Colgate

Continued onto: Colgate-Palmolive-Peet

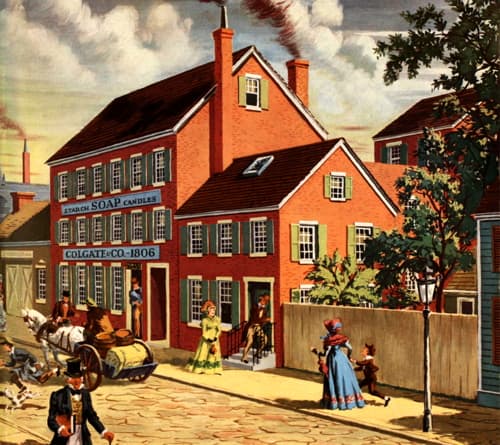

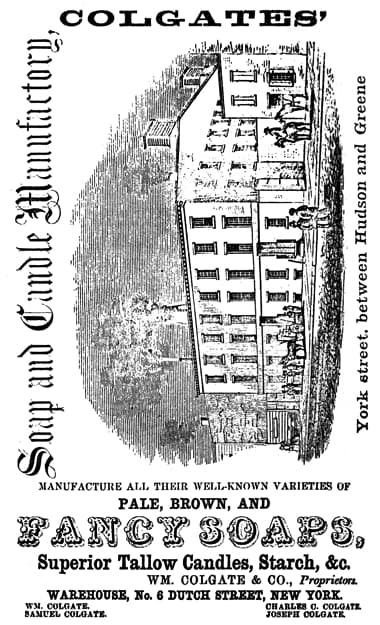

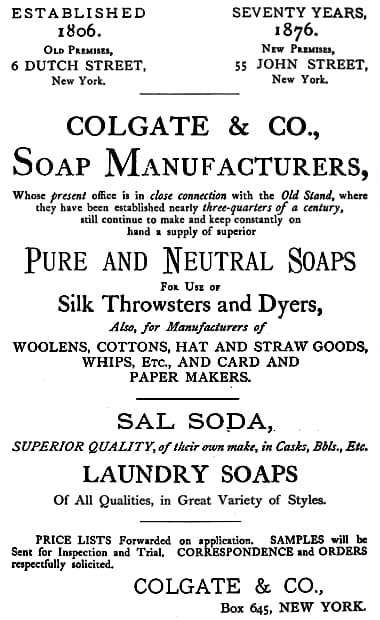

In 1806, William Colgate opened a business at 6 Dutch Street, New York. A number of sources say it was making starch, soap and candles but Colgate did not get into the starch business until the 1820s. Most likely, he was manufacturing laundry soaps and candles, trades he learnt from John Slidell & Company at 50 Broadway after joining them in 1804.

Above: An idealised version of the Colgate business in Dutch Street.

Above: Dutch Street after Colgate moved its offices to New Jersey in 1910. A number of buildings have been demolished. The layout of the remaining building differs from the drawing above.

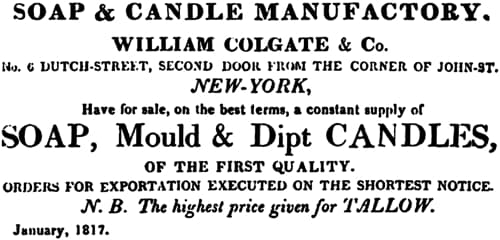

In 1807, Colgate went into partnership with Francis Smith and the firm then became Smith and Colgate. After buying Smith out in 1813, Colgate then partnered with his brother, Bowles Colgate [1789-1845] from 1813 to 1844, with the business now named William Colgate & Company.

Above: 1817 First Colgate advertisement.

Bowles Colgate’s son, Charles Carrol Colgate [1822-1880] and William Colgate’s son, Samuel Colgate, also became partners in the business and the firm was reorganised as Colgate & Company in 1858 after William Colgate’s death.

