Odorono

In 1909, Dr. Abraham D. Murphey [1863-1935] of Cincinnati, Ohio registered Odor-o-no as a trademark for a toilet lotion he had developed to prevent excessive perspiration. The generally accepted story about the origin of this antiperspirant is that Dr. Murphey created it to control his sweaty palms during surgery on hot days.

In 1910, Murphey’s daughter, Edna Grace Murphey, borrowed some money, opened an office in Cincinnati and began trying to sell Odor-o-no to a wider market. Her efforts met with limited success. Most people thought either that they did not need an antiperspirant or that checking perspiration would be detrimental to their health.

“For over three years I hardly moved out of the house,” she tells me, “and I cannot recall accepting a single social invitation. Yet at every stage of development there was an increased inspiration from users–and along with it increased discouragement. It cost so much to make a new user, it took so long to convince anyone that checking perspiration would not affect their health.

(Woolley, 1923, p. 940)

The idea that antiperspirants were harmful was in line with a prevailing belief that the pores of the skin were essential for the removal of harmful substances from the body, a viewpoint also held by many health professions.

See also: Enlarged Pores

Unable to generate enough sales to pay the rent Edna Murphey moved her business back home but did not give up.

“A few drug stores did put Odo-ro-no on consignment, but with few exceptions we took the bottles back. Sales of our star canvassers sometime ran six dollars a day; and agents in small surrounding towns were also secured, and later in small southern towns. On their sales we kept going.

(Woolley, 1923, p. 940)

In the summer of 1912, Edna sent quantities of Odor-o-no to be exhibited in Atlantic City, then a popular summer destination.

Above: 1912 Atlantic City. Note the use of umbrellas for shade on the boardwalk.

Edna suggests that she chose Atlantic City to coincide with an exposition. I have been unable to find any records of an exposition in Atlantic City around this time that would be likely to attract her attention but between May and June of 1912, nine American medical associations – including the Association of American Physicians (AAP) and the American Medical Association (AMA) – held their annual meetings there. These visiting health professionals and their wives, coupled with the usual summer visitors to Atlantic City, may have been the reason for Edna setting up a booth there.

At first, business was slow but the situation improved as the summer developed and the weather got warmer.

About 1912 we took a booth at an Atlantic City exposition, but the demonstrator could not sell any Odo-ro-no at first and wired us for cold cream–to sell and pay expenses. We bought and sent down five gallons. The exposition lasted all summer, and through it ultimately we obtained users in all parts of the country, and through these made dealer connections.

(Woolley, 1923, p. 940)

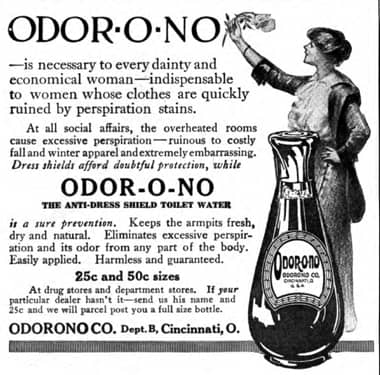

After Atlantic City, Murphey began advertising Odor-o-no more widely through newspapers in major cities. Early advertisements were written by Edna like advertorials but a dealer’s name was included at the bottom if there was one in the vicinity of the newspaper’s readership.

Above: 1912 Odor-o-no advertorial in the Evening Star (Washington, D.C.).

In 1913, Odor-o-no advertisements began to include graphics. The copy was still written by Edna but the images were probably created by the artist John Bertrand Alberts Jr. [1887-1931] whom Edna married in 1914.

J. Walter Thompson

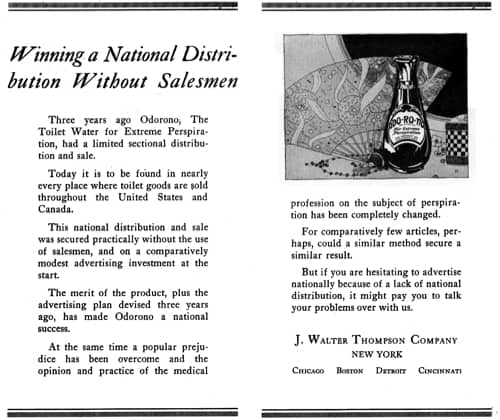

1914 was a big year for Odorono in other ways. After taking out a US$50,000 bank loan, Edna hired the J. Walter Thompson (JWT) agency to conduct Odorono’s national advertising campaign. Starting with an initial allocation of US$14,000 this rose to US$270,000 by 1920 (Woolley, 1923). Odorono did not hire its first salesman until 1914, and there were only four on the company’s payroll in 1920, so most of the sales growth between 1914 and 1920 could be put down advertising.

Above: 1917 J. Walter Thompson promoting the success of its Odorono advertising campaign.

