Placental Creams and Serums

In 1958, Lambert-Hudnut introduced Elixir Natale and Cream Natale into the American market through their Du Barry line. As announced in the trade journal ‘American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review’ both cosmetics contained Placentine, a placental extract.

Utilizing placenta extract, a combination of the proteins, hormones, vitamins, enzymes and esters that help promote skin cell growth before birth, as a basic ingredient the Lambert-Hudnut division of the Warner Lambert Pharmaceutical Co. will launch on the market next month two new cosmetics. So far as is known this is the first time cosmetics formulated with placentine—a highly concentrated placental extract—has been employed in formulating cosmetics in this country.

(AP&EOR, 1958)

Shipments of the cosmetics were almost immediately seized under the 1938 Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act (FD&CA) as having labels with “false and misleading representations” including statements that the cosmetics contained a ‘Vital Substance’ which could “provide rebirth of the skin, thus enabling the skin to remain in the ‘bloom’ of babyhood; … would provide one with a younger appearance and with a look that was ‘incredibly younger’; … would provide both a softening effect and a tightening effect on the skin; … would overcome the effects of age on the skin, ‘age signs around the eyes and mouth’ and wrinkles; and … would impart a youthful elasticity to the skin which would banish the drying, faded look of age.”

The firm of Richard Hudnut should have known better; after all, they had been through similar problems with the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) a few years earlier when they released Du Barry cosmetics containing royal jelly.

See also: Royal Jelly

This does however, point to one reason why biological compounds, like embryo extract, placental extracts, hormones and royal jelly, were more widespread in European cosmetics than those sold in the United States. The 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act made it difficult for cosmetic manufacturers in America to make the sort of broad claims for their products that were generally accepted in Europe. To do so risked their cosmetics being seized and the company being involved in a lengthy legal action. Richard Hudnut capitulated fairly quickly and rebranded their product as Crème Paradox. It still contained Placentine but most of the earlier claims for its effects on the skin had disappeared.

European rejuvenation treatments

In addition to having weaker laws covering cosmetics, Europe also had a stronger tradition in the use of organ extracts (including the placenta) in rejuvenation treatments, coupled, in the case of skin treatments, with a belief in their ability to penetrate the epidermis. It is not surprising then that most of the industry articles encouraging the inclusion of placental extracts into cosmetics in the 1950s and 1960s came from European (particularly French) sources. Unfortunately, much of the experimental evidence cited in these articles was seriously flawed; some being mere conjecture.

This did not stop European cosmetic companies from including placental in their cosmetics, and companies with strong European ties, like Helena Rubinstein and Richard Hudnut, introduced them into the American market as well. Nor did it stop the Europeans from investigating other tissue sources, including extracts from bovine embryos and amniotic fluid. None of these products proved to be a magic elixir for skin rejuvenation.

Placental extracts

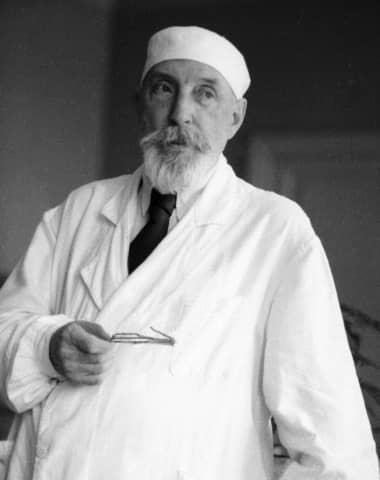

The use of placental extracts began in 1933 with research conducted by Vladimir Petrovich Filatov – best known for his pioneering work in corneal and tube flap grafting – at the Filatov Institute in Odessa, Ukraine.

Above: The Filatov Institute of Eye Diseases and Tissue Therapy.

Filatov believed that many untreatable eye conditions could be improved through injections of biological tissues that had been stored under unfavourable conditions, which, he asserted, stimulated the production of ‘biogenic stimulators’. Although some commentators have suggested that biogenic stimulators might be related to enzymes, exactly what Filatov thought these agents were is unknown; except that they were not hormones or vitamins. What is known is that Filatov used a number of different tissues in his experiments to stimulate the production of these biogenic materials, including placentas.