Dutch Street runs between John and Fulton streets in New York and Colgate gradually expanded its operations across this small block.

Above: 1905 Colgate wagon at Pier 13 in Lower Manhatten (Scorpy).

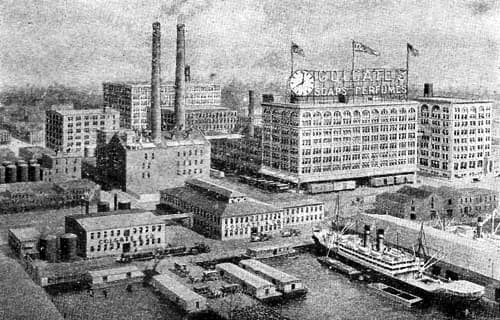

In 1847, with more space needed, the soap-making plant was moved to New Jersey. The Jersey City plant was extended over the years, a research laboratory added in 1896, with all of Colgate’s operations moved there by 1910, except for a showroom maintained at 199 Fulton Street.

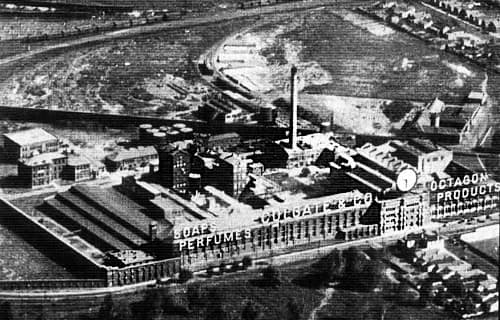

Above: 1879 Colgate Factory in New Jersey. The different building styles reflect new additions completed over time.

Above: 1909 Colgate Factory in New Jersey showing further additions and modifications

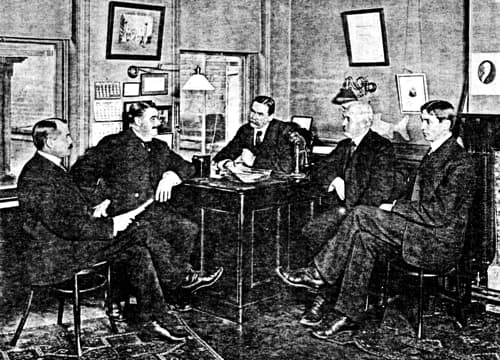

In the 1860s, younger members of the extended Colgate family began joining the firm. In 1867, Bowles Colgate II, the son of Charles Carroll Colgate was made a partner and, between 1880 and 1906, five of Samuel Colgate’s six sons became partners as well, the other son, Samuel [1868-1902], becoming a Baptist minister. This started with Richard Morse Colgate in 1880 and continued with Gilbert, Austen and Sidney, through to Russell Colgate in 1906. Following Samuel Colgate’s death in 1897, these sons took over management of the firm after their cousin, Bowles Colgate II, left in 1901, incorporating the business in 1908.

Above: 1906 Office of Richard M. Colgate at 55 John Street, New York.

Left to Right: Sidney Morse Colgate [1862-1930], Austen Colgate [1863-1927], Richard M. Colgate [1854-1919], Gilbert Colgate [1858-1933], and Russell Colgate [1873-1941].

After Colgate incorporated, Richard Morse Colgate became the company president. During his term, Colgate established its first international subsidiary in Canada, opening a factory at 8 St Helens Street, Montreal in 1918.

In 1919, after Richard Morse Colgate’s death, the presidency passed to Gilbert Colgate who had been serving as vice-president up to then. With the company still growing and in need of more manufacturing space, Colgate bought the Indiana Reformatory in Jeffersonville for about US$351,000 with the idea of setting up a new plant to service the Midwest. Ownership of the building did not begin until 1923 after which remodelling began, with production beginning in 1924 after the last prisoners were removed. A feature of the repurposed building was the installation of the Colgate clock which was moved from New Jersey.

Above: c.1917 Colgate New Jersey. The clock was replaced with a larger version after this one was moved to Jeffersonville in 1924.

