Cerates

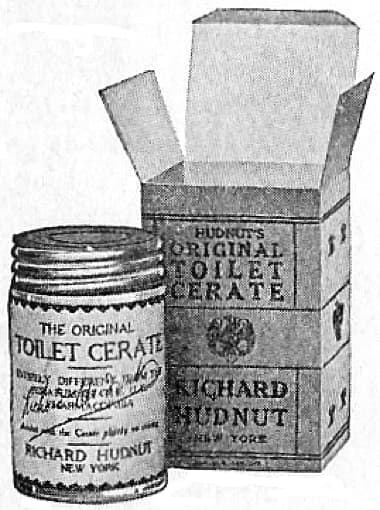

Amongst the beauty products sold by Richard Hudnut from his nineteeth-century New York pharmacy was a skin-care cosmetic he labelled a ‘Toilet Cerate’. It came in two forms – Original Toilet Cerate and Violet Toilet Cerate – with the violet fragranced form being more expensive. “It is a skin food especially suited to give strength to the skin, and as a tissue builder it excels” (Richard Hudnut, 1919, p, 2).

Also see: Richard Hudnut

Pharmaceutical cerates

Like many other early skin-care cosmetics, cerates were first developed for pharmaceutical use and it is there that we must look for their origins.

Nineteenth century pharmacists regarded cerates as a type of ointment. Like ointments, cerates had a base compounded from fats, petrolatum and/or oil but they were formulated with more wax (latin: cera), and occasionally resins, so were stiffer and had a higher melting point than ointments. This meant cerates would not easily melt or run when applied to the skin, a useful medicinal characteristic that allowed them to be spread over muslin or other bandage materials.

Ointments are soft or semi-solid fatty masses, intended to be applied to the skin by inunction or “rubbing in”, and of such consistence that they are partially or wholly liquefied by the heat of the body.

Cerates are ointments plus the addition of wax, which gives them a firmer consistence and higher melting point. The name of the class is derived from cera, the Latin for wax.(Beal, 1908, p. 92)

Comparing a typical ointment and cerate base shows the proportion of oils and waxes used in each:

Ointment Base

White Wax 5 parts Wool Fat (unhydrated lanolin) 5 parts White Petrolatum 90 parts Cerate Base

Olive oil 60 parts White Wax 30 parts Spermaceti 10 parts

Pharmaceutical cerates generally functioned as skin protectants or were used to soothe inflammation but, like ointments, they could have other ingredients added to them to extend their capabilities. Some of these formulations – such as Turner’s Cerate made with calamine; or Goulard’s Cerate made with subacetate of lead – became standard recipes used across the pharmaceutical profession.

Ceratum Calaminae Turner’s Cerate

Yellow Wax 3¼ ounces av. Olive Oil 10 fl.ounces Prepared Calamine ¼ ounces av. Melt the wax with the oil, and when cool enough to begin to thicken, add the calamine, and stir until cool. This may also be prepared by mixing 1 part prepared calamine with 5 parts simple cerate.

This has long been popular under the name of Turner’s cerate as a drying, healing dressing for sores, ulcers etc.(Fenner, 1904, p. 337)

The ability of cerates to stay in place and provide a protective barrier meant they were also a good choice for pharmacists when formulating salves to soften the skin or prevent chapping. Cerate gloves could also be made up for a lady to wear overnight to soften her hands. A cerate lip salve could help prevent lips from chapping in cold, dry weather and adding a little red colouring matter, such as alkanet, would turn it into a lip rouge.

Cerate for Chapped Hands

Spermaceti 2 ounces Glycerine ½ ounce Sal ammoniac 1 drachm. (Cristiani, 1877, p. 352)

Ceratum Rosarum. Lip Salve.

Oil of Almonds 8 fl.ounces White Wax 4 ounces av. Alkanet Root ½ ounce av. Digest the alkanet in the almond oil for some days, then filter or strain, add the wax, melt and perfume while cooling with Otto of Roses, or other suitable perfuming oil a sufficient quantity. This makes a nice lip salve.

(Fenner, 1904, p. 340)

Toilet cerates

Richard Hudnut distinguished between two types of cerates: those made with an oil base; and those compounded with glycerine. Hudnut’s Toilet Cerate was sold in a glass jar with a rustproof aluminium lid. This suggests that it contained water so may have been compounded with glycerine. The presence of oils and wax meant it could be used as a skin protectant and massage cream and if lanolin was added it could also be described as a skin food.

This most useful preparation is readily absorbed by the skin, and owing to this and certain other characteristics, it is particularly adapted to use as a massage cream, while as a general healing application to the skin when burned, irritated, chapped, inflamed etc., it has no superior. It is entirely different to the so-called “Cerate” of the Pharmacopoeia, and is greatly superior to it in its own sphere of usefulness.

