Revlon and ‘The $64,000 Question’

On June 7, 1955, ‘The $64,000 Question’ premiered on CBS-TV. Chrysler, the Lewyt Vacuum Cleaner Company and Helena Rubinstein had previously declined to sponsor the show. Charles Revson of Revlon agreed to do so but only very reluctantly.

[Charles Revson] was getting awfully tired of investing in one “stiff” of a TV series after the next. He had a natural bias against television advertising anyway. It was black and white, and he was selling colors. Nor could he control TV ads the way he could control print. This new medium was not his dish of wax, as he would say.

(Tobias, 1976, p. 145)

The decision to have Revlon sponsor ‘The $64,000 Question’ was to have a dramatic effect on both Revson’s and the Revlon company’s fortunes.

Hazel Bishop

Although Revson preferred print advertising, he had a problem that could only be fixed through television; that problem was Hazel Bishop. Between 1950 and 1953 Hazel Bishop had managed to capture 25% of the American lipstick market primarily through advertising its ‘Long Lasting Lipstick’ on television shows like ‘This Is Your Life’.

Revlon had introduced products to compete, including Indelible-Creme Lipstick in 1951 and Lanolite Lipstick in 1954, but television advertising continued to give Hazel Bishop the edge. Hazel Bishop sales were so reliant on it that some industry insiders went so far as to refer to the business as a television program rather than a cosmetics company (Drug & Cosmetic Industry, 1958).

See also: Hazel Bishop

‘The $64,000 Question’

The idea for the half-hour program was simple. Based on a radio quiz show, ‘Take It or Leave It’, contestants would be asked a series of questions with the prize money – starting at $64 – doubling after each correct answer. If contestants reached $1,000 they then appeared weekly to answer only one question, brought in under secure guard; at $4,000 they were placed in an isolation chamber; at $8,000 and beyond they were given a consolation prize of a Cadillac sedan if they answered incorrectly.

Within four weeks the show was number one in the ratings and, to all intents and purposes, the nation came to a standstill every Tuesday night at 10.00 p.m.

Critics were already hailing it as the hottest show of the century. They proved to be right. Within weeks the $64,000 Question program held 80% of the audience, had the highest TV ratings ever secured by a continuing series, and was winning front page headlines across the country. Theatres interrupted their films to report on the progress of contestants. Telephone calls were virtually nil while the show was on the air.

(Abrams, 1977, p. 52)

Revlon pulled out all stops to capitalise on the public interest.

Stores readily opened their counter space for Revlon products. New products by the dozen were introduced, all but one or two successfully. And why not? The advertising cost per thousand homes was virtually less than any advertiser on network television.

Moreover, the program received publicity in magazines, newspapers and on broadcast media which dollars alone could not purchase. Carl Erbe, the public-relations firm servicing Revlon, performed magnificently, milking every inch of space they could get and winning brand mentions where ordinarily such commercialism is verboten.(Abrams, 1977, pp. 58-59)

The effect of ‘The $64,000 Question’ on Revlon sales was remarkable. In 1954 sales had been $33,604,000; the following year – although the program had only been running since June – sales jumped to $51,646,000; they hit $85,767,000 in 1956 and reached $110,363,000 in 1958, the year the show went off the air (Abrams, 1977, p. 64).

Every item featured on the show is selling at a rate of 75-100% over normal, reports account executive Whitney.

Frosted Nail Enamel is up 300%.

Living Lipstick is going 100% better than expected since it was launched on the opening broadcast. Revlon fell so far behind on orders for this item, it yanked the TV commercial by September. In October it was still about a month behind.

Satin Set is doing about 75% better than expected.

Lanolite Lipstick was featured only during the first month, yet maintains an increase of nearly 40%.

Revlon’s Eye Makeup is only mentioned in the opening billboard of the program, yet its sales have jumped 45%. Similarly, Aquamarine Lotion, normally a cold-weather item, increased 10-15% through the summer.