Above: c.1929 Colgate Jeffersonville after the reformatory was repurposed and the New Jersey clock was installed.

Product diversification

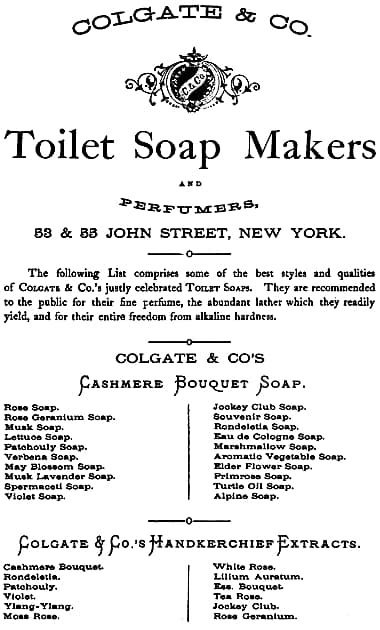

After Colgate got out of the starch business in 1866, a decision was made to expand the company’s perfume and fragrance ranges. Colgate was already making a number of Fancy Soaps but now began adding a wide range of fragrant toilet soaps along with perfume extracts and associated products such as talcum powders.

In 1873, in addition to distributing its own products across the United States, Colgate agreed to carry Chesebrough’s Vaseline products and continued to do so until Chesebrough merged with the Pond’s Extract Company in 1955.

See also: Chesebrough Manufacturing Company

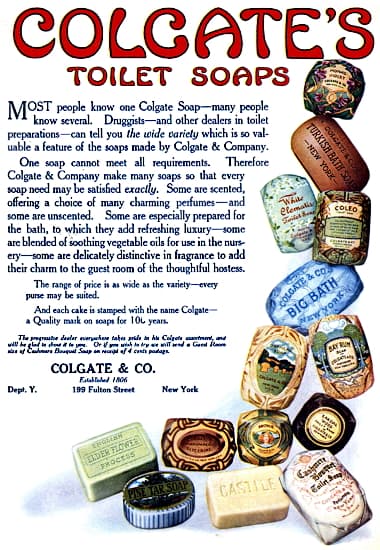

By 1886, Colgate was making over 100 different varieties of toilet soap including Cashmere Bouquet, a product destined to become a company staple.

Cashmere Bouquet

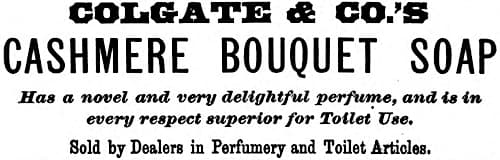

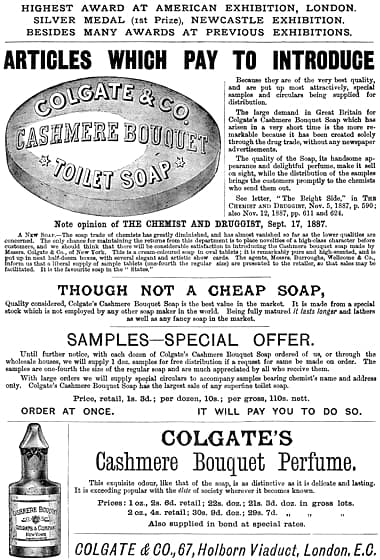

Colgate developed Cashmere Bouquet Soap in 1869, began advertising it in 1870, and trademarked the name in 1872.

1870 Cashmere Bouquet Soap. Each cake of Cashmere Bouquet was individually wrapped and sealed with sealing wax.

The fragrance used in the soap contained 12 flower oils including verbena, mignonette and lavender. The development of the scent often attributed to William P. Ungerer but this was not possible as the soap was created before Ungerer began working for Colgate. Soap and Chemical Specialties credit Frederich Augustus Guild [1831-1909] with the fragrance although they are mistaken in the date of its development.

