Hazel Bishop

Founded in 1948 on a single product, a no-smear lipstick, the Hazel Bishop Company had a meteoric rise in the United States in the 1950s due to extensive advertising on network television. However, its heyday did not long outlast the involvement of its founder, Hazel Bishop.

Hazel Gladys Bishop

After graduating in 1929 from Barnard College (Columbia University, N.Y.) with a degree in chemistry, Hazel Bishop hoped to go into medicine. The stock market crash of 1929 put paid to her plans to become a doctor and she opted instead to do postgraduate work in Columbia’s College of Physicians & Surgeons. In 1935, she took a position as a research assistant to Dr. A. B. Cannon, Director of Dermatology at the Columbia Medical Center. She then worked as an organic chemist for the Standard Oil Development Company (1942-1945) and for the Socony-Vacuum Oil Company (1945-1950).

During her time with A. B. Cannon in the 1930s, Hazel gained some experience with the business side of cosmetics. Cannon was one of the founders of Almay, a hypoallergenic cosmetics brand established in 1931. In the 1940s, Hazel got interested in lipsticks. Bright red lipsticks had been popular during the Second World War but she found them less than satisfactory and began work on producing a “nondrying, nonirritating, long-wearing” form. After conducting over 300 different experiments she eventually developed one that she thought was suitable.

In 1948, Hazel Bishop met the lawyer Alfred Berg who was planning to bring the French lipstick Rouge Baiser back into the American market. Hazel thought she had a better product and, after Berg agreed to provide venture capital, they founded the Hazel Bishop Corporation in 1948.

Lasting Lipstick

Hazel Bishop’s Lasting Lipstick used bromo acid dyes to get the lipstick to last. These had been around since the 1920s and there were about a dozen different types in use by 1950 (deNavarre, 1975). The main drawback with using stains was that they caused lip ‘dryness’, a problem that worsened as the amount used increased. Hazel offset some of the dryness with lanolin but she did not completely solve the problem.

The lipstick also required a degree of effort on the part of the user to achieve the long-lasting result. Women were expected to wait for the lipstick to set and then blot off the excess in order for it to be ‘kissproof’.

As well as using bromo acids, Hazel was also concerned with the adherence of the pigments in her lipstick. As she noted in a 1953 letter to Maison G. deNavarre [1909-1983], she considered these an important part of the formulation.

The longer lasting properties that are obtained only in part through greater staining of the lips. They are also obtained in part by the pigments being embedded in a basic composition which adheres more tenaciously to the lips than was true in the old conventional formulas. Thus the smear-proof lipstick derives its color from pigment plus stain, rather than from stain alone. This is important because, without pigment, the lip application has a “thin water-colored” look which, in my opinion, is neither satisfactory or desirable to the American women.

(Hazel Bishop letter to deNavarre at AP&EOR, 1953)

See also: Maison G. deNavarre

Removing the stain was another problem. Even if soap and water or cold cream was used to remove the lipstick at night, the lips would still be coloured the next morning. Hazel Bishop turned this problem into an asset by suggesting that you would ‘Wake up Beautiful’, an idea also used by other makers of long-wearing lipsticks such as Coty and Revlon.

Hazel Bishop Long Lasting Lipstick originally came in six colours: Pink, Red Orange, Real Real Red, Medium Red, Secret Red, and Dark Red with other shades, such as Light Pink and Light Red, added later. Hazel chose descriptive rather than fantasy names for her lipstick shades believing that “women want color information when they buy a lipstick, not a prose poem” (Daytona Beach Morning Journal, 1951). This idea was not without precedent. Tangee lipsticks, for example, also used lipstick names such as Red-Red (1940) and Medium-Red (1942) but Hazel Bishop applied this principle consistently over the whole range.

See also: Tangee

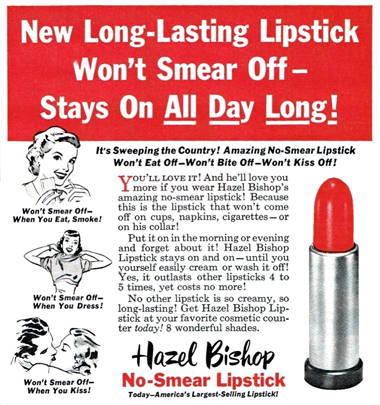

Commercially manufactured by Kolmar Laboratories, the lipstick was successfully trialled in 1949 during a fashion show at Hazel’s alma mater (Barnard College) before it went on sale in 1950. Newspaper space was purchased which advertise that the lipstick will not “eat off, bite off or kiss off”, a tag-line that was similar to the “you can’t drink off, smoke off or swim off” line used by Vivaudou to promote their green, indelible Viva-Caprice Lipstick (1940), or the “doesn’t easily eat off, drink off or kiss off” claim made by Richard Hudnut for its Du Barry Lipstick (1949).

