Lipsticks

Continue onto: Lipsticks (Part 2)

Chapped and cracked lips caused by the dry air that comes with hot, dry summers or freezing cold winters produced a range of products to ameliorate the problem. In the nineteenth century, soothing and protecting lip-salves or lip pomades could be purchased from a local pharmacist or druggist, or made up at home using one of a number of available recipes. Some contained a red colouring agent – such as alkanet or black grape juice – which also reddened the lips and made them more attractive.

A Scarlet Lip-Salve.

Take an ounce of the oil of sweet almonds, cold drawn; a drachm of fresh mutton suet; and a little bruised alkanet root; and simmer the whole together in an earthen pipkin. Instead of the oil of sweet almonds, you may use oil of jasmin, or oil of any other flower, if you intend the lip-salve to have a fragrant odour.(The toilette of health, beauty, and fashion, 1834, p. 87)

Rouge

A nineteenth-century alternative to a coloured lip-salve was to beautify the lips with a liquid or paste rouge. For example, Bloom of Roses – a liquid rouge made from carmine dissolved in ammonia and rose water – was used to redden cheeks but some women also applied it to their lips, a practice that continued into the twentieth century.

Bloom of roses

Strong liquid ammonia ½ oz. Finest carmine ¼ oz. Rose-water 1 pint. Extract of rose (triple) ½ oz. Place the carmine into a pint bottle, and pour on it the ammonia; allow them to remain together, with occasional agitation, for two days; then add the rose-water and esprit, and well mix. Place the bottle in a quiet situation for a week; any precipitate of impurities from the carmine will subside; the supernatant “Bloom of Roses” is then to be bottled for sale.

(Piesse, 1857, p. 236)

Commercial versions of Bloom of Roses were available throughout the nineteenth century, a popular English form being made by Pears.

PEARS’s [sic] LIQUID BLOOM of ROSES gives a most delightful tinge to the Female Countenance, and to such a degree of perfection, that it may with propriety be said that Art was never so successfully employed in improving the Charms of Nature.

(Pears’ advertisement, 1807)

See also: Rouge

Guerlain

Pears’ Bloom of Roses was one of a number of cosmetics imported from England by Pierre-François-Pascal Guerlain [1798-1864] when he opened his perfume shop on the ground floor of the Hôtel Meurice – a popular residence for English visitors – in Paris in 1828.

By the 1840s, Guerlain was well established, making and selling his own cosmetics including some that were designed specifically for the lips – Roselip, a tinted lip-balm and Extrait de Roses, a liquid lip-rouge. Then, in 1870, he introduced Ne M’oubliez Pas, widely credited as being the first stick lip-rouge (rouge à lèvres en bâton).

Stick cosmetics

Stick cosmetics were well known to the perfumery and pharmacy trades in the nineteenth century and many medicinals and cosmetic were produced in this form; examples being moustache wax sticks and suppositories.

See also: Water Cosmetique (Mascaro)

Coloured lip-salves were generally made as pastes but stick forms could be produced by adding a stiffening agent such as white wax. According to some sources, lip-salves of this type were in existence before 1840.

The following well-tried example, dating from before the “forties” of the previous century is often quoted to-day as new. White wax 2½ ozs., spermaceti 3 ozs., almond oil 7 ozs., balsam Peru 1 dram, alkanet root 1½ ozs., melted together to desired colour, strained, and perfumed if desired.

(Lipsticks, 1927, p. 421)

Lip-salve-sticks and rouge-sticks had some advantages over other forms of lip-rouge; they did not spill like liquid lip-rouges and, if used directly on the lips, did not result in the messy fingers acquired when using a paste lip balm.

The difference between a coloured lip-salve-stick and a rouge-stick or lip-stick is arbitrary but can perhaps be distinguished by the type and the amount of colouring agent used. Lip-salves generally had less colouring and were usually made with cheaper alkanet, while lip-rouges or lip-sticks had more colouring and often used the more expensive carmine. The colouring agent could affect the product’s opacity. Alkanet lip-salves were generally translucent, as the colour was dissolved in the base, whereas lip-sticks containing carmine were usually opaque.

Rose lip salves are usually of weak colour; from ¼ to ½ percent. of lake or pigment or sufficient alkanet root to produce the desired tint. …

Rouge sticks are more heavily coloured, generally with carmine of various grades or the carmine lakes which may be obtained in varying tints—geranium, purple, crimson, carmine, etc.; 5 to 10 per cent. is the usual amount, but it is often increased to as much as 20 per cent.(P&EOR, 1927, p. 422)

Greasepaint

The 1870s also saw the introduction of another stick cosmetic of importance to the story of lipsticks. This was greasepaint, a theatrical make-up sold in sticks wrapped in decorative paper or tin foil.

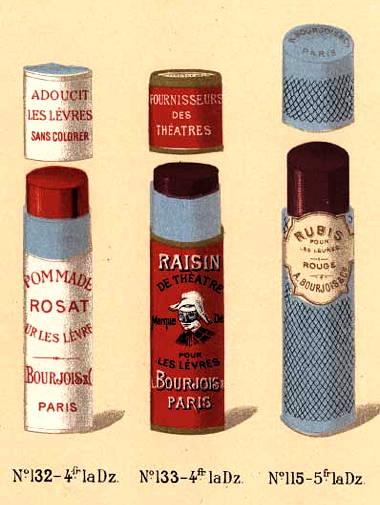

After Ludwig Leichner [1836-1912] began selling greasepaint in 1873, a number of French companies supplying the French theatrical trade with powdered make-up also began to include greasepaint sticks (batons grime) in their make-up lines. For example, A. Bourjois et Cie. sold greasepaint labeled as ‘Batons Extra-Fins’ from the 1880s at the latest. Like the powders, some of these greasepaint sticks found other cosmetic uses away from the theatre.

See also: Greasepaint and Leichner

The use of powder, rouge and other ‘paints’ became more acceptable towards the end of the nineteenth century, some French firms already producing theatrical make-up to begin selling their wares, including batons grime, more widely. Paris led the way in the use of make-up in the late nineteenth century and as French fashion spread to other parts of the world, French cosmetics did so as well.

In Paris artificial complexions have become so general that a woman has no more hesitation about displaying a rouge pot than a powder puff. In London it is very much the same thing now, and among the jewelled trinkets which women carry in their pockets there is generally one containing an eyebrow pencil or a stick of lip salve.

(Auckland Star, 1901, p. 1)

Lipstick cases

At some stage lip-rouge-sticks were encased in metal tubes. Cardboard or paper provided protection, portability, and ease of use, but the use of metal allowed for the development of better mechanisms for pushing the stick out of its container and gave the finished product an appeal that would eventually make it an essential item for almost every woman.