In lipsticks, Revlon, long the leader, is leaving the competition far behind. In the spring, a national survey showed it running neck and neck with Hazel Bishop for first place in share of market. Revlon’s share was about 25%, Bishop’s about 21%.

By the end of July, Revlon’s market share is said to have passed 30% while Bishop’s had fallen to 14%. The next surveys are expect to show Revlon moving toward 40%.(Television Magazine, 1955, p. 86)

The repercussions for Hazel Bishop were dire. Early in 1956 its board chairman, Raymond Spector announced that the company had made a loss, blaming it primarily on the success of ‘The $64,000 Question’. Hazel Bishop would never regain its early momentum.

What must have been particularly rewarding for Charles Revson was that, even with the prize money, the program averaged out costing around $14,000 per show, about half of the $27,000 it cost Hazel Bishop to make an episode of ‘This Is Your Life’. Another $40,000 went for each half hour of network broadcast time (Tobias, 1976, p. 149) but even there, Revlon made sure it got its money’s worth.

Program adjustments

Although ‘The $64,000 Question’ went to air live from the CBS-TV Studio 52 in New York, it was not owned by CBS, but was developed by Louis G. Cowan, Inc., an independent producer. This state of affairs was of great benefit to Revlon – the sole sponsor – as it allowed them to exert a considerable degree of influence. Martin Revson [b. 1910] was given the role of looking after the show and at the weekly meeting with the production company and the advertising agency, raised changes that Revlon wanted introduced.

One adjustment made after ‘The $64,000 Question’ went to air was the replacement of the two 90-second commercials by three 60-second ones (Abrams, 1977, p. 52). This allowed more products to be promoted and – as most of the commercials were broadcast live – enabled Revlon to crib more free airtime from the network.

Doing the commercials live had a number of advantages, not least of which was that it allowed Revlon to steal television time. Each of Revlon’s three commercials per show was supposed to run one minute. Few, if any, ran less, and a great many ran longer. Says a key figure from that period, still with Revlon: “We would run ‘sixty-second’ commercials for three minutes and there was nothing they could do to stop us.

CBS naturally screamed its head off – but only so loud. This was a very hot property they had, and they didn’t want to see it moved to NBC.(Tobias, 1976, p. 148)

Revlon also made good use of the reports it received from their nationwide system of demonstrators each week the day after the show went to air.

Core of the system are 600 Revlon demonstrators employed in department stores throughout the country. Each keeps a detailed inventory record. At the close of business the day after the show, she telephones the following information to the company:

Sales for the day;

Average daily sales the preceding week;

Sales for the same day of the preceding week.(Television Magazine, 1955, p. 86)

Feedback from the demonstrators enabled Revlon to quickly gauge the effect of product demonstrations on ‘The $64,000 Question’ and make adjustments; for example, feedback from the demonstrators was the reason Revlon changed the commercial slots on the show from fixed to flexible.

After the third show, it was noted that Satin Set, which had been advertised, was not moving. Moreover, nobody seemed to remember that it had even been on. A rehash of the program revealed that it had been carried immediately after the policeman, O’Hanlon, had won $32,000.

“It was soon clear to us,” says agency v.p. and TV head Walter Craig, “that we had made a psychological blunder in slotting the Satin Set commercial. There was such audience relief when O’Hanlon won his $32,000 that the viewer simply could not be held for a commercial. The tension had snapped momentarily. People were busy discussing what had happened.”

The moment the Revsons realized what was up, related Craig, they issued the following instructions to the agency: Henceforth, there would be no fixed positions for the commercials. Walter Craig would sit in the control room and determine during the show the proper moments for the pitches.(Television Magazine, 1955, p. 51)

Post 1955

It was of little long term consequence to Revlon that ‘The $64,000 Question’ went off the air in 1958. By then, Revlon had moved into a level of operations that put it beyond the reach of most of its rivals.