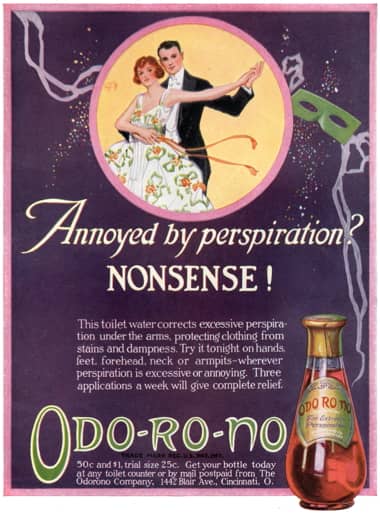

J. Walter Thompson put James Young in charge of the Odorono account. He had been hired in 1912 by JWT to work as a copywriter in their newly opened Cincinnati office. Early Odorono advertisements concentrated on combating the idea that using an antiperspirant was unhealthy and stressing that it had been developed by a doctor.

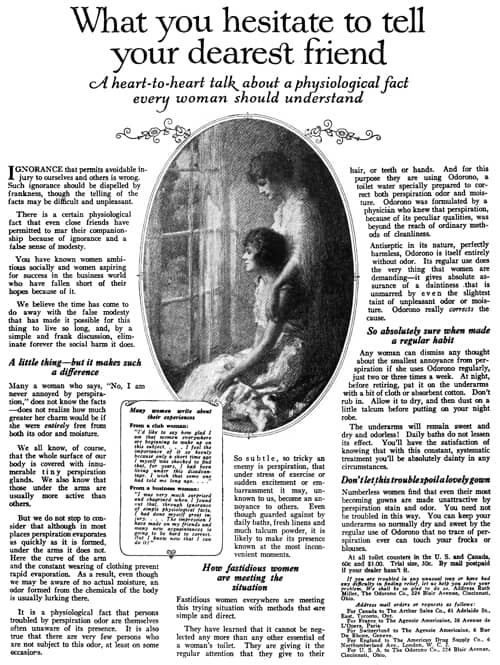

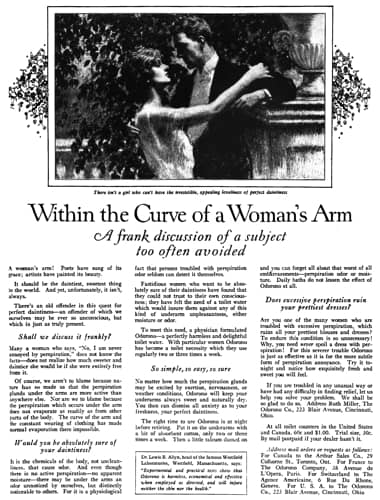

When Odorono sales started to level off in 1919, Young switched from promoting Odorono as a remedy for perspiration to convincing people – women in particular – that sweating was an embarrassing personal problem that could make you smelly and offensive.

This was an early example of what was later called ‘whisper-copy’ – insinuating that a problem might exist that people were too polite to tell you about (Everts, 2012). The ‘whisper-copy’ advertisements Young developed for Odorono were considered shocking at the time but Odorono sales rose 112 percent to US$417,000 in 1920; results that ensured that this type of advertising was widely emulated.

1919 An example of a ‘whisper-copy’ advertisement developed by James Young for Odo-ro-no.

Young may also have been responsible for the creation of Ruth Miller, a presumably fictitious Odorono consultant that women could write to for advice on perspiration problems.

Odo-ro-no

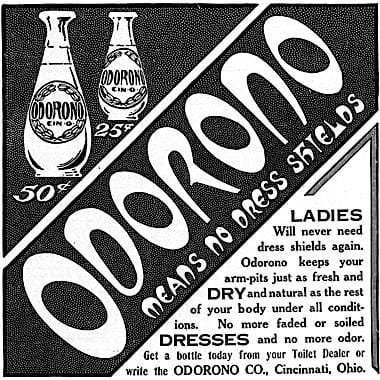

In 1914, Odor-o-no became Odo-ro-no for the first time. The reason behind the name change is unknown to me but it may simply have been to match the written name with its usual pronunciation after allowances were made for metathesis.

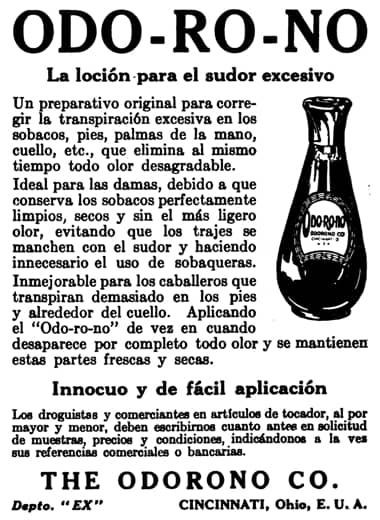

By 1915, the company was doing so well that Edna moved the business out of home once more, this time into a small factory and office she constructed in Blair Avenue, Cincinnati. The additional income also enabled her to hire Mr. E. R. Brunskill as the company chemist. Furthermore, she began selling Odo-ro-no outside of the United States, starting with Cuba and England. By 1921, Odo-ro-no was also being advertised through newspapers and magazines in Mexico, The Philippines, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, Argentina, New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa.

