Lipsticks (Part 2)

Continue from: Lipsticks

Lipsticks are made by incorporating colour into a suitable base made of solvents, spreading agents and stiffening ingredients, with a suitable fragrance and preservatives mixed in. Each part of the lipstick formulation – colour, base, and perfume – had problems that needed to be solved by the cosmetic chemists of the day.

Early twentieth century lipsticks were relatively simple mixtures of fats, oils and the pigment carmine.

No. 1516 Carmine, No. 40 100 Soft paraffin—white 550 Spermaceti 300 1000

No. 1517 Carmine 100 Zinc oxide 50 Ceresine 300 Almond oil 50 Soft paraffin—white 500 1000 (Poucher, 1932, p. 471)

Things got more complicated in the 1920s when bromo acids were introduced which required the use of specialist solvents. Initially, materials like stearic acid were employed but, by the 1930s, castor oil was almost universally preferred as the bromo acid solvent. Unfortunately, it was not readily compatible with other ingredients used in lipsticks and this required cosmetic chemists to introduce more complex lipstick formulations.

per cent Spermaceti 31.0 Paraffin 5.0 Cocoa butter 7.0 Cholesterin absorption base 26.0 Castor oil, tasteless 4.0 Benzoinated lard 8.5 Perfume 0.9 Preservative 0.1 Bromo acid 2.5 Butyl stearate 5.0 Color 10.0 (The Manufacturing Chemist, 1935, p. 388)

per cent Absorption base 16.0 Castor oil 22.0 Glyceryl monostearate 20.0 Ceresin 3.0 Beeswax Yellow 12.0 Carnauba 2.0 Ozokerite 1.0 Diethylene Glycol Monostearate 2.0 Bromo acid 2.0 Isopropyl Palmitate 10.0 Color Lakes 10.0 (Keithler, 1955, p. 428)

Qualities

A good quality lipstick should display a number of characteristics: a melting point that is high enough to ensure that it does not soften during the warmer summer months; strength to resist breaking under pressure when the lipstick is applied; plasticity so that it spreads easily and smoothly on the lips; a pleasant taste; smearing and feathering resistance; moisturising and softening properties to protect the lips; and lasting colour that will remain on the lips for a considerable period of time.

Colours

Lipsticks can be coloured with soluble dyes and/or insoluble pigments, the percentages of each determining its indelibility.

Three distinct types of lipsticks are obtainable by the use of “bromo acid”. Types 1 and 2 are perfectly indelible.

The types are as follows:

Type 1. “Bromo acid” is the only coloring matter entering into the composition of the stick. The range of possible tints is, of course, rather small, being limited to the number of “bromo acids” of different tints, and mixtures of them, obtainable in the requisite degree of purity.

Type 2. In contrast with certain solvents, the orange to orange-red colour of “bromo acid” is changed to yellow to orange. The yellow to orange solutions, however, tint the skin pink. Hence, by the use of such solvents, lipsticks of the type commonly called “Tango” can be got, which change colour when applied to the lips.

Type 3. The “bromo acid” is used in conjunction with suitable colouring matters of the pigment type. These sticks are semi-indelible, since the pigment colour tends to come off. Nevertheless, lipsticks of this type enjoy immense popularity, owing perhaps, to the very large number of tints which can be made.(Redgrove, 1935, pp. 123-124)

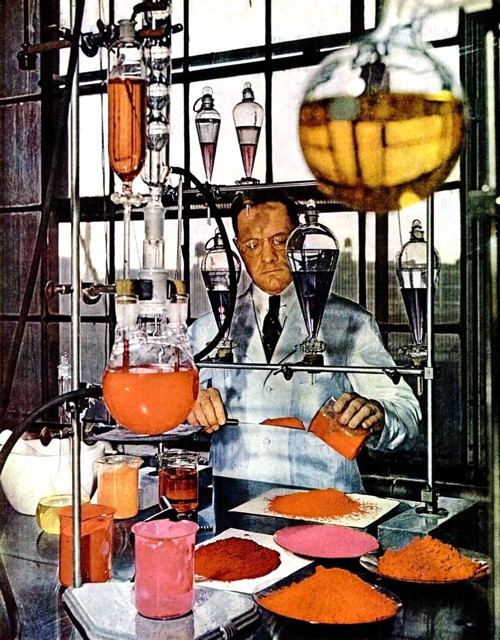

Above: Cosmetic chemist Paul Luffer developing new colour formulations for Tangee lipsticks (LIFE, 1947).

Dyes: Early lipsticks contained natural dyes but from the 1920s onwards synthetic bromo acids were the dyes of choice. They were used alone to produce a ‘natural’ or changeable lipsticks – such as that made by Tangee – but, in general, one or more bromo acid dyes was combined with pigments and formulated so that the stain left on the lips would match the pigment colour visible in the lipstick as closely as possible. Given the limited range of colours in early lipsticks this was not much of a problem but as the number of lipstick shades increased it became more of an issue. The use of bromo acid dyes in lipsticks also meant that most lipsticks that used it were produced in variations of red: blue-red, orange-red or red-red.

See also: Tangee

Pigments: Most coloured pigments used in lipsticks are coal-tar dyes made into lake colours by precipitating the dye onto an insoluble base. In this form the dyes do not stain the lips, so they are easier to remove, but they are not as long lasting. As mentioned previously, early lipsticks came in a limited range of colours so a light-coloured lipstick could be made with cosmetic scarlet lake, a medium-coloured lipstick with cosmetic medium red lake, and a dark-coloured lipstick with maroon lake.