The introduction of Hazel Bishop Long Lasting Lipstick proved to be very successful; Lord & Taylor (New York) sold out of the line in one day. In 1950, sales approached US$50,000 but the company was operating at a small loss so the partners turned to Raymond Spector and his New York advertising agency to help with a national expansion.

Raymond Spector

Spector agreed to help market Lasting Lipstick in return for Hazel Bishop stock. Through his advertising agency, the Raymond Spector Company, Spector advertised the lipstick aggressively, following a newspaper campaign with extensive advertising on radio and television.

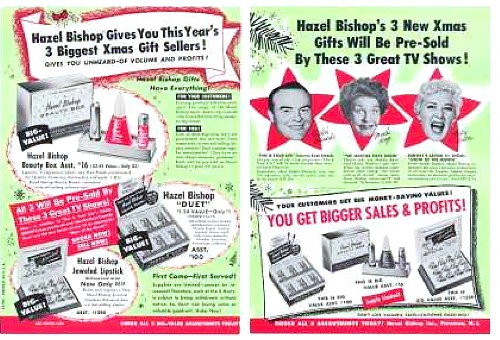

Above: 1951 Trade advertisement for Hazel Bishop.

Starting, in 1950, with spot radio announcements in 57 markets, followed by spot television announcements on three television shows – Kate Smith Show (National Broadcasting Company), Cavalcade of Bands (Du Mont) and Cavalcade of Stars (Du Mont) – the company then began sponsoring a range of radio and television programs including ‘Inside News Of Hollywood’, ‘I Confess’, ‘Candid Camera’, ‘This Is Your Life’ and ‘The Martha Raye Show’. According to Spector this was to ensure maximum penetration.

Since its TV debut, the lipstick company has picked up—and dropped—seven different shows. But until recently, the reason has always been the same, according to Raymond Spector, president of the firm’s agency.

“After six months of using a show,” Mr. Spector explained, “we’ve skimmed the audience. Lipstick is used by all women. Our policy is to shift every six months, so that we hit different groups. That’s why we dropped Stop the Music to pick up NBC-TV’s Cameo Theatre.(Television Magazine, 1952)

Spector’s move into television was initially very successful. By 1953, Hazel Bishop sales had reached US$10 million dollars. Lasting Lipstick – also referred to as No-Smear Lipstick until the Federal Trade Authority (FTA) curtailed the unrestricted use of the term in 1953 – had captured 25% of the lipstick market and the company had a pre-tax profit of nearly US$2 million.

Above: Stills from a Hazel Bishop lipstick commercial shown on ‘Beat the Clock’. The lipstick is drawn on the hand along with another ‘leading brand’ and then both are rubbed off. The Hazel Bishop lipstick remains on the hand whereas the other brand comes off.

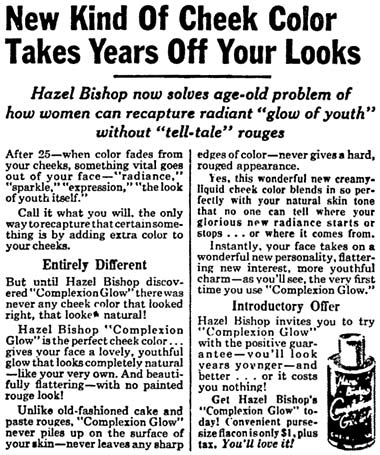

In 1952, Hazel Bishop added Complexion Glow, a liquid-creme rouge, and followed this with Long-Lasting Nail Polish in 1953. These sold well alongside the lipstick which was reformulated in 1954 after it was forced to drop its ‘no-smear’ tag by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and replace it with ‘long-lasting’ or ‘no-smear type’.

Above: Vera Francis [1925-2014] doing a promotion for Hazel Bishop.

No-Smear/Long-Lasting Lipstick: “[W]ont eat-off, bite-off or kiss-off”. Shades: Pink, Red Orange, Real Real Red, Medium Red, Secret Red, and Dark Red, with other shades such as Soft Pink, Pastel Pink, Deep Pink, Coral, Light Red. Later shades included: Rose Red (1953); Pink Minx (1956); and Venetian Violet, Lido lilac, and Monaco Orange (1957).

Complexion Glow: “[D]oes away with pasty, pale look … gives your cheeks a natural looking glow”. Shades: Pink Glow, Coral Glow, and Rose Glow.

Long-Lasting Nail Polish: “[L]asts longer than you ever dreamed possible”. Shades: Dusty Pink, Pastel Pink, Deep Pink, Coral, Real Real Red, Medium Red, Rose Red, Dark Red, Natural, Iridescent Pearl, and Iridescent Pink. Later shades included Pink Minx (1956).