Guild was always seeking new fragrances and blending materials collected for him. Early in 1870, he hit upon a combination that appealed to him as a possibility for a toilet soap. With the aid of an iron mortar and pestle, he pounded together his experimental perfume with a fine toilet soap base. Others in the company shared his enthusiasm over this new blend and agreed to market it under a new name—“Cashmere Bouquet.”

(Soap and Chemical Specialties, 1951, pp. 46, 215)

Cashmere Bouquet was an almost instant success and the scent proved so popular that Colgate added Cashmere Bouquet Handkerchief Extract in 1872. W. P. Ungerer worked for Colgate between 1872 and 1893 so he may have played a role in the development of the extract.

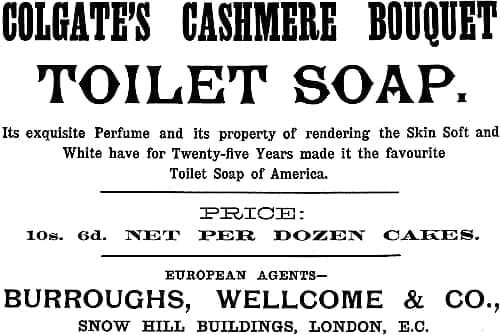

The popularity of Cashmere Bouquet Soap helped extend Colgate internationally and it became widely available around the world in the 1880s through local distributors, becoming available in Australia by 1888 at the latest. In Britain and Europe, Colgate products were distributed by Burroughs Wellcome after an agreement was reached between the two companies in 1886.

Above: 1886 Burroughs Wellcome European agents for Colgate.

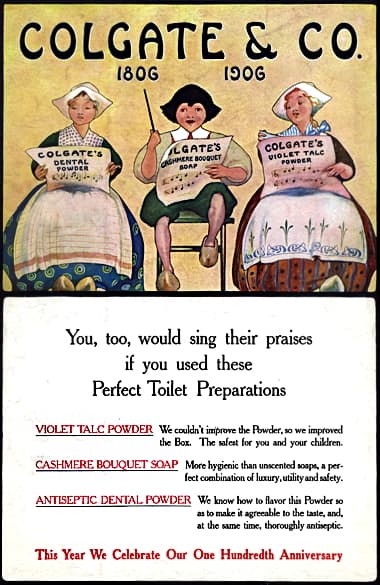

Centennial

In 1906, the company celebrated its centennial, hosting a large dinner for about one thousand employees at the Grand Central Palace in New York.

Above: 1906 Colgate Centennial Dinner.

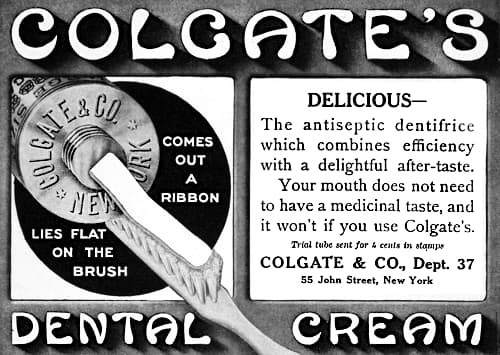

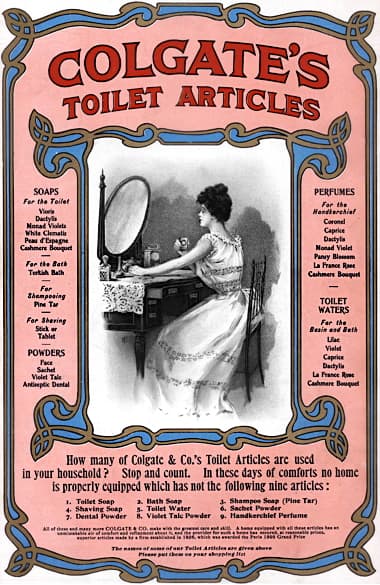

By now, Colgate was making over 3,000 different products including soaps, perfumes, toilet waters, shampoos, shaving sticks, face powders, talcs, dental powders and dental creams. Most of these are of little interest to me but, considering the importance of toothpaste to the long term history of the firm, I make special mention of Colgate Dental Cream (1877) and Colgate Ribbon Dental Cream (1904).

