chins; a major problem for older and/or overweight clients. It could therefore be used on both fat and thin faces; on wrinkles and double chins.

The difference between muscle strapping and general face massage lies primarily in the movements which are of a special character, more extended in duration and areas covered, and designed to produce a more vigorous effect on the deeper tissues and muscles.

The operator must acquire skill and rhythm. Vibratory massage is both soothing and stimulating, whereas the strapping movement is highly stimulating, bringing up the blood supply, feeding the sluggish tissues and carrying away waste matter. A great deal off corrective work can be done with this treatment; building up drooping and flabby tissue, creppy neck and hollow cheeks; reducing fatty deposits on back, etc.(Banford Academy, 1938, p. 93)

Beauty salons did not employ facial massage – general or muscle strapping – in isolation. It was combined with skin-care products – such as skin foods and muscle oils – that built-up muscle tissue and subcutaneous fat to reduce wrinkles or dissolved unwanted fat from areas where the facial contour needed improving; physical restraints like chin and forehead straps; and/or electrical treatments.

The type of massage used and whether it was accompanied by an astringent, fat-dissolving cream, muscle oil and/or skin food were important differentiations. In salons where it was believed that forceful, vibratory pressure could drive out fat from the face, the therapist would need to be careful where massage was applied to avoid adversely affecting facial contours.

See also: Skin Foods, Muscle Oils and Skin Tonics, Astringents and Toners

Electrical machinery

Generating vibrations and other forceful massage movements is quite taxing, so many therapists took another idea from physical therapy and began using vibrational machinery.

Vibration, effected by mechanical means, may be given almost as gently, almost as carefully, as by the well trained human hand, or it may be so carelessly and recklessly applied as to so seriously injure the patient.

Its efficiency lies in the fact that the individual space treated in regional massage is of a small area and that the movement—a gentle or a medium-strong concussion of circular nature, helps more rapidly than by hand to restore the relaxed tissue to normal tone by increasing blood supply to the part, and by causing passive movement of lazy muscles or those that have undergone fatty degeneration.

Furthermore, the massage thus applied is more even, more regular, than that given by hand, and is less tiresome to the operator, who may be called upon to treat such a number of cases in a single day, as would, if treated with honest thoroughness, be likely to tire out a practitioner.(Woodbury, 1911, pp. 282-283)

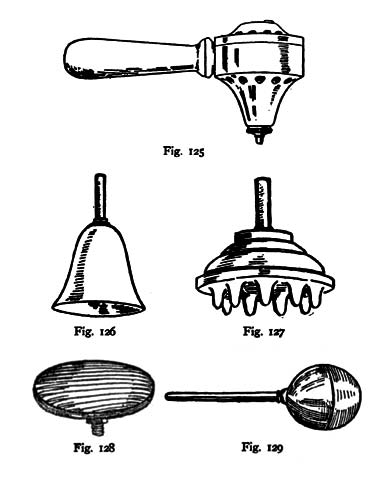

The machines used in facial routines were generally small, hand-held mechanical or electrical devices. Soft rubber cones were used if the treatment was to build up muscle but hard heads were substituted when fat deposits were to be reduced. These devices were widely available for sale and many were bought for home beauty treatments.

Massage and weight reduction

Logically, if massage could be used to remove fat from the face then it could also be used in a general weight loss program. This could be done by hand or by machine. Mechanotherapy had come to this conclusion in the nineteenth century and practitioners like Gustave Zander [1835-1920] constructed large vibratory machines that were later used in weight reduction. Larger beauty salons soon became equipped with machinery designed to massage away fat. Clients could also buy these machines and companies that made them advertised them for home use. It is said that Elizabeth Arden sold one to Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering [1893-1946], a well-known over-eater.

Change in emphasis

As the twentieth century progressed, making the client feel relaxed and free from stress and worry became an important part of a facial treatment. This was quite different to earlier times where relaxation was viewed as a necessary precursor to a facial not an end result.

In order to secure the very best results from the treatment it is necessary that your patron be taught to relax and keep absolutely quiet, in this way receiving all the good you desire her to procure.

(Lloyd, 1923, p. 185)

Using massage in a facial to relax the client required a softening of many of the massage movements of the past – which were applied more forcefully and with more speed than is currently practiced – and of course ruled out using an electrical vibrator on the face at all. Although still regarded by the beauty industry as an anti-ageing treatment, the focus of any salon massage today is as much on the mind of the client as it is on their face and body.

Updated: 25th October 2018

Sources

Ayer, H. H. (1902). Harriet Hubbard Ayer’s book of health and beauty. New York: King-Richardson.