See also: American Lipstick Wars

However, to achieve these results Spector was spending over one-third of the company’s gross income on advertising, most of which was in television. By 1953, Hazel Bishop was the largest television cosmetics advertiser in the United States and, in 1954, spent over US$2.3 million on television advertising (Television Magazine, 1954).

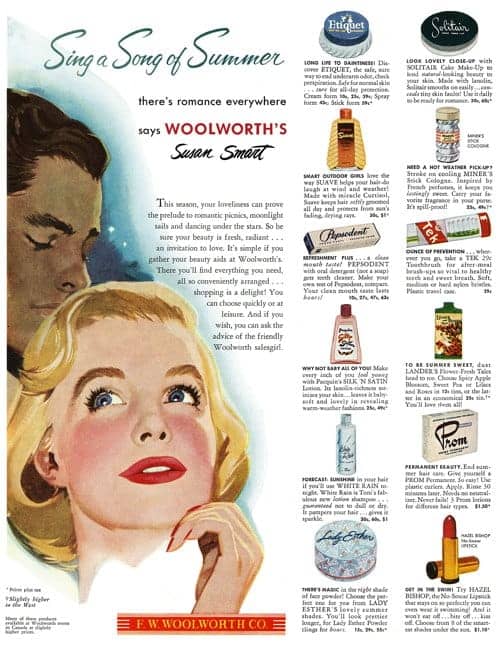

Spector’s marketing strategy was focused on sales rather than margins. As well as extending the product line, he distributed Hazel Bishop products through big syndicated low-cost stores like Woolworth’s rather than department stores (Drachman, 2002).

Above: 1952 Woolworth’s advertisement with Hazel Bishop Lipstick.

Spector was making a good deal of money from Hazel Bishop. In 1953, he received US$37,000 as chairman of the board of the Hazel Bishop Corporation and collected revenues from his agency, which made over US$600,000 from Hazel Bishop in that year. The more the company spent on advertising the more his agency earned – a clear conflict of interest – a situation that was well known in the wider cosmetics industry, both in the United States and abroad.

The Hazel Bishop success story is also a case of entering a highly saturated market – lipsticks. Using an imaginative television programme, spending large sums on television, and proclaiming that its lipstick was indelible (later the government authorities rule that this and similar sticks were to be called ‘indelible type’, a distinction made long after the first flush of success and one that is probably having little effect on the consumer), this firm had a meteoric rise. Leaving in its trail some of the best known names on the American cosmetic scene, the Hazel Bishop lipstick captured a share of the market that few considered possible for a new company. But at what cost? At the cost of an advertising appropriation far, far greater than another firm would consider economical for its return. Yet, because of a partial interlocking ownership between this company and the agency handling the advertising, a great part of the profits ‘lost’ to the company were picked up by that agency.

(Perfumer & Essential Oil Record, 1954)

Separation

Hazel’s difficulties with Raymond Spector began soon after he joined the company and, after resigning as President of Hazel Bishop in 1951, she took out a lawsuit against the Hazel Bishop Corporation, the Raymond Spector Company and others, charging them with mismanagement and the diversion of assets. Spector turned to his attorneys – Gordon, Brady, Caffrey and Keller – and his former attorney Milton E. Mermelstein for help. Some of these lawyers took shares in the company and served in official capacities.

With the help of his lawyers, Spector tied up the intellectual property of the company. In an agreement backdated to 1950, Hazel was hired to provide consultancy and promotional services for a period of two years. For this she received US$12,000 per year and a percentage of the product sales, not to exceed US$20,000. As part of this agreement, she agreed to allow her name to be used in perpetuity by the corporation and to refrain from endorsing the retail sale of any other product for a period of 25 years. This appears to have been the more important part of the agreement, as she had very little to do with the creation of Hazel Bishop products other than the original lipstick.

Above: 1953 Hazel Bishop talking to Robert L. Moore, Bureau of Advertising, American Newspaper Publishers Association.

Spector also recapitalised the Hazel Bishop Corporation, thereby reducing the overall proportion of shares owned by Berg and Bishop. He then bought more company stock including Alfred Berg’s shares. In 1954, with legal bills mounting, Hazel also sold out after signing an agreement in which she reaffirmed all previous covenants. She received US$310,000 for services rendered and for her 200 shares which were by then only 8% of the total company stock.