Above: 1909 Colgate Dental Cream.

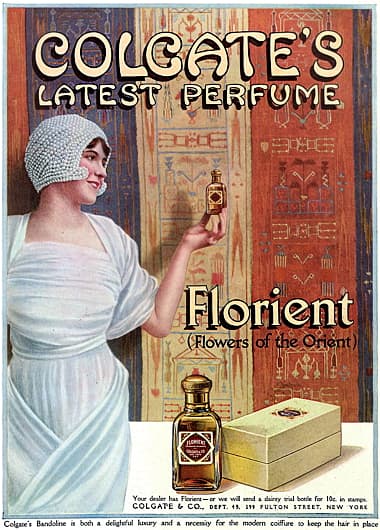

Although toiletries, such as toothpastes, shaving products and shampoos, would become the mainstays of Colgate’s general consumer business, fragrances – sold as perfumes, toilet waters, soaps and talcum powders – continued to be important to the firm until the 1920s by which time the use of toilet waters and talcum powders were becoming less fashionable and Colgate perfumes were suffering from increased competition from French imports.

Above: 1924 Manufacturing fragrant lines in the Colgate factory in New Jersey.

In 1914, when supplies of French products were restricted due to the First World War, Colgate tried to convince American women that its perfumes were as good as French imports. It began advertising the results of the ‘Colgate Perfume Test’ which ‘proved’ sophisticated women could not tell the difference between Colgate and foreign perfumes.

Above: 1917 Colgate Perfume Test.

However, the ‘Colgate Perfume Test’ seems to have had little influence in the long term and American women resumed buying French perfumes once supplies were restored.

Skin-care

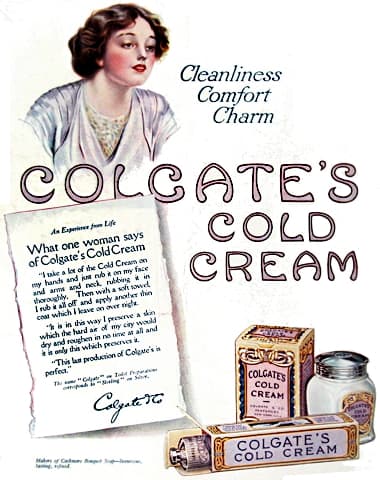

In the 1880s, Colgate began added skin-care cosmetics, starting with Colgate Cosmetic Glycerine Lotion and Colgate Cold Cream.

Cosmetic Glycerine Lotion: “[C]ools sunburn, and removes tan and freckles if correctly applied.”

Cold Cream: “[D]aily use softens the skin and preserves or restores the smooth texture which Nature intends and which helps to a beautiful complexion.”

Also see: Glycerine Creams and Jellies and Cold Creams

Beauty Culturists of the time thought that skin cleansing was the basis for a flawless complexion but there was considerable disagreement over whether soap and water or cold cream was the best cleanser.

See also: Soap and water

As a soap company, Colgate recommended using soap and cold cream in tandem, with the cold cream acting as an additional cleanser, massage cream and oil supplement. Colgate’s rationalisation for this approach used common understandings of the period that concentrated on clearing the skin pores.

Colgate’s Cold Cream gently massaged into the skin softens or dissolves the accumulations in the pores and frees these necessary little outlets. Result—a skin as fair and fresh as Nature meant and often better health.

So much for the pores—now, let us see about the need of the skin for oil. This need should be self evident—the skin secretes oil itself. The sebaceous glands—those tiny bodies which secrete this oil—should need no help. But poor, cheap soap, the dust and grime of the city, the overheated, drying air of modern houses and the too indolent indoor life of many women— all combine to offset the work of these oil-making glands. Without some help the skin becomes too dry and loses the beautiful suppleness and the satiny smoothness which it should and may have.