Exactly when the first lip-stick was encased in a metal tube is unknown and is likely to remain so for a number of reasons. First, there is the question of the distinction between a lip-salve and a lip-stick with it being very likely that some lip-salves were sold in metal containers. Second, society women who wanted something a little more substantial than paper or cardboard to hold their lip-salve or lip-stick could order a metal container from a jeweller. Cheaper ready-made metal cases were also available for purchase from department stores and other outlets. Victorian women could add these cases to other items in their chatelaine.

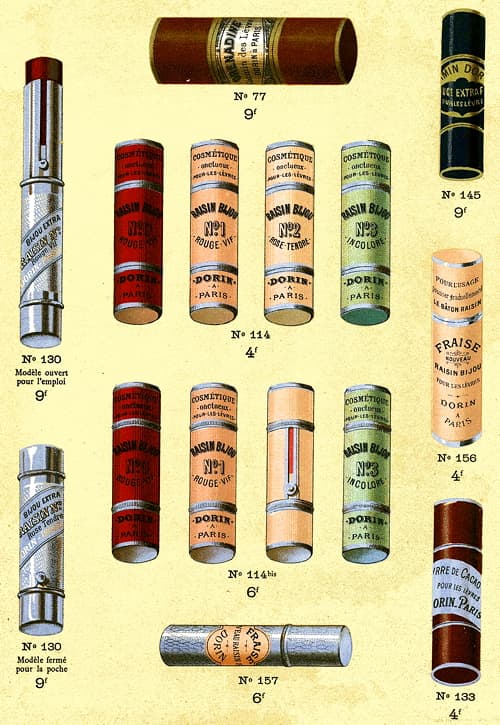

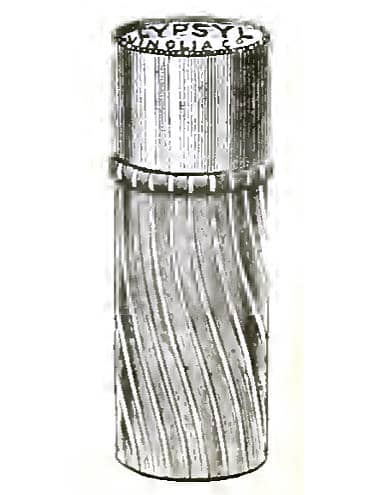

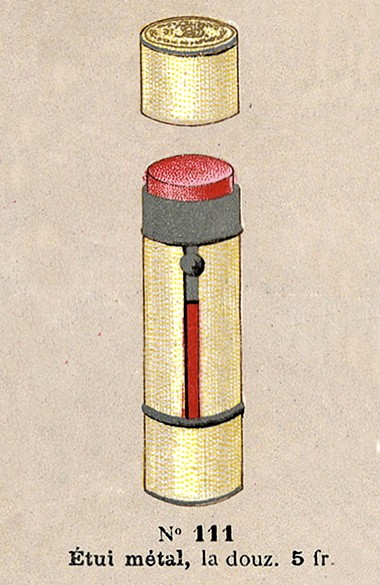

The first lip cosmetics sold in metal cases, that I can date with some precision, are from the 1890s. Vinolia Lypsyl made by the British company Blondeau et Cie; later known as the Vinolia Company was available in a metal tube no later than 1892 and a Dorin catalogue from 1893 includes lipsticks in nickel cases. However, it seems likely that French-made metal lipstick cases were being produced earlier than this.

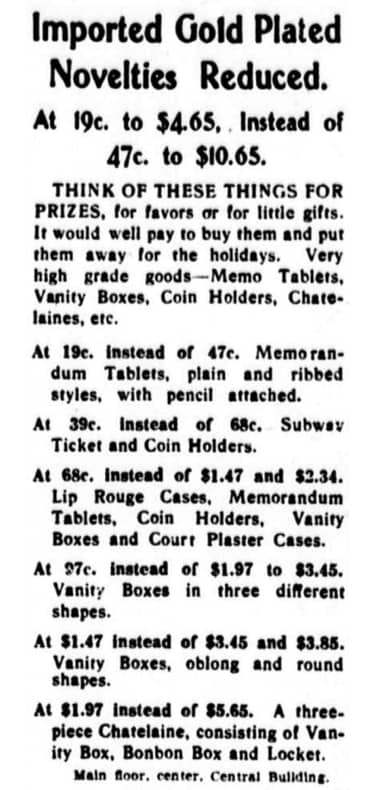

Above: 1893 Dorin Lipsticks (rouges à levres).

The first American lipstick sold in a metal case is generally credited to the Scovill Manufacturing Company (Connecticut, U.S.A.) in 1915 and this case is often erroneously credited as being the first metal lipstick case.

The modern lipstick can be said to have been the result of a meeting in New York in 1915 between Anthony Guash, a French cosmetics manufacturer and Maurice Levy, an American investor. Their meeting had been arranged by an official of the Scovill Manufacturing Company and resulted in the formation of the French Cosmetic Manufacturing Company.

(D&CI, 1957, p. 55)

There are suggestions that this was not even the first American metal lipstick case made by Scoville as it had previously produced a metal lipstick container for the Luxor Company of Chicago in 1914 (Hetherington, 2015). It would not surprise me if earlier American versions are later unearthed, given the occasional description in American newspapers of earlier products. The one below from 1913 appears to be a stick lip cosmetic sold in a metal case that could be added to a chatelaine.

Lip Pomade

The frosty atmosphere makes the tiny metal cases of lip pomade especially desirable for my lady’s hand bag, for just a touch of cold cream protects the lips from the dryness of the wind. The metal cases are about two inches long, and are gilt, finished at the top with an imitation jewel and a ring by which they may be attached to a chain. They are about half an inch in circumference. The pomade is slightly tinted, either flesh or rouge color, so that its use cannot be detected, or, for those who so wish, it may be had in white. These are priced at less than one dollar.(Daily East Oregonian, February 21, 1913)

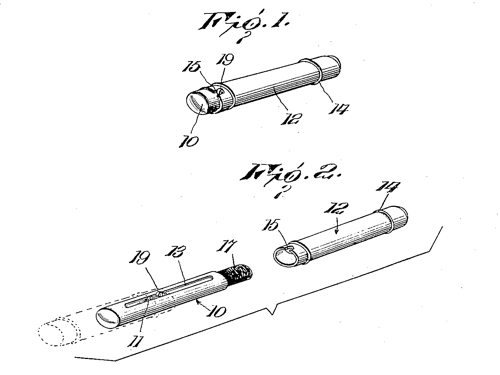

The first American patent for a metal lipstick holder goes to William Kendall.

Above: 1917 Drawings from an American patent taken out by William Kendall for a lipstick case (US1236846, 1917).

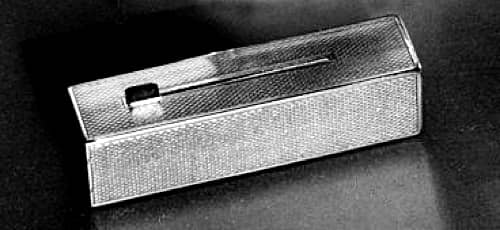

Once introduced, metal soon became the lipstick container of choice, particularly after the First World War when scrap metal was abundant and metal prices were low. Early forms were generally small, often oval in cross-section rather than round, and used some form of sliding mechanism to extend and then withdraw the stick. Some had a paper label glued to the case while others had the company name embossed into the metal. These glued-on paper labels soon disappeared except for the one applied to the base of the lipstick case to indicate the lipstick shade.