It may be argued that The $64,000 Question was the difference between Revson’s becoming just another successful businessman and his becoming a superstar. Up until this time, Revlon had risen to the level of its competitors, but did not dominate the field, except in nail polish. It had to fight costly battles with competitors. It did not have huge advantages of scale. Profits were modest. The company was not home free. …

The Question raised Revlon sales, profits, and consumer awareness so dramatically as to put it miles ahead of its competitors. And that sort of edge tends to be self-perpetuating, or even self-expanding. The rich get richer. The companies with the most resources, other things being equal (not better, just equal), can swamp the competition.

… Helena Rubinstein, Max Factor, Coty, and Hazel Bishop, which had all been at least within striking distance of Revlon before The Question went on the air, were left bitterly in the dust. Revlon was number one in lipstick, number one in hair spray, number one in nail products, and number one in makeup.(Tobias, 1976, p. 148)

Revson’s testimony during the quiz show scandal hearings outlines some of the benefits the company got from its quiz shows.

Mr. LISHMAN. We have the figures here to refresh your memory. Mr. Revson, I have here a list of cosmetic companies listed on the stock exchange with a net sales analysis. Among the New York Stock Exchange companies shown on this list are Revlon, Inc.; Coty, Inc.; Max Factor, Inc.; Helena Rubenstein [sic.] & Co., and Hazel Bishop.

Mr. Revson. I think Hazel Bishop is only one of the Atlantic companies listed at that time. Helena Rubenstein and Max Factor are American Stock Exchange, if that makes any difference.

Mr. LISHMAN. Let us look at the figure for 1953.

I will show you this so you can follow.

If you will start with the year 1953, and as shown here the net sales for Revlon were $28,398,065?

Mr. Revson. Yes, sir.

Mr. LISHMAN. The net sales for Coty were $19,590,671; for Max Factor, $19,021,041; for Helena Rubenstein, $20,473,124; for Hazel Bishop, $9,908,804.

Mr. Revson. Yes, sir.

Mr. LISHMAN. At that time your dominance was not as great as it is today; is that correct, among the companies listed here?

Mr. Revson. I have to study that a minute.

Mr. LISHMAN. I will read the bottom figures.

Mr. Revson. No. I am wondering at the 1958 figures. I see the nearest competitor is Max Factor with $45 million.

Of course, if you take out the 15 million or so for Knomark shoe polish, you come down to what, $96 million, about. So it would be a little less than 50 percent more.

Mr. LISHMAN. Putting it this way: In 1953, you were approximately $8 million ahead in net sales of your nearest competitor, Helena Rubenstein; is that not correct?

Mr.Revson. That is what the figures say. I am taking the figures.

Mr. LISHMAN. In 1958, excluding the shoe polish sales, your nearest competitor had rounded net sales of $45 million and you had rounded net sales of $96 million?

Mr. Revson. Yes.

Mr. LISHMAN. In other words, in 1958, you were twice as good as your nearest competitor?

Mr. Revson. Yes.

Mr. LISHMAN. Do vou attribute this to the “$64,000 Question” and “$64,000 Challenge” programs?

Mr. Revson. It helped. It helped.(Investigation of television quiz shows, 1959, p. 811)

Charles Revson had also made a great deal of money. Revlon had gone public on December 7, 1955, six months after the debut of ‘The $64,000 Question’. The shares were floated at $12 but hit $30 within a few weeks and were split two-for-one in 1956. By 1959, the year after ‘The $64,000 Question’ was cancelled, Charles Revson was the majority shareholder in Revlon and a millionaire many times over.

See also: Revlon

Updated: 17th March 2014

Sources

Abrams, G. J. (1977). That man. The story of Charles Revson. New York: Manor Books.

Barnouw, E. (1970). The image empire. A history of broadcasting in the United States. Volume III—from 1953. New York: Oxford University Press.

The drug and cosmetic industry. (1958). New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Fox, S. R. (1984). The mirror makers: A history of American advertising and its creators. New York: Morrow.

Investigation of television quiz shows. Hearings before a subcommittee on interstate and foreign commerce. House of representatives. Eighty-sixth congress. Part 2. (1959). Washington: Government Printing Office.

