Max Factor

Continue to: Max Factor (1930-1945)

No cosmetic firm is more closely tied to the development of the movie industry in Hollywood than Max Factor. This tight connection might explain why descriptions of the early life of Maksymilian Faktorowicz, a.k.a Max Factor, read more like a film script than real life. Most of these stories originate with Fred E. Basten [b.1930] who did public relations work for Max Factor in Hollywood and wrote two books about him but his recollections are not always trustworthy.

Briefly summarised, Basten starts by outlining Max Factor’s humble origins in Lodz, Poland, his five years of military service in the Russian army, and his subsequent opening of a small shop in Ryazan, a city about 200 km from Moscow.

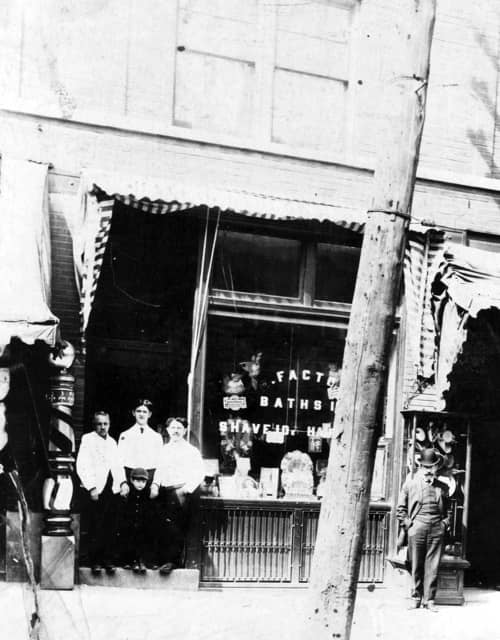

Above: Maximilian Faktorowicz in front of a hairdressing shop (Basten, 1995). The large sign reads ‘barber’s, hairdresser’s or wigmaker’s shop’ while the one above the doorway says ‘Entrance to Barber’s etc’. The building still stands today.

Continuing on, Basten recounts how a passing theatrical troupe buying make-up from his shop led to Max being employed by the Imperial Russian Grand Opera in the court of Czar Nicholas II [1868-1918]. He then describes how court restrictions required Max to keep his marriage and three children a secret, the family’s escape from Russia, to Hamburg from where they made their way to America on the S.S. Moltke, arriving there in February, 1904.

Basten states that Max landed in American with the equivalent of nearly US$40,000 in savings but was swindled of most of his money and stock by a business partner during the Louisiana Purchase Exposition – also known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. Now, considerably poorer, Max went back to his original trade and opened a barber shop at 1513 Biddle Street, St. Louis.

Above: 1906 The Factor barber shop in St. Louis providing baths, shaves and haircuts. Unknown barber (left), Davis Factor (centre) and Max Factor (right).

An alternative but perhaps more creditable version of Max Factor’s early life might be gained from looking at the manifest of the S.S. Moltke. According to this, the Factor family travelled to the United States in steerage and Max had only US$400 in his possession when he arrived, not US$40,000. This suggests that Max led a relatively simple existence in the Russian Empire as a hairdresser, barber and wigmaker, moved to America to escape Jewish persecution in Russia, arrived in the United States without fame or fortune, and then worked his way up.

I have also been unable to find any record of Max Factor being at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition which suggests that the swindle story was concocted to explain why Max lacked the means to establish a more impressive business when he settled in St. Louis.

Los Angeles

Another story that looks scripted is that Max moved to Los Angeles in 1908 to become part of the motion picture industry. This also lacks credibility. New York and Chicago were the motion picture capitals of America at the time with Los Angeles being, a temporary base used by studios to film during the winter months at best. It would not be until 1911 that the first Hollywood production company, the Nestor Film Company, would open for business there.

Max may have relocated to Los Angeles for a number of reasons. He may have been trying to escape the notoriety of his second wife deserting him and was perhaps looking for a fresh start after getting married again. He might also have been attracted to Los Angeles by the discovery of the Californian oil fields which drew men to the state; men who would be in need of a good barber and perhaps the occasional toupee.

Whatever the impetus, by January, 1909, three months after arriving in Los Angeles, Max had founded Max Factor & Company and set up his barber shop, the Antiseptic Hair Store at 1204 South Central Avenue.

Hollywood

As luck would have it, 1908 – the year Max Factor arrived in Los Angeles – was an important date in the history of the movie industry in the United States. In that year, Thomas Edison set up the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC), also known as the Edison Trust. Based in New Jersey, it combined most of the major film companies and leading film distributors along with Eastman Kodak, the largest American supplier of film stock at the time.