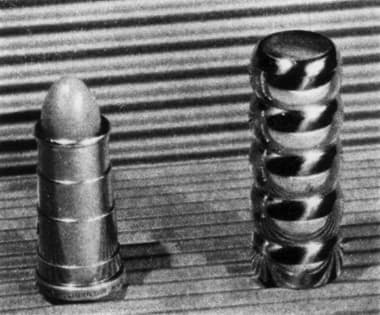

Above: An early brass lipstick case showing the sliding mechanism used to push the lipstick out of the tube. The oval shape of the tube made it easier to fit the cap on correctly.

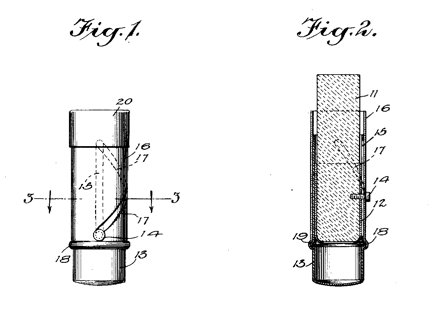

An early modification of the push-up type was the double which had a sliding grove curved around the lipstick case. This mechanism required the lipstick tube to be round rather than oval, a situation reinforced by the introduction of lipsticks that used swivel bases from the 1920s onwards.

Above: 1924 Drawings from an American patent taken out by William Kendall for a lipstick with a double mechanism used by the Scovill Manufacturing Company (US1,480,449, 1924). On occasion the pins would dislodge from the groove causing the mechanism to freeze.

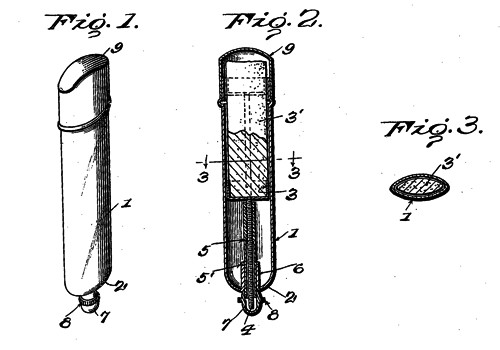

The earliest known patent for a lipstick with swivel mechanism was granted to James Bruce Mason Jr. of Nashville, Tennessee in 1923.

Above: 1923 Drawings from an American patent taken out by James Bruce Mason Jr. (US1,470,994, 1923). The case was oval in cross-section like the early push-up types as the lipstick did not need to rotate.

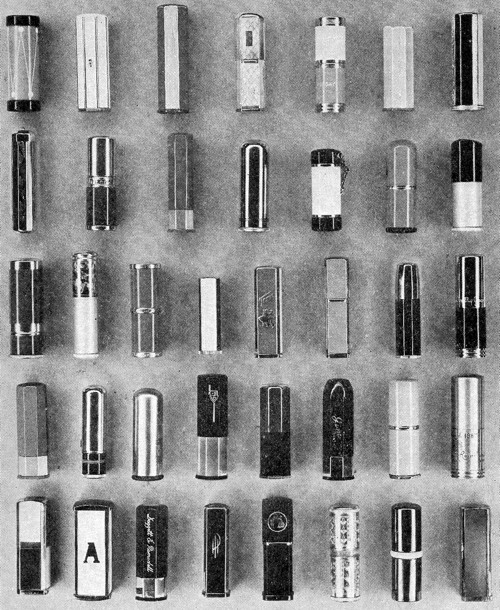

By the late 1920s there were a wide variety of case designs, made from a range of materials, with varying mechanisms for getting the lipstick in and out of the tube. Some, like those from Kissproof, were highly decorated.

The containers vary from nickel plated brass and aluminium to jewelled works of art. There are rich designs in burnt aluminium and in silver of exquisite colour and finish; doubles, in which the slide moves both ways; swivel type; flat ovals and those with hinged caps to prevent loss at the top. America is foremost in their production, followed by Germany and then France.

(Lipsticks, 1927, p. 421)

Above: A range of lipstick cases from the 1930s made by the Bridgeport Metal Goods Manufacturing Company. Lipstick manufacturers could use standard cases, or take undecorated standard cases and have them embellished in a design of their choosing. If they elected for non-standard cases they would have to pay for the metal dies and deal with all the risks associated with changes in fashion.