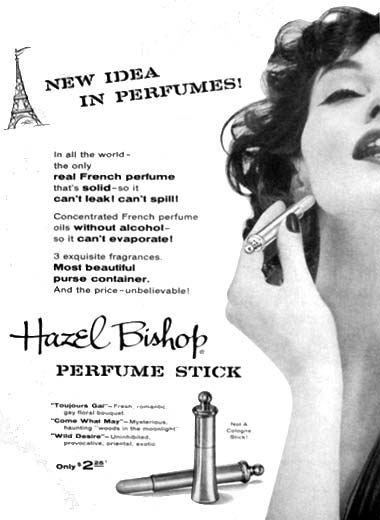

Hazel went on to have a succession of successful careers as a consulting chemist, market analyst and teacher. Her only dealings with the Hazel Bishop Corporation after 1954 began in 1956 when she personally endorsed Miss Perfemme, a solid perfume stick she had developed. She was taken to court by the Hazel Bishop company in 1957 for violating the terms of her agreement with them and, after a long process of counterclaim and appeal, lost the case in 1963.

Problems

The year 1954 was a watershed for the Hazel Bishop Corporation. Sales were levelling off and, more importantly, profits were declining. The following year it would make a loss, leading to it failing to declare its regular quarterly dividend for the first time. Spector noted that the company had experience a 25% increase in costs, part of which was due to US$500,000 spent on developing its own manufacturing operations, but clearly the bulk of the costs were related to television advertising that was not generating sales.

Spector had attempted to enter into an agreement with the Toni division of Gillette, to get cash in return for the sale of intellectual property, but the deal had ended up in litigation. He was also having trouble with the television networks over programming decisions and costs, particularly those associated with a few ‘stinkers’ he had sponsored at the National Broadcasting Company (NBC). Like the other networks, NBC was trying to dominate programming through its own ‘spectaculars’ or ‘specials’. It also increased the price of air-time so that it was prohibitively expensive for a company to be the sole sponsor of a show. As television was both the lifeblood of, and a major cost for Hazel Bishop, one can see why Spector was upset. In late 1955, he even went as far as temporarily switching his television budget to radio and newspapers (Fox, 1997). Unfortunately for him and the company, 1955 was also the year that Charles Revson of Revlon had a stoke of good luck.

Revlon

Charles Revson [1906-1975] – who founded Revlon in 1932 and had been in lipsticks since 1939 – became concerned about Hazel Bishop as its sales climbed and it diversified into other product lines. Like others, Revson countered Hazel Bishop’s No-Smear Lipstick by introducing an Indelible-Creme Lipstick (1951) and then Lanolite Lipstick (1954). However, it was through television that he did Hazel Bishop real damage.

Revlon had been unsuccessfully investing in television shows and Charles Revson was loathed to do so again. However, in 1955, he was persuaded, much against his better judgement, to sponsor the independently produced ‘The $64,000 Question’ that went to air on the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) on June 7, 1955. Within four weeks it was number one in the American ratings and the Revlon products it featured experienced sales increases of up to 500% (Tobias, 1976, p. 146). By 1956, Revlon’s proportion of lipstick sales in the American market had gone from 15% to 28% while the proportion sold by Hazel Bishop declined from 28% to 24% (Broadcasting Telecasting, 1956). This might not seem like a huge drop but it was enough for Hazel Bishop to slip into an operating loss.

See also: Revlon and the $64,000 Question

Spector saw the ‘The $64,000 Question’ as the main cause of the company’s problems. In 1956, he announced to the board of Hazel Bishop that the operating loss was due to the airing of a new television program sponsored by a competitor. Spector had used television to generate remarkable sales for Hazel Bishop and now it was being used against him. What must have been particularly galling for Spector was that ‘The $64,000 Question’ was costing Revlon a lot less money (Tobias, 1976) than he was paying for television advertising and Revlon was its sole sponsor. Worse was to follow.

Acquisition

In 1955, following stock sales by some of his allies on the board, Spector lost his leadership role in the company, a position he would not regain until 1957. By then, Hazel Bishop sales had dropped to US$10 million (from their high of US$12 million in 1954) and the company had experienced three years of losses of over US$1 million. This forced the company to trim its operating costs and reduce its advertising budget. Realising he needed to continue to advertise on television but did not have the budget to pay for it, Spector exchanged his 60% stake in Hazel Bishop for shares in C&C TV in 1958. The sale was noted with some cynicism in the wider industry.

The company has been know for some time now not as a cosmetic company, but a television program. This seems to clinch the definition.

(Drug & Cosmetic Industry, 1958)

C&C TV – which subsequently changed is name to Television Industries Incorporated – owned the RKO film library and distributed the films without charge to television stations in return for free advertising spots. They had been using this system to advertise a cola drink but had trouble finding sufficient products for all of their spots so their acquisition of Hazel Bishop helped fill some gaps. Henceforth, the presence of Hazel Bishop products on television would be through this spot barter system rather than through network television (Broadcasting telecasting, 1958).