The trust was designed to protect Edison’s patents and exert control over the developing American motion picture industry. A number of independent filmmakers reacted to the formation of the trust by moving west where it was more difficult for MPPC detectives and their agents to operate. Good year-round weather and a wide range of shooting locations helped cement a movie industry in California so, even after the MPPC patents expired in 1913, the movie industry in the west continued to grow. By 1915, Hollywood was a major film production centre and it produced most of films made in the United States by the 1920s.

Hair goods

The Los Angeles City Directories have Max Factor listed as ‘Barber’ at 1204 South Central Avenue between 1910 and 1912 but it also lists him as ‘Hair Goods’ at 1210 South Central in 1912 while continuing as a barber at a new address at 1223 South Central.

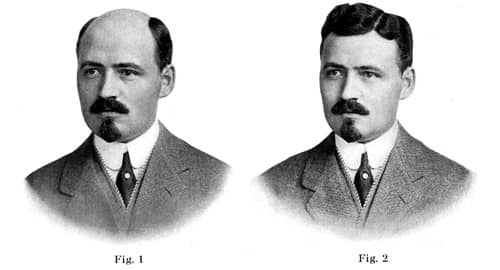

By 1913, Max appears to have closed the barber shop in South Central and is only listed as selling hair goods. A company brochure from 1917 – containing pages of ‘before’ and ‘after’ photographs – shows that the business was making a range of wigs, switches and toupees for men using hair imported from Europe.

Above: 1917 Before and after photographs from a Max Factor company brochure.

Also see the company booklet: Max Factor and Company, recognized leader in the production of artistic toupees and wigs. (1917)

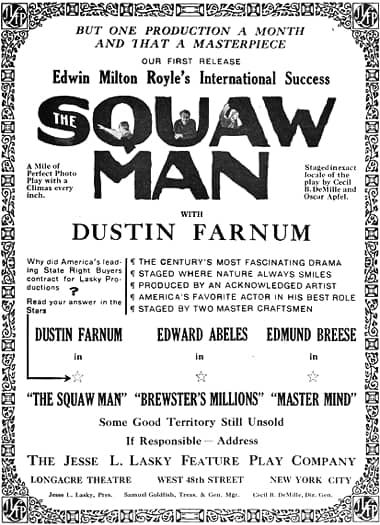

Basten writes that it was wigs that first got Max Factor involved with the movie business in California in a major way when, in 1913, Cecile B. DeMille rented a number of Max Factor wigs for his feature film ‘The Squaw Man’ (Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company, 1914).

South Hill Street

As his business expanded, Max moved around Los Angeles searching for a good location for his business. The Los Angeles City Directories indicate that he had relocated to the Pantages Building at 536 South Broadway by 1915 – initially to the fifth and then to fourth floor – before settling at 326 South Hill Street in 1916.

There are a number of photographs taken of the shop in South Hill Street which indicate that hair goods – such as hair pieces, dyes, shampoos, brushes and combs – were the most common stocked items but that make-up products also took up some counter space.

Above: South Hill Street with two unknown individuals. Hair occupies the front cabinet but the one next to it appears to contain make-up.

Above: Back counter of South Hill Street with Cecelia (left) and Freda Factor (right). Neither woman is wearing a wedding ring so this was probably taken before 1923.

Above: Back of South Hill Street with Freda Factor (right) and an unknown woman.

Above: c.1920 South Hill Street Store with Max (left) and Davis Factor (centre). There is a Pompeian Fragrance advertising stand in the back of the shops that dates from 1919. Hair pieces occupy the cabinets to the left at the front of the store.

Above: c.1924 Interior of South Hill Street with Max (left), Frank (centre) and Davis Factor (right). There is a Mineralava advertising stand in the back of the shop that dates from 1924. The Los Angeles City Directories also first list Frank and Davis working as clerks in the business in 1924.

Supreme greasepaint

Basten writes that Max Factor stocked stage make-up from firms like Leichner and Steins but also sold his own Supreme brand products which included henna shampoo, liquid white, rouge, face powder, eye make-up, cleansing cream and lip rouge along with a range of a accessories such as a face powder brush (Basten, 2008, p. 22).

Above: 1927 Max Factor and Mabel Normand [1892-193] during the filming of ‘Anything once!’ (Hal Roach Studios). Mabel is using a Max Factor Powder Brush that Basten says he first developed in 1921.

According to Basten, Max Factor added greasepaint to the Supreme range in 1914. The greasepaint, which was a cream rather than a stick, was made by mixing pigments into a base of vegetable oils. Described as a ‘flexible greasepaint’, it was supposedly developed to overcome the problems associated with the use of stick greasepaint in motion pictures.