Product development

In 1913, Odor-o-no was examined by the Chemical Laboratory of the American Medical Association (AMA) which found it to consist of largely of aluminium chloride and water, with the former making up about 33% of the solution. The AMA thought that Odor-o-no was likely to cause underarm irritation and clog the skin’s pores which made it dangerous.

Evidently the rumor that the manufacturers of “Odor-o-no” had changed their formula is without foundation. The stuff is essentially what it was more than a year ago, a solution of aluminum chlorid. When “Odor-o-no” is placed on the skin, the perspiration decomposes it into aluminum hydroxid and hypochloric (muriatic acid). The acid of course will attack the skin, while the aluminum hydroxid (or oxid) is apt to clog the pores. The preparation is both fraudulent and dangerous.

(The propaganda for reform, 1914, p. 54)

The level of aluminium chloride in Odor-o-no was very high – other antiperspirants marketed in the 1920s used concentrations of aluminium salts at 25% or less – and there were reports of women developing skin ulcers after using it.

W. D. McAbee, a chemist of the [Indiana] State board of health, who has been investigating “fake” health and toilet remedies for some time, says he has found another remedy that not only is sold at a high price, but that is positively injurious when used as prescribed.

The remedy is Odor-o-no, manufactured in Cincinnati, and sold for 25 cents a bottle, as a preventive of perspiration. Mr. McAbee, in exposing the remedy, said it is a solution of aluminum chloride, a material used extensively as an external disinfectant. When the material dries on the skin, Mr. McAbee declares that it decomposes and forms hydrochloric acid, which attacks almost every type of skin violently. Several instances have come to the at attention of the State board, he says, in which the remedy has caused ulcers.(The Druggists Circular, 1912, p. 625)

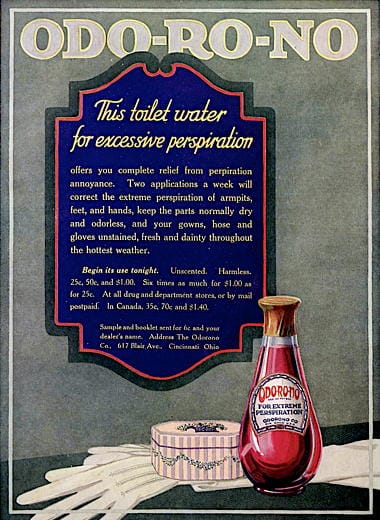

As well as the irritation problem, Odo-ro-no was difficult to apply and some users even objected to its red colour. Unlike modern antiperspirants it was only meant to be used 2-3 times a week and was to be applied at night so that it had time to dry.

Use Odorono regularly, just two or three times a week. At night before retiring, pat it on the underarms. Allow it to dry, and then dust on a little talcum. The next morning, bathe the parts in clear water. The underarms will remain sweet and dry and odorless in any weather, in any circumstances. Daily baths do not lessen its effect.

(Odorono advertisement, 1919)

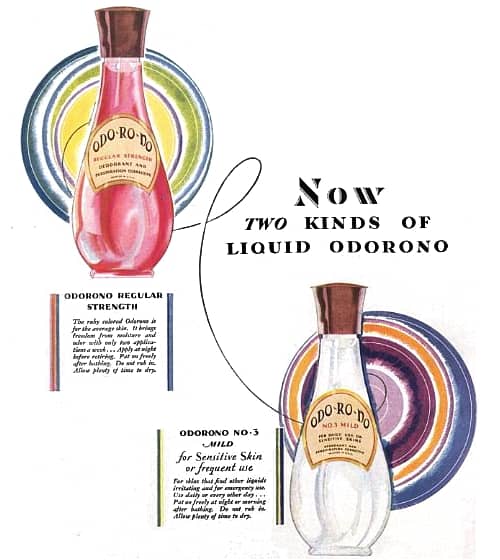

It is possible that the concentration of aluminium chloride in the original Odo-ro-no was lowered over time but it was not until 1928 that the company produced an antiperspirant with much lower levels of aluminium salts. The new product was called called Odo-ro-no No. 5 and, as well as being milder, it was also colourless.