Not all pigments used in lipsticks are insoluble dyes. Inorganic white pigments like zinc oxide and titanium dioxide were used to brighten reds or produce pinks, and iron oxide pigments were added for special effects. When pearlescent lipsticks became popular after the Second World War, the use of fish scales, mica-coated titanium dioxide, bismuth oxychloride (‘synthetic pearl’) and other pearlescent pigments became more common. All these pigments needed to be ground very finely so that they did not produce a gritty feeling when applied to the lips.

See also: Pearl Essence

Many of the colours used in lipstick and other forms of make-up were also used in food so their safety came under increasing scrutiny during the twentieth century. Lipsticks are ‘eaten’ so it is important that the ingredients used in them are not toxic or irritating. In the United States for example, certified lists of colours that could be used in cosmetics (D&C or F,D&C) were published by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and as colours were added to or deleted from this list cosmetic manufacturers made adjustments to their colour recipes.

Lipstick color. Pink. Parts Bromo D&C Orange No. 5 2.0 Color (Not lakes) D&C Red No. 19 6.0 D&C Red No. 37 2.8 D&C Red No. 13 1.0 D&C Yellow No. 11 0.2

Lipstick color. Dark Red. Parts Bromo D&C Red No. 21 1.0 D&C Red No. 24 1.0 Color Lakes D&C Red No. 22 2.0 D&C Red No. 34 Ca Lake 4.0 D&C Red No. 12 Ba Lake 3.3 D&C Orange No. 3 Ba Lake 0.5 D&C Yellow No. 5 Ba Lake 0.2 (Keithler, 1955, p. 429)

Base

As well as being the medium that delivers colour to the lips, the base also supplies the lipstick with its structure. It must be strong enough to resist crumbling or breaking, but soften when used so that the lipstick can slide easily over the lips and apply colour to them. Both of these characteristics are affected by temperature.

The temperature at which a lipstick softens depends primarily on the amount, type, and combination of waxes used in the base. Waxes with a higher melting point give the lipstick greater strength, while those with a lower melting point allow it to soften when it is applied, so a combination of waxes must be used. Fats and oils in the base also affect these qualities as they give a certain degree of plasticity to the lipstick which reduces the possibility of it cracking or crumbling, while providing the lipstick with important emollient (creamy) characteristics.

Over the years a wide variety of substances have been use in formulating lipstick bases including beeswax, candelilla wax, carnauba wax, castor oil, lanolin and lanolin absorption bases, ozokerite, ceresin, cocoa butter, lard, cetyl alcohol, petroleum jelly and liquid paraffin. However, although formulations became increasingly sophisticated, the fundamentals did not change dramatically until silicone derivatives came into widespread use.

Perfume

Lip cosmetics differ from other forms of make-up because they are tasted as well as smelled, so both fragrance and taste need to be considered when selecting a suitable perfume. The need to mask ingredients that have an unpleasant taste – such as lanolin, beeswax, bromo acids and castor oil – means that lipsticks contain higher levels of perfume than other forms of make-up. Amounts of up to 3% were still being recommended in the 1950s (Vasic, 1958), although most authors suggested that 1-2% was sufficient. As with eye cosmetics, not all aromatics were suitable for use, as many irritated the sensitive lip tissue or themselves had a disagreeable taste.

One solution to the problem of lipstick palatability was to include flavours and sweeteners.

A light perfume with a sweet, fruity, subdued flavour is the type normally required for lipsticks. Floral types such as rose, jasmin, orange blossom, and violet are also popular. Lilac, lily-of-the-valley, cyclamen and mimosa are less popular. Hyacinth, narcissus and tuberose are unsuitable. Perfumes of a light, spicy character are also in demand. But the fruity and spicy note must not be overdone and the delicate perfume-flavour balance must be maintained.

(Vasic, 1958, p. 431)

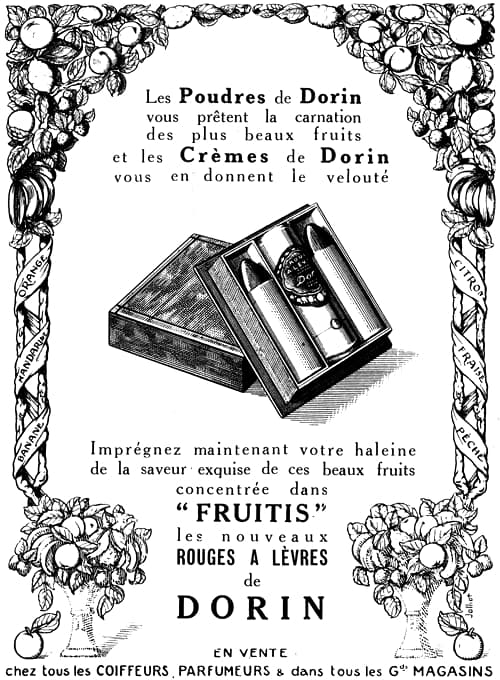

Some lipstick manufacturers discarded any idea of a ‘delicate perfume-flavour balance’ and produced a flavoured lipstick. These go back to the 1920s, the first probably being developed in France. For example, Dorin introduced Fruitis Lipsticks in Banana, Mandarin, Orange, and Lemon flavours in 1922.

Above: 1922, Dorin Fruitis Lipsticks.