As more movie people visited Max’s store, he learned that they needed something different from stage make-up, which was much too heavy. Stage make-up had to be applied one-eighth of an inch thick, then powdered. When it dried it formed a stiff mask and often cracked, which wasn’t a problem in the theater where audiences were seated far away from the performers, but onscreen, especially in close-ups, it didn’t work. Even hairline cracks were visible. What actors needed was a make-up that allowed them to show expression without cracking and something with enough tints to give them a natural look, not a mask.

(Basten, 2008, p. 23)

Basten claims that Max Factor developed this flexible greasepaint in 1914, but Max Factor wrote that the product was first introduced to the movie industry in 1923, some nine years later.

It was in nineteen twenty-three (1923) that I was able to present to the profession the first flexible make-up that could be applied on the skin very thin, and yet retain all the covering and coloring qualities necessary. I must admit that it was far from perfect but it was the first and only step ever made to accurately improve theatrical make-up to that time.

(Factor, 1928, p. 8)

A report in the L.A. Times in 1925 also suggests that the flexible greasepaint was first manufactured in the 1920s.

Discovery of a thin flexible make-up by Angeleno, Max Factor is revolutionizing the preparation of faces for the screen and stage and bides fair to make Los Angeles the cosmetic manufacturing center of the world.

Because of this discovery, which is expected to create demands for it in all parts of the world, Factor is now negotiating for the purchase of a plant in which he can produce the article on a tremendous scale and also others of a similar line he has perfected.

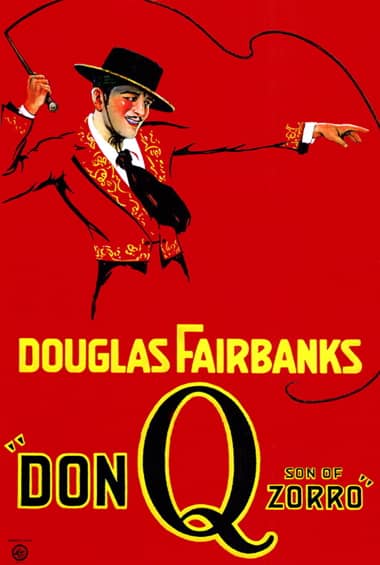

The flexible make-up is now undergoing severe tests at the hands of Douglas Fairbanks and the company now playing with him in his new picture, and at the Famous-Players-Lasky studio in Hollywood. Tests have already shown that the article permits registration of all the face, a registration that heretofore has been confined chiefly to the eyes and mouth.(New form of make-up discovered. (1925, March 8). The Los Angeles Times, p. 63)

It is possible that both dates are correct. If another story from Basten is true, Max may have developed a cream greasepaint in 1914 for use by a few individual actors but only promoted it after he was snubbed by Leichner during his visit to their headquarters in Germany in 1922.

While Max and Jenny were in Germany, he decided to visit the offices of Leichner, which he had long represented in the United States. … When he introduced himself at the front desk, he expected to be greeted warmly. Instead he was told to sit and wait. Ignored for more than an hour, Max grew increasingly angry. He stormed out of Leichner, hurried back to his hotel, and cabled his sons. “Start selling greasepaint in tubes,“ it read.

(Basten, 2008, p. 46)

Cream greasepaint – also called cream-paint or flesh cream – was not a new idea. Similar products had been made by a number of make-up suppliers well before the First World War (Young, 1905) mainly for use by actresses. However, it was generally sold in pots so packaging it in tubes appears to have been an innovation. Max apparently thought it was more sanitary.

Above: 1928 Max Factor (back) point to a tube of Supreme Greasepaint, Alice Calhoun [1900-1966] (left), Vesta McDonald (center), and Ruth Dwyer [1898-1978] (right). The caption reads “A good back is a fine place for an artist to experiment with new colors—so when Max Factor, Hollywood make-up artist, invented some new shades, he tried them out on Miss Vesta McDonald’s back”. Max is pointing to his Supreme Greasepaint in a tube.

See also: Greasepaint and Early Movie Make-up

The ‘House of Make-up’

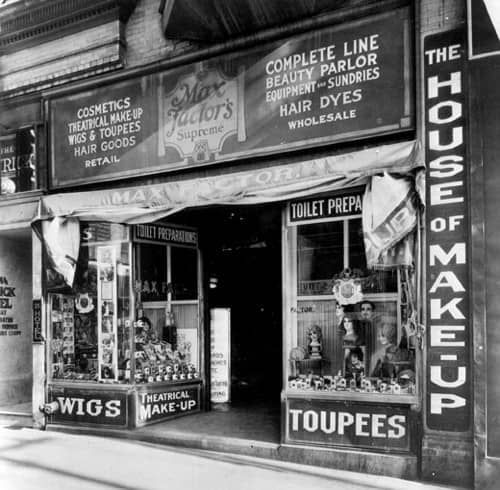

By the 1920s, Hollywood was taking make-up more seriously and the studios had begun to install make-up departments on their lots, staffed with specialist make-up artists. By 1922, Max Factor was describing his store at 326 South Hill Street as the ‘House of Make-up’ which suggests that supplying make-up to actors and film studios had became a major part of his business.