Colgate’s Cold Cream supplies this needed oil in an ideal form which makes up for any natural deficiency. By reason of its eminent suitability and the fact that it can be applied whenever needed a dry, parched skin may be avoided. (It will not produce or stimulate the growth of hair.)(Colgate advertisement, 1913)

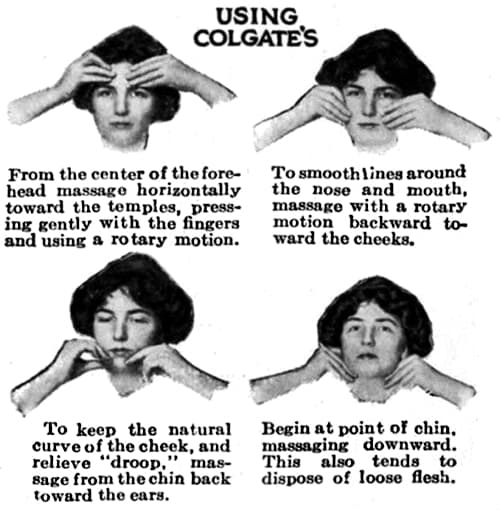

Massage was an important part of this process and Colgate provided some advice on how best to do this.

Above: 1913 Massage movements with Colgate Cold Cream.

By 1915, Colgate had rebadged its cold cream as Charmis Cold Cream using its Charmis fragrance introduced in 1904. In 1915, the company also introduced Colgate Mirage Cream, a type of vanishing cream. Colgate then combined these two cream to create a rudimentary skin-care routine – Mirage (Vanishing) Cream for the day and Charmis Cold Cream at night, an idea similar to that promoted earlier by Pond’s.

Mirage Cream: “Vanishing Cream for daytime use to prevent shine and as a perfect base for powder.”

Charmis Cold Cream: “[T]o be used at night to help keep your skin soft and clear.”

See also: Vanishing Creams, Day and Night Creams and Pond’s Extract Company

Make-up

By 1903, Colgate was selling face powders in a range of fragrances. After adding Mirage Cream as a powder base the company began to take its face powders more seriously, even though they were only available in White, Flesh and Rachel (Brunette) shades. In 1921, Colgate began adding a range of face powder compacts in mahogany or gold-toned cases some of which also contained rouge. These were used in a number Colgate Vanity Combinations which also included rouges and lipsticks.

Colgate’s interest in improving this area of its business may have been the reason behind its 1927 purchase of the Pompeian Manufacturing Company with its extensive range of skin-care and make-up cosmetics.

See also: Pompeian Manufacturing Company

Merger

In 1925, Gilbert became the company Chairman and the presidency was taken over by Sidney Morse Colgate. The growth the company had experienced up until now was starting to flatten out as competition increased.

Colgate’s low margins also needed attention. In 1927, Colgate sold about US$42 million worth of soaps and other lines but only made a net profit of $US2.4 million (Fortune, 1936, p.124). Profits from its laundry and toilet soaps far exceeded those from other areas of its business but this was due to their large volume of sales which were under heavy competition from larger companies such as Lever Brothers and Procter & Gamble.

In 1928, the Colgate board decided to accept the offer of a merger with Palmolive-Peet. Palmolive-Peet was a relatively young company but was larger than Colgate. Its sales were about US$51 million annually with net profits of about US$5 million so it also had a higher earnings-to-profit ratio than Colgate. The merger produced a company with assets of over US$63 million with total sales of about US$100 million (Fortune, 1936, p.124).

Also see: Palmolive

After the merger, the Colgate brothers allowed Charles Sumner Pearce [1877-1965], the president of Palmolive-Peet to become the president of the new company. The Colgate brothers were getting old – Gilbert Colgate was seventy and Sidney Colgate was sixty-six – and their business approach was very conservative. Pearce was younger, his approach to business dynamic and expansive. Unfortunately, Pearce’s plans for the company and his career were derailed by the stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression of the 1930s.