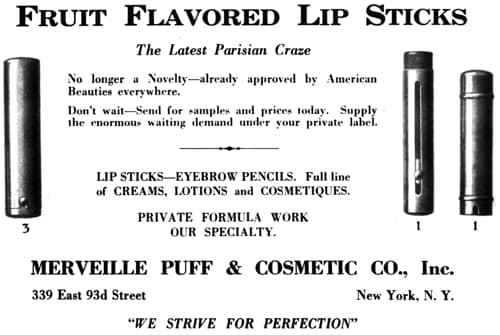

There are also examples from the United States.

Above: 1924 Merveille Fruit Flavored Lipsticks.

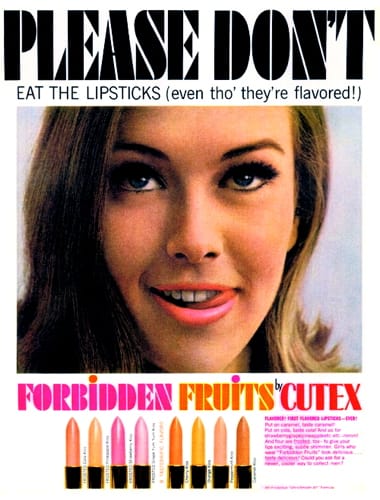

The idea has been revived over the years. Those that I know of are the fruit lipsticks in raspberry, strawberry, pineapple, orange, lemon and lime flavours produced by Rose Laird (1941); Harriet Hubbard Ayer’s Ayerfast (1951), indelible lipsticks in Mint Rose and Clove Carnation flavours; Forbidden Fruits by Cutex (1964), a line of strongly-flavoured lipsticks originally released in caramel, orange, cherry and peppermint; and Bonne Bell’s Lip-Smackers (1973).

Manufacturing lipsticks

For much of the twentieth century the basic procedure for making lipsticks was relatively simple. The ingredients were thoroughly mixed together in a heated liquid state, then poured into moulds to form the lipsticks which, after being cooled, were removed from the moulds, fitted into cases and packaged for sale. Like other cosmetics, the production of lipsticks started out as a cottage industry with most of the work being done by hand. However, as the demand for lipstick increased and batches got larger, the methods used evolved and became increasingly mechanised and systematised. The main issues were to ensure that the colours were uniformly dispersed so streaks and graininess were eliminated and to produce moulded sticks with a smooth, finished appearance.

Manufacturing lipsticks can be divided it into four main steps: colour blending, melting and mixing the ingredients, moulding the lipsticks, and packaging.

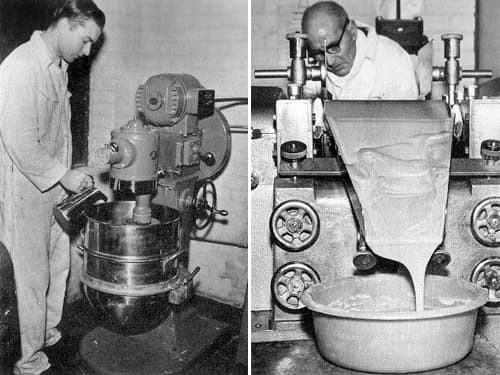

Left: Wetting and mixing pigments. Right: Running the mixed colours through an ointment mill (deNavarre, 1975).

Colour blending: For much of the twentieth century both dyes and pigments were used. The pigments were measured out, sifted and mixed with enough oil to enable them to be made into a paste. Unfortunately, no matter how finely ground the pigment particles were, they tend to clump together in the mix giving it a grainy appearance. Manufacturers making lipsticks largely by hand could remove the lumps by passing the mixture through a fine sieve several times until it was smooth, but a better solution was to run the pigment mixture repeatedly through a paint or ointment mill until an even texture was achieved. If a dye like bromo acid was used in the lipstick it would normally be dissolved in a suitable solvent – in a separate heated container – before being added to the rest of the mixture. Lipsticks made with dyes as the only colourant would not have required the use an ointment mill.

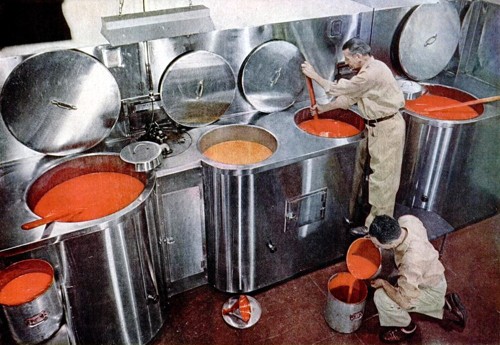

Mixing the ingredients: The main ingredients making up the lipstick base were heated in separate metal containers made from stainless steel or enamel. Some manufactures heated the fats and alcohols in one container and the waxes in another, while others heated all three sets of ingredients separately. Temperature consistency was achieved by having the vessels water-heated. Once the correct temperature was reached, the colour was added to the oils and alcohol, and slowly mixed until it was evenly incorporated. Slow mechanical stirring of the mixture also helped to remove any small air bubbles present in the mixture so that they did not get moulded into the finished lipsticks. To help in the removal of these air bubbles later manufacturers began to enclose the mixing vessel so that they could generate a partial vacuum to help draw the air bubbles out.

Above: Mixing lipsticks in a Tangee factory (LIFE, 1947).

After several hours of slow mixing the pigmented mass was then combined with the hot wax and further mixed until uniform. Manufacturers might then pass the mixture through an ointment mill to ensure that all the ingredients were uniformly dispersed.

Best products result from milling the finished salve through an ointment mill, and then gently remelting to fill out the moulds. Where this is not possible the colours should be ground thoroughly to a cream with part of the oils in a mortar, and passed through fine muslin, several times if necessary until perfectly smooth; then add the desired perfumed oil to the colour in a nicely warmed mortar, and follow with the strained wax and oil mixture, gradually, at a gentle temperature, just high enough for subsequently running into the moulds.