Above: c.1929 External view of the Max Factor store at 326 South Hill Street next to the Myrick Hotel. The windows are filled with Max Factor cosmetics, along with wigs and other hair pieces. Basten suggests this image was taken in 1920 but photographs displayed in the window are dated at 1928 so this image must have been taken just before or during the move to North Highland Avenue.

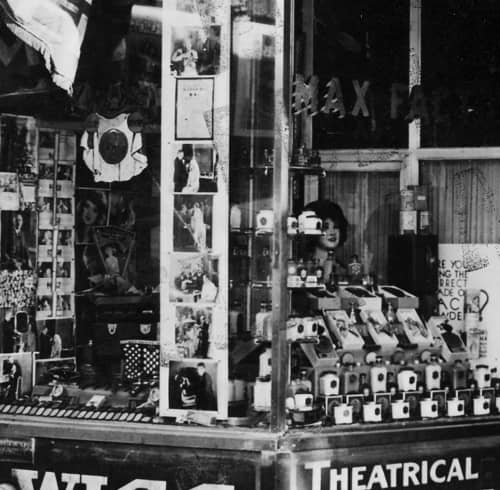

Above: c.1929 A closer view of the left shop window in the Max Factor store at 326 South Hill Street showing publicity photographs and a range of what appear to be Max Factor Society cosmetics.

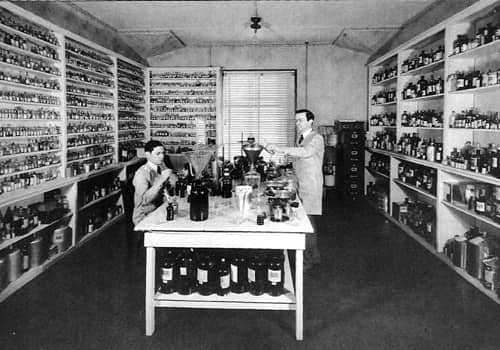

As well as providing make-up services to movie stars and studios, Max Factor also maintained a research laboratory. Frank Factor, Max Factor’s second son, appears to have worked in the laboratory but the company also had a chemist, Steve Frentzy, on its payroll by 1925.

Above: 1924 Frank Factor (left) and a chemist, possibly Steve Frentzy, in a well-stocked research laboratory.

Max Factor’s industry connections, his well-stocked laboratory, his experience in manufacturing make-up and, above all, his location in Hollywood, put him in a strong position to assist the film industry there when it adopted three new technologies in the second half of the 1920s: cheaper panchromatic film in 1926; sound in 1927; and Technicolor Process 3 film in 1928.

“Make-up is a dozen times more important to-day than it ever was,” he told me. “Three years ago the players were beautiful or handsome of feature, and got their jobs because of that. Some greasepaint, powder, lip-rouge and an eye pencil were enough make-up.

“Then the talkies came. The pretty boys and girls stammered, squeaked, and—experienced stage folk came along to take their places. They weren’t always beautiful—for instance, the dyed-in-the-business character people, and we had to beautify them, men and women. Others were beautiful, particularly as to coloring, for on the stage color harmony counted more than features. When color was added to pictures, it helped the stage players more than the picture people, but we had to start all over again with an entirely new type of make-up.”(Max Factor interviewed by MacCulloch, 1930, p. 88)

Two of these innovations – panchromatic and Technicolor film stocks – required the development of new types of professional make-up and Max Factor had the connections, technical expertise and production facilities to develop and manufacture them.

Make-up Studio

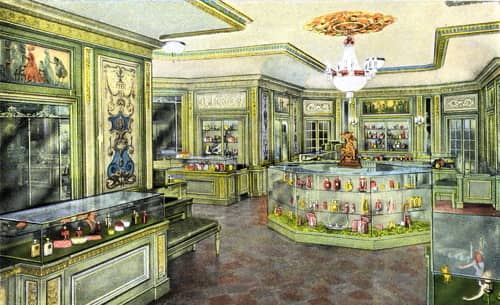

By 1925, Max Factor had leased additional capacity at 2453 Brooklyn Avenue (today’s Cesar Chavez Avenue). However, the business was soon in need of extra space and, in 1928, the company bought and began renovating the Hollywood Storage Company Building at 1666 North Highland Avenue. The remodelled building, which contained over 40,000 square feet of floor space, had its first (ground) floor devoted to offices, sales, a salon and lecture room while the remainder was used for manufacturing and packaging. The extra production space was sorely needed as Max Factor had released its Society line the previous year.