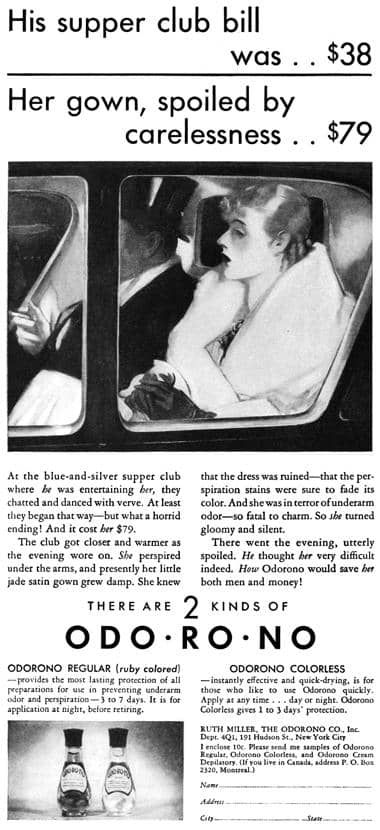

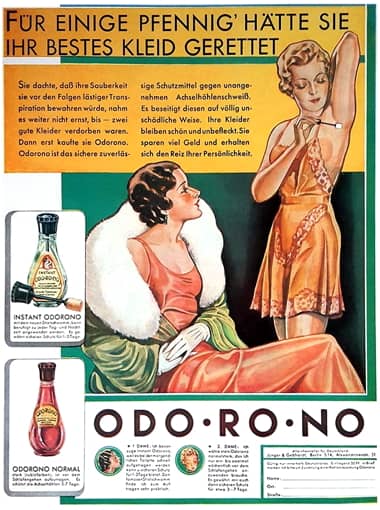

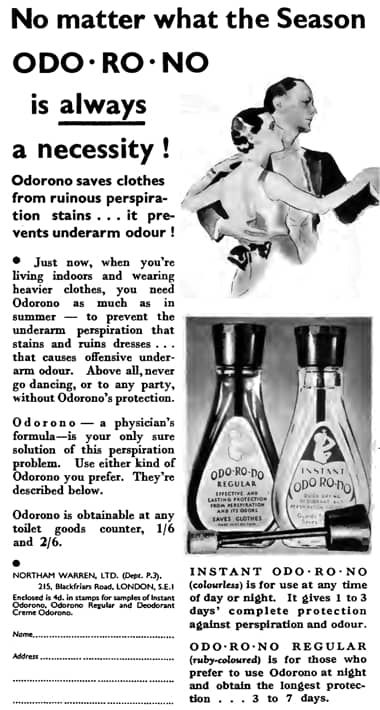

There are now two kinds of Odorono.

The ruby colored, full strength, which checks moisture and odor used once or twice a week, the last thing at night. And Odorono No. 5, colorless, milder, lasts only a day or two but can be used night or morning and on sensitive skins.(Odorono advertisement, 1928)

There appear to have been concerns with the formulation as the following year, Odo-ro-no No. 5 was replaced with Odo-ro-no No. 3 but by then Odorono was part of Northam Warren.

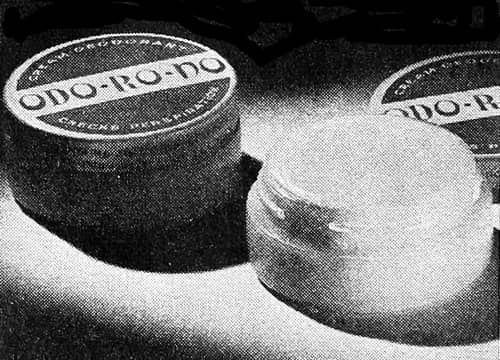

Above: 1929 Odo-ro-no Regular Strength and Odo-ro-no No. 3 Mild.

Other products

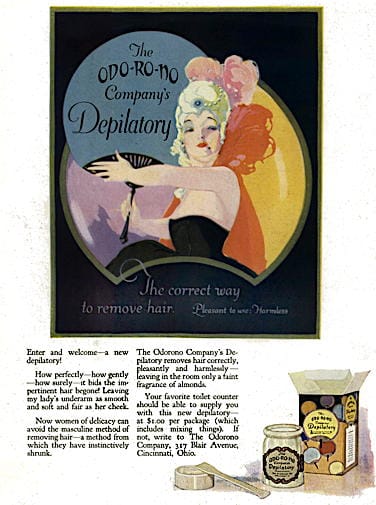

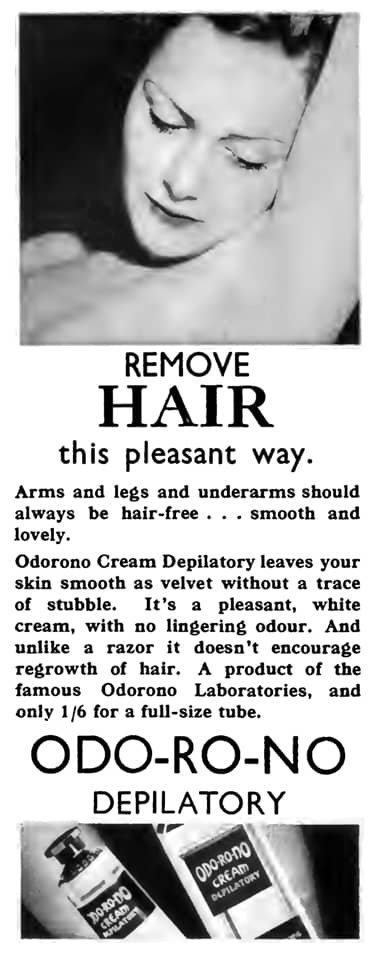

In the 1920s, Edna expanded Odorono’s product line to include a depilatory. Introduced in 1920, it was sold as a powder to be mixed with water into a paste at home. The following year, Odorono added After Cream to soothe the skin after the Odo-ro-no depilatory or antiperspirant had been used – a clear indication that there were irritation problems with both products.