(P&EOR, 1927, p. 422)

The last ingredients to be added to the mix were generally the preservatives and perfumes. To reduce the possibility of the volatile perfume evaporating, the mixture was allowed to cool slightly before the perfume was added.

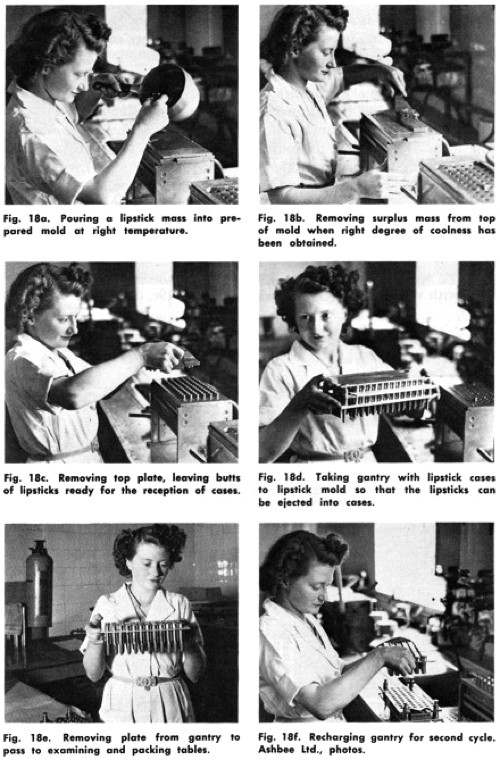

Moulding the lipsticks: When the completed lipstick mass was ready, it was poured into moulds made to fit the size and shape of the lipstick case specified by the manufacturer. The pouring temperature had to be carefully controlled to avoid the colourant separating or having moulding blemishes, air bubbles and other artifacts being introduced into the finished sticks.

Above: Hand moulding lipsticks (deNavarre, 1975).

The lipsticks contracted on cooling in the moulds and were removed after an hour or so. This time was dramatically reduced by refrigerating the mould, a practice that became a standard procedure in larger manufacturing concerns. Chilling the sticks also had the added benefit of reducing the tendency of the lipstick to sweat or bloom while cooling.

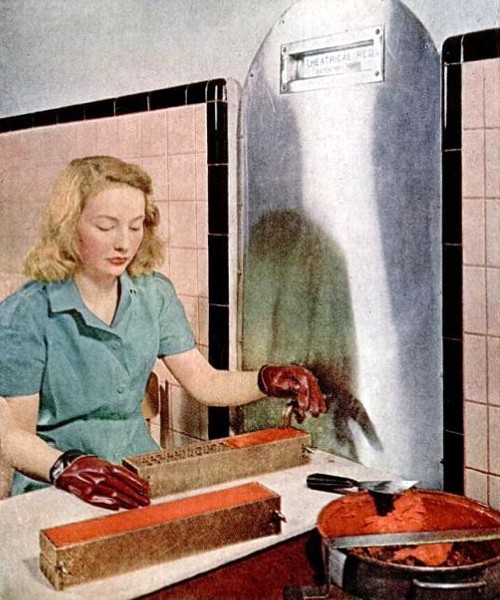

Above: Filling lipstick moulds in the Tangee factory. The tap on the right is connected to a tank containing molten mixture. Gloves are worn to prevent the hands getting accidentally burned (LIFE, 1947).

Above: Removing lipsticks from moulds in the Tangee factory so that they can be inserted into cases (LIFE, 1947).

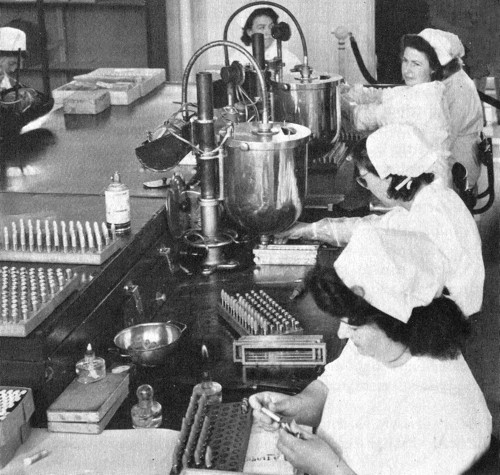

Once removed from the moulds, the sticks were placed in their casings and then checked for moulding ridges and air bubbles. If these were found they could be smoothed out by passing the lipstick briefly through a low-intensity spirit or gas burner flame and then smoothing the surface with the fingers or a spatula.

Above: Lipstick moulding and assembling at Lancôme, Paris. Note the heated metal containers used to fill the moulds and the small spirit lamps needed to flame the finished lipsticks if they showed blemishes (deNavarre, 1975).

The process of making lipstick in this manner was very labour intensive. From the 1970s onwards, automatic moulding machines began to be used which enabled manufacturers to deliver higher volumes of lipsticks without increasing labour costs. Manufacturers also began to experiment with moulds made of silicone or high temperature plastics and these have now replaced the traditional metal moulds in many situations.

Above: Checking finished Tangee lipsticks and adding their tops. The shade on the right is Natural (LIFE, 1947).

Using lipstick

Applying lipstick has changed over the years. There are suggestions that early on many women smoothed lipstick over their mouth with their finger which would mean that the widespread practice of applying it directly across the lips was a later development. I also note that some make-up professionals such as Jack Dawn [1892-1961] were still recommending that lipstick be applied with a finger well into the 1930s.

