Skin Foods

As the skin ages it thins and wrinkles. To some early observers this was the result of a decline in subcutaneous fat which caused the skin to fall into folds. Early beauty books suggested that fat or oil applied to the skin would penetrate down into the tissues and replace the fat that was lost. ‘Feeding’ the skin in this way would make it younger looking and less wrinkled. This attractive idea is the basis of a group of cosmetics known as ‘skin foods’; also known as ‘tissue builders’, ‘tissue tonics’, ‘flesh foods’, ‘tissue creams’ and ‘nourishing creams’.

The object of a skin food is to prevent wrinkles which mar the smoothness and beauty of ever so nice a complexion. Mme. Qui Vive calls them “unnecessary evils—anyway until one gets to be a hundred or so.” They appear because the subcutaneous fat has been absorbed, and the skin falls into folds. When the skin food or olive oil is applied the fattening qualities are nourished and they in turn build up the underlying tissues.

(Melendy, 1903, pp. 322-323)

An addition to this theme was to use a skin food to improve the skin’s ‘tonicity’. This idea suggested that wrinkles in the skin were due, in part, to a ‘feebleness of the nervous system’. Directly feeding the nerves in the skin with a skin food would revitalise them, tone up the skin and reduce the appearance of wrinkles. This notion promised that skin foods could have a tonic effect without being an astringent.

See also: Skin Tonics, Astringents and Toners

Animal, vegetable or mineral

In the past, it was commonly thought that animal or vegetable fats and oils were readily absorbed into the skin, whereas those derived from petroleum products were not (Harry, 1940, p. 53). Raisin seed, avocado, turtle and cod liver oils were all considered skin foods with lanolin (wool fat) being regarded as particularly efficacious due to its supposed similarity with skin sebum.

A flabby skin is one whose tissues have been deprived or emptied of their fatty substances, and anything which will fill them out again will remove, to a great extent, many of the wrinkles seen in faces showing skin of this description. A remedy, or rather a nourishment for the tissues, extensively used in England and coming into favorable notice here, is called “wool fat.” It was used three thousand years ago, and is a substance of a yellow color and a greasy nature, being derived by steeping the clippings of sheep’s wool in hot alcohol or spirits. It is very penetrating and quickly passes through the epidermis and restores the fatty substance to the empty tissues.

(Beauty: Its attainment and preservation, 1892, pp. 275-276)

Lanolin

Derived from sheep sebum, lanolin has been used as an emollient and skin protectant for thousands of years. Despite the fact that it is a wax rather than a fat or grease, it was considered an effective tissue-builder.

Tissue Builder Cream is to be used when the skin is normal or dry. The latter condition is clearly indicated by the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles.

Tissue builder cream should incorporate as one of its ingredients lanolin oil, as this is one of the best agencies we have to build up the tissues which is so necessary when a dry condition exists.(Meyer, 1936, p. 294)

A recipe for a lanolin skin food is given below:

White wax 1 ounce. Spermaceti 1 ounce. Lanolin 2 ounces. Sweet almond oil 4 ounces. Cocoanut oil 2 ounces. Benzoin (tincture) 3 drops. Orange flower water 2 ounces. Melt the first five ingredients together, take off the fire, and beat until nearly cold, adding, little by little, the benzoin, and lastly the orange flower water.

(Ayer, 1902, p. 162)

The tissue-building capabilities of lanolin were so well accepted that some beauty culturists suspected it of promoting facial hair and warned against its use on susceptible feminine faces.

Formulation

Unlike vanishing or cold creams there was no standard formulation for skin foods, as they were based on function not form. Such was the power of the term that it was applied to beauty products other than face creams, including soaps and face powders. In addition, as the idea of ‘feeding the skin’ developed in the twentieth century, other ingredients like plant extracts and vitamins were also described as being ‘nourishing’.

