Nail Powder Polishes

When the well groomed woman of the late nineteenth century removed her gloves, she was expected to display a set of suitably manicured, shaped and polished nails.

Rosy finger-tips and pink nails are things of beauty, and if Nature is stubborn and refuses to lend her aid to their attainment, then art must be called upon. …

After the fingers have been well lathered and washed rub the nails with equal parts of cinnabar and emery, and then with the oil of bitter almonds. The chamois or polisher may then be applied to each nail separately until a fine polish is obtained; but it must be remembered that too high a polish is considered vulgar. To be typical of refinement it should be a soft shining luster.(Butterick Publishing Company, 1892, pp. 321-322)

Powder polishes

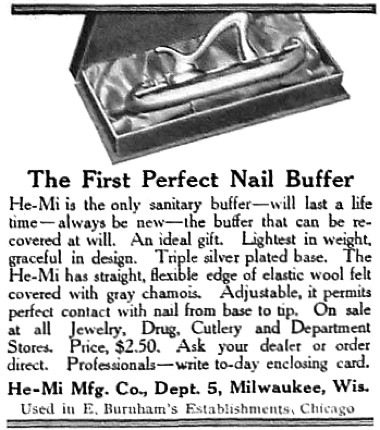

Powder polishes (buffing powders) were commonly used in conjunction with a shaped, chamois leather buffer to mildly abrade (burnish) the nail plate so that a smooth, shiny surface was produced.

Above: Using a nail buffer.

A variety of abrasives – including pumice powder, zinc oxide, precipitated chalk, tin oleate and stannic oxide – were mixed into a base containing suitable lubricants such as paraffin wax and/or beeswax which suspended the powder and added shine. Although it was more expensive, stannic oxide (tin oxide, putty powder, oxide of tin) was generally considered to be the best abrasive as it created the highest gloss. Victorian and Edwardian women were well acquainted with it as it was also used in polishes made for household objects made from tortoise shell or horn.

Above: Early manicure preparations from the Mutual Manufacturing Company, New York, including a powder and a paste along with a nail bleach, orange stick, emery boards and instructions.

Although still around, buffing powders are not commonly used today, being superseded by nail buffing files with their varying grades of coarseness. Current buffing powders are generally sold as pastes (creams) but in the past they were also produced as sticks, blocks, powders and liquids.

Above: Requa’s Rose Nail Polish.

The products were advertised as polishes or enamels but if made in liquid form they could be referred to as liquid nail polishes, liquid nail enamels or both.

The following formulae show the nature of the variations to be introduced to make an effective wax polish in three forms.

Ingredient.

Powder.

Paste.Block or

Pencil.Rosin 160 gm. 160 gm. 160 gm. Yellow wax 60 gm. 60 gm. 60 gm. Soft paraffin 80 gm. 300 gm. 300 gm. White ceresine 500 gm. 200 gm. 500 gm. Kieselguhr 630 gm. 270 gm. 70 gm. Zinc oxide 370 gm. 170 gm. 170 gm. To prepare the powder form, the wax, rosin, and ceresine are melted together, and the soft paraffin added stirring well until the mixture is uniform. It is then allowed to cool and set solid, after which it is broken up, finely powdered, and sifted. For the paste the ingredients are treated in the same manner, when a stiffish paste will result. For the block the same procedure is adopted, but the melted mass is poured into a mould of a suitable shape.

(Silman, 1935, p. 223)

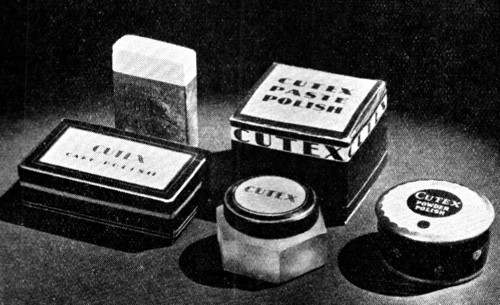

Above: 1935 Cutex Nail Polishes in cake, paste and powder form with associated packaging.