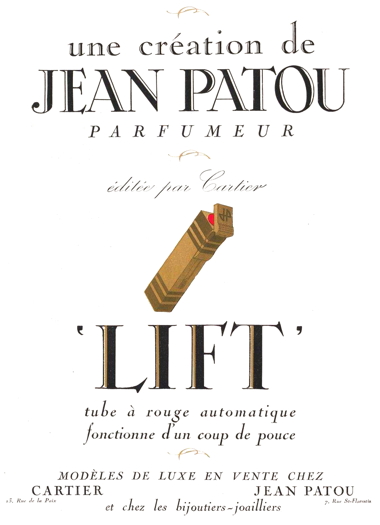

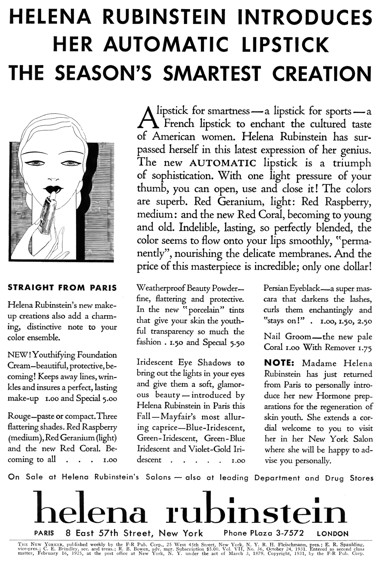

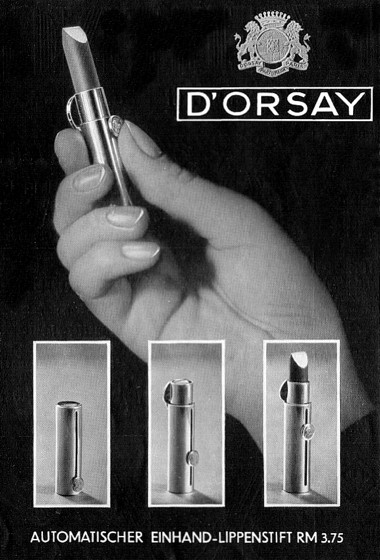

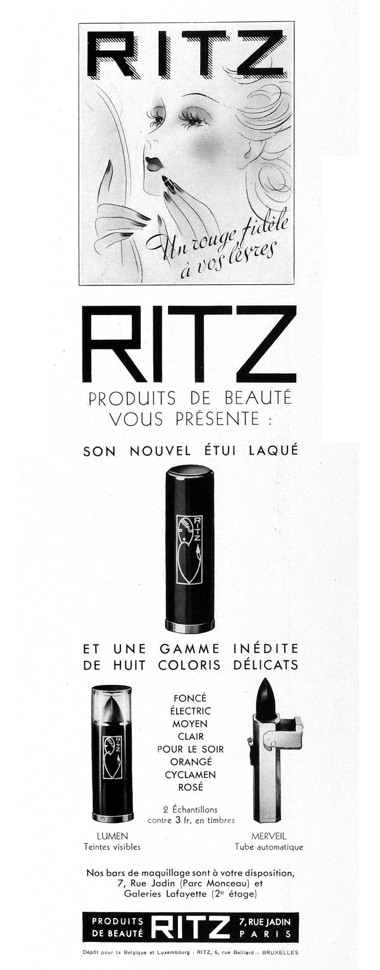

One development from the 1930s were cases that could be opened, used and closed with one hand. Interest in these ‘automatic lipsticks’ was widespread with examples including: Helena Rubinstein’s Automatic Lipstick (1931) and Golden Automatic (1935); Harriet Hubbard Ayer’s Automatic Lipstick (1933); Elizabeth Arden’s Automatic Lipstick (1934); Scovill’s Roll Top Lipstick cases (1934); and Guerlain’s Rouge Automatique (1936).

Above: 1934 Elizabeth Arden Automatic Lipstick. Like most automatics it was a square push-up.

Most automatic lipsticks went out of production during the packaging restrictions imposed during the Second World War and, with a few exceptions such as Hazel Bishop’s Ultra-Matic, Prince Matchabelli’s Automatic Lipstick and Guerlain’s recent Automatic Lipstick, they were not revived. There have been other experiments with lipstick cases – e.g., combining them with mirrors – but most were novelties and not long lasting.

The metal shortages of the Second World War saw lipstick manufacturers switch back to cardboard or use some of the newer plastics for their containers.

Above: 1943 Revlon wartime plastic lipstick case.

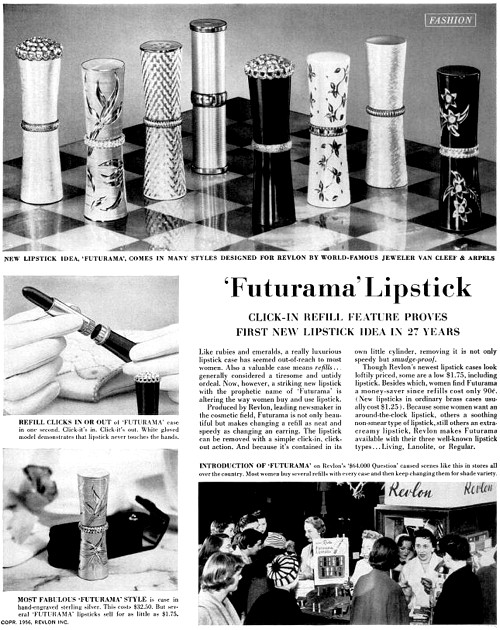

The mechanisms in these substitute cases were often unsatisfactory and after trying them many women resurrected their old metal cases and began transferring sticks into them. This was not an easy matter and the lipstick often broke in the process. To avoid this, some women asked a salesgirl on the cosmetic counter to do the replacement. The easy-to-fit refills introduced after the war that ‘clicked out and in’ made the process a lot easier.

Component standarisation

A major advance in the production of metal lipstick cases came in the 1950s when case manufacturers introduced component standardisation. Breaking down the pieces of a case into its various parts – the base assembly, holder cup and cap – and then manufacturing variations of each at standard sizes, enabled components to be interchangeable. Cosmetic companies could select items from a range of component parts and combine them to produce a lipstick case that suited their particular needs, dramatically reducing fitting costs. They could also pay extra to have one or more of the components made to their specific design with the understanding that they would still fit with other ‘off the shelf’ pieces.

Some of the most impressive metal lipstick cases were made during the 1950s with many using semi-precious metals and gemstones, a practice that would normally be done by a jeweller. The rising post-war prosperity, a general increase in the base price most women paid for lipsticks, the development of component manufacturing, and the 1950s American ‘lipstick wars’ between Hazel Bishop, Coty, Revlon and others, all contributed to this fashion trend.

See also: Lipstick Wars

A good example of cases from this period was Revlon’s Futurama range introduced in 1955. These refillable lipsticks were designed by Van Cleef & Arpel, a Fifth Avenue jeweller. Base models – which included a lipstick in Revlon’s Living, Lanolite or Regular formulation – retailed for as low as US$1.75 in the United States while those made in sterling silver went for as high as US$32.50. Women who wanted something even more exclusive could also go to Van Cleef & Arpel and have a case made in gold and other expensive materials fitted with a Revlon lipstick cartridge.

Above: 1956 Advertorial on Revlon’s Futurama lipsticks.

In 1957, Helena Rubinstein introduced her range of high-quality, refillable, lipstick cases and entered into an agreement with Revlon to fix the price of the lipstick refills. Both companies were later charged by the American Federal Trade Commission (FTC) with conspiracy (AP&EOR, 1958).

Above: 1957 Helena Rubinstein Convertible Lipstick Cases.

The high-quality cases of this period all used easy to fit refills that just clicked out and in.

Above: 1956 Futurama click-in refills.

Unfortunately, they all suffered from the same problem that had plagued metal lipsticks from the beginning; unless protected, the cases collected unsightly abrasion marks when they collided with the other clutter in a women’s purse or handbag and soon looked worn and tired.

Above: A range of metal lipstick cases showing signs of wear.

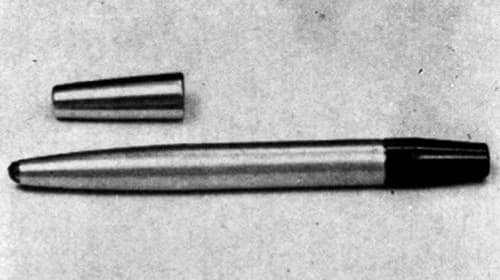

Roll-ons

Above: 1947 Charmel Magic Wand.

Other mechanisms for applying lipsticks were also tried. Included in these were ball-point lipsticks that operated in a similar fashion to ball-point pens. The first two that I know of appeared just after the Second World War – the Magic Wand and the Rol-Lon. Richard Hudnut also tried this form factor when it released Lip Quick in 1959. All failed to gain repeat buyers and were withdrawn from sale.

Size and shapes

Like their containers, the size and shape of lipsticks has also varied over the years. Some of these were due to technical advances but others were simply the result of changes in fashion.