Given the ubiquity of this type of cosmetic in the early part of the twentieth century, it should come as no surprise that some skin foods were even made with petroleum products despite the fact that they not considered to be ‘nourishing’. As cosmetic companies of the time were not required to include ingredient lists in their labels it would be difficult for a consumer to realise the difference.

Muscle oils

As well as skin food creams, there were a number of water-free preparations made primarily from oils, such as castor, mineral, sweet almond, olive, soya bean, sesame and cottonseed (deNavarre, 1941). The common name for these oily skin foods was ‘muscle oils’ but they were also known as ‘tissue oils’, ‘anti-wrinkle oils’ and ‘oily skin foods’, an indication that they were often credited with nourishing qualities, above and beyond skin foods.

A rich nourishing oil for removing wrinkles and restoring the virility of the facial muscles, whether the faded or lined condition of the face is caused by illness, worry or advancing years. This penetrating oil feeds and fills out sunken features, softens lines and wrinkles about the mouth and eyes, and firms and strengthens the entire face.

(Elizabeth Arden promotional booklet, 1920s)

Generally speaking, muscle oils were applied over skin foods in areas that were considered in need of extra treatment, such as wrinkles, or on skin where muscles were perceived as being ‘weak’ and in need of ‘extra nourishment’. A recipe for a muscle oil is given below:

No. 111 Castor Oil (odourless) 35 parts Sweet Almond Oil 35 parts Peanut Oil Refined 30 parts Antioxidant qs Perfume qs 100 Directions: Mix the oils, add perfume, color and set aside a few days before filtering.

(deNavarre, 1941, p. 282)

See also: Muscle Oils

Night creams

Skin foods were ‘heavy’ creams. Some beauty culturists suggested they could be used as a foundation for powder but they were generally applied at night when used at home. This would give them time to ‘penetrate’ the skin and ‘nourish’ the underlying tissue

Women were already expected to cleanse their skin before retiring, so applying a skin food meant an extra step in the night-time skin routine. There was always the risk that women would simply skip the cleanser, so manufacturers of cold creams like Pond’s, were not above calling their product a skin food to fend off the competition.

Skin foods were to be left on the skin for some time to allow them to penetrate, so using them in a salon facial might present some problems. Therapists got around this by using techniques to ‘improve penetration’ such as massaging or patting the face, using the skin food as part of a mask or face pack, or first treating the skin to ‘open the pores’ to allow for easier access. These techniques are still in use today and similar arguments are often used to support them.

See also: Day and Night Creams

Regulation

In 1907, Globe Pharmaceutical was prosecuted in the United States under the Food and Drug Act of 1906, for misbranding a product called Sarotin Skin Food. When analysed, the product was found to be made from epsom salts coloured with a pink dye which would be unable to produce a “soft, velvety tint on the roughest of skin”. After pleading guilty the company owners were fined US$10. Incidents such as this led to a growing resolve in the United States to regulate cosmetics in the same way that drugs and food were controlled.

In 1938, the American Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&CA) was passed in the United States placing federal controls on the manufacture and sale of cosmetics and toiletries. In 1939, the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a statement to manufacturers, packers and distributors of cosmetics regarding false and misleading claims. The FDA was unhappy with cosmetics that gave the impression of having a food value or suggested they had drug-like effects. Amongst advertising terms that the agency thought were false or misleading were ‘rejuvenating cream’, ‘nourishing cream’, ‘skin conditioner’, ‘skin food’, ‘skin tonic’ and ‘tissue cream’.

Another popular manner of designating creams is to give them names, or make claims for them, that give the impression that they possess food value. Statements that a cream will nourish or feed the skin, strengthen the tissue, act as a tonic for the underlying nerves or muscles, or will rejuvenate, vitalize, vivify, banish fatigue, or the use of other terms which state or imply that the skin will be nourished are, for the most part, unfounded. When these claims are true the product is likely to be considered a drug rather than a cosmetic. Such names as “Skin Food,” “Tonic Food,” “Tissue Tonic,” or others of similar import which imply that the skin will be nourished by use of the same should not be used. Claims should be limited to temporary benefits only, and then should be kept within the accepted boundaries.