Pigments like carmine or dyes like Bengal Red were often included in these abrasive polishes to make them look more appealing. However, some manufacturers included a larger amounts of dye so that they would stain the nail plate a delicate pink. More adventurous women could dye the nails separately before polishing them.

Polishing may be effected by lightly rubbing the nails across the insides of the hand to which has been applied one or other … [polishing] products or better still by applying the polish on a chamois pad or burnisher.

Some ladies, at this stage, dye the nails a delicate shell-pink or red color. This is a matter of taste, but generally the nails look more attractive with their natural pinkish hue.(Poucher, 1926, p. 71)

Liquid powder polishes were made by suspending the powder in gums and glycerine. The mixture was applied to the nail with a brush before being buffed in the usual way. The suspension had to be as perfect as possible to stop the powder from settling in the bottle. This was usually accomplished by adding additional powders like talc and clay but shaking the bottle before use was also an option.

300 Stannic oxide. 300 Talcum. 100 Osmose kaolin. 2 Tragacanth. 50 Glycerine. 1 Citral. q.s. Water. 1000 Total. (Poucher, 1932, p. 480)

Nail polish liquids are essentially of the same composition [as nail polish powders], plus water and glycerin. The abrasive is kept uniformly suspended in the liquid by a colloidal agent such as china clay. The following is a typical formula:

Stannic Oxide 450 g. Talc 450 g. Glycerin 75 cc. Colloidal China Clay 150 g. Gum Tragacanth or Gum Arabic 3 g. Water 1000 cc. Perfume Sufficient (Bennett, 1935, p. 167)

Powder polishes were not without their problems. As well as requiring a considerable amount of effort to produce an shine that was relatively short-lived, they could also thin the nail plate if over-used or the particulate matter was too abrasive. It is not surprising then that from the 1920s onwards they began to be replaced by liquid forms.

See also: Nail Polishes/Enamels

Updated: 26th November 2019

Sources

Arend, A. G. (1935). Nail polishes and enamels. Perfumery and Essential Oil Record. April, 122-124.

Bennett, H. (Ed.). (1935). The chemical formulary. A condensed collection of valuable, timely, practical formulae for making thousands of products in all fields of industry (Vol. 2). New York: Chemical Publishing Co., Inc.

British pharmacopœia. (1885). London: Spottiswoode & Co.

Butterick Publishing Company. (1892). Beauty its attainment and preservation (2nd ed.). New York: Author.

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston: D. Van Nostrand Company.

Durvelle, J.-P. (1923). The preparation of perfumes and cosmetics. (E. J. Parry, Trans.). New York: D. Van Nostrand Company.

Gattefossé, R. M. (1959). Formulary of perfumes and cosmetics. (Trans.). New York: Chemical Publishing Co., Inc.

Hanckel, A. E. (1937). The beauty culture handbook: A modern textbook of beauty culture and hairdressing for beauty parlour assistants and ladies desirous of practising self-treatment. London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd.

Poucher, W. A. (1926). Eve’s beauty secrets. London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd.

Poucher, W. A. (1932). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (4th ed., Vol 2). London: Chapman & Hall Ltd.

Silman, H. (1935). Nail polishes. The Manufacturing Chemist. July, 223-227.

Above: 1897 Bourjois Emailline. Beauté des Ongles. This product was most likely used to stain the nail a light shell-pink before they were buffed. However, it may have included compounds to give the nail a slight shine. Bourjois also sold Poudre Emailline for polishing the nails.