Toilet Cerate may be used at any time to protect the skin from the effects of wind, glare and dust, when yachting, automobiling, etc. It should be gently rubbed in and the superfluous portion removed with a soft towel.(Hudnut, 1915, pp. 18-19)

Also see: Skin Foods

This type of cerate has some similarities with traditional cold creams which were also made with oils, wax and water, generally rose water. It is no coincidence that in pharmacy circles, cold creams – which were originally compounded by the Roman physician Galen from beeswax and olive oil – were also known as Galen’s Cerate (Ceratum Galeni) or, when made predominantly with spermaceti rather than beeswax, as Spermaceti Cerate (Ceratum Cetacei).

Ceratum Galeni., Cérat de Galien, Fr.

Oil of Sweet Almonds, 8 fl.ounces White Wax, 2 ounces av. Rose Water, 6 fl.ounces Melt the wax in the oil by heat, and while cooling, gradually add the rose water, beating it with a wooden spatula.

This cerate is considerably used in French pharmacy as a cerate or ointment base. It is similar to cold cream, or rose-water ointment, and is used for similar purposes.(Fenner, 1904, p. 338)

Also see: Cold Creams

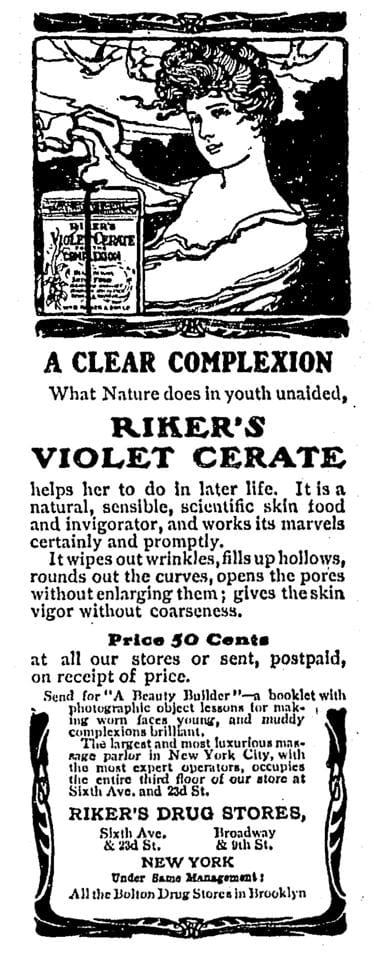

Another well-known create, Ricker’s Violet Cerate, was described as being non-greasy with a tendency to tingle when applied to the skin, both characteristics of glycerine-based cerates.

Greasy creams do not freely enter the skin; they form an oily coating. Riker’s Violet Cerate is not a grease. It dissolves freely in water.

The skin and sub-cutaneous tissues will absorb large quantities of the Cerate. This absorption is so rapid that in some cases is causes a tingling sensation where applied. This sensation should not alarm the user. It is caused by the parched and starved skin devouring the Cerate with such avidity. It is rarely that the tingling is felt, and is then only of about ten minutes duration.(W. B. Ricker & Son Co., 1901, p. 3)

Glycerine (also glycerin) would help a cerate feel less greasy, appear to be rapidly absorbed and would benefit the skin in a manner similar to glycerine starch creams or jellies.

Ceratum Glycerini. Sp., Cerato de Glicerina, Glycerin Cerate

White Wax 12 parts Almond Oil 60 parts Glycerin 30 parts Melt the wax, add the oil and incorporate the glycerin while cooling. (The addition of borax 2 parts, dissolved in the glycerin facilitates the mixing of this cerate and is otherwise advantageous).

(Fenner, 1904, p. 338)

Also see: Glycerine Creams and Jellies

Disappearance

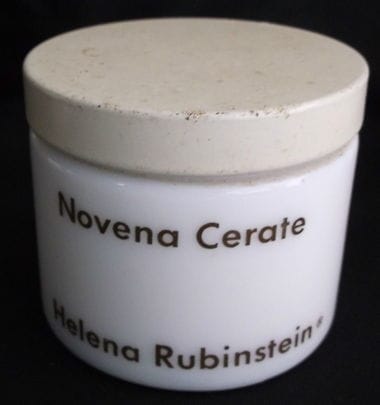

Beauty products specifically sold as cerates were not common and largely disappeared from shelves after the First World War when cold and vanishing creams became dominant. There were exceptions. Ricker continued to produce their Violet Cerate into the 1920s at least, Richard Hudnut still had both Original and Violet Toilet Cerates on its product list in the early 1930s, and Rexall Drug Stores made a Violet Cerate Cream through to the 1950s. Helena Rubinstein also persisted with the Novena Cerate she had introduced earlier in the century but altered its function. Originally sold before the First World War as a cleanser and nursery cream, by the late 1950s, Novena Cerate was being marketed as a ‘rich, bland, soothing, night cream for the face and neck’.