MacDonald, J. F. (2009). One nation under television. Retrieved June 24, 2013, from http://www.jfredmacdonald.com/onutv/

Television Magazine. New York: Frederick Kugel Company, Inc.

Tobias, A. (1976). Fire and Ice: The story of Charles Revson—the man who built the Revlon empire. New York: William Morrow.

TV’s biggest success. Here’s what makes “$64,000 Question” viewers go out and buy Revlon products. (1955). Television Magazine. XII(11), 50-51, 86-87.

Hal March [1920-1970] in good times, before the quiz scandal affected his career. Allegations of cheating on another quiz show, ‘Twenty-One’, resulted in an investigation by the Congress Subcommittee on Legislative Oversight. The committee determined that contestants on ‘Twenty-One’ were given their questions and answers in advance.

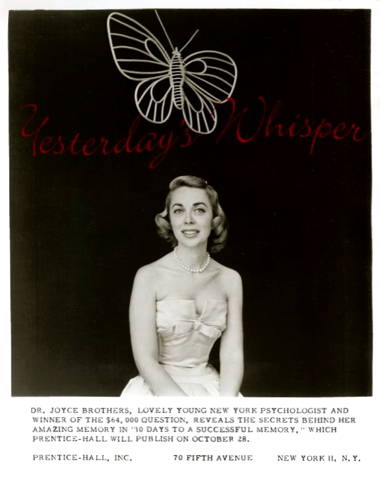

‘The $64,000 Question’ was ‘controlled’ rather than ‘rigged’ like ‘Twenty-One’. Favoured contestants on ‘The $64,000 Question’ were given questions the producers thought they would be likely to get right, while others, considered ‘duds’, were given questions it was thought likely they would get wrong. The process was not perfect. Dr. Joyce Brothers, for example, who was regarded as a ‘dud’ by the Revsons, managed to answer every question given to her on her subject area, boxing, and made it all the way to answering the $64,000 question correctly.

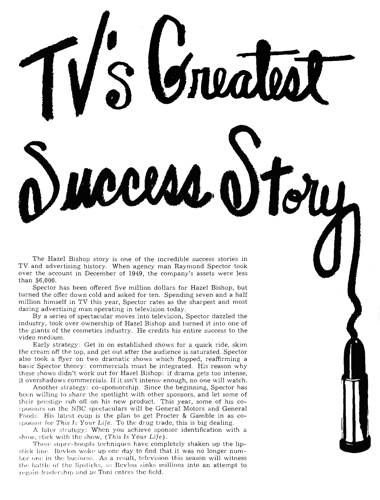

An article from a 1954 September issue of ‘Television Magazine’ on the Hazel Bishop success story. Just over a year later the situation was very different.

Walter Craig, vice president in charge of radio and television for Norman, Craig & Kummel. The man who brought ‘The $64,000 Question’ to Revlon. It might be thought Charles Revson would be grateful but within three months of the first show going to air, Norman, Craig & Kummel had lost the Revlon account (Abrams, 1977, p. 167).

The set of ‘The $64,000 Question’. The isolation booth is centre-stage with Hal March on its camera-right and the hostess – who seems to be Wendy Barrie [1912-1978] – is on its camera-left ushering in a contestant – possibly Peter Frenchen. The booth looks like it is being checked to make sure nothing is amiss. The Cadillac sedan consolation prize is parked camera-left and the security guard with the locked question box is camera-right.

1955 Charles Revson presenting the first $64,000 check to Richard S. McCutchen, a Marine Captain whose subject was cooking. He was watched by 55 million viewers.

1958 Hal March promoting Revlon lipstick.

1958 Revlon Satin Set commercial from ‘The $64,000 Question’. The presenter appears to be Barbara Britton [1919-1980].

1959 Charles Revson [1906-1975] testifying during the quiz show scandal hearings.

Dr. Joyce Brothers [1927-2013]. Despite the best efforts of the Revson brothers to get rid of her, she successfully answered the $64,000 question.