Above: Drawing of the showroom at North Highland Ave.

Above: 1928 Max Factor at the opening celebrations in the showroom at North Highland Ave.

Above: The make-up and hairdressing studio on North Highland Ave.

Society make-up

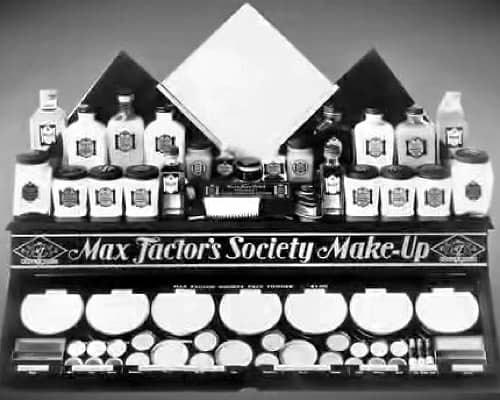

In 1927, the Max Factor company decided to capitalise on the growing acceptance of make-up and introduced its Society range. Created as a general cosmetic line it was advertised and sold nationally across the United States.

Above: Display stand for Max Factor Society Make-up.

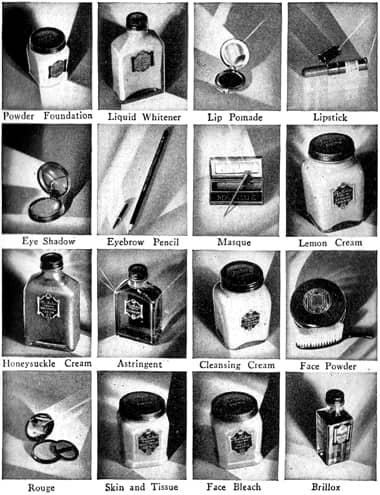

Leaving aside the sundries and manicure products, the range consisted primarily of make-up with a small number of skin creams used to prepare the skin for make-up.

1928 Product List (Society Make-Up, U.S.) included:

Make-up including Face Powder (Shades: White, Flesh, Rachelle, Natural, Brunette, Ochre, Olive, Evening, and Summer Tan); Rouge (Shades: No. 18, Flame, Blondeen, Carmine, Raspberry, Natural, and Day); Lipstick (Shades: Light, Medium, and Dark); Lip Pomade (Shades: Light, Medium, and Dark); Eye Shadow (Shades: Brown, Grey, and Blue); Dermatograph Pencil (Shades: Black, and Brown); Masque (Shades: Black, and Brown); Powder Foundation Cream (Shades: White, Pink, Rachelle, and Natural); Liquid Whitener (Shades: White, Pink, Rachelle, and Natural); and Make-Up Blender (Shades: Flesh, Rachelle, and Natural).

Skin care cosmetics including Skin and Tissue Cream, Honeysuckle Cream, Astringent Cleansing Cream, Cleansing Cream, Lemon Cream and Face Bleach; manicure cosmetics including Cuticle Cream, Cuticle Remover, Liquid Nail Enamel, Nail Polish, Nail White, Nail Tint and Nail Enamel Remover.

Assorted sundries including a Face Powder Brush and Brillox, a hair brilliantine.

There was nothing new here, a number of these items had been available in the earlier Supreme range and similar items had been placed on the American market by other producers years earlier. It is not surprising then that early advertising for Society Make-up concentrated on cementing the link between Max Factor, Hollywood and movie stars, rather than detailing the products in question.

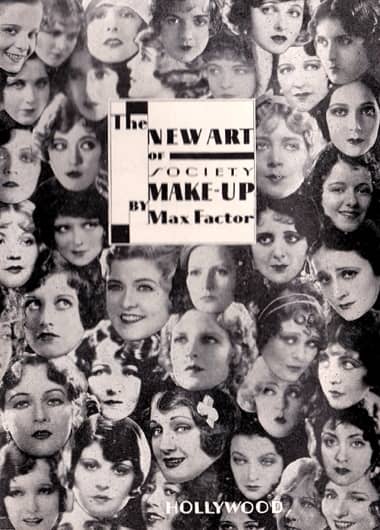

Also see the booklet: The New Art of Society Make-up (1929)

In all likelihood the driving force behind the creation of the Society range came from Max Factor’s older children, Frank and Davis Factor, rather than from Max himself. The name ‘society’ was probably selected because of its associations with status and respectability – an idea Pond’s had also used when they began using society ladies in product endorsements in 1924. The word ‘make-up’ was used, rather than ‘cosmetics’, to associate the line with motion pictures and the movie stars that featured in Max Factor advertising – people used cosmetics, movie stars used make-up.