When Filatov’s work was taken up by German and French interests it contributed to the development of ‘tissue and serum therapies’ in cosmetics. The placenta functions as an intermediary between the mother and the developing foetus and its numerous active substances made it an ideal candidate for rejuvenation research. Placental extracts soon found their way into skin rejuvenation creams, following a path well trodden by other biological compounds like hormones, vitamins, embryo extracts and royal jelly.

See also: Vitamin Creams, Embryo Extracts and Hormone Creams, Oils and Serums

European researchers did not discount the possibility that Filatov’s mysterious ‘biogenic stimulators’ were present in placental tissue but, by the 1950s, they were more likely to stress the presence of placental hormones, vitamins and other more identifiable materials.

The literature which treats of the active substances contained in the placenta is likewise very abundant. The presence in the placenta of a mixture of the most important sex hormones now known, of hormones of the anterior lobe of the hypophysis, of vitamins, of ferments, etc. has been definitely proved, but in many cases the combined effects of these cannot explain the therapeutic successes. Filatov too believes that “biogenic stimulins” which have nothing in common with the hormones or with analogous substances, which appear only eventually after a beginning of decomposition, provoke a specific event.

(Gohlke, 1954, p. 97)

Extraction

In order to be used in cosmetics, the material first had to be extracted. Given that the placenta is a complex tissue, extracts in the 1950s and 1960s were mostly prepared using cold extraction from human or animal placentas. Amniotic fluid was simply drained from the amniotic sac surrounding the developing embryo.

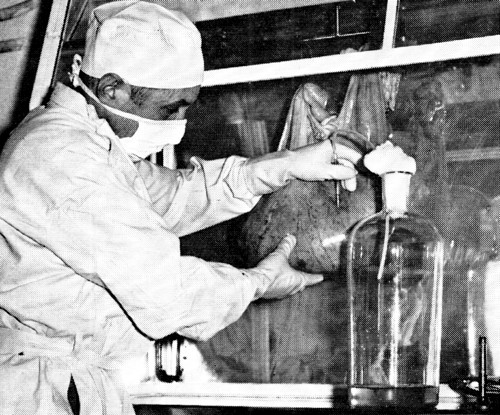

Above: 1967 Extracting bovine amniotic fluid.

The extractions were then preserved using a range of preservative agents so that they could be used in creams, lotions and serums (Sterba & Zenisek, 1961). Needless to say, the amount of extract that actually made its way into any given cosmetic was very, very low.

Uses

A wide variety of cosmetics containing placental or amniotic material found their way onto the market. These included bust creams, eye creams, face creams, masques, cellulite treatments, hand creams, toilet waters, lipsticks, soaps, hair products and even weight-loss cures (Bureau, 1960). In some cases, human placental tissue was used but bovine extracts were also popular.

Above: 1965 Laboratories Akileine Placentonic Cream and Lotion.

The curative properties of placental creams were widely hyped and there were even claims that they were effective in treating skin disorders such as acne and psoriasis.

The surprising successes recorded for the treatment of common acne and acne rosacea are surely not due solely to the better blood supply involving a reinforcement of the defense against infection. The normalization of the acids of the surface of the skin, the regulation of the secretion of the sebaceous glands, and the economy of the vitamins, ferments, and hormones of the skin are important factors that may be influenced by the Placenta solution.

(Gohlke, 1954, p. 99)

Some applications

When used on the face as a cream or mask, the skin was cleansed – to remove any barriers to penetration – before the extract was applied. These days we would increase the likelihood of penetration by exfoliating the skin before treatment.

Senescence: Dried up, flabby, pigmented etc., skins.

In the case of an accentuated senescence, one can use applications of human placenta extracts, reconstituted, on all the face using an impregnated gauze and leaving it for 10 to 15 minutes on the skin after having cleansed the face thoroughly. After removing the gauze, follow with light massage.(Bureau, 1960, p. 38)

When used in the salon, placental treatments were sometimes combined with ultraviolet light therapy or iontophoresis – an electrical treatment which can increase the penetration of material across the epidermis.

See also: Iontophoresis

When used at home, the creams followed well-established practices but, of course, more was usually better.

Daily care of the face: The daily care of the skin must vary according to the state of the skin.

In the case of young skin, a light massage at night, before going to bed with a cream rich in placental extract, or with reconstituted extract, will be sufficient.

In the case of damaged skin (through atmospheric condition—sun, wind, cold) or in the case of over tired skin: 2 applications daily, one in the morning and one at night, are necessary.