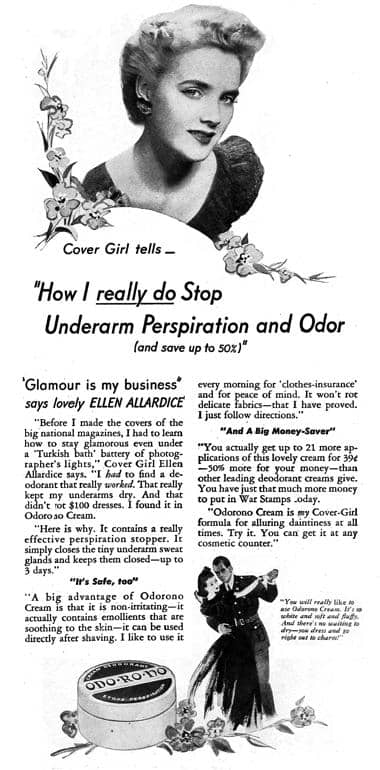

Odorono also introduced two deodorants during the 1920s: Creme Odo-ro-no in 1922, followed by Odorono Powder Deodorant in 1928. Neither product appears to have contained an antiperspirant.

Mention should also be made of Glazo which made nail polishes and other manicure items. Edna did not start this product line but rather bought The Glazo Company of Fort Wayne, Indiana and then incorporated the company in Cincinnati in December, 1918 with a capital stock of US$25,000. After the purchase, Glazo’s headquarters were moved to Blair Avenue, Cincinnati but it remained a separate company and I will not examine it in any detail here.

Sale

In 1928, Edna Murphey sold Odorono and Glazo to Northam Warren, for a reputed sum of US$3.5 million. As is common with a lot of company founders after they sell to a larger concern, Edna appears to have difficulties with the new owners and left the company within a few years.

See also: Northam Warren

In 1932, Edna remarried, this time to Ezra Augustus Winter [1886-1949], a successful artist perhaps best known for his Fountain of Youth mural at the Radio City Music Hall in the Rockefeller Center. The couple maintained a residence in New York and purchased land in The Berkshires in Canaan, Connecticut in 1933 and established an estate there they called Juniper Hill. Edna, now known as Patricia (Pat) Winter, created a herb garden on the estate and then built a business around it called the House of Herbs. She then developed and sold a herbal hair rinse called Tressglo.

Above: Edna (Pat) Winter in her herb garden at Juniper Hill.

Northam Warren

Following its purchase of Odorono, Northam Warren moved Odorono’s headquarters to 191 Hudson Street, New York. Odorono had been doing well prior to its change of ownership with net profits of US$354,623 (1926), US$483,176 (1927) and US$630,000 est. (1928) but the 1930s would see the line come into increasing difficulties.

In 1931, Northam Warren tried to fix the application problem by introducing Instant Odo-ro-no with an in-built sponge applicator. The formula for this new product is unknown to me but it may have been similar to Odo-ro-no No. 3 introduced in 1929. A similar applicator was soon added to the original Odo-ro-no as well.

Above: 1931 Instant Odo-ro-no with moulded cap and applicator. The dauber is made from sponge rubber embedded in a screw cap of black ‘Durez’ plastic.

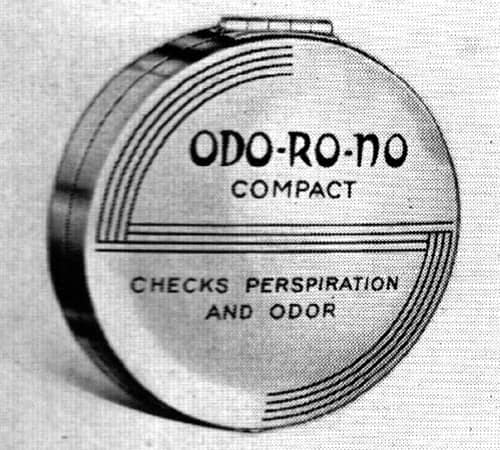

In an attempt to make Odo-ro-no antiperspirant more portable, Northam Warren released Odo-ro-no Compact in 1933. The compact powder was packaged in a metal case designed to be carried in a purse and applied when needed, like a face powder, using the included lambswool puff. Odorono went as far as suggesting that it could even be used to correct a shiny nose.

Odo-ro-no Compact: “Checks Perspiration and Odor. Use as often as necessary, under the arms or wherever perspiration occurs. (Good for a shiny, perspiring nose or chin.) As simple, easy and pleasant to use as your vanity—carry it in your purse; keep one in your desk, to ensure personal daintiness at all times.”

Above: 1933 Odo-ro-no Compact.

In 1936, the antiperspirant market changed direction when Feminine Products – a division of Carter Medicine – introduced Arrid, an antiperspirant cream made with aluminium sulphate. Although less effective than Odo-ro-no it was easier to apply. Arrid rapidly captured a large segment of the antiperspirant market and ultimately led to the demise of liquid antiperspirants packaged like Odo-ro-no.

