Vitamin Creams

The depression years of the 1930s were difficult times for many American cosmetic companies and they looked for new ways to promote their products and improve sales. As well as engaging in discounting and repackaging to make their lines more economically and visually appealing, many cosmetic companies also added new biological materials to their skin creams during the decade. These substances, which included hormones, glandular extracts, enzymes, and exotic oils from sources such as avocados and turtles, were advertised as skin rejuvenators. The use of vitamins in skin creams stems from this time period.

See also: Turtle Oil, Hormone Creams, Oils and Serums and Placental Creams and Serums

Vitamins

As far back as the eighteenth century, there were suggestions that some diseases were caused by deficiencies in small quantities of essential nutrients. However, it was not until 1912 that Casimir Funk, a Polish chemist working at the Lister Institute in London, developed the concept of vitamins after isolating a substance from rice husks that cured beri-beri. Since the chemical was an amine, Funk called the compound a ‘vital-amine’ which gave us the word vitamin.

The word “vitamine” was coined in 1911, but was published only in 1912, as the Lister Institute of London, where I worked, constantly stricken out the term from my submitted papers for publication. Dealing with B1 at that time I came to the conclusion that it was essential for life and possessed an amine structure. Some of the vitamins do not contain an amine structure and my pupil Drummond dropped the final “e” for that reason. The term was chosen mainly for popularizing this subject among the scientific masses, an aim which was achieved.

(C. Funk, letter, January 18, 1953)

A good deal of scientific research had been done on vitamins by 1930 and a number of diseases had been linked to vitamin deficiencies. However, although the association between vitamins and certain diseases was strong, evidence for benefits from applying vitamins directly to the skin was weak at best. Like hormones, the compounds appeared to have powerful effects in small doses so cosmetic chemists were hopeful that they would prove to have some local effectiveness when applied to the skin. This hope was also founded on the belief that the skin was a good deal more permeable than we would credit today.

The rapid development of the study of vitamins results in constant development of new and novel methods for their administration. One of these is the application of ointments or creams rich in vitamin-containing substances directly to the skin. This, according to its proponents, is a corrective for mild skin morbidities, large pores, lines, wrinkles, sallowness, etc. It is contended that in addition to a general body reaction which all nourishing substances produce in the individual, creams applied locally also produce a prolonged local effect. Numerous experiments have demonstrated that this may be true, and many more will be conducted to elaborate on present knowledge.

(deNavarre, 1933, p. 121)

The two most common vitamins introduced onto skin creams in the 1930s were A and D. Both were oil-soluble and relatively easily to incorporate into a variety of skin creams. More importantly, concentrates of both were available in commercial qualities.

Vitamin D

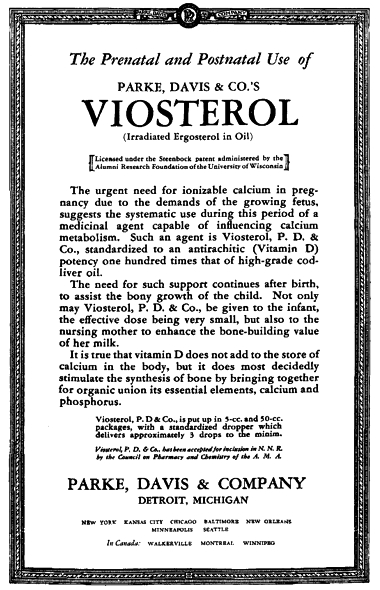

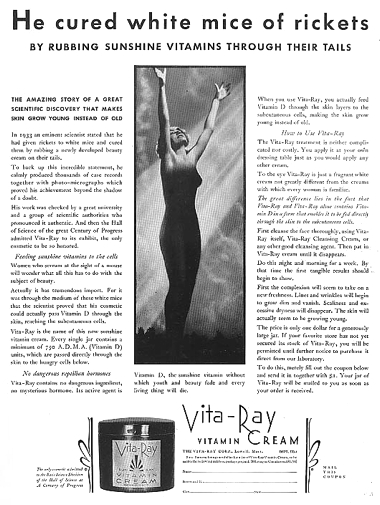

In 1933, the Vita-Ray Corporation began advertising its Vita-Ray Vitamin Cream, each jar containing 750 American Drug Manufacturers’ Association (ADMA) units of vitamin D, promoting it as the ‘sunshine vitamin’. The vitamin D used was probably Viosterol manufactured by Parke-Davis. It was produced by irradiating ergosterol in fat with ultra-violet light, a method developed by Harry Steenbock [1886-1967] in 1923 and subsequently patented.

