Bleach Creams

Western ideals of beauty required fashionable women of the nineteenth century to have a soft, white skin, free from imperfections. A flawless, white skin could be marred from stains produced by the dyes used to colour clothing and furs, pigmentation irregularities from freckles, moth patches, melasma/chloasma and liver spots, or darkened from exposure to the sun. To treat these problems, or to lighten their skin overall, many women turned to bleaches.

Above: Ro-Zol Complexion Clarifier and Bleach (Smithsonian).

Bleach ingredients

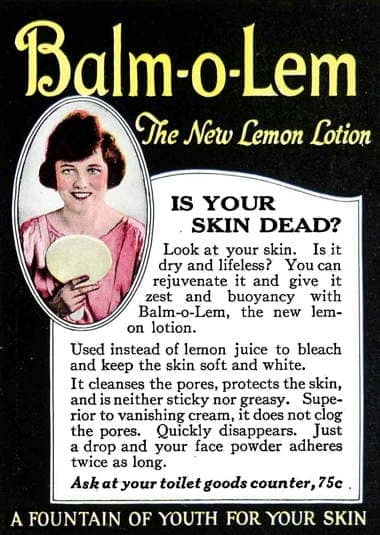

Over the years, a wide variety of compounds have been listed as bleaching the skin. Some – such as muriatic acid, ammonium chloride, lactic acid, hydrogen peroxide, perborates and corrosive sublimate – were dangerous but others – including lemon juice, glycerine, almond meal, elder-flower water, cucumber juice and buttermilk – were less aggressive. These ingredients could be used separately or in combination, with many skin bleach recipes combining dangerous and more innocuous materials.

If you … have let yourself “burn” or tan from the sun or the wind, you can console yourself, for sunburn disappears of itself when you have stopped the cause which has produced it. If you want to hasten its departure, you have a choice of ways, of which we will show you some, (1) Cut in pieces a fresh cucumber and leave it to soak in milk during five or six hours, and wash yourself in the evening with this milk, and the tan will disappear in two or three lotions. (2) Mix 8 oz. 29 grains of milk of almonds, 31 grains of sulphate of zinc, and 8 grains of sublimate, with a sufficient quantity of alcohol; wash your face three times a day and the skin will soon recover; (3), and lastly, an excellent receipt is to mix an equal quantity of lemon juice, glycerine, and rose water.

(The Countess C—, 1901, p. 66)

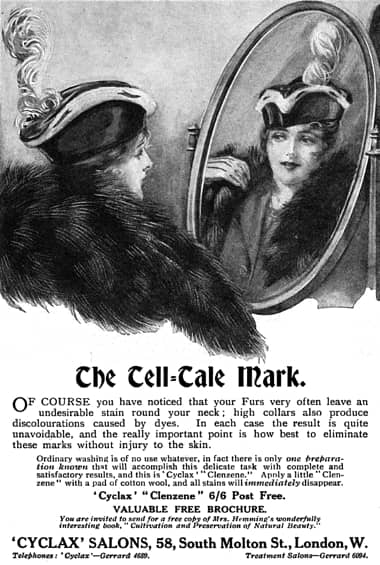

A full scientific understanding of how some skin bleaching compounds functioned was lacking in the nineteenth century but later investigations indicated that they worked by inhibiting the natural formation of skin pigments; by oxidising skin pigments in the skin; and/or by removing surface skin cells containing pigment through exfoliation. Only those compounds that oxidise skin pigments can truely be said to bleach. So, although a pumice stone might be used as part a bleach treatment for a neck discoloured by furs, scarves or high collars, it is lightening the skin through exfoliation rather than bleaching it.

The neck often becomes discoloured by furs; cheap ones are especially harmful in this respect. The neck bleach must be of a mild nature, and should follow the lines of the general skin bleaching already suggested in these pages. It is advisable in many cases where the skin is discoloured from the use of furs to use a little pumice stone. This requires great care, for undue friction would break the surface of the skin, and probably do more harm than good. This is part of the bleaching treatment, but is not advised for frequent use. The new skin must be kept pliable and healthy. Pumice is only used in very stubborn cases, where the skin has become somewhat hard.

(Sloane, 1934, p.12)

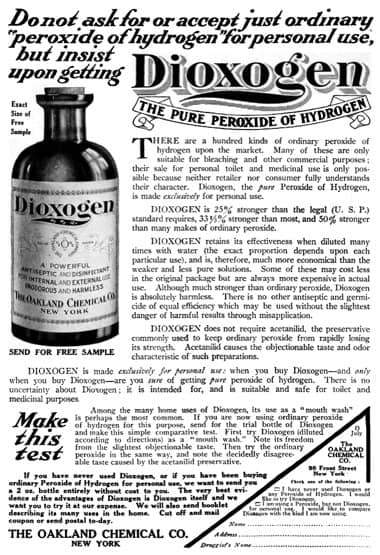

Two compounds commonly used in skin bleaches were hydrogen peroxide and ammoniated mercury.

Hydrogen peroxide:

This compound oxidises skin pigments so is a true bleach. As well as being used on the skin, it was also employed to lighten head hair, remove stains from finger nails and to lighten facial and other body hair rather than remove the hair with a depilatory cream or by waxing.