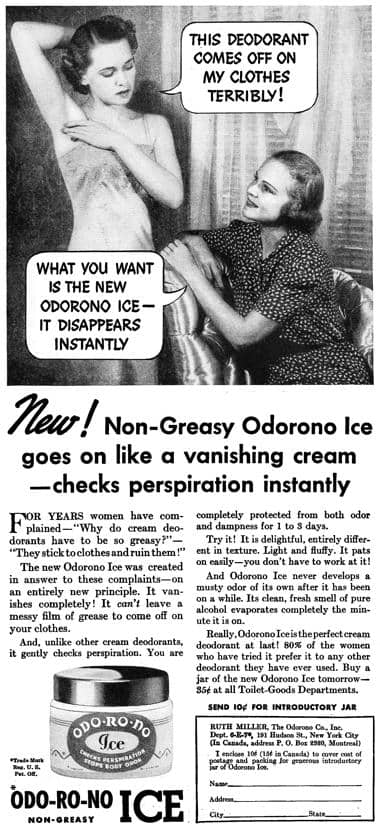

The following year, Northam Warren released Odo-ro-no Ice. It went on like a vanishing cream but contained alcohol to give it a cool feeling when applied. It was discontinued during the Second World War but had reappeared by 1946.

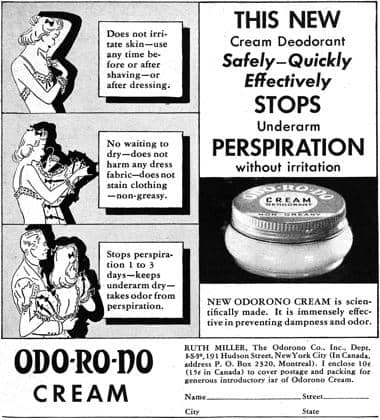

In 1939, Northam Warren also added a cream deodorant and antiperspirant made with zinc sulphocarbonate and ammonium aluminium sulfate. Called Odo-ro-no Cream Deodorant – despite it also being an antiperspirant – it was originally packaged in a glass jar with a screw-cap lid. After the outbreak of the Second World War this container was replaced with plastic, only returning to glass in 1944.

Above: 1944 Odo-ro-no Cream Deodorant in a glass container with a screw-top lid.

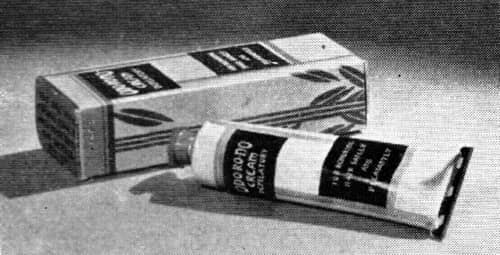

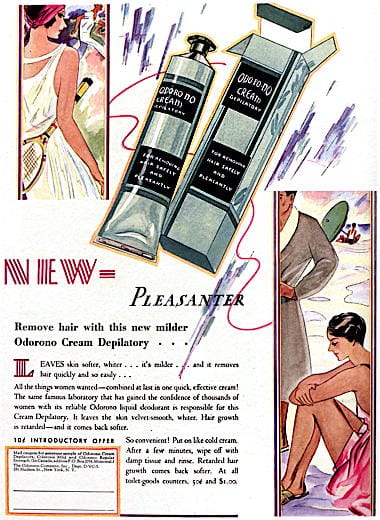

Northam Warren also updated the Odo-ro-no depilatory, introducing Odo-ro-no Cream Depilatory in 1930. In 1932, the product was improved by changing its cream colour to pure white and by adding a perfume.

Above: 1932 Odo-ro-no Cream Depilatory.

Post-war

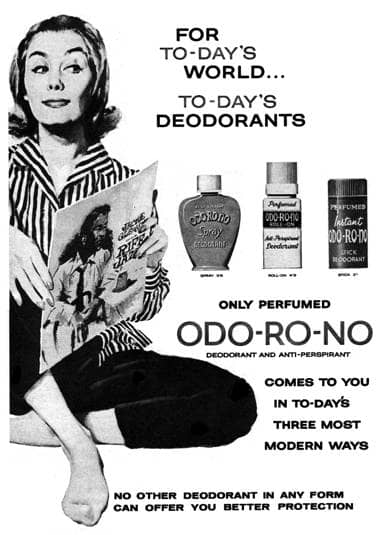

In the same way that Arrid changed the deodorant and antiperspirant market in 1936, the post-war deodorant and antiperspirant market was similarly shaped by the introduction of new delivery systems, such as squeeze bottles, roll-ons and aerosols, as well as new ingredients, including hexachlorophene, antibiotics and zirconium salts. Innovators in this field generally picked up a substantial share of the deodorant and antiperspirant market. Northam Warren failed to develop a successful innovation and this contributed to the general decline of the Odo-ro-no product line.

See also: Deodorants & Antiperspirants

New Odo-ro-no products developed by Northam Warren after the War generally relied on ideas developed by other companies. New Odo-ro-no lines included:

1. Odorono Spray Deodorant (1950) using a squeeze container similar to the polyethylene one developed by Jules Montenier for Stopette in 1947. A smaller version was introduced in 1954.

Above: Odo-ro-no Spray Deodorant.