Don’t apply lip-rouge with your stick. Apply it with your little finger.

(Jack Dawn quoted in Movie Classic, December, 1935)

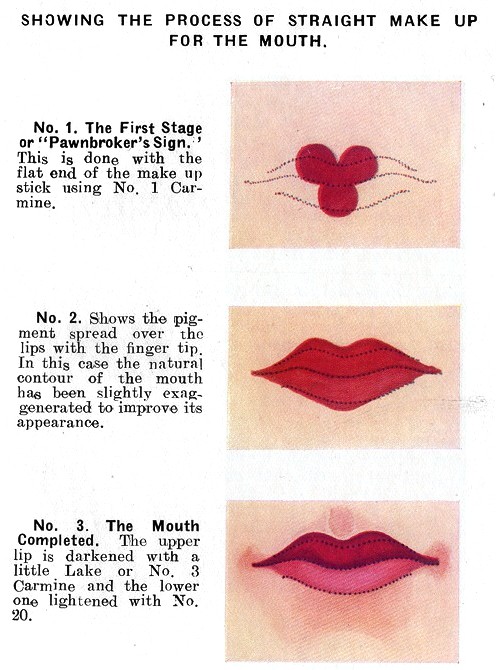

A common way to use a finger to apply lipstick was the three-dot method. The idea probably came from theatre/movie make-up techniques and helped make a perfect cupid’s bow. It may also have been very useful when using lipsticks that were more likely to break than those available today.

Above: Straight mouth make-up (Ward, 1937).

This piece of beauty advice from the 1930s follows this idea:

Take the lipstick and apply a very little colour to the tip of the first finger, and then transfer this to the lips. It should be put on in three dots. One at each side of the “cupid’s bow” on the upper lip and one immediately below and in the centre of the lower lip. Thus you have three circles of colour. Then while the mouth is stretched, run the finger along just inside the lips, smoothing out the colour to the desired shape. There should be a little colour just inside the mouth as well as actually upon that part of the lips which can normally be seen.

(Sloane, 1933, p. 12)

Movie make-up artists generally switched to using a brush to apply lipstick as this gave them greater control. The practice was adopted by many women when companies like Max Factor and Revlon promoted it and made lip brushes generally available.

Above: Perc Westmore [1904-1970] using a lipstick brush on Ann Dvorak [1911-1979].

Fashions in mouth shapes have also come and gone over the years and lipstick has played its part in these changes, as the move from the small cupid’s bow lips of the 1920s to the wide hunter’s bow shape of the 1930s clearly demonstrates. Although fashion changes in mouth shape have not completely disappeared they are less important today, with make-up artists being more concerned with correcting perceived deficiencies in the shape of the lips than anything else. Lipstick can make lips appear larger, look thicker, lift corners and correct unevenness, issues that have been of concern to women for some time.

First Posted: 30th October 2013

Last Update: 7th April 2022

Sources

The American perfumer & essential oil review. (1937). New York: Robbins Perfumer Co.

Anonis, D. P. (1974). Perfumes and lipsticks. The Drug and Cosmetic Industry. June, 34-37 & 134-135.

Birge, W. S. (1915). My lady’s handbook. Health, strength, and beauty. New York: Sully and Kleinteich.

Chilson, F. (1934). Modern cosmetics. New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

Courtenay, F. (1922). Physical beauty. How to develop and preserve it. New York: Social Cultural Publications.

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston: D. Van Nostrand Company.

deNavarre, M. G. (1975). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd ed., Vols. IV). Orlando: Continental Press.

Gattefossé, R. M. (1959). Formulary of perfumes and cosmetics. (Trans.). New York: Chemical Publishing Co., Inc.

Hetherington, M. (2015, December 16). Maurice Levy – The man who never invented metal lipstick containers. Retrieved January 6, 2016 from http://collectingvintagecompacts.blogspot.com.au

Keithler, W. R. (1955). Lipsticks. Drug & Cosmetic Industry. 76 (3) March, 55, 330-331 & 425-429.

LIFE (1947). New York: Time, Inc.

Lipsticks. (1927). The Perfumery and Essential Oil Record. October, 421-422.

The manufacturing chemist. (1935). London: Miller Freeman.

New sales approach to cosmetic containers. (1957). Drug & Cosmetic Industry. 81 (1) July, 55, 126.

Piesse, G. W. S. (1857). The art of perfumery, and the method of obtaining the odors of plants, with instructions for the manufacture of perfumes for the handkerchief, scented powders, odorous vinegars, dentifrices, pomatums, cosmetiques, perfumed soap, etc. with an appendix on the colors of flowers, artificial fruit essences, etc. etc. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston.

Poucher, W. A. (1926). Eve’s beauty secrets. London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd.

Poucher, W. A. (1932). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (4th ed., Vols. 1-2). London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd.

Redgrove, H. S. (1935). A note on lipstick manufacture. The Manufacturing Chemist. April, 123-124.

Sagarin, E. (Ed.). (1957). Cosmetics: Science and technology. New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc.

Sloane. (1933). Teach your clients the correct use of lipstick. The Hairdresser and Beauty Trade. December, 12.

The toilette of health, beauty, and fashion. (1834). Boston: Allen and Ticknor.

Vasic, V. (1958). Perfumes for cosmetics. 3. Lipsticks. Manufacturing Chemist. October, 431-432.

Waggoner, W. C. (Ed.). (1990). Clinical safety and efficacy testing of cosmetics. New York: M. Dekker.