Banford Academy of Hair and Beauty Culture. (1938). Theory and practice of scientific facial culture and muscle strapping. A textbook for the profession (Vol. 2). New York: Beauty Laboratories, Inc.

Browning, H. E. (1898). Beauty culture. London: Hutchinson & Co.

Calvert, R. H. (2002). The history of massage: An illustrated survey from around the world. Rochester, Vermont: Healing Arts Press.

Daggett & Ramsdell. (1911). Daggett & Ramsdell’s perfect cold cream [Booklet]. Philadelphia, PA: Wolf & Co.

Joslen, S. (1937). The way to beauty. A complete guide to loveliness. New York: Pitman Publishing Corporation.

Kellogg, J. H. (1895). The art of massage: Its physiological effects and therapeutic applications. Battle Creek, Michigan: Modern Medicine Publishing Company.

Lloyd, E. (1915). The Marinello text book (2nd ed.). Chicago: Marinello Company.

Princess Pat. (c.1930). This exquisite beauty [Booklet]. Chicago, IL: Author.

Smith, A., & Rockwood, R. (1935) Modern beauty culture. New York: Prentice-Hall.

The science of beautistry. Official textbook approved for use in all the national schools of cosmeticians affiliated with Marinello. (1932) New York: The National School of Cosmeticians, Inc.

Woodbury, W. A. (1911). Beauty culture. A practical handbook on the care of the person designed for both professional and private use. New York: G. W. Dillingham Company.

Dr. Johann Georg Mezger [1831-1901], Dutch physician and founder of classic massage.

Pehr Henrik Ling [1766-1839]. Ling pioneered the teaching of physical education in Sweden and is often mistakenly credited as the father of Swedish massage.

1902 Face massage (Ayer).

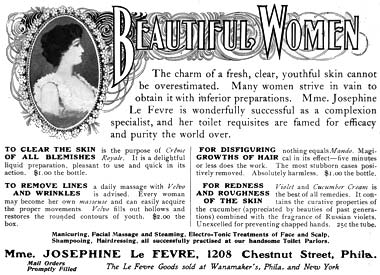

1902 Josephine Le Fevre. Remove lines and wrinkles with Velvo cream. “Every woman may become her own masseuse and can easily acquire the proper movements”.

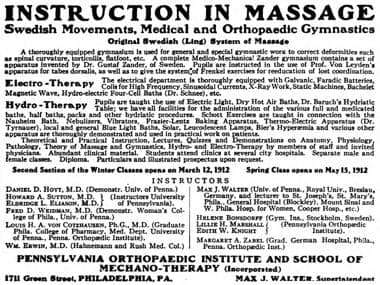

1912 Advertisement for training in the Original Swedish (Ling) System of Massage.

1923 Ego Wrinkle Remover. The Vivaudou Company recognised the role of facial movements in wrinkle formation. “When you laugh or cry or express any emotion, your facial muscles draw the skin into folds. As the underskin becomes dry, these lines become fixed, just as an iron presses folds into cloth”.

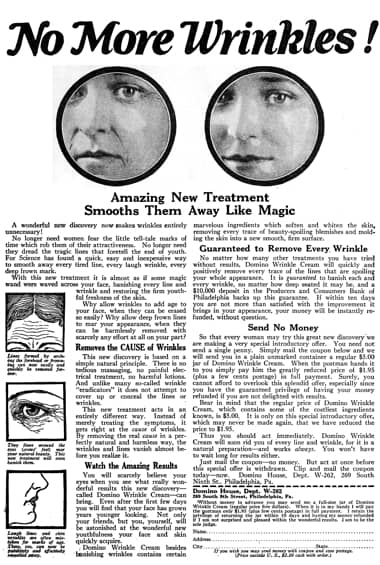

1923 Domino Wrinkle Cream. Many companies used skin-care creams in conjunction with massage but for others the cream was all that was needed.

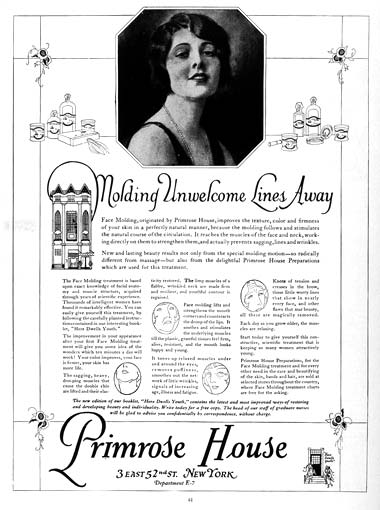

1924 Primrose House Face Moulding used a combination of massage, assorted preparations and chinstraps to remove double chins, wrinkles and other signs of ageing.