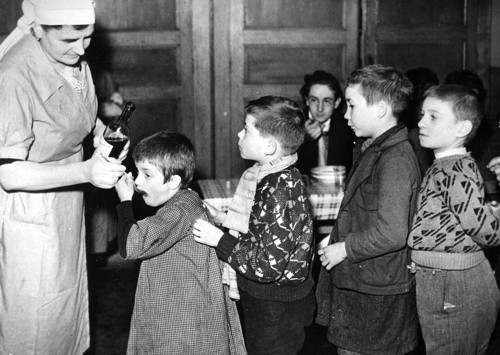

By 1933, Americans were very aware of vitamins, particularly of vitamin D. Rickets was still a problem in many parts of the United States – and in the industrialised world in general and to help prevent the disease from developing, many children were given cod liver oil – a good source of vitamins A and D – and/or were subjected to ultraviolet light treatments – which generated vitamin D in the skin.

Above: 1940 Children being fed cod liver oil.

Above: 1936 Children receiving ultraviolet light treatment.

In the 1930s, the American Medical Association (AMA) encouraged milk producers to fortify milk with vitamin D to protect children from rickets by issuing them with an AMA seal of approval if they did so. Government agencies also encouraged vitamin D fortification by specifying this type of milk in government contracts (Bishai & Nalubola, 2002).

The amount of vitamin D present in the Vita-Ray Skin Cream was very low. It has been estimated that the total amount in a jar of the cream was about the same as that contained in one teaspoon of cod liver oil (Phillips, 1934, p. 117). However, buying it in a skin cream was a good deal more expensive.

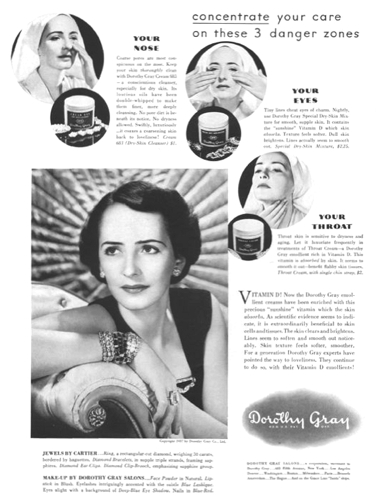

Other cosmetic companies soon followed Vita-Ray. For example, Dorothy Gray added vitamin D to its Dry-Skin Cleanser, Dry-Skin Mixture, and Throat Cream in 1937.

Now the Dorothy Gray emollient creams have been enriched with this precious “sunshine” vitamin which the skin absorbs. As scientific evidence seems to indicate, it is extraordinarily beneficial to skin cells and tissues. The skin clears and brightens. Lines seem to soften and smooth out noticeably. Skin texture feels softer, smoother.

(Dorothy Gray advertisement, 1937)

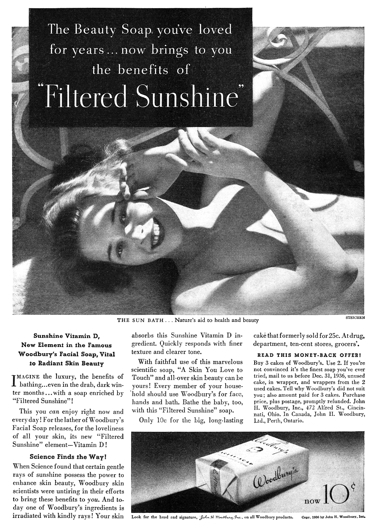

In advertising their vitamin creams Dorothy Gray and Vita-Ray played up the sunshine vitamin angle. To be fair, cosmetic companies were not the only firms to do this and sunshine was used to sell the benefits of vitamin D in everything from beer to soap.

See also: Dorothy Gray

Vitamin A

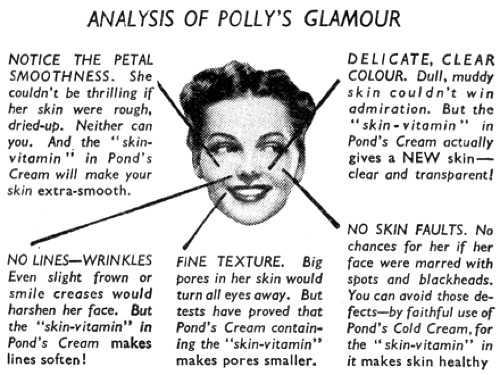

In 1937, Pond’s began adding vitamin A to its skin creams. Unlike the ‘sunshine vitamin’ used by other cosmetic companies, their addition was marketed as a ‘skin-vitamin’.