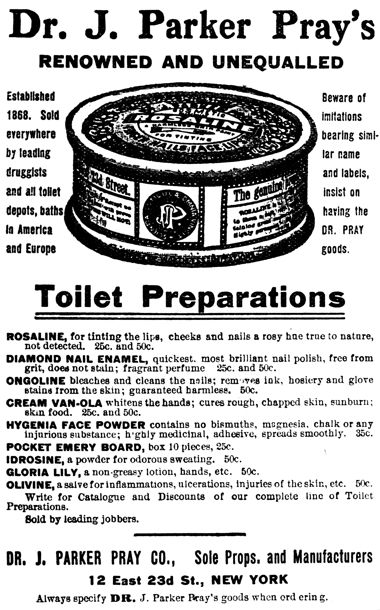

1906 Dr. J Parker Pray’s Diamond Nail Enamel, an abrasive powder polish.

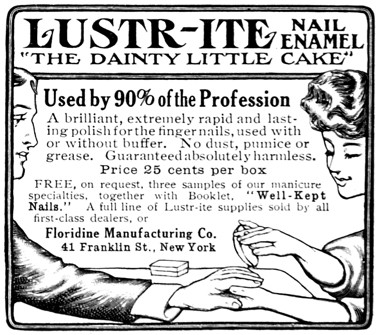

1909 Lustr-ite Nail Enamel, an abrasive polish block.

1909 He-Mi Buffers. Instruments like this were used with powders to give the nail a lasting shine.

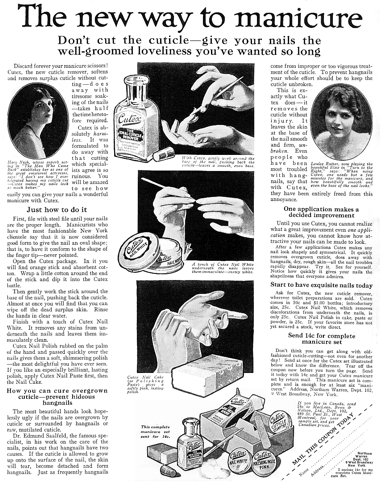

1917 Cutex Manicure Preparations. The company started out selling a cuticle remover but soon introduced a range of nail powder polishes including cake, powder, cream and stick.

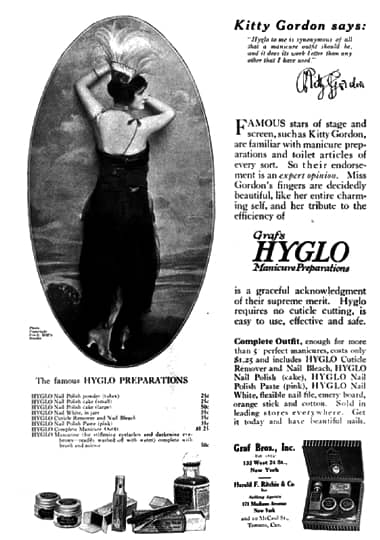

1919 Hyglo manicure preparations including Hyglo Nail Polish Powder, Hyglo Nail Polish Cake, and Hyglo Nail Polish Paste.

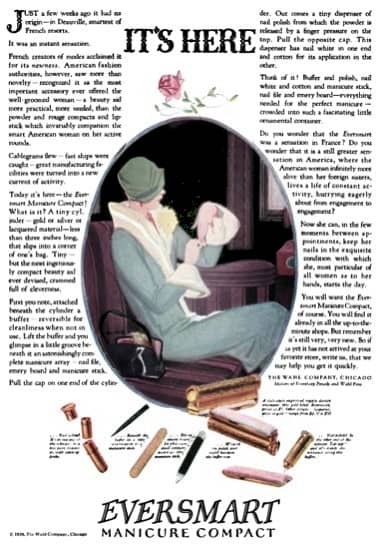

1926 Eversmart. Portable manicure kits like this that could fit into a purse or bag remained popular through the 1920s. The two metal containers are to hold nail white (left) and polishing powder (right).

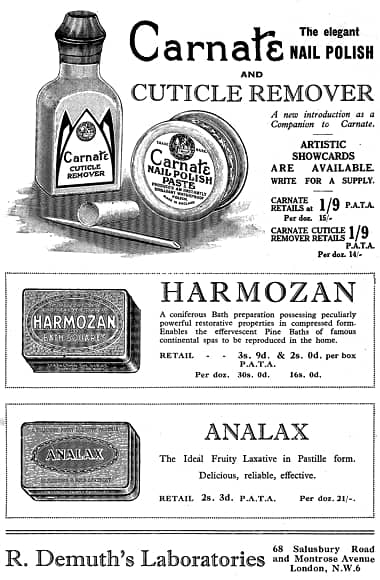

1930 Trade advertisement for Carnate Nail Polish Paste and other products (Britain).