For more effective results, it is necessary to use a cream in the morning and at night and to apply the extract under it in the form of a film, every evening preferably or at least three times a week.(Bureau, 1960, p. 38)

Current practice

Unlike the use of hormones – where a good deal of investigative work was carried out by the cosmetics industry over decades – the evidence to justify the use of placental or amniotic extracts in cosmetics remained consistently weak, as it did for royal jelly. In general, the advertising tended to rely on the natural feeling that if it was good for the foetus it must be good for you.

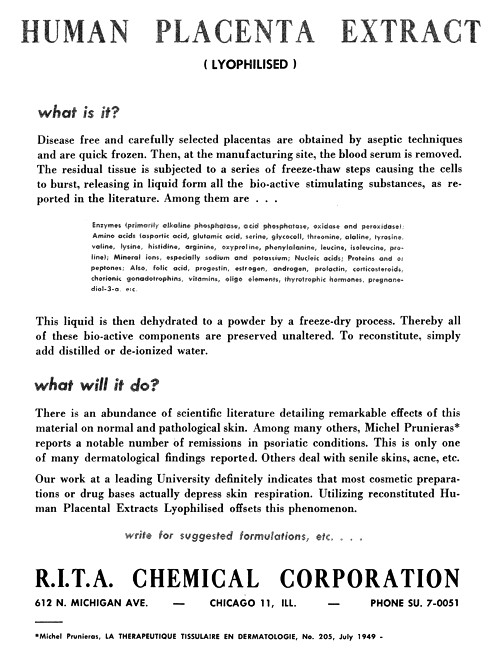

Above: 1960 The RITA Chemical corporation advertising freeze-dried, human placental extract for use in skin creams.

The inclusion of placental extracts in cosmetics peaked in the late 1950s and early 1960s and then declined, with most of the cosmetic industry moving on to other ‘discoveries’. However, even bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) – mad cow disease – did not scare people off completely and it is still possible to purchase a wide selection of cosmetics with placental extracts in their ingredients list.

First Posted: 12th November 2012

Last Update: 23rd November 2020

Sources

Bureau, A-M. (1960). Biological tests demonstrating the activity and cosmetic applications of the total human placenta. The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review. April, 37-39.

Cotte, J. M. (1959). A contribution to the study of some organ extracts. The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review. May, 60-63.

Coote, J., Guillot, B., & Gattefosse, H. M. (1967). Tissue proteins for cosmetic use. The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review. April, 47-52, 55-58.

Gohlke, H. (1954). Use of placental extracts in cosmetics. The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review. February, 37-39.

Myddleton, W. W. (1960). Modern trends in cosmetic formulation. The Journal of the Society of Cosmetic Chemists. 11(4). 192-203.

Sterba, R., & Zenisek, A. (1961). Placenta in the light of current endocrinology. The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review. July, 19-21.

Vladimir Petrovich Filatov [1875-1956].