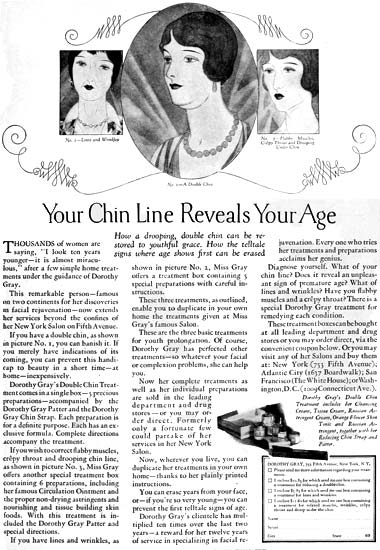

1926 Dorothy Gray. “Your chin line reveals your age”.

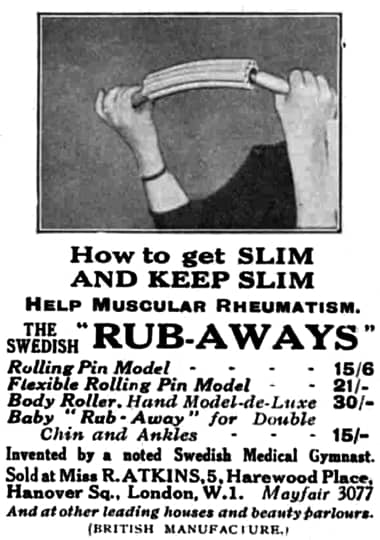

1928 Swedish Rub-Away.

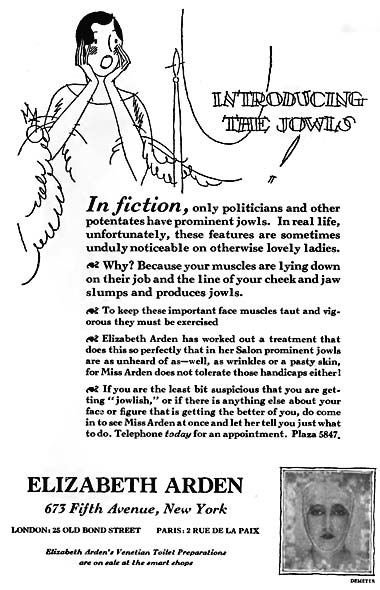

1928 Elizabeth Arden and the problem of jowls.

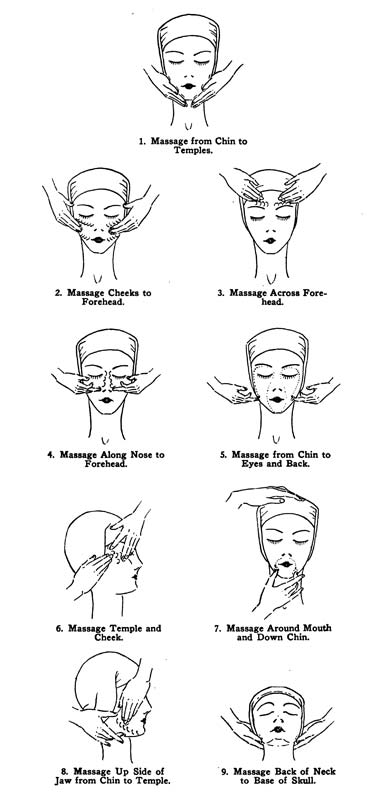

1935 A relatively simple facial massage routine (Smith & Rockwood). Massage movements were generally upward in direction, against gravity or across wrinkle lines.

1938 Muscle strapping movements (Banford). As well as the tapotement shown here, vibration was also commonly used.

1937 Kneading a double chin. “Kneading massage movements are good and can safely be performed by the amateur. Just press the thumb and forefinger alternatively into the flesh under the chin, keeping the thumb and finger close together“ (Joslen, 1937, p. 76).

Woman giving herself a face massage at home.

Hand-held vibratory massager with changeable attachments including soft heads for muscle stimulation and hard heads for fat reduction

1911 Drawings of the vibrator shown above with soft heads (Figs 126, 127) for muscle stimulation and hard heads (Figs 128, 129) for fat reduction.

Weight reduction treatments became very lucrative in the 1920s and 1930s and have remained so to the present day. The use of these machines, and others like it, is based on the belief that massage could tone muscles and reduce fat.