(deNavarre, 1941, p. 656)

After the FDA statement, the use of the phrase ‘skin food’ disappeared from American cosmetic advertising. However, it remained in use in other countries until they also strengthened their regulation of cosmetics. This meant that references to ‘skin foods’ continued to appear in magazine articles, beauty books and company advertising outside of the United States until the end of the 1960s at least.

The daily use of a night cream is essential at any time, but more especially when there’s a frosty nip in the air, so do remember to massage your face every evening with skin food.

(Mary Moore – Women’s Illustrated magazine, U.K., 1955)

Lubricating creams

The misleading nature of the advertising did not mean that using ‘skin food’ creams had no benefits. Their ‘heavy’ nature meant that they had a beneficial effect on dry skin, helping to keep it supple and soft. American manufacturers realised this and simply rebadged skin food creams as ‘lubricating’, ‘emollient’ or ‘night’ creams after 1938 with lanolin remaining a favourite ingredient.

Lubricating creams are formulated principally to apply oily emollients to skins that are deficient in oil. Because lanolin is derived from animal sources and contains some of the basic constituents that are secreted by the sebaceous glands of the human skin, it is a popular addition to this type of cream. In formulating lubricating creams it is highly desirable to bear in mind that they should possess such properties as ease of spreading, fine texture, good skin absorption, lack of stickiness and smoothness without too much oiliness.

… No reputable dermatologist will deny that lubricating cream, consistently applied, will keep a dry skin supple and prevent a scaly appearance. These results are enough to justify the existence of lubricating cream, and to warrant the cosmetic importance attached to it.(Thomssen, 1947, pp. 123-124)

The use of the term ‘lubricating cream’ had been around well before the 1938 Act. Some cosmetic chemists had questioned the claims of skin foods well before 1938, referring to them as lubricating creams instead. Chilson for example, titles his chapter on these creams ‘Lubricating (Tissue) Creams’ (Chilson, 1934) and includes a critique of any nutrient claims.

Much of the medical opposition to cosmetics is based upon unsupported claims for tissue cream, which really should be called lubricating cream. In spite of the vast amount of research which has been done on this product, there is as yet no evidence to show that tissue creams are capable of exerting more than a lubricating action. However, even if scientists had demonstrated that tissue cream can be absorbed through the skin and hence into the blood stream, they would have a still more difficult problem in demonstrating how anything absorbed at one point of the body can exert its action only at that point and nowhere else. It is evident that even if tissue cream could be absorbed through the skin, its action would not be confined to the face alone. As a matter of fact, assuming such absorption, the cream might exert its beneficial action on a portion of the body where such action would be undesirable! It seems therefore that in attempting to prove the fact of absorption, the trade is tilting at a wind-mill, because absorption is not required to demonstrate the value of tissue cream as an excellent skin lubricant.

(Chilson, 1934, p. 77)

Another tactic was to incorporate special ingredients into their skin creams – such as hormones, vitamins, royal jelly or turtle oils – and to label them as such, with the promise that these would improved the look and feel of the skin and reduce the signs of ageing. This had been going on since the early 1930s but gathered pace after the Second World War. Most of these additives eventually disappeared as companies concentrated on improving skin hydration, a process which eventually led to the widespread adoption of moisturisers during the 1960s.

See also: Royal Jelly, Hormone Creams, Oils and Serums, Placental Creams and Serums and Turtle Oil

Although the use of the term ‘skin food’ had a much longer run outside of the United States – until new regulations were enforced there as well – the idea of a skin cream, lotion or serum being able to feed the skin has never really died. Many cosmetics are still promoted as having the ability to replace something in the skin that has diminished with age. One only has to look at the number of skin-care products that suggest that they replace collagen, elastin, hyaluronic acid or some other age-diminishing component of the skin to see that this is the case.