Diversification

In 1957, Hazel Bishop reformulated its lipstick, marketed it as as Formula 77 in twelve shades including Real Real Orange, Fire Power, and Bermuda Coral. The number 77 was taken from the company’s claim that 77% of women have sensitive lips. It contained lip softeners and was ‘extra creamy’ so was in line with other creamy lipsticks introduced in the United States in the late 1950s.

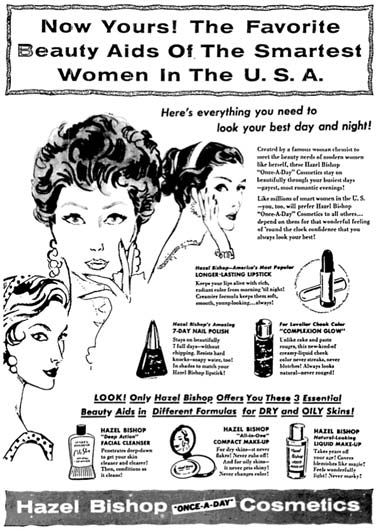

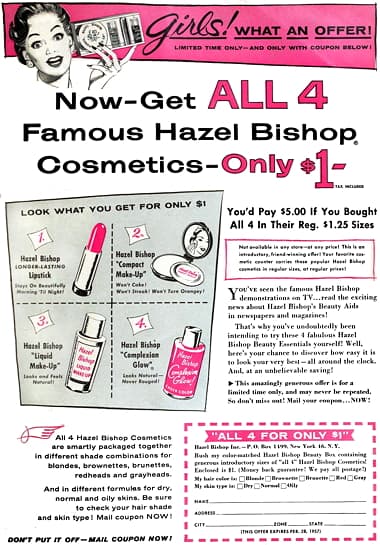

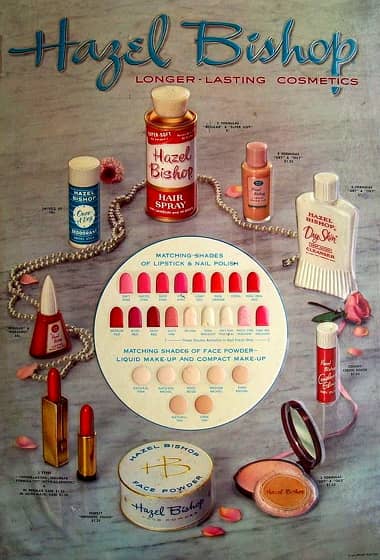

Hazel Bishop also diversified its product line so that by the end of the 1950s it included foundations, face powder, hairspray, deodorant, eye make-up and perfume.

Complexion Glow: “Unlike cake and paste rouges … never streaks, never blotches! Always looks natural—never rouged!”

Compact Make-up: “Foundation plus powder. Never gets shiny! Never changes color! Comes in a special formula for dry skin. Entirely different formula for oily skin!” Shades: Natural Pink, Rose Beige, Natural Rachel, Medium Rachel, Dark Rachel, Natural Tan, and Dark Tan.

Liquid Make-up: “Covers blemishes like magic! Feels wonderfully light! Never masky! Never greasy! Different formulas for dry and oily skins!”

Facial Cleanser: “Penetrates deep down to keep your skin cleaner and clearer! Only cleanser in different formulas for dry and oily skins.”

‘Once a Day’ Deodorant Stick: “Keeps you fresh all day! Not a messy cream! Not a drippy spray. Safe for skin and fabrics.”

‘Once a Day’ Hair Spray: “Contains lanolin to keep your hair softer, plus ‘Hi-Sheen’ to keep it more radiant. Regular for firmer set and hard to manage hair. Super-Soft for loose casual, softer hair.”

The production of ‘dry’ and ‘oily’ forms for some products also enabled Hazel Bishop to provide rudimentary treatments for different skin types. Customers with dry skins were to use Dry Skin Cleanser, Liquid Make-up and then Compact Powder (for dry skins) whereas those with an oily skin used Oily Skin Cleanser, Liquid Make-up and then Compact Powder (for oily skins).

Budget brand

Spector’s marketing strategy was based on sales rather than margins. To maximise sales he had aimed Hazel Bishop at mass-market retailers like Woolworth’s rather than department stores, beauty salons or better class drug stores and he relied on television advertising to maintain sales. If sales diminish, money to engage in expensive television advertising becomes scarcer. However, if advertising is curtailed, sales decline and a vicious downward spiral develops. This is what happened to Hazel Bishop.