To some women the new word “make-up” may only mean the application of powder, or powder and rouge, or perhaps powder, rouge and lipstick. To others, make-up may only mean the theatrical use of cosmetics. Neither impression is correct, and both have therefore resulted in the wrong use of cosmetics by thousands of women. The expression “paint and powder” and the criticism of a “painted” appearance may also be attributed to the wrong understanding and the incorrect use of make-up.

(The new art of society make-up, 1928, p. 9)

Color Harmony

Color Harmony principles were promoted as the basis of the Society Make-up line. Max Factor considered Color Harmony to be one of the ‘three secrets of make-up’. Women who were unfamiliar with cosmetics could use it to select the appropriate shade of make-up their particular colouring.

Make-up Easy … If You Learn These Secrets

To accomplish this effect is easy if you know what constitutes make-up; if you learn the correct method of make-up; and if you select the correct color harmony to blend with your natural complexion.

First, then, make-up requires that each feature which adds to beauty must be considered individually and as a part of the harmonious whole. The face, the eyes, the lips, the neck, the arms, the hands, the hair—each should be beautified.

Second, make-up should not be used in a haphazard fashion, but should be applied according to certain well-defined principles of art and cosmetic science.

Third, all cosmetics used must be in perfect color harmony with the individual complexion, or else they clash, producing an unnatural, grotesque effect.(The new art of society make-up, 1931, p. 11)

Given the large number of possible colour combinations of skin, hair and eyes, the selection process was made easier by dividing the colour harmonies into four broad groups based on hair colour – Blondes, Brunettes, Redheads and Brownettes (a category invented by Max Factor himself) – with occasional references to a fifth type, Titian.

Above: Max Factor window display for Society Make-Up with the four color harmony types, Blondes, Brunettes, Redheads and Brownettes.

Grouping individuals into types was also not a new idea. It was used by many cosmetic companies in the 1920s which is perhaps why Basten (1995) credits Max Factor with first developing ‘Color Harmony’ in 1918, an unverified claim.

Also see: Make-up, Personality and Types

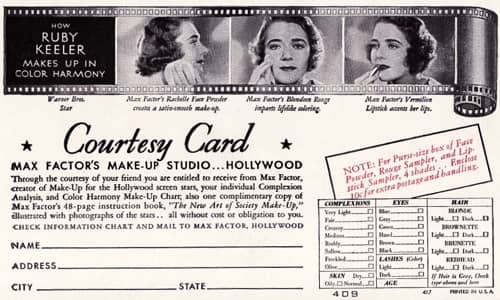

Women could get suggested make-up shades suited to their colouring by filling in a form and sending this to the company. By return mail they would get some skin-care and make-up advice along with a copy of the company booklet ‘The New Art of Society Make-Up’.

Above: 1930s Max Factor Courtesy Card. These could be mailed in for a free complexion analysis, Color Harmony Make-Up Chart and booklet.

Later versions of this booklet described the hair, eye and skin colours of movie stars who represented each of the four types, followed by a list of the Max Factor make-up appropriate for their particular colouring. This enabled women to emulate the make-up of movie stars they perceived as closest to them in colouring or, as was increasingly the case, to dye their hair and change their make-up to look more like their favourite actress.

The reasoning used to explain Color Harmony seems reasonable but the story describing its development is less so when you realise that most films of the time were shot in black and white.

Dream a moment … then fly on the wings of imagination to Hollywood … It is night-time at one of the big studios … A Rolls-Royce silently and gracefully rolls up to the entrance … The star alights and hurries to her dressing room … At her make-up table Max Factor is interestedly working … There is something new tonight … The genius in make-up has developed another discovery … tonight color pigments will be harmonized in cosmetics for the first time … As the star is being made up she wonders if the experiment will be a success … The camera will tell, for the camera never lies … On the set, under the “Klieg” lights, the director marvels at her radiant beauty … Max Factor enthusiastically smiles approval … Intuitively she senses a success as the camera starts clicking … Now, later … the review of the film in the projection room … and as the scene flashes on the screen, the rare beauty of the star appears so lovely, so natural, so alluring, that Max Factor realizes the severe test of the Kleig lights has caused him to develop a revolutionary idea in cosmetics.

Thus, the science of cosmetic color harmony was discovered.(The new art of society make-up, 1928, pp. 6-7)

As well as providing a rationale for its general make-up, Color Harmony was considered important to the company for another reason. Sales Builder, who distributed Max Factor products, quickly realised its potential sales benefits. As they saw it, Color Harmony helped sales because it encouraged women to ‘harmonise’ their cosmetics, that is, to buy all their make-up from the one brand, rather than in an haphazard fashion. This was the make-up equivalent of the skin regimes that companies like Helena Rubinstein, Elizabeth Arden and Dorothy Gray had developed to encourage customers to buy all their skin treatment products from the one line.