Cross-section: Early lipsticks were round, oval or square in cross-section with the oval and square forms generally disappearing with the demise of push-up cases. With some notable exceptions – like the automatic lipsticks which required a push-up mechanism to work – most lipsticks made from the 1930s onwards have been round or roughly so. Exceptions to this generalisation include the heart-shaped lipsticks introduced by Helena Rubinstein in 1960.

Size: Lipsticks were a lot smaller in the past than we normally see today. There were a number of reasons for this, the two most important being the tendency for early lipsticks to break if they were too long, and the need to keep costs down. Larger lipsticks arrived in the American market with the introduction of ‘Jumbo’ and ‘Super Jumbo’ sizes. These thicker sticks appear to have been introduced to improve margins during the Great Depression.

There is much talk and quite a bit of action on new “Super Jumbo” lipsticks which will make their debut during the coming season. As the name indicates, these will be bigger sticks and bigger cases than the “Jumbo”, the stick that has been on the market for some time and which commonly retails for about one dollar. The new sticks will retail for about $1.50 and are really quite large, some of the cases running to fully one inch in diameter.

There are mixed motives behind this “Super Jumbo” development. Vanity cases, of course, have been getting bigger and more complicated for some time. There has also been very little profit in lipsticks for some time. … [T]he new larger cases cost more and the new larger sticks cost more—about 15 per cent. and 10 per cent. higher respectively. But at a 50 per cent. increase in retail price, that will allow a better profit percentage, and, of course, increase the unit of sale.(AP&EOR, 1937)

Until the end of the 1940s, over 80 per cent of lipstick sales in the United States were still below US$1.00, with many being sold for as little as 15 cents. After the Second World War the average price of lipsticks in the United States rose, with 80 per cent of lipstick sales in the late 1950s now being in the US$1.00 to US$1.35 range (D&CI, 1957). Along with higher prices, small lipsticks all but disappeared.

Length: Very long lipsticks – sometimes referred to as pencil types – were first introduced after the Second World War, without much success. They were often promoted as lip liners and sold in tandem with a coordinated lipstick of the traditional length. Examples include: Revlon’s Lip-Fashion (1947); Gala’s Lip Liner (1949); Dorothy Gray’s Lipstick Couplet (1949); and Flame-Glo’s Longfellow (1950). Another wave of long lipsticks took place in the 1960s with examples that included: Helena Rubinstein’s Fashion Stick (1962); Max Factor’s Fine Line (1962); Revlon’s Sculptura (1963); and the Cutex Fashion Wand Slim-Line (1963).

Tip shapes: These have also been subject to the vagaries of fashion, with particular shapes often promoted as helping the lipstick to produce a defined line on the mouth. Given that any sharply defined line on a fresh lipstick disappears quickly with use, this seems rather spurious to me. The three shapes common to early lipsticks – chisel, bullnose and bullet – were added to over the years and now include exotic forms going by names such as sculptured, blunt, gothic, fishtail, teardrop, moondrop, contoured, bullet-wedge, moondrop-wedge and sculptured-teardrop.

Above: Some lipstick tip shapes in production today. The proliferation of shapes has been made possible through new moulding techniques.

Colours

Even when the use of lipstick became more common in the 1920s they were still regarded by many as being associated with actresses or women of ‘easy virtue’. Most lipsticks from this period were therefore formulated to enhance rather than completely replace the natural colour of the lips. Popular shades were the ‘naturals’ that contained little or no pigments and used a stain to give some colour to the lips without making them ‘look painted’. Some exceptions were made for night make-up when artificial light made darker, vivid colours more acceptable.

See also: Indelible Lipsticks

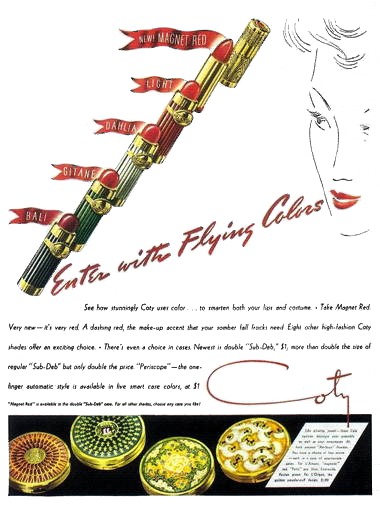

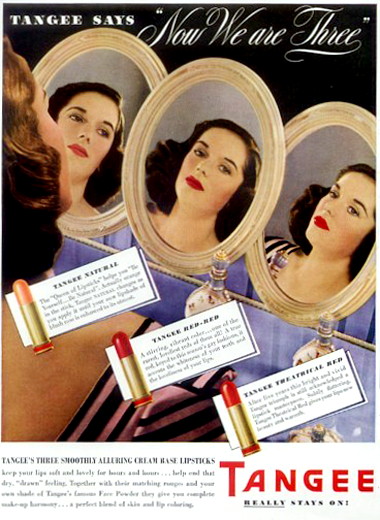

The lipstick that epitomised this situation best was Tangee. Sold by the George W. Luft Company, the lipsticks only came in two shades in the 1920s – Natural and Theatrical Red – with the later shade being for ‘those who insist on vivid color and for theatrical use’. Tangee advertisements strongly criticised the ‘painted look’ all through the 1920s and 1930s and this helped make Tangee the largest selling lipstick in the United States between the wars. It would not be until 1940 that the company would introduced a third shade, Red-Red, to its lipstick range.

See also: Tangee

Tangee was not alone in producing lipsticks with a limited range of colours in this period. Max Factor’s Society Make-up lipsticks only came in three colours (Light, Medium, and Dark) when introduced in 1927, and Dorothy Gray’s lipsticks were still only available in four shades (Light, Medium, Dark, and Evening) in 1929.

The colour [of lipstick] is important. There are two basic shades—Carmine (deep red), and Geranium (bright red). All other colours offered for sale are slight variations of these. The former is used by the brunette type, and the latter by the blonde, it being remembered that artificial light demands a more liberal application.

(Poucher, 1926, p. 52)

This situation changed in the 1930s for two main reasons. The first was the increasing influence of the motion picture industry on fashion. As women in the 1920s began to emulate the make-up they saw on screen, looking ‘artifical’ or ‘painted’ became less stigmatised and obvious colour on the lips became more acceptable. This situation was cemented during the Second World War when lipstick became an almost essential component of a woman’s service uniform. The increased use of colour film in the thirties and forties only served to help move this process along.

A second contributing factor was make-up colour coordination. Until the 1930s, the only requirement for selecting a lipstick – apart from it not appearing too obvious – was that it should match a woman’s rouge.

The lips should have a natural rose hue—but at times the lipstick has to help out Nature. Now the lipstick cannot be considered unless in its relation to rouge. …

Rouge used for the face … should be matched by the shade used on the lips. Hence, let your lipstick match your rouge exactly. Most women need no lipstick—not that this prevents their using one.(Courtenay, 1922, p. 31)

A visitor to France states that the Parisienne today is careful to have her lip-stick, rouge, and powder exactly to tone. If she is a brunette (despite the temporary preference for blondes) she will have a more orange touch to her lip-stick and a darker shade to her powder and rouge. The great secret is that they must have the same tone shade.