Some of the sales pressure on Hazel Bishop came from other budget brands like Art-Matic but the majors were also partly responsible. A number of these developed additional lines to cover the less expensive segments of the cosmetic market. This gave them a considerable advantage as they could leverage the cachet of their premium lines across all their products while cheaper brands like Hazel Bishop could only compete on price.

Above: 1954 Hazel Bishop trade advertising to boost sales.

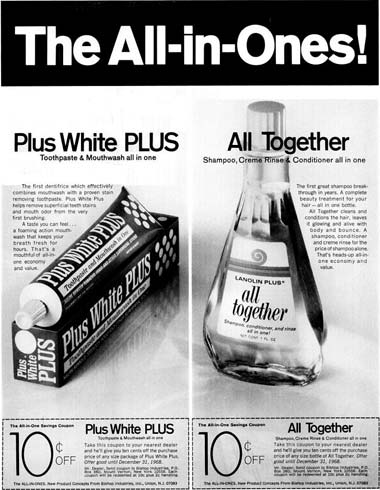

Hazel Bishop languished in this situation through mergers, buyouts and name changes. By the early 1980s, the company, by then called Bishop Industries, was known as a maker of low-priced cosmetics and for the hair and skin products added to the line when Hazel Bishop merged with Lanolin Plus in 1962.

Above: Bishop Industries factory.

Many tried to improve the fortunes of the brand but it fell into disuse and, as far as I can tell, there are no products on the market sold using the Hazel Bishop brand.

Hazel Bishop herself continues to be remembered although she is often incorrectly credited with inventing indelible lipsticks.

See also: Indelible Lipsticks

Timeline

| 1948 | Hazel Bishop and Alfred Berg form the Hazel Bishop Corporation. |

| 1949 | Hazel Bishop lipstick trialed in fashion show at Barnard College. |

| 1950 | Lasting Lipstick goes on sale in department stores. Raymond Spector joins the company. Television advertising begins. |

| 1951 | Bishop resigns as President of Hazel Bishop and begins lawsuit. |

| 1952 | New Products: Complexion Glow. |

| 1953 | Sales top US$10 million and Hazel Bishop gains 25% of the lipstick market. New Products: Long-Lasting Nail Enamel. |

| 1954 | Bishop settles her law suit against Hazel Bishop, sells out her remaining shares and leaves the company. Hazel Bishop becomes a public company. Hazel Bishop acquires a plant in Paramus, N.J. Hazel bishop lipsticks are reformulated. |

| 1955 | New Products: Compact Make-up; and Liquid Make-up. |

| 1956 | Spector reports to shareholders that the company made a loss in 1955. Hazel Bishop (Australia) Ltd. registered. New Products: Facial Cleanser (in dry and oily forms); and Once a Day Hair Spray. |

| 1957 | New Products: Formula 77 Lipstick. |

| 1958 | Controlling interest in Hazel Bishop stock acquired by C&C TV Corporation which then becomes Television Industries, Inc. New Products: Longer Lasting Hair Spray. |

| 1959 | New Products: Complete eye make-up line which includes mascara, eye shadow and eye pencil. |

| 1961 | Spector and a group of investors regain control of the Hazel Bishop Corporation. New Products: Creme ’n Powder liquid make-up. |

| 1962 | Hazel Bishop and Lanolin Plus merge to form Bishop Industries. New Products: Fresh ’n Bright cream rouge. |

| 1963 | New Products: Fantastic lipstick. |

| 1964 | New Products: Sudden Change, a wrinkle smoother. |

| 1965 | New Products: Brush ’n Blush powder rouge. |

| 1966 | Bishop Industries bought by a real estate investment company. |

| 1967 | Bishop Industries acquires Veri-Tone of Newark N.J., a private-label manufacturer of cosmetics. Bishop Industries acquires Beadmore, Inc. makers of bath products. |

| 1971 | Bishop Industries under Chapter XI sells plant, offices and real estate in New Jersey. Future manufacturing will be through private label makers. |

| 1975 | Bishop Industries bought by Morton Edell and becomes a division of Toiletry Products of America. |

| 1981 | Toiletry Products of America sold to Quadrillion, Inc. and becomes Bishop Industries again. Hazel Bishop cosmetics selling in stores again after several years of inactivity. |

| 1991 | Bishop Industries sold to an investment group led by Jack Rosen. Renamed Hazel Bishop International, Inc. |

First Posted: 31st May 2010

Last Update: 4th November 2022

Sources

Appell, L. (1982). Cosmetics, fragrances and flavors: Their formulation and preparation with an introduction to the physical aspects of odor and selected syntheses of aromatic chemicals. Whiting, NJ: Novox.

Archer, A. (1957). Your power as a woman: How to develop and use it. New York: Hazel Bishop, Inc.