Also see the company booklet: Color Harmony Make-Up with an All Star Cast (1929)

Panchromatic make-up

In 1928, one year after Max Factor introduced its Society range, events occurred that would further cement the relationship between Max Factor and the movie industry. In that year, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences conducted a series of tests – involving lighting, cameras, film and make-up – at the Warner Brothers Studios. Known as the Mazda tests, they established incandescent lighting and panchromatic film as industry norms.

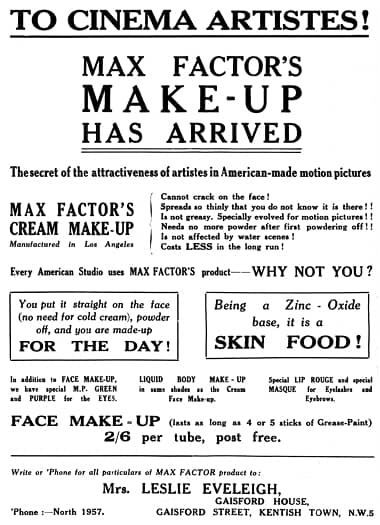

During the four months in which the tests were conducted Max Factor developed a make-up that worked well with panchromatic film and incandescent lighting. Known as Panchromatic Make-up it was quickly adopted by most Hollywood studios followed by film studios around the world. Soon, large quantities of Max Factor Panchromatic Make-up were being shipped overseas to Max Factor agencies established in London, England; Sydney, Australia; Shanghai, China; Durban, South Africa; Honolulu, Hawaii; and Toronto, Canada.

See also: Panchromatic Make-up

Reorganisation and expansion

The widespread adoption of Panchromatic Make-up and the launching of the Society Make-up range required some reorganisation of the company as it expanded its operations. In 1927, a branch office and warehouse was opened at 444 West Grand Avenue, Chicago. In 1928, the Max Factor Sales Corporation was established at 945 Wall Street, Los Angeles to handle distribution in the United States, with Louis Conrad (President), Hess M. Kramer (Vice-president) and Harry A. Mier (Secretary-treasurer). Max Factor also established an export business under the direction of Ismael R. Alvarez. He would defect to the Westmores in 1935.

See also: The House of Westmore

In 1929, Max Factor & Company then re-incorporated under the more company friendly Delaware legislation. Its officers were largely drawn from Max Factor’s extended family: Max Factor remained the company president; Max Firestein, who married Cecelia Factor in 1923, and had a history in sales, was made vice-president; and Davis Factor took up the role of secretary-treasurer. Frank Factor, Louis Factor, and Abe B. Shore were also involved in the business.

The year 1929 was important for another reason. The Wall Street crash on October 20, 1929 would usher in the Great Depression that lasted for much of the following decade.

Timeline

| 1905 | Max Factor opens a barber shop at 1513 Biddle Street, St. Louis, Missouri. |

| 1909 | Max Factor’s Antiseptic Hair Store opens at 1204 South Central Avenue, Los Angeles. Max Factor & Company founded. |

| 1916 | Max Factor moves to 326 South Hill Street. |

| 1923 | New Products: Supreme Greasepaint. |

| 1927 | Max Factor opens branch office at 444 West Grand Avenue, Chicago. New Products: Society Make-up range; Society Nail Tint; and Society Nail White. |

| 1928 | Max Factor’s Make-up Studio opens, complete with salon, at 1666 North Highland Avenue, Hollywood. Max Factor agency established in London. Max Factor Sales Corporation founded. New Products: Panchromatic make-up. |

| 1929 | Max Factor & Company becomes a Delaware corporation. Max Factor receives an Oscar for make-up. |

Continue to: Max Factor (1930-1945)

First Posted: 19th August 2013

Last Updated: 22nd January 2023

Sources

75 years of Max Factor. (1984). Manufacturing Chemist. January, 49.

Anderson, K. (2001). “Go West”: The representation of Los Angeles in silent film comedy [Electronic version]. Spectactor. 21(1). 82-90.

Basten, F. E. (1995). Max Factor’s Hollywood. Glamour, movies, make-up. Los Angeles: General Publishing Group.

Basten, F. E. (2008). Max Factor: The man who changed the faces of the world. New York: Arcade Publishing.

Color harmony make-up by Max Factor with an all star cast [Booklet]. (1929). Hollywood: Max Factor Studios.