Pond’s Cold Cream now contains the precious “skin-vitamin.” Not the “sunshine” vitamin. Not the orange-juice vitamin. Not “irradiated.” But the vitamin which especially helps to maintain healthy skin—skin that is soft and smooth, fine as a baby’s.

(Pond’s advertisement, 1937)

After starting with Pond’s Cold Cream, Pond’s added vitamin A to Pond’s Vanishing Cream and Pond’s Liquefying Cleansing Cream. It added a small SV on the labels to indicate that they contained the skin vitamin, and promised that it would fix everything from large pores to wrinkles.

Above: 1939 Part of a Pond’s advertisement for its skin-vitamin creams.

The source of vitamin A that Pond’s used is unknown to me but given that it contained 3,100 units of vitamin A and 165 units of vitamin D (Stabile, 1969), fish liver oil was a strong possibility. Cod liver oil was high in both vitamin A and D but had a strong smell that was difficult to mask. Halibut liver oil was also very rich in vitamin A but only had a slight fishy smell that was easier to cover with perfume (deNavarre, 1933, p. 122). It could also be fortified with vitamin D by adding Viosterol or Vigantol. Caritol, a vitamin A manufactured by the S.M.A. Corporation, was another possibility.

See also: Ponds

Manufacture

Vitamin A and D were both oil-soluble, so it was relatively easy to incorporate them into an oil or cream. Like other biological compounds, degradation was an issue. Vitamin A was affected by light but as most creams were sold in opaque jars this was not a major problem. Destabilisation of the compounds by oxidation was more serious as was masking unpleasant odours if fish liver oil was used.

Lanolin anh. 25 parts Mineral oil 95/100 25 parts Spermaceti 6 parts Beeswax 7 parts Water 36.5 parts. Borax 0.5 parts Vitamin Concentrate qs Antioxidant qs Perfume qs Procedure: (A) Melt together Nos. 1, 2, 3 and 4 and when liquid add 8 and bring the mixture to 70°C. (B) Separately dissolve 6 in 5 and bring to 72°C and add to (A) with constant and continued stirring, until the temperature drops to 45-50°C. Mix 7 with the perfume and add to the cream stirring in thoroughly. Pass through a colloid mill and fill.

Note that the vitamin concentrate is added last with the perfume. This is to prevent loss of vitamin A potency which is adversely affected by heat and air. If hydroquinone is used as a stabilizer for the cream it will also tend to stabilize the vitamin A present. Lecithin might also be used for this purpose.

The final cream should contain not less than 250 vitamin D units per ounce; less than this amount is useless.(deNavarre, 1941, pp. 235-236)

Effectiveness

As mentioned previously, there was very little evidence available to cosmetic chemists in the 1930s about the action and effectiveness of vitamins A or D on the skin. Most studies that showed benefits were conducted on rodents not humans but these studies suggested that the vitamins could be absorbed into the skin and that they had a local action.

Possible benefits included relief from eczema and acne as well as reductions in the appearance of lines, wrinkles and blotchiness. Many cosmetic chemists were optimistic about their potential. Maison deNavarre [1909-1983], who wrote an extensive review on the cosmetic use of both vitamins in ‘The American Perfumer and Essential Oil Review’, concluded that “these [vitamin] creams are of great value as general cosmetics and for numerous other curative purposes, and that future experiments will undoubtedly develop new and additional uses for them” (deNavarre, 1933, p. 123).

Cosmetic companies were happy to include vitamins if there were possible benefits even though definitive proof was lacking, as this rather frank statement from the makers of Dorothy Gray points out:

Dorothy Gray Salons have at all times been on the alert for new developments in the field, and are ready to adopt those materials and processes which after a searching investigation seem to add to the efficacy of Dorothy Gray preparations. Now, in line with scientific research, they announce the addition of Vitamins A and D to all Dorothy Gray emollient creams. Of course, these vitamins are not intended as a substitute for or supplement to vitamins A and D in the diet, and their true value when applied externally as an ingredient of cosmetics has not yet been ascertained.