(AP&EOR, 1926)

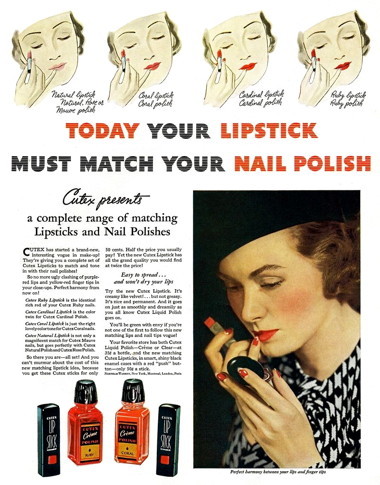

In the late 1920s it became fashionable in Europe to match lipsticks and nail polish so, in 1935, when Northam Warren added lipsticks to its Cutex range, the company naturally harmonised them with their nail polishes.

See also: Cutex

Cutex was not the first nail polish to use this idea. Glazo, for example, bought by Northam Warren in 1928, had introduced their ‘Lipstick Red’ nail polishes into the United States in 1930 as a Parisian fashion trend. Although Glazo did not make lipsticks their advertising described how women could match Glazo nail polishes with their preferred lipstick shade.

Flame, Geranium and Crimson—these are Glazo’s three new lipstick reds. With a light lipstick use Glazo Flame, Geranium with a medium. And with a dark lipstick, use Crimson.

(Glazo advertisement, 1930)

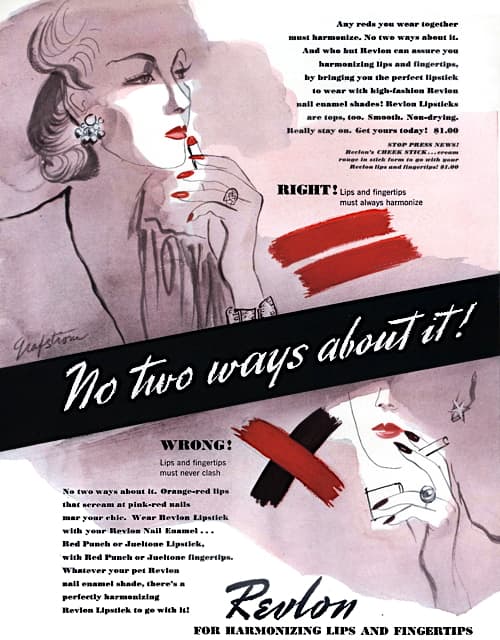

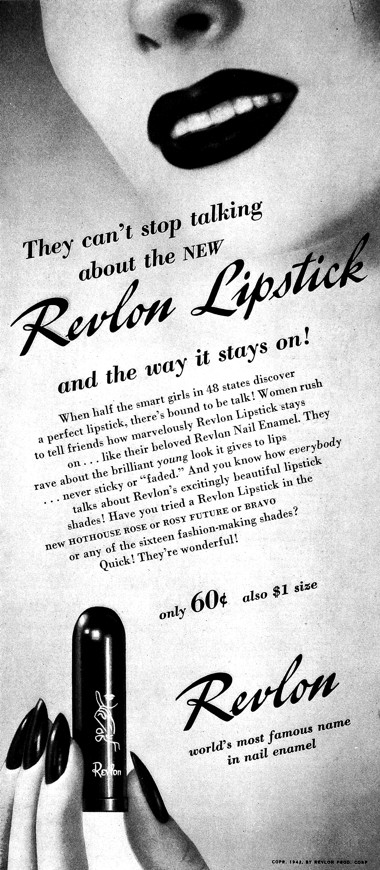

The idea was also adopted by Revlon in 1939 when they began making lipsticks, and formed the basis of their ‘Harmonizing Fingertips and Lips’ and ‘Matching Fingertips and Lips’ campaigns in the 1940s.

Above: 1940 Revlon for harmonizing lips and fingertips.

See also: Revlon

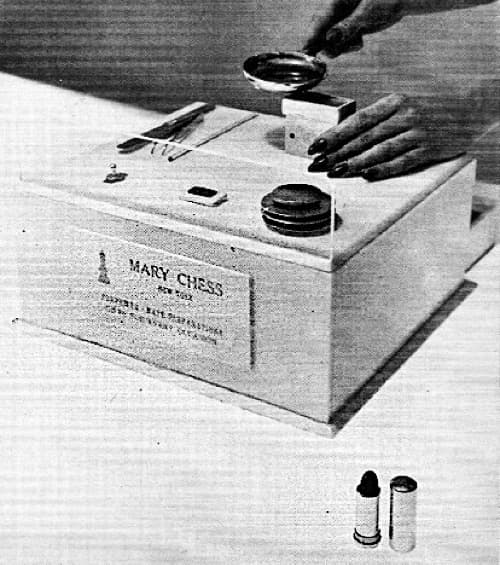

By the end of the 1930s the days of lipsticks in Light, Medium, and Dark were over. From then on lipsticks colours became increasingly subject to fashion and cosmetic companies were soon announcing new matching lipstick and nail polish colours each autumn and spring. In the 1950s, Mary Chess went one step further and introduced a machine which made up ‘lipsticks while you wait’ trying to do for lipsticks what powder bars did for face make-up. Revlon trials the same idea but quickly abandoned it.

Above: 1951 Mary Chess lipsticks while you wait.

See also: Charles of the Ritz Powder Bars

The rise in the intensity of colour, the increased colour ranges found in lipsticks in the 1930s and 1940s, and the move to match lipstick with nail polish, all required a greater reliance on the use of pigments. Even during the ‘lipstick wars’ of the 1950s, which saw a temporary resurgence in the use of dyes, the reliance on pigments continued. In the 1960s and 1970s, when the preference for pastel shades increased, pearlescent lipsticks became more common and, as make-up fashions moved towards a more ‘natural look’, lipsticks became creamier, had better moisturising capabilities and a softer feel. The trade-off was a reduction in durability.

The most common complaint about today’s lipsticks is that “they are thin and smeary and don’t wear well,” compared with those of two or three decades ago. The problem today is to find the proper balance between soft texture and the color durability.

(Anonis, 1974, p. 37)

Fortunately, current formulations have largely overcome many of these earlier problems, enabling lipsticks to have high levels of pigment and enhanced durability without overly affecting adhesion and comfort. Formulations have even reached the point where manufacturers now consider the skin-care aspects of lipsticks more seriously. This takes us right back to the origins of this cosmetic when it was a simple, coloured lip-salve.

Continue onto: Lipsticks (Part 2)

First Posted: 30th October 2013

Last Update: 10th April 2023

Sources

The American perfumer & essential oil review. (1937). New York: Robbins Perfumer Co.

Anonis, D. P. (1974). Perfumes and lipsticks. The Drug and Cosmetic Industry. June, 34-37 & 134-135.