First Posted: 20th September 2010

Last Update: 24th June 2022

Sources

Askinson, G. W. (1923). Perfumes and cosmetics their preparation and manufacture. A complete and practical treatise for the use of the perfumer and cosmetic manufacturer covering the origin and selection of essential oils and other perfume materials, the compounding of perfumes and the perfuming of cosmetics, etc. London: Crosby Lockwood and Son.

Ayer, H. H. (1902). Harriet Hubbard Ayer’s book of health and beauty. New York: King-Richardson.

Browning, E. H. (1898). Beauty Culture. London: Hutchinson & Co.

The Butterick Publishing Company. (1892). Beauty: Its attainment and preservation. New York: Author.

Chilson, F. (1934). Modern cosmetics. New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston: D. Van Nostrand Company.

Harry, R. G. (1940). Modern cosmeticology. The principles and practices of modern cosmetics. Brooklyn, NY: Chemical Publishing Company.

Melendy, M. R. (1903). Perfect womanhood for maidens-wives-mothers. A book giving full information on all the mysterious and complex matters pertaining to women.

W. M. Meyer Co. (1936). The cosmetiste: A textbook on cosmetology with special reference to the employment of electricity in the care of the hair, scalp, face, and hands, also permanent waving and hair curling (9th ed.). Chicago, Ill: Author.

Thomssen, B. S. (1947). Modern cosmetics (3rd ed.). New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

Verni, M. (1946). Modern beauty culture (2nd ed.). London: New Era Publishing.

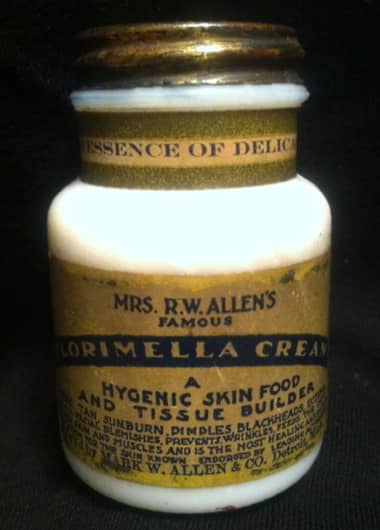

Mrs. R. W. Allen’s Florimella Cream. “A hygienic skin food and tissue builder. Cures tan, sunburn, pimples, blackheads, eczema and all facial blemishes, prevents wrinkles, feeds the impoverished skin”.