However, laboratory tests indicate that there is sufficient possibility of their constituting a valuable addition to emollient creams to justify their inclusion. Time will tell the extent of their effectiveness, but in the meantime Dorothy Gray is making available to you whatever benefits may be found to exist.(Dorothy Gray, 1939, p. 5)

The Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act

Following the passing of the The Wheeler-Lea Act and the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act in 1938, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clamped down on arbitrary cosmetic claims including many made for vitamin creams. Many cosmetic companies got a ‘cease and desist order’ about the claims they were making, the one below concerning Pond’s being a good example.

The respondent [Pond’s] is ordered to cease and desist from representing that its creams or lotions have any added beneficial value by reason of their Vitamin A content; that the respondent’s cold cream causes lines, wrinkles or blemishes to disappear and prevents their formation; that the cold cream has any appreciable effect upon the underskin, or leaves it free to function; and that dirt, makeup or other impurities below the surface of the skin may be softened, loosened, or lifted from the underskin through the use of the respondent’s cold cream.

(DCI, 1941, p. 421)

Claims made for vitamin creams in the United States became more sober after 1938 and by the 1940s many cosmetic chemists were also becoming more skeptical that the use of vitamins in skin creams would generate any appreciable benefits.

In view of the known efficacy of their oral application, is there anything to be gained by their external application as a constituent of cosmetics, and, moreover, how can we obtain absolute proof of their absorption by the epidermis? Even supposing that any positive answer can be found to these queries, is not the cosmetician poaching on the preserve of medicine by employing them, providing always that he advertises special claims for his goods attributed to their vitamin content?

(Poucher, 1941, pp. 420-421)

However, as the amount of vitamins contained in skin creams was low some chemists were prepared to accept that they might be doing some good even although the evidence was thin.

There is as yet no detailed published evidence that vitamin A, in clinical practice, possesses any cosmetic effect. On the other hand, it is quite innocuous and, to the author’s mind, scientific experiments have not shown that its inclusion in certain creams may not be of some benefit.

(Harry, 1944, p. 84)

Post war

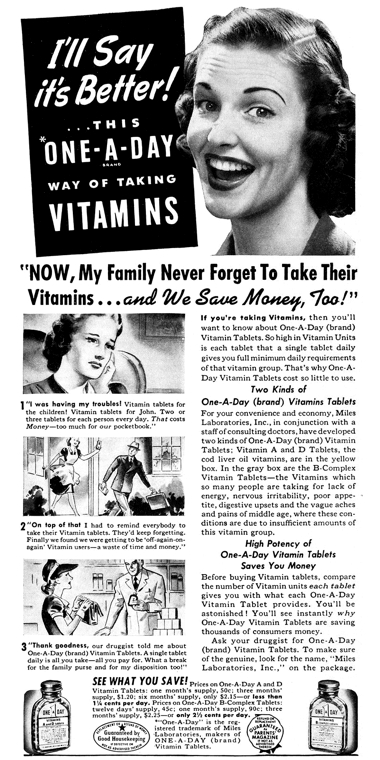

The war years saw a good deal of effort put into educating the general population about good nutrition and by the time hostilities ended it is hard to imagine that anyone in the United States would not be aware of the importance of vitamins. The American pharmaceutical industry saw vitamins as a major revenue source and heavily promoted them as well. Their vitamin advertising embraced the idea that a daily intake of vitamin pills was a ‘necessity’ rather than an option.

Cosmetic companies still promoted the use of vitamins in skin creams after the war but there were fewer stand-alone vitamin creams on the market, Elizabeth Arden’s Ardena Vitamin Cream being one such exception. In general, vitamins were added to masks, dry skin creams, night creams or were used in a supporting role by adding ‘additional benefits’ to whatever was being promoted at the time, whether it be lanolin, royal jelly, hormones, a moisture balm or something else.

This situation changed when Denham Harman [1916-2014] published his questionable free radical theory of ageing in the ‘Journal of Gerontology’ in 1956. This led cosmetic companies to renew their interest in promoting vitamins A, C, and E but this time they concentrated on their role as antioxidants.

First Posted: 1st July 2014

Last Update: 27th March 2023

Sources

Bishai, D., & Nalubola, R. (2002). The history of food fortification in the United States: Its relevance for current fortification efforts in developing countries. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 51(1), 37-53.

deNavarre, M. G. (1933). Vitamins A and D in cosmetics. The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review. May, 121-132.