Ward, E. (1937). A book of make-up. London: Samuel French Ltd.

1946 Dana Tabu Indelible Lipstick.

1946 Solitair Fashion Point Lipstick.

1945 Floress fluorescent lipsticks.

1947 Revlon ‘Matching Fingertips and Lips’.

1947 Chen Yu lipsticks and matching nail polish.

1947 Prince Matchabelli Automatic Lipstick.

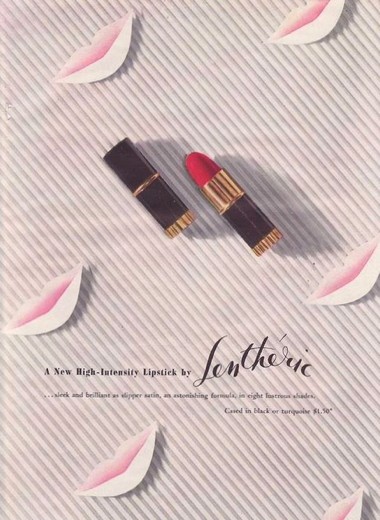

1947 Lenthéric Lipsticks.

1948 Revlon Lip-Fashion, a longer style lipstick.

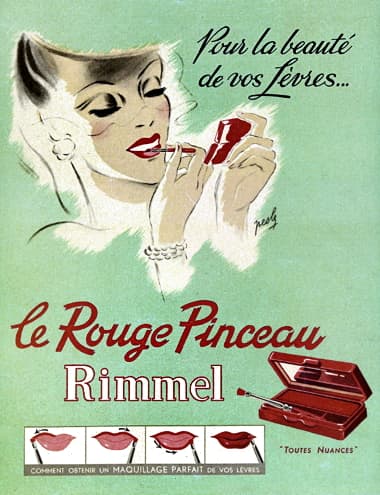

1948 Rimmel Rouge Pinceau. Sold in a case reminiscent of a cake mascara, a brush was used to outline and fill in the lips with rouge.

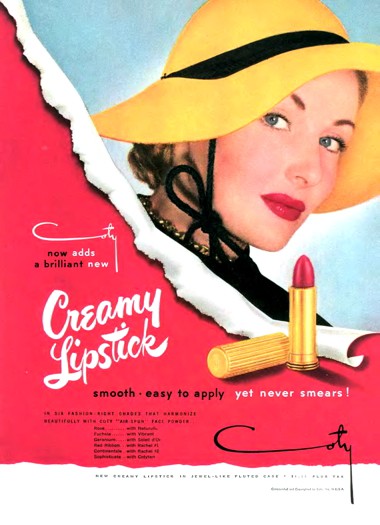

1949 Coty Creamy Lipstick.

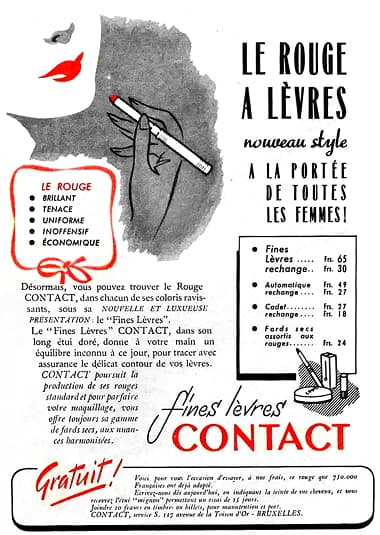

1949 Contact lipsticks (France).

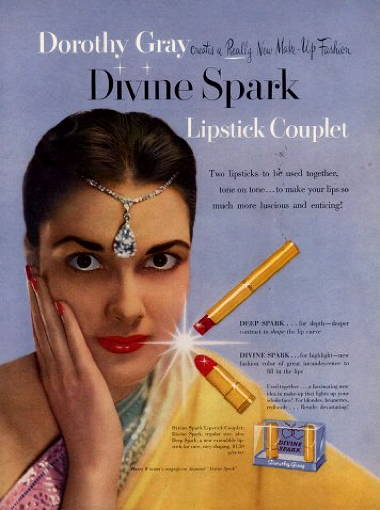

1949 Dorothy Gray Lipstick Couplet: Deep Spark and Divine Spark lipsticks.

1950 Gala of London Interchange.

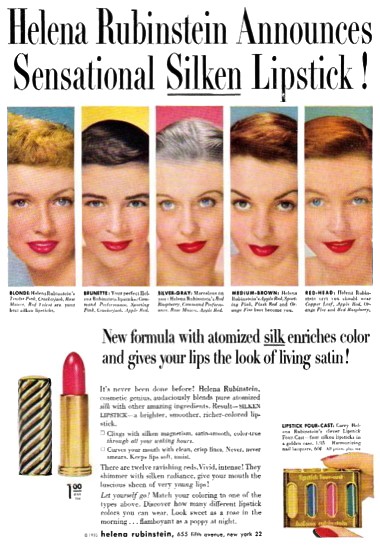

1950 Helena Rubinstein Silken Lipstick made with powdered silk that had been dyed with bromo acids that stained the lips and coloured the lipstick itself. The strong affinity silk had with the bromo acids enabled the lipstick to dispense with the usual bromo acid solvents like castor oil.