Odo-ro-no Spray Deodorant: “Banishes odor instantly. Stops perspiration quickly. Keeps you sweet and lovely for days Harmless to all fabrics. Unbreakable, spray bottle.”

See also: Stopette

2. Instant Odorono Stick Deodorant (1956) containing a zirconium salt to reduce perspiration, hexachlorophene to kill odour-causing bacteria and allantoin to heal razor nicks and other irritations. Zirconium salts had been previously suggested as antiperspirants by Van Mater (US Patent: 2498514, 1950) and hexachlorophene had first been used as a deodorant in Dial Soap in 1948.

See also: Hexachlorophene

3. Odo-ro-no Satin Sponge (1958), a liquid deodorant and antiperspirant. This appears to have been a Northam Warren innovation but unfortunately, not a successful one. It was clumsy as after each use surplus liquid had to be wiped off and the neoprene-sponge applicator rinsed under water. The product was also prone to evaporation if the clear nylon cap was not screwed on tightly.

Above: Odo-ro-no Satin Sponge made using aluminium chlorhydroxide as an antiperspirant.

Above: The applicator head of an Odo-ro-no Satin Sponge.

Odo-ro-no sponge deodorant: “[A]pplies easily – covers as no roll-on deodorant can – dries quickly – leaves no lotion stickiness – harmless to normal skin – gives 24 hour guaranteed ANTIPERSPIRANT protection.”

4. Odo-ro-no Roll-on (1959) emulating Ban, the first commercially successful roll-on antiperspirant developed by Bristol-Myers in 1954.

See also: Ban

Chesebrough-Pond’s

By the late 1950s Northam Warren was ailing. In particular, sales of its nail polishes and lipsticks – Cutex, Glazo and Peggy Sage – were been adversely affected by the rise of Revlon. In 1960, Northam Warren sold out to Chesebrough-Pond’s and this is where my interest in Odorono largely ends.

See also: Chesebrough-Pond’s

Later developments

Chesebrough-Pond’s was acquired by Unilever N.V. in 1986 and the company abandoned the Odo-ro-no brand in preference to Rexona, an Australian brand name acquired by Lever Brothers (later Unilever) around 1930.

Above: Rexona Odorono.

Rexona is the deodorant and antiperspirant brand Unilever sells in most countries in which it operates but substitutes it with other brands – such as Sure, Degree, Rexena and Shield – in some markets, a reflection of the complex product history of this multinational company.

Having abandoned the brand, Unilever sold the Odorono trademark for the USA, Mexico and the Caribbean to Omega & Delta Company, Inc. in 2003. Omega & Delta then bought the Odorono trademark for Central America, South America and Europe from Unilever in 2006.

Timeline

| 1909 | Odor-o-no trademark registered. |

| 1910 | Office opened in Cincinnati. |

| 1912 | Advertising begins. |

| 1914 | Product name changed from Odor-o-no to Odo-ro-no. J. Walter Thompson given the advertising account. |

| 1915 | Office and factory built in Blair Avenue, Cincinnati. |

| 1918 | First full-time salesman hired. |

| 1920 | New Products: Odo-ro-no Depilatory. |

| 1921 | New Products: Odo-ro-no After Cream. |

| 1923 | New Products: Creme Odo-ro-no. |

| 1928 | Odorono acquired by Northam Warren. New Products: Odorono Deodorant Powder; and Odo-ro-no No 5. |

| 1929 | Odorono offices moved to 191 Hudson Street, New York. New Products: Odo-ro-no No 3. |

| 1930 | New Products: Odo-ro-no Cream Depilatory. |

| 1931 | New Products: Instant Odo-ro-no. |

| 1932 | Odo-ro-no Cream Depilatory reformulated. |

| 1933 | New Products: Odo-ro-no Powder Compact. |

| 1937 | New Products: Odo-ro-no Ice. |

| 1939 | New Products: Odo-ro-no Cream Deodorant. |

| 1946 | Odo-ro-no Cream reformulated with Halgene. |

| 1956 | Instant Odo-ro-no reformulated with hexachlorophene. |

| 1958 | New Products: Odo-ro-no Satin Sponge. |

| 1959 | New Products: Odo-ro-no Roll-on. |

| 1960 | Northam Warren bought by Chesebrough-Pond’s. |

| 1987 | Chesebrough-Pond’s acquired by Unilever. |

| 2003 | Omega & Delta acquire the Odorono trademark for USA, Mexico and the Caribbean from Unilever. |

| 2006 | Omega & Delta acquire the Odorono trademark for Central America, South America and Europe from Unilever. |

First Posted: 11th July 2017

Updated: 28th February 2024

Sources

Applegate, E. (1994). The ad men and women: A biographical dictionary of advertising. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

The Druggists Circular. (1912). Volume 56. New York: Author.