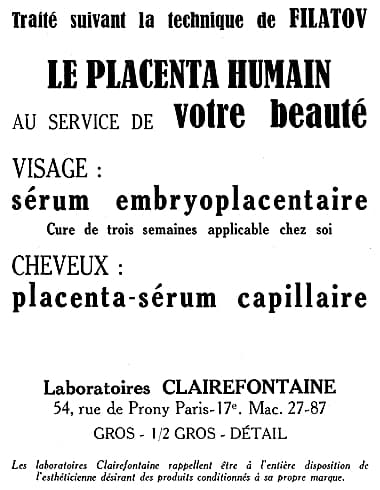

1952 Placental extract from Laboratoires Clairefontaine.

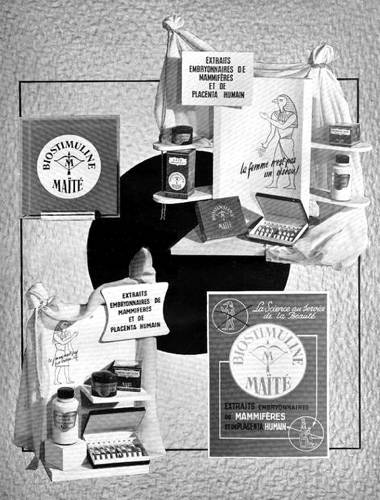

1952 Maité Biostimuline containing embryo extract and human placental extract.

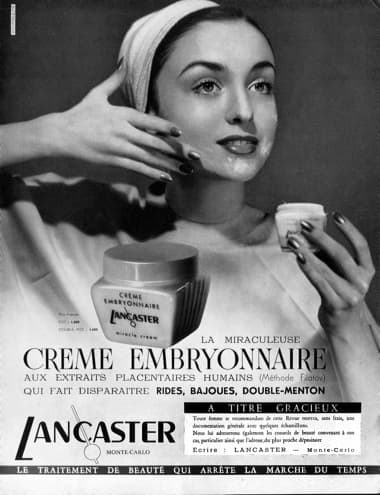

1955 Lancaster Crème Embryonnaire made with human placental extract.

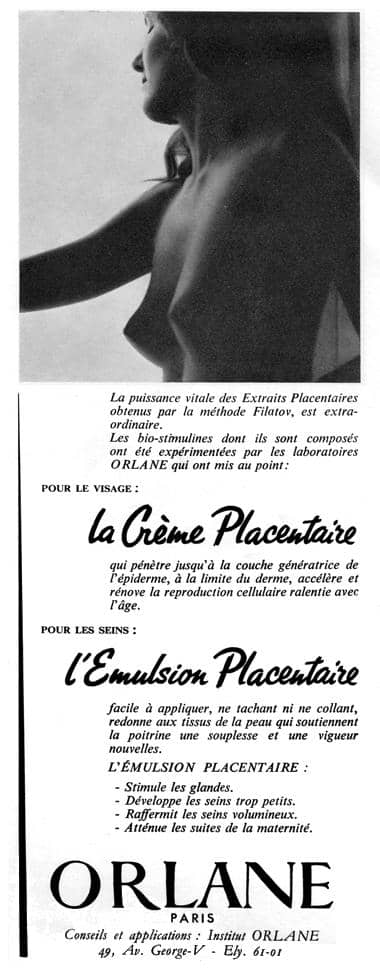

1956 Orlane Crème Placentaire and Emulsion Placentaire.

1958 Ello-Placenta Cream.

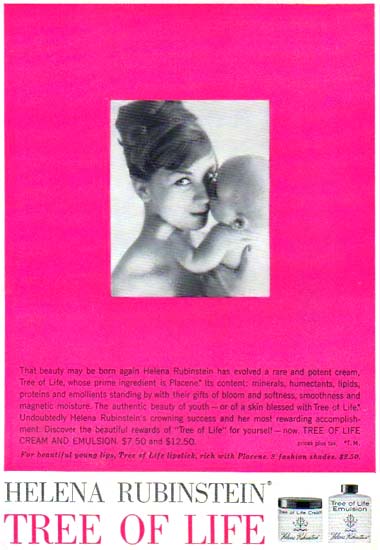

1958 Helena Rubinstein Tree of Life containing ‘Placene’ which Rubinstein also used in lipsticks. She claimed to be using human placentas to make these cosmetics.

1958 Placentubex developed by Merz & Company, of Germany in 1953. In the United States it was marketed by Maradel Products as Redeema.

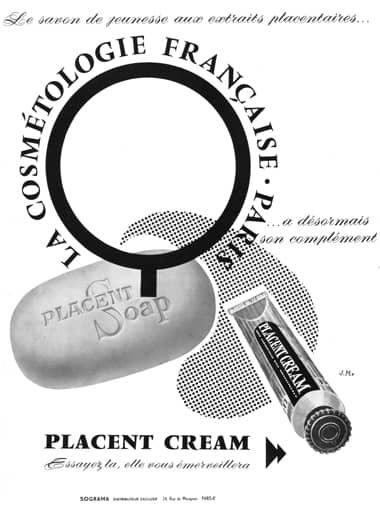

1958 La Cosmétologie Française Placent Cream and Placent Soap.

1960 Richard Hudnut’s Du Barry Crème Paradox containing Placentine.

1961 Trade advertisement for Louis Philippe make-up with amniotic fluid.

1963 Part of an advertisement for Lancaster Cosmetics titled ‘The most efficacious Beauty Treatments from Paris’. As well as Crème Embryonnaire other placental products produced by Lancaster weren Tissue Serum ‘S’ for breast firmness and Tissue Serum ‘V’ for facial wrinkles.

1963 Hormocenta Placento-Creme.

1963 Mardadel Products (later Dell Laboratories) Redeema (Placentubex).