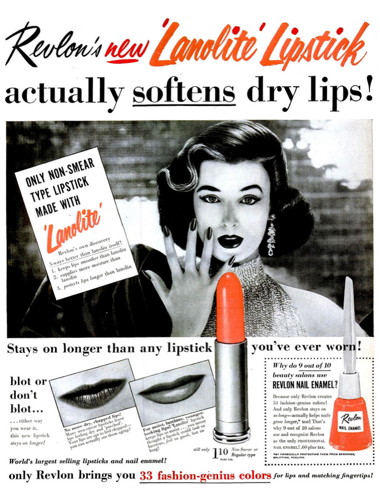

1954 Revlon Lanolite Lipstick in 33 Fashion Shades. In 1954 Revlon was in the middle of the ‘lipstick wars’ primarily with Hazel Bishop and Coty. The lipstick contained a form of lanolin, a common ingredient used in lipsticks to help offset the drying effect of the bromo acid dyes. Production of the lipstick stopped a few years later.

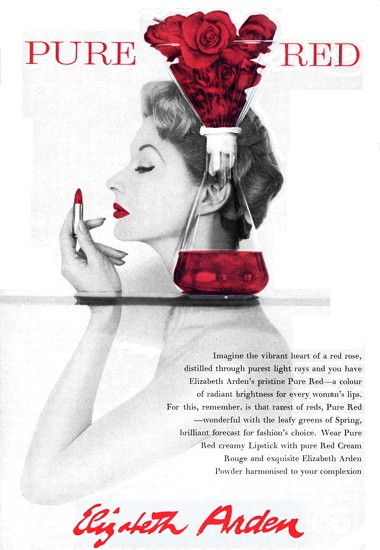

1955 Elizabeth Arden Lipstick in Pure Red shade.

1955 Tangee lipsticks in a range of sizes and prices from 15 cents through to US$1.00.

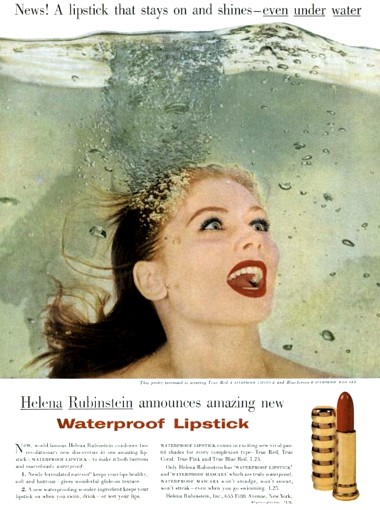

1956 Helena Rubinstein Waterproof Lipstick in a ‘Wedding Ring’ case.

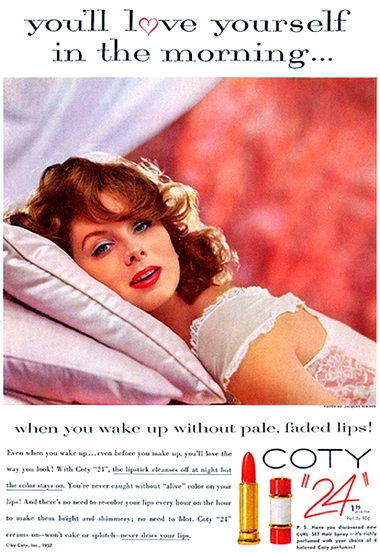

1957 Coty “24”. This indelible lipstick challenged Revlon for a time.

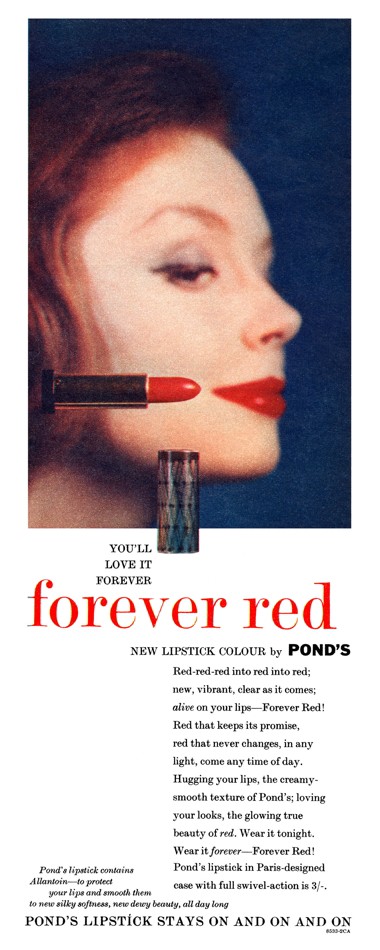

1959 Pond’s Forever Red.

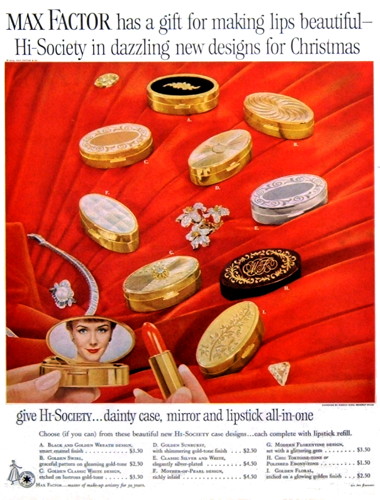

1959 Max Factor’s Hi-Society lipstick cases. This compact was Max Factor’s answer to the designer lipstick cases put out earlier in the decade by other manufacturers. First released in 1959, the mirrored cases were made in metal and plastic and included a small, replaceable lipstick. They sold for range of prices depending on the quality of the case.