Broadcasting telecasting: The newsweekly of radio and television. Washington, DC: Broadcasting Publications, Inc.

deNavarre, M. G. (1975). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd. ed., Vol. IV). Orlando: Continental Press.

Drachman, V. G. (2002). Enterprising women: 250 years of American business. Boston, Mass: Vernon Press.

The drug and cosmetic industry. (1958). New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Fox, S. R. (1997). The mirror makers: A history of American advertising and its creators. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Perfumery and essential oil record. (1954). London: G. Street & Co., Ltd.

Television magazine. New York: Frederick Kugel Company, Inc.

Tobias, A. (1976). Fire and Ice: The story of Charles Revson—the man who built the Revlon empire. New York: William Morrow.

Ware, S. (Ed.) (2004). Notable American women: A biographical dictionary. USA: Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

1951 Hazel Gladys Bishop [1906-1998] testing a batch of lipsticks.

1950 Hazel Bishop Lasting Lipstick. The tag ‘It stays on you, not on him’ was created by the ad division of Hecht Brothers department store in Washington. Raymond Spector added the more enticing photo of the kissing couple (R. Bishop, personal communication, March 2012).

Israel Raymond Spector [1904-1984]. In 1930s, he had achieved a degree of fame in the advertising industry by turning the radio hero, The Lone Ranger, into a money-making enterprise.

1951 Hazel Bishop No-Smear Lipstick. Actually the no-smear required a bit of work. “To make sure your Hazel Bishop Lipstick will not smear off, blot with tissue until no more red lip-prints come off.”

1952 Hazel Bishop No-Smear Lipstick.

1952 Hazel Bishop.

1952 Hazel Bishop Complexion Glow liquid-creme rouge.

1956 Hazel Bishop Ultra-Matic Lipstick Case.

1957 Hazel Bishop products.

1957 Hazel Bishop ‘Once-a-Day’ Cosmetics.

1957 Hazel Bishop Formula 77 Lipstick. This ‘hypo-allergenic’ creamy lipstick was not blotted but rather was applied as heavily as the consumer wished.

1957 Hazel Bishop products on sale.

1958 Hazel Bishop Perfume Stick.

1958 Hazel Bishop Ultra-Matic compact make-up.

1959 Hazel Bishop cosmetics. The products shown are Ultra-Matic Lipstick, 7-Day Nail Polish, Ultra-Matic Compact Make-up, Liquid Cream Make-up, Eye Make-up (mascara, eye pencil and eye shadow).

Hazel Bishop longer lasting cosmetics.