Dorothy Gray. (1939). Your lovely skin. New York: Author.

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston: D. Van Nostrand Company.

Harry, R. G. (1944). Modern cosmeticology. (2nd ed.). London: Leonard Hill.

Jellinek, J. S. (1970). Formulation and function of cosmetics (G. L. Fenton, Trans.). New York: Wiley-Interscience.

McDowell, l. R. (2013). Vitamin history, the early years. Epub: University of Florida.

Phillips, M. C. (1934). Skin deep. The truth about beauty aids. New York: Garden City Publishing.

Poucher, W. A. (1941). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (5th ed., Vol. 1.) New York: D. Van Nostrand Company.

Stabile, T. (1969). Cosmetics: Trick or treat? (3rd ed.). New York: Arco Publishing Company, Inc.

Wells, F. V. (1953). Hormone and vitamin creams. The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review. February, 117-121.

Kazimierz (Casimir) Funk [1884-1967] aged 58. He first published the term ‘vital amine’ or ‘vitamine’ in 1912. In 1920, Jack Cecil Drummond [1891-1952] suggested that the final ‘e’ should be dropped as not all vitamins were amines.

1929 Viosterol made by Parke-Davis & Co. using a patent taken out by Harry Steenbock. Viosterol was not the only commercial source of manufactured vitamin D. The National Oil Products Company manufactured a vitamin D concentrate it named Vitex and in Germany, Merck and Bayer produced Vigantol by irradiating yeast with ultraviolet light.

1927 Lina Cavalieri Rouge Vitaminé. There may have been no vitamins in this lipstick as none were mentioned.

1934 Vita-Ray Vitamin Cream.

1936 Woodbury’s Facial Soap with vitamin D.

1937 Pond’s with the ‘Skin Vitamin’. Pond’s added vitamin A to their Liquefying Cream, Cold Cream, Vanishing Cream and Danya Lotion.

1937 Dorothy Gray skin creams and cleansers with vitamin D. They added vitamin A in 1938.

1943 Once-A-Day multi-vitamin tablets.

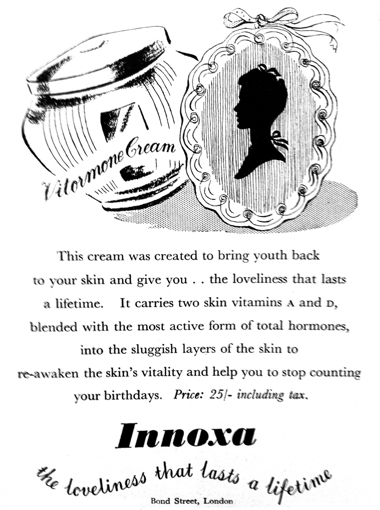

1946 Innoxa Vitormone Cream containing hormones as well as vitamins A & D.

1953 Helena Rubinstein’s Lanolin-Vitamin Formula with vitamin A.

1955 Frances Denney Super Masque with vitamin A.

1955 Retzocrème with vitamins A and D.

1957 Yardley Vitamin Night Cream.

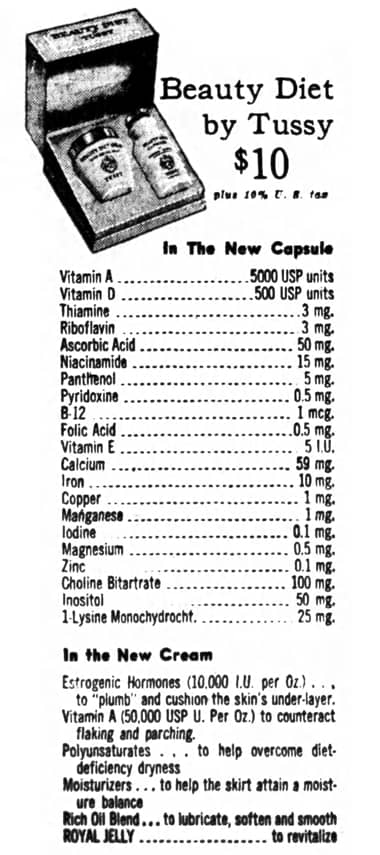

1958 Tussy Beauty Diet. Not all beauty vitamins needed to be in a cream. Tussy introduced vitamin and mineral capsules as part of their Beauty Diet treatment.