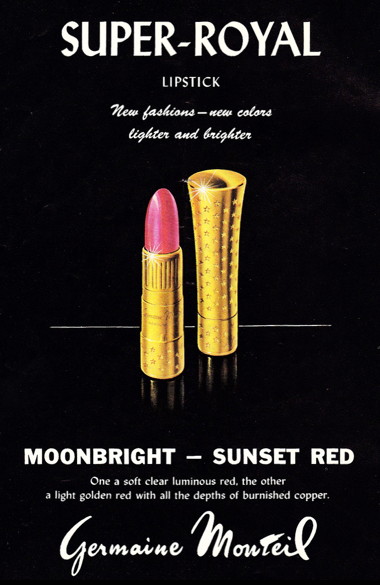

1959 Germaine Monteil Super-Royal Lipstick made with Royal Jelly in Moonbright and Sunset Red shades

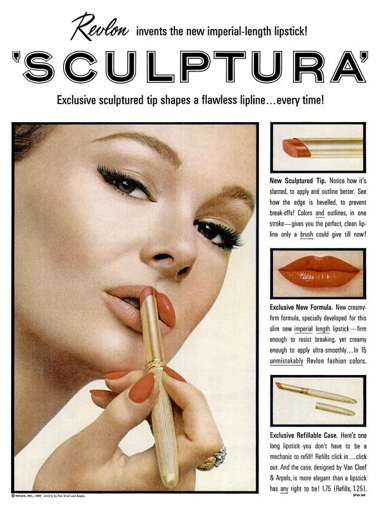

1963 Revlon Sculptura Lipstick.

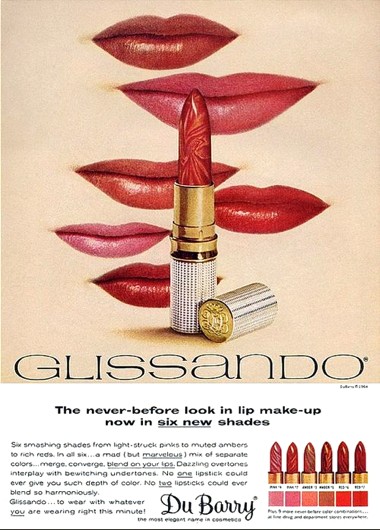

1964 Du Barry Glissando lipsticks by Richard Hudnut.

1964 Cutex Forbidden Fruits. Originally launched in caramel, orange, cherry and peppermint but when they proved to be successful other flavours were quickly added.

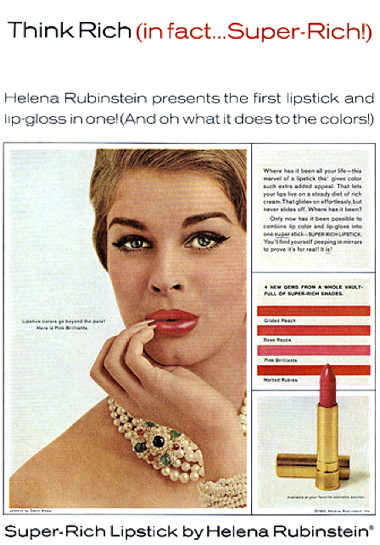

1965 Helena Rubinstein Super-Rich Lipstick. A reflection of the move in the 1960s to creamier lipsticks.

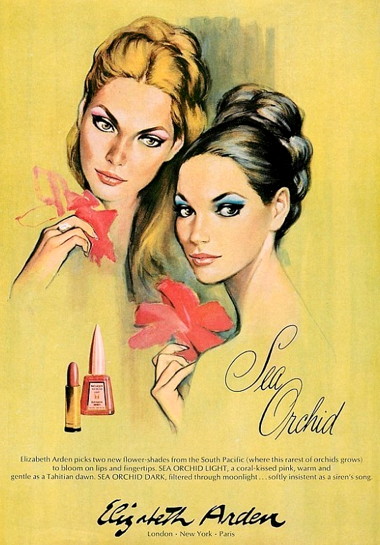

1966 Elizabeth Arden Lipstick and nail polish in matching Light and Dark Sea Orchid shades.

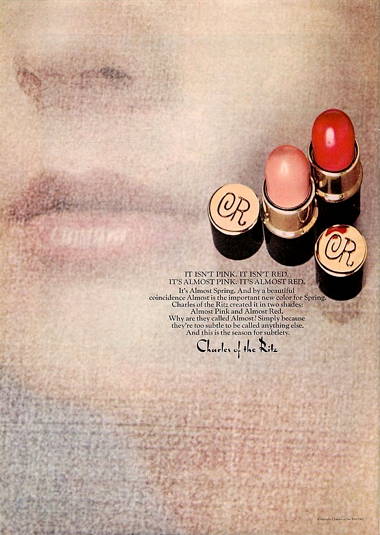

1967 Charles of the Ritz lipsticks.

1968 Gala Lipsticks with a soft core.

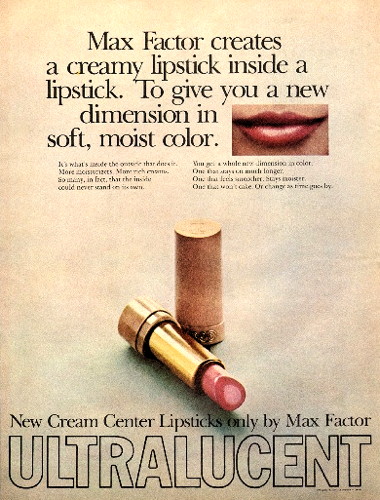

1969 Max Factor Ultralucent Cream Center Lipstick. The lipstick had a firmer exterior but softer interior and was an attempt to avoid one of the common problems of the creamier lipsticks of the time, their tendency to break.