Birge, W. S. (1915). My lady’s handbook. Health, strength, and beauty. New York: Sully and Kleinteich.

Chilson, F. (1934). Modern cosmetics. New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

Courtenay, F. (1922). Physical beauty. How to develop and preserve it. New York: Social Cultural Publications.

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston: D. Van Nostrand Company.

deNavarre, M. G. (1975). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd ed., Vols. IV). Orlando: Continental Press.

Gattefossé, R. M. (1959). Formulary of perfumes and cosmetics. (Trans.). New York: Chemical Publishing Co., Inc.

Hetherington, M. (2015, December 16). Maurice Levy – The man who never invented metal lipstick containers. Retrieved January 6, 2016 from http://collectingvintagecompacts.blogspot.com.au

Keithler, W. R. (1955). Lipsticks. Drug & Cosmetic Industry. 76 (3) March, 55, 330-331 & 425-429.

LIFE (1947). New York: Time, Inc.

Lipsticks. (1927). The Perfumery and Essential Oil Record. October, 421-422.

The manufacturing chemist. (1935). London: Miller Freeman.

New sales approach to cosmetic containers. (1957). Drug & Cosmetic Industry. 81 (1) July, 55, 126.

Piesse, G. W. S. (1857). The art of perfumery, and the method of obtaining the odors of plants, with instructions for the manufacture of perfumes for the handkerchief, scented powders, odorous vinegars, dentifrices, pomatums, cosmetiques, perfumed soap, etc. with an appendix on the colors of flowers, artificial fruit essences, etc. etc. Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston.

Poucher, W. A. (1926). Eve’s beauty secrets. London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd.

Poucher, W. A. (1932). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (4th ed., Vols. 1-2). London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd.

Redgrove, H. S. (1935). A note on lipstick manufacture. The Manufacturing Chemist. April, 123-124.

Sagarin, E. (Ed.). (1957). Cosmetics: Science and technology. New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc.

Sloane. (1933). Teach your clients the correct use of lipstick. The Hairdresser and Beauty Trade. December, 12.

The toilette of health, beauty, and fashion. (1834). Boston: Allen and Ticknor.

Vasic, V. (1958). Perfumes for cosmetics. 3. Lipsticks. Manufacturing Chemist. October, 431-432.

Waggoner, W. C. (Ed.). (1990). Clinical safety and efficacy testing of cosmetics. New York: M. Dekker.

Ward, E. (1937). A book of make-up. London: Samuel French Ltd.

1937 Making up with lipstick.

Two images of Ne m’oubliez pas, one in a leather or cardboard casing, the other in metal. Unfortunately, as this catalogue image also includes Rouge d’Enfer it must have been published no earlier than 1924, well after 1870 when Ne m’oubliez pas was first introduced. What the original packaging looked like I have yet to determine.

1893 Dorin lipstick in a nickel case. The lid fitted over the bottom of the case turing it into a longer stick.

1899 Persian Cream and Lip Salve.

Bourjois stick cosmetics for use ‘pour les lèvres’ (for the lips) as listed in a company catalogue published around 1900: Pommade Rosat, Raisin de Theatre and Rubis Rouge. The containers suggest they were produced primarily for theatrical use.

1899 Vinolia Lypsyl. Sold in fluted, silver-metal tubes. Shades: Rose-Red and White.

1907 Grace Palotta, an Australian actress, with lips painted with greasepaint.

1912 Part of an advertisement from Abraham and Straus, Brooklyn for imported novelties including gold plated lip rouge cases.

Bourjois lipstick in metal case of the push-up type.