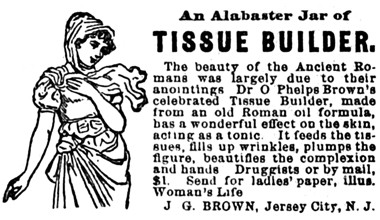

1892 Dr. Brown’s Tissue Builder.

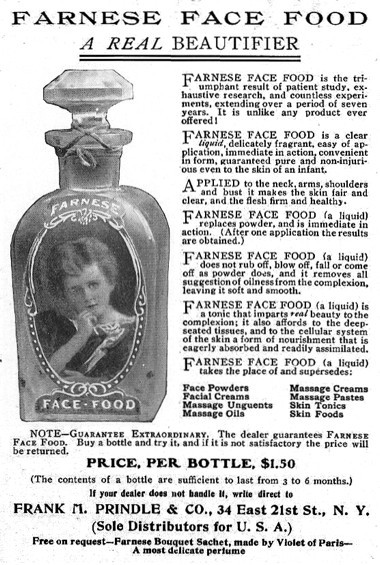

1905 Farnese Face Food.

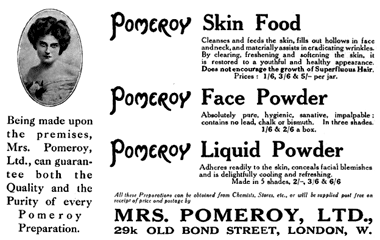

1912 Pomeroy Skin Food.

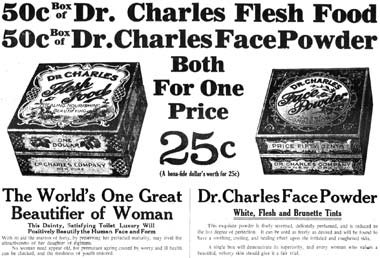

1912 Dr Charles Flesh Food. “Healing, nourishing and beautifying.”

1913 Helena Rubinstein Valaze Beautifying Skin Food.

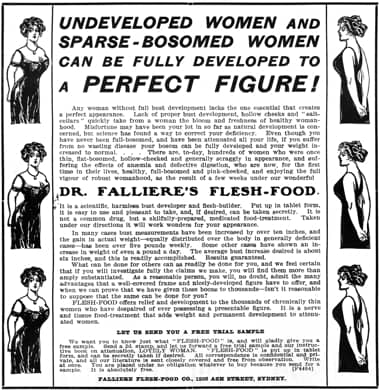

1913 Dr. Falliere’s Flesh Food.

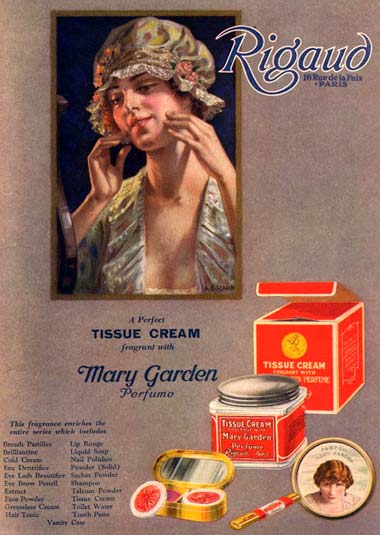

1920 Rigaud Tissue Cream.

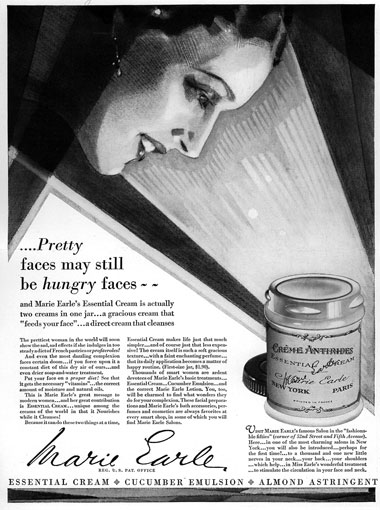

1928 Marie Earle Essential Cream.

1930 Coty Culturiste Creations including Tissue Cream.

1935 Du Barry Beauty Preparations including Du Barry Special Skin Food.

1939 Tokalon Biocel Skin food.

1940 Luxor Skin Tissue Cream to relieve skin dryness.

1948 Yardley Skin Food (Britain). This type of labelling was banned in the United States after 1938.

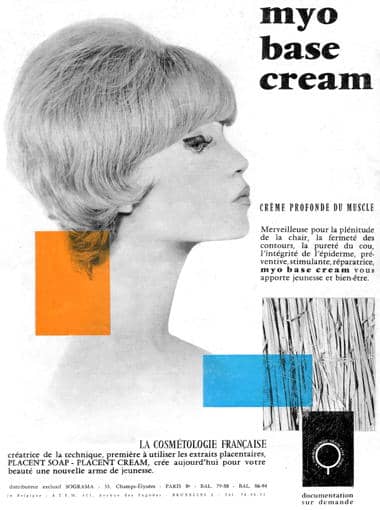

1962 Myo Base Cream (France). The idea of building up the skin with creams was still taking place in some countries in the 1960s. This cream suggested it was ‘wonderful for the fullness of the flesh’.