Everts, S. (2012). How advertisers convinced Americans they smelled bad. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved February 26, 2014, from http://www.smithsonianmag.com/

history/how-advertisers-convinced-americans-they-smelled-bad-12552404/?all

Fox, S. (1984). The mirror makers: A history of American advertising and its creators. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Helfand, J. (2012). Ezra Winter project: Chapter 4. Retrieved June 24, 2017, from http://designobserver.com/

feature/ezra-winter-project-chapter-four/33818

Helfand, J. (2012). Ezra Winter project: Chapter 10. Retrieved June 24, 2017, from http://designobserver.com/

feature/ezra-winter-project-chapter-ten/36948

The propaganda for reform. (1914). Journal of the American Medical Association, January 3rd, p. 54.

Sivulka, J. (2008). Odor, oh no! Advertising deodorant and the new science of psychology, 1910 to 1925. Journal of Macromarketing, 28, 212-220.

Woolley, E. M. (1923). How much does it take to advertise? Sales Management, 5(11), 939-940, 1030.

Edna Grace Albert (née Murphey) [1887-1969] also known as Patricia (Pat) Winter.

1912 Odor-o-no.

1913 Odor-o-no.

1913 Odorono. Odorono briefly dropped all the hyphens from the product name.

1914 Odo-ro-no.

1915 Odo-ro-no.

1916 Odo-ro-no.

1917 Odo-ro-no aimed at men.

James Webb Young [1866-1973] from J. Walter Thompson. The success of his ‘whisper-copy’ for Odorono made him famous within the advertising community.

1919 Odo-ro-no. After James Young placed this advertisement in the ‘Ladies Home Journal’ some readers canceled their subscription to the magazine.

1920 Odo-ro-no Depilatory.

1925 Odo-ro-no available as a liquid antiperspirant as well as a deodorant cream in a tube (France).

1930 Odo-ro-no Cream Depilatory.

1931 Odo-ro-no Regular and Odo-ro-no Colorless.

1932 Instant and Normal Odo-ro-no (Germany).

1934 Instant Odo-ro-no.

1934 Odo-ro-no Cream Depilatory.

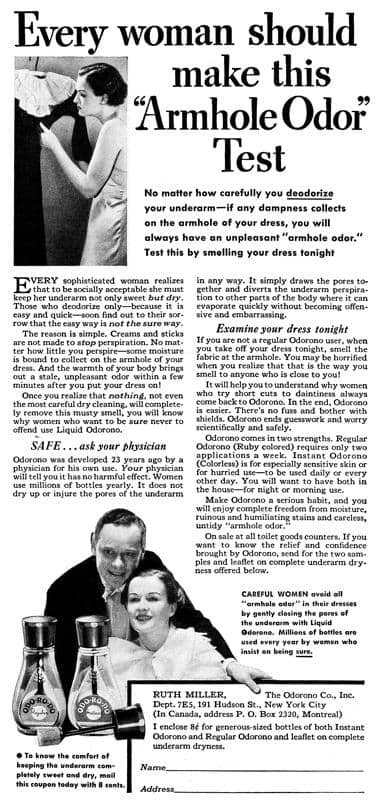

1935 Odo-ro-no ‘Armhole Odor’. This advertisement tries to emulate Lifebuoy’s highly successful body odour (B.O.) campaign.

1937 Odo-ro-no Ice.

1939 Odo-ro-no Cream Deodorant in pre-war packaging. The glass container would be replaced with plastic during the Second World War.

1943 Odo-ro-no Cream deodorant and antiperspirant in wartime packaging.

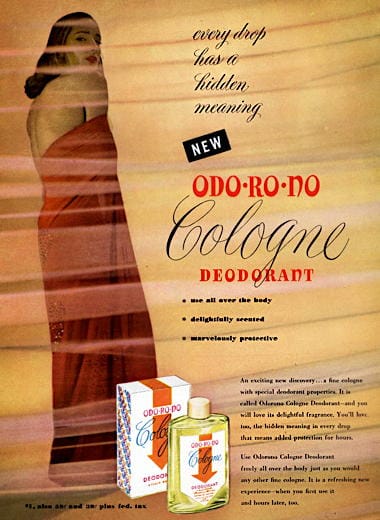

1946 Odo-ro-no Cologne Deodorant.

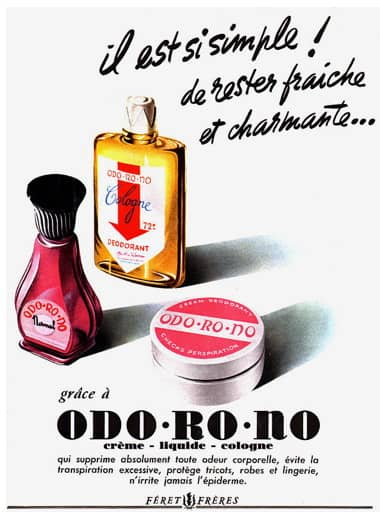

1950 Crème, Liquide and Cologne Odo-ro-no (France). As far as I can tell the cologne was not available in the United States.

1958 Odo-matic (France) equivalent to the Swivel Stick Odo-ro-no sold in the United States.

1958 Cream, Spray, Swivel Stick Odo-ro-no.

1959 Perfumed Odo-ro-no Roll-on (Britain).

1960 Spray, Perfumed Roll-on and Perfumed Instant Stick Odo-ro-no (Britain).