First Posted: 2nd November 2015

Last Update: 27th June 2022

Sources

Beal, J. H. (1908). Prescription practice and general dispensing. An elementary treatise for students of pharmacy. Author.

Bliss, A. R. (1937). Ointments, pastes, cerates. The Drug and Cosmetic Industry, 40(4), 490-492.

Cristiani, R. S. (1877). Perfumery and the kindred arts. Philadelphia: Henry Carey Baird & Co.

Fenner, B. (1904). Fenner’s twentieth century formulary and international dispensary (13th ed.). Westfield, NY: Author.

Richard Hudnut. (1915). Beauty book containing some account of marvelous cold cream and other complexion specialities [Booklet]. New York: Author.

Richard Hudnut. (1919). The secrets of beauty [Booklet]. New York: Author.

W. B. Ricker & Son Co. (1901). A beauty builder [Booklet]. New York: Author.

1919 Richard Hudut Original Toilet Cerate.

Martin & Pleasance Calendula Cerate.

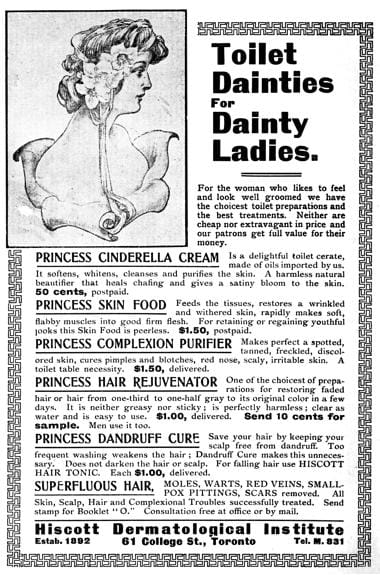

1900 Princess Cinderella Cream described as a ‘delightful toilet cerate’.

1905 Ricker’s Violet Cerate.

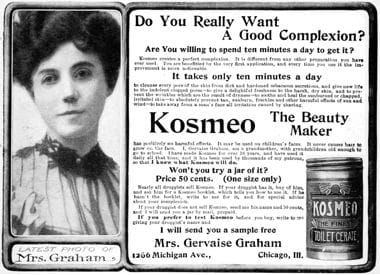

1906 Kosmeo Toilet Cerate.

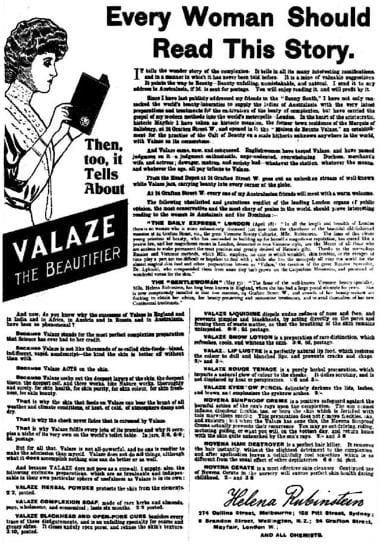

1908 Helena Rubinstein cosmetics including Novena Cerate.

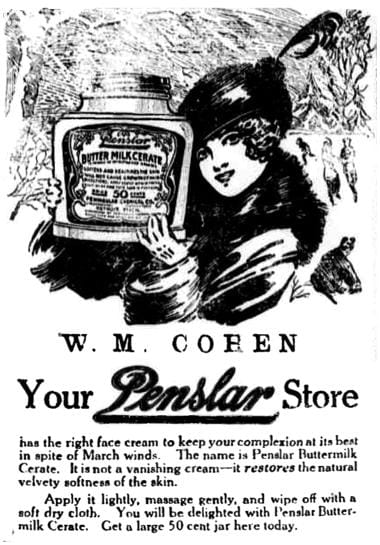

1914 Penslar Butter Milk Cerate.

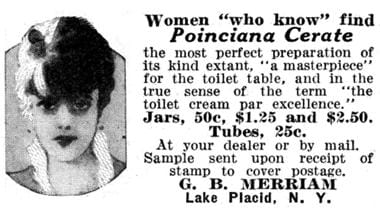

1915 G. B. Merriam Poinciana Cerate.

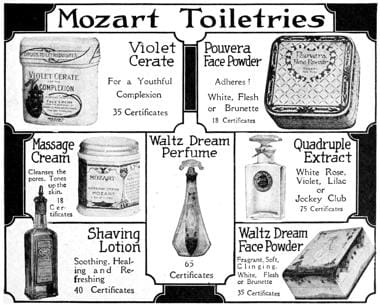

1922 Mozart Toiletries Violet Cerate.

Helena Rubinstein Novena Cerate.