Timeline

| 1806 | William Colgate establishes a business at 6 Dutch Street, New York. |

| 1807 | William Colgate partners with Francis Smith and the firm becomes Smith & Colgate |

| 1813 | Smith & Colgate becomes William Colgate & Co. |

| 1847 | Manufacturing moved from New York to New Jersey. |

| 1858 | Colgate reorganised as Colgate & Company. |

| 1866 | Perfumed soap and perfumes/essences introduced. |

| 1869 | New Products: Cashmere Bouquet Soap. |

| 1872 | New Products: Cashmere Bouquet Handkerchief Extract. |

| 1873 | Colgate agrees to distribute Vaseline products. New Products: Dental Powder. |

| 1896 | Research laboratory established. |

| 1904 | New Products: Ribbon Dental Cream. |

| 1908 | Colgate incorporates. |

| 1910 | Company moves to Jersey City. Showroom retained at Fulton Street. |

| 1914 | Colgate & Co. Ltd. established in Montreal, Canada. |

| 1915 | New Products: Mirage Cream. |

| 1917 | New Products: Lather Shave Cream. |

| 1918 | Factory opened in Montreal. |

| 1921 | Indiana Reformatory buildings sold to Colgate. |

| 1927 | Pompeian Manufacturing Company bought. |

| 1928 | Colgate merges with Palmolive-Peet. |

Continued onto: Colgate-Palmolive-Peet

First Posted: 29th December 2020

Last Update: 14th April 2023

Sources

The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review. (1906-1955). New York: Robbins Perfumer Co. [etc.].

Cashmere Bouquet. (1951). Soap and Chemical Specialities, May, 45-46, 215.

Colgate-Palmolive-Peet. (1936). Fortune, XIII(4). 120-125, 138, 142-142, 148.

Colgate, S. M. (1924). A policy that guided 118 years of steady growth. System: The Magazine of Business, December, 717-720, 783-785.

Hardin, S. T. (1959). The Colgate story. New York: Vantage Press, Inc.

Haynes, W. (1948). American chemical industry: The merger era (Vol. IV). New York: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc.

Muirheid, W. G. (1910). Jersey City of to-day: Its history, people, trades, commerce, institutions & industries. Jersey City, NJ.

Updegraff, R. R. (1921). The story of Colgate & Co. Printers’ Ink Monthly, 3(2), July, 13-14, 63-64.

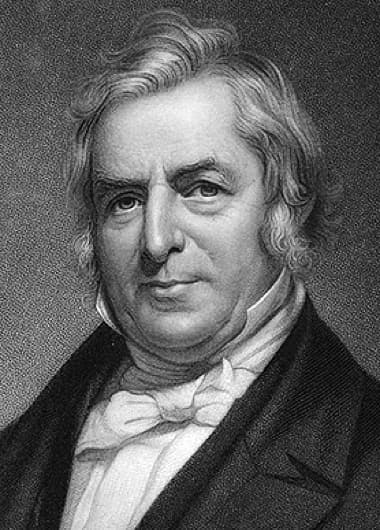

William Colgate [1783-1857]

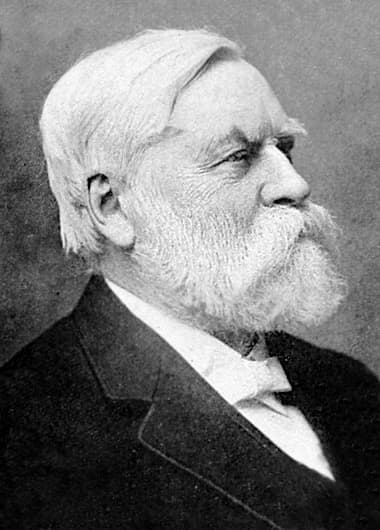

Samuel Colgate [1822-1897]