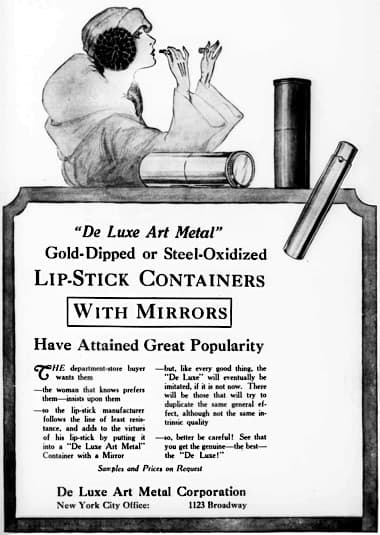

1923 De luxe Art Metal Case. An early attempt at incorporating a mirror into the case.

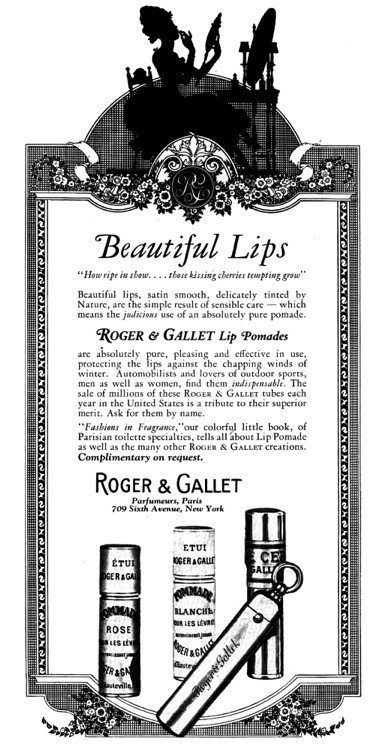

1925 Roger & Gallet Lip Pomades in cardboard and metal cases. The ring enabled the case to be attached to a chain.

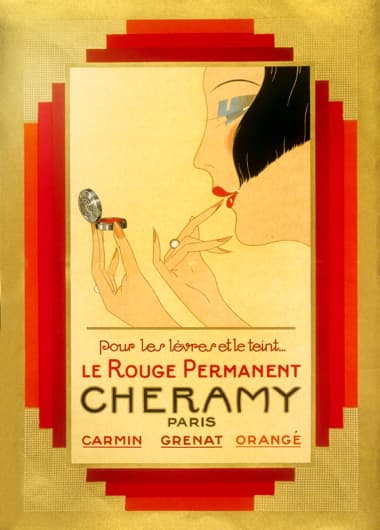

1925 Cheramy Rouge used to apply lip colour.

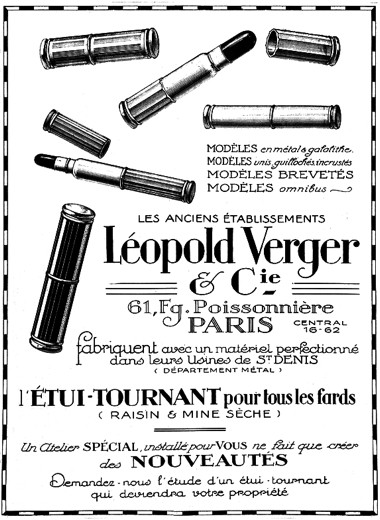

1925 Lipstick cases from Léopold Verger et Cie.

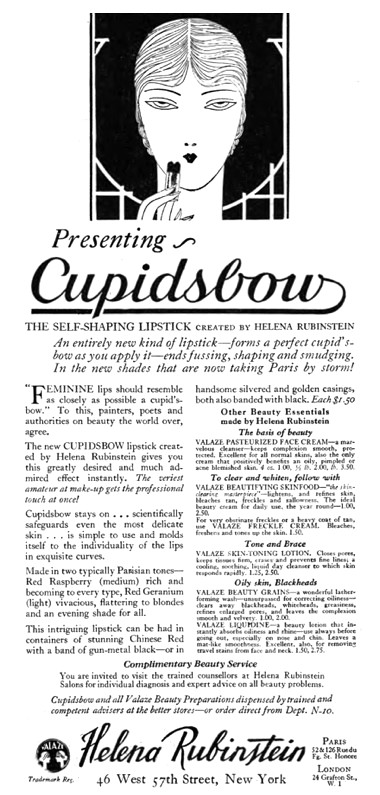

1926 Helena Rubinstein Cupidsbow Lipstick in Red Raspberry (medium) and Red Geranium (light for blondes) shades.

1928 Khasana Superb (Germany).

1929 Decorated lipstick cases from Kissproof.

1930 Jean Patou Lift, an automatic push-up lipstick that can be opened and closed with one hand.

1931 Helena Rubinstein Automatic Lipstick.

1931 Phantom Red.

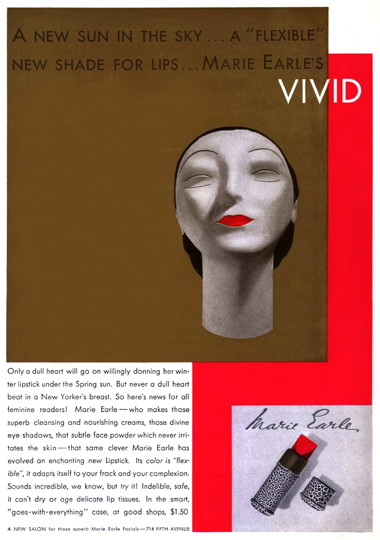

1932 Marie Earle Lipstick with a chisel tip.

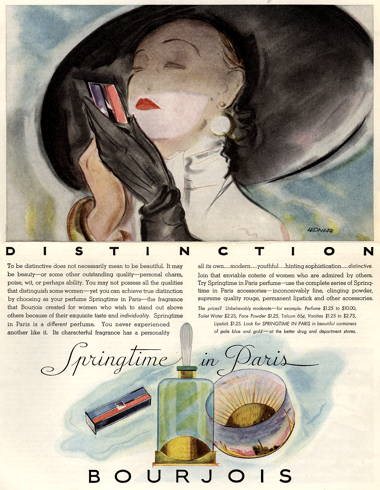

1933 Bourjois lipstick in a square push-up case.

1935 Cutex matches lips with nails with the release of four shades of lipstick to match its nail polish: Natural, Coral, Cardinal and Ruby.

1935 Tattoo Hawaiian Lipstick. A vivid red shade.

1936 Tangee Natural Lipstick that looked orange in the stick but went pink on the lips. Made without pigments it coloured lips with a bromo acid dye.

1937 Angelus Lipstick in shades: Framboise, Light, Pandora, Poppy, Sun Orange, Medium, Coronation Red, and Promenade to match Angelus Rouge.

1937 D’Orsay Automatic Lipstick. Unlike most automatic lipsticks it was round in cross-section.

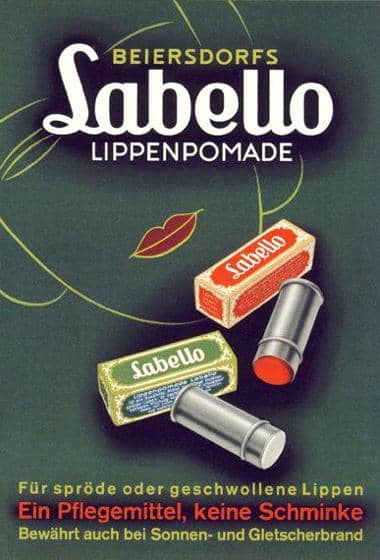

1938 Labello Lippenpomade, a lip balm (tinted and untinted) in aluminium cases.

1938 Ritz lipsticks, some in automatic containers.

1939 Helena Rubinstein Lipstick Plus. The inside case telescoped down so that the lipstick could be substituted with another.

1939 Coty lipsticks in shades: Bali, Gitane, Dahlia, Light, and Magenta Red.

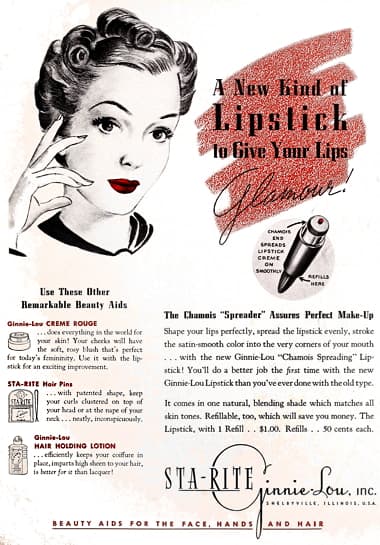

1939 Ginnie-Lou Sta-Rite Lipsticks. One of a number of novel lipstick containers.

1941 Tangee Lipsticks in shades: Natural, Theatrical Red, and Red-Red. Red-Red was added in 1940 and became the third colour in the Tangee lipstick range.

1941 Richard Hudnut Du Barry Emblem Red Lipstick.

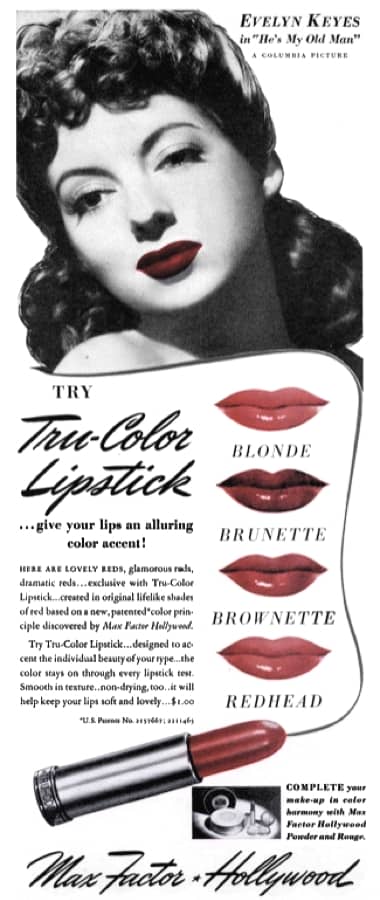

1942 Max Factor Tru-color lipsticks for Blondes, Brunettes, Brownettes, and Redheads.

1942 Revlon Lipstick and Nail Enamel. Revlon began selling lipsticks in 1939.