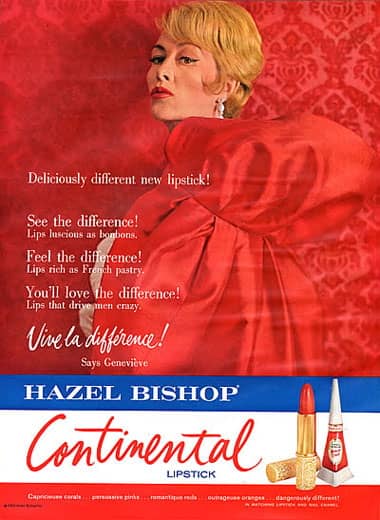

1962 Hazel Bishop Continental Lipstick and matching nail enamel.

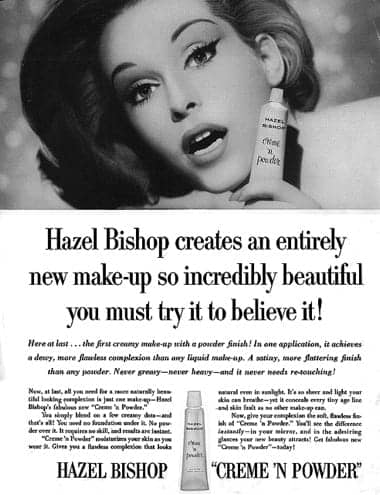

1962 Hazel Bishop Creme ’N Powder in 17 shades.

1962 Hazel Bishop Fantastick Long Length Lipstick and matching nail enamel.

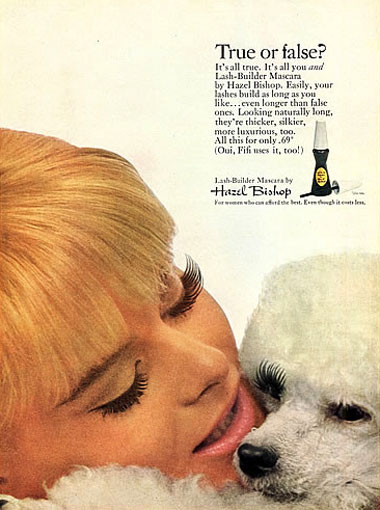

1964 Hazel Bishop Lash Builder Mascara.

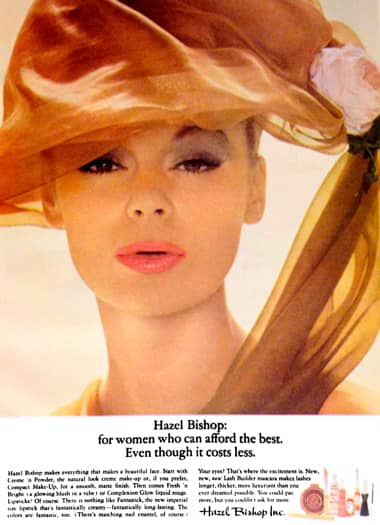

1964 Hazel Bishop.

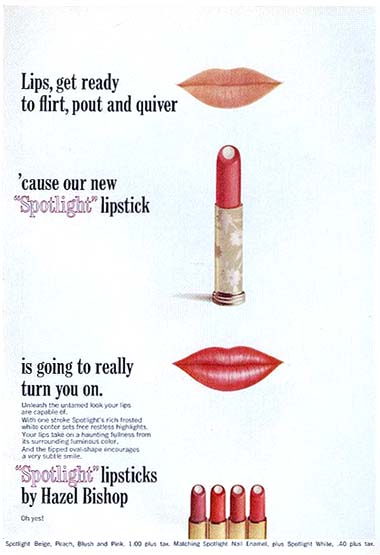

1965 Hazel Bishop Spotlight Lipstick in Beige, Peach, Blush and Pink shades, an idea later used in Max Factor’s Ultralucent Cream Center Lipsticks (1969).

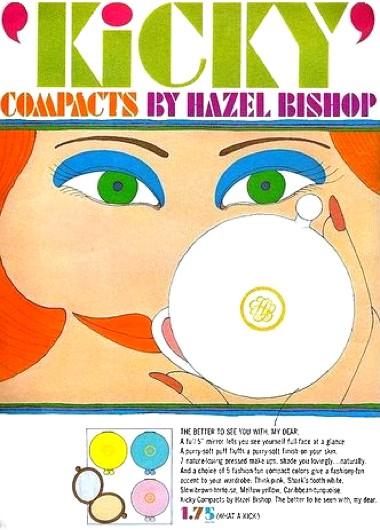

1965 Hazel Bishop Kicky Compacts.

1965 Hazel Bishop Lighter-Than-Air make-up.

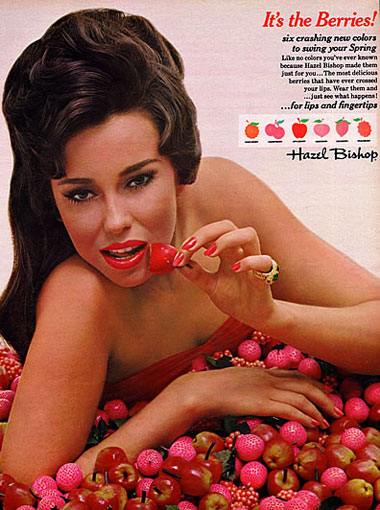

1965 Hazel Bishop Lipstick in berry colours.

1966 Hazel Bishop range discounted at Peoples Drug Stores. Products include Human Hair Lashes, Shade ’n Shadow Kit, Lash-building Mascara, Nail Enamel, Compact, Lipstick, Liquid Make-up, Quick Touch Make-up, Eye Pencil, Cake Eyeliner Kit.

1967 Hazel Bishop cosmetics. Products shown are Brush ’n Blush, Long Wearing Nail Enamel, Lash-Building Mascara, Lipstick (in 8 fashion shades), Creamy Liquid Make-up, Insignia Compacts, Brush Brow ’n Liner, Human Hair Lashes and a Kit of 5 Cream Eye Shadows.

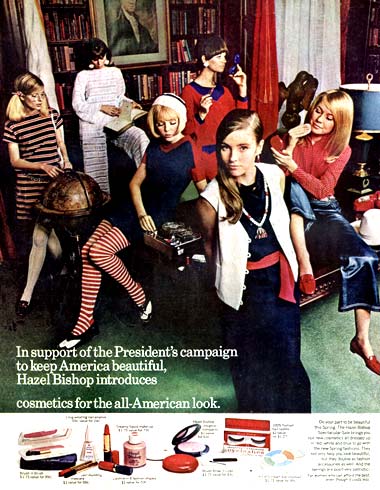

1968 Bishop Industries. Some of the additional products acquired after the merger between Hazel Bishop and Lanolin Plus in 1961.