1854 Colgate Pale, Brown and Fancy Soaps, Tallow Candles and Starch.

1872 Colgate Toilet Soaps and Handkerchief Extracts.

1876 Colgate & Co. trade advertisement.

1888 Trade advertisement for Colgate Cashmere Bouquet (London).

1891 Colgate Cold Cream.

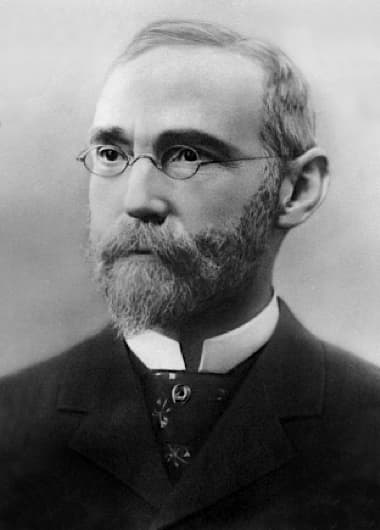

Martin Hill Ittner [1870-1945]. He joined Colgate as its chief chemist in 1896, established its research laboratory and became the company’s director of research until his death in 1945.

1901 Colgate & Co.

1902 Colgate Toilet Articles.

1903 Colgate.

William Philip Ungerer [1833-1907], the chief perfumer for Colgate between 1872 and 1893.

1906 Colgate centennial.

1912 Colgate Toilet Soaps.

1914 Colgate Cold Cream.

1914 Colgate Florient Perfume.

1915 Colgate Charmis Cold Cream.

1920 Colgate Mirage Vanishing Cream and Charmis Cold Cream.

1922 Colgate Cashmere Bouquet Face and Talcum Powder.

1922 Colgate Gold Compact.

1923 Colgate Diamond Compact.

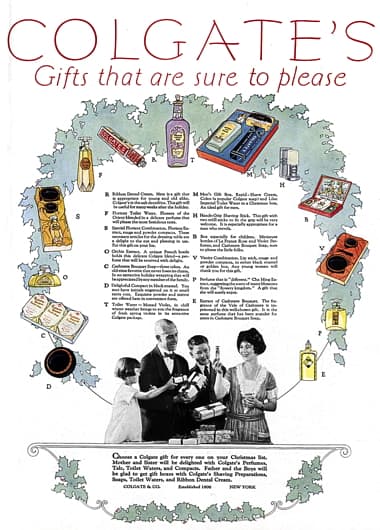

1923 Colgate Christmas suggestions.

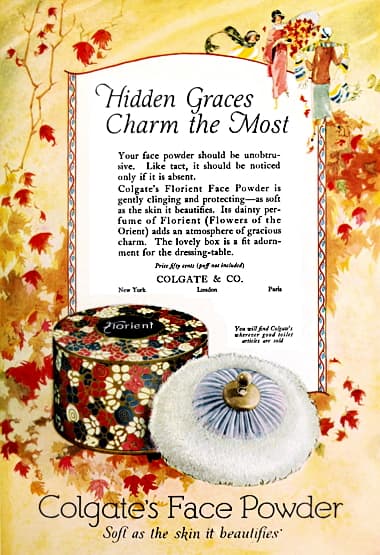

1924 Colgate Florient Face Powder.

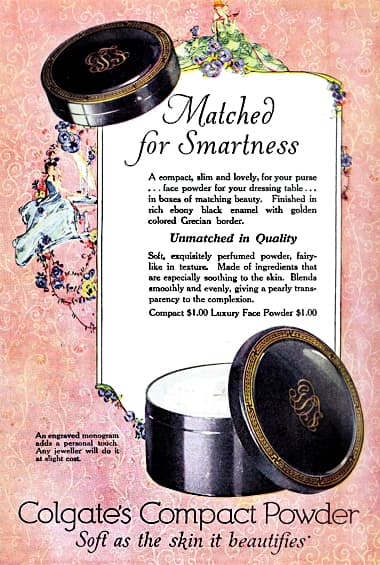

1924 Colgate Compact Powder.