Factor, M. (1928). Movie make-up. American Cinematographer, 10(1), 8, 25.

The new art of society make-up [Booklet]. (1928). Hollywood: Max Factor Studios.

The new art of society make-up [Booklet]. (1929). Hollywood: Max Factor Studios.

Peiss, K. (2007). Hope in a jar: The making of America’s beauty culture. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Young, J. (1905). Making up. A practical and exhaustive treatise on this art for professional and amateur. New York: M. Witmark & Sons.

Max Factor [1872-1938]. Born Maximilian Faktorowicz, he received his anglicised name when he arrived in America. Max Factor’s naturalisation petition (1906) gives his birth date as December, 3, 1875 and his passport application (1922) list it as May 15, 1875. However, his mother, Celilia Factrowitz, née Tandowsky, was believed to have died of cholera in 1874 so neither of these dates can be correct.

1904 Esther (Lizzie) [1877-1906], Max, Freda [1898-1988], Cecilia [1899-1984] and Davis Faktorowicz in Russia. Frank was born in St. Louis after the family arrived in the United States. Max had two additional children: Louis Factor [1907-1975] from his second marriage, and Sidney Factor [1916-2005] from his third marriage to Jenny Cook [1886-1949].

Davis Factor [1902-1991].

Frank Factor [1904-1996].

1914 Squaw Man.

c.1917 The Pantages Building.

Interior of the Max Factor store in South Hill Street showing a cabinet containing Max Factor Supreme make-up. The sign at the bottom left reads ‘Max Factor Highest Grade Make-up’.

1922 Max Factor & Co. (The House of Make-up) in South Hill Street.

1916 The Hollywood Fireproof Storage Co. building at 1666 North Highland Avenue, built by C.E. Toberman. After it was refurbished this became the home of the Max Factor Make-up Studio in 1928.

Max Factor Make-up Studio on North Highland Avenue, Hollywood. The increasing number of make-up artists working in Hollywood during the 1920s led to the establishment of the Motion Picture Make-up Artists Association in 1927. It made its headquarters in this building and the association held weekly meetings during which make-up demonstrations were given by its members.

1923 Max Factor make-up being sold through agents in New York.

1925 Max Factor testing make-up on the French actress Renée Adorée (Jeanne de la Fontein) [1898-1933].

1925 Don Q Mark of Zorro poster. This may have been the movie in which Douglas Fairbanks tested Max Factor’s Supreme Greasepaint.

1927 Announcement that First National has relocated to California. This was the last of the big producing organisations to do so.

1927 Max Factor Supreme Cosmetics. Also mentions Society Make-up.

1927 Max Factor Society Make-up.

1927 Max Factor British Distributer. Mrs. Leslie Eveleigh was the wife of the British actor, Leslie Eveleigh [1890-1939].

1928 Interior of the Max Factor Make-up Studio in North Highland Avenue fitted out in Louis XVI style.

c.1928 Assembling compacts at North Highland Ave.

1928 Max Factor Society Make-up.

1928 Max Factor Society Make-up. Readers were encouraged to write away for a free booklet first published in 1928.

1928 Max Factor Society Make-up.

1929 Max Factor Panchromatic Make-Up as used by various film studios. It was also available through agents in Britain, Australia, China, Hawaii, South Africa and Canada.

Max Firestein (Feuerstein) [1894-1990], vice-president of Max Factor & Co.

Abe B. Shore [1894-1957], Freda Factor’s first husband. He resigned from Max Factor in 1948.

1929 Max Factor Theatrical Make-Up. Note the three addresses. The South Hill store closed in 1930.

Max Factor’s Cosmetics of the Stars advertising stand featuring Esther Ralston (1902-1994).

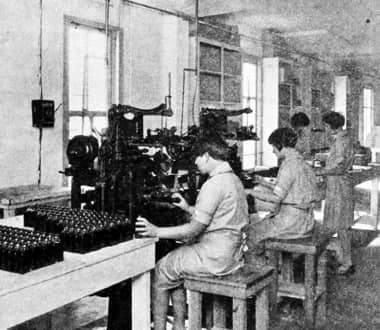

c.1929 Labeling bottles at North Highland Ave.

c.1929 Filling Brillox bottles at North Highland Ave.

1929 The New Art of Society Make-up by Max Factor.

1929 Max Factor Society Make-up.

1929 Max Factor Society Make-up.

1929 Max Factor Society Make-up. Sun Tan products are given special mention at the bottom of the advertisement; an indication of the strength of the sun tan craze of the 1920s.

Tins of Max Factor Supreme and Panchromatic Face Powder.

1930 Max Factor’s Make-up. Originators of Panchromatic and Technicolor Make-up.

1930 Max Factor Make-up Studios.