See also: Hair removers

It was also added to a number of skin creams to produce a peroxide cream.

Per cent Petrolatum 49.0 Spermaceti 12.0 Mineral oil 25.0 Lanolin 3.0 Glycerin 3.0 Hydrogen peroxide (17 Vol.) 3.0 Lactic acid 0.5 Citric acid 0.5 Water 3.0 Perfume 1.0 Procedure: Mix the glycerin with water and dissolve lactic and citric acids. Melt the spermaceti, lanolin and petrolatum and then add the mineral oil, and mix thoroughly; then add the acid solution with rapid stirring. Mix for two hours, add the peroxide and perfume. This product is very strong and the user should be directed to use it with caution.

(Chilson, 1934, pp. 113-114)

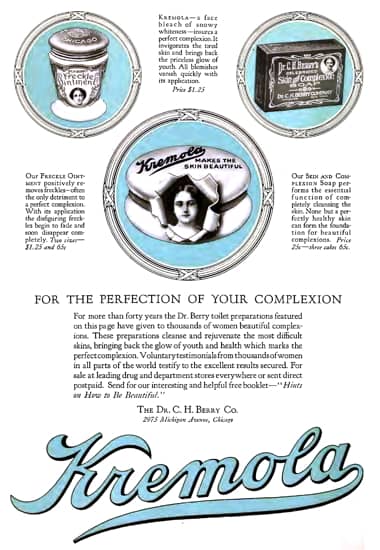

Ammoniated mercury

As well as lightening skin pigments, ammoniated mercury reduces the production of the skin pigment melanin by inhibiting the enzyme tyrosinase, and it also has an exfoliating effect on the epidermis. This meant it works as a depigmenter, a bleach, and an exfoliant. The compound was found in a wide variety of commercial bleach creams even though it was a known poison. It was frequently combined with bismuth subnitrate, although the reasons for this were unclear. Some chemists suggested bismuth subnitrate helped reduce irritation, others that it sped up the bleaching process; still others thought that its only use was as an opacifying agent (Ozier, 1957, p. 216).

Per cent Petrolatum 56.0 White beeswax 20.0 Mineral oil 7.0 Lanolin 3.0 Ammoniated mercury 6.0 Bismuth subnitrate 7.0 Perfume 1.0 Procedure: Grind the ammoniated mercury and bismuth subnitrate with part of the petrolatum through an ointment mill until smooth and impalpable. Melt the beeswax, lanolin in the remainder of the petrolatum and add the milled base. Mix for two hours and add the perfume.

(Chilson, 1934, pp. 113-114)

Also see: Mercolized Wax

Salon bleach treatments

Although a bleach treatment could be done at home, many women preferred to include it as part of a salon beauty treatment, particularly in autumn after summer holidays came to an end. Early beauty salons used a range of compounds in their bleaches, with less aggressive ingredients – such as almond meal, buttermilk and elderflower water – being used on more sensitive skins.

A MILD BLEACH FOR SENSITIVE SKIN

1. Cleanse with cleansing cream

2. Employ Vapor and Steam Generator.

3. Red Light over Bare Skin

4. Pat in Muscle Oil.

5. Apply Tissue Cream.

6. Manipulations.

7. Apply mask of almond meal and corn meal, equal parts mixed with milk, over gauze wet in milk. This gauze should be about eighteen inches square.

8. Dry with Red Light about 20 minutes.

9. Remove mask by lifting the gauze from the face.

10. Sponge face with milk until freed of all the powder.

11. Pat in a little Muscle Oil if the skin appears dry.

12. Make-Up. Medicated Powder.(Blood, 1927, p. 145)

However, should a more intense action be required then hydrogen peroxide was generally used; a substance therapists were very familiar with as it was a common hair lightener. Although a known irritant, the concentration of hydrogen peroxide was easily adjusted, enabling allowances to be made for individual clients. It could be mixed into a paste to make a face mask, laid on the face in cotton swabs, or dabbed on with cotton wool to lighten hyper-pigmented spots such as freckles.

As in all facial treatments, the client should be in a recumbent position to allow for ease in manipulation. Have in readiness a receptacle containing peroxide of hydrogen with a few drops of ammonia added. About 3 drops of the latter is quite sufficient for 1 fluid ounce of peroxide. More would be far too drastic and would burn when in contact with the skin. Cleanse the face thoroughly with a piece of cotton-wool dipped in peroxide, carefully avoiding both lashes and brows. A little cream should then be massaged into the skin and the surplus removed. The peroxide should now be swabbed on to the face where the patches of tan are to be removed, and also on any other part where the skin appears unhealthy or without tone. Great care must be observed to see that the bleaching solution does nor come in contact with the eyelashes or brows, otherwise the colour will be taken entirely away.

If the client does not complain unduly of the tingling sensation usually experience, packs of cotton-wool, first saturated in the bleach, may be laid on the skin. Do not place swabs on the eyes during this treatment; there is always the danger of absorption from the peroxide on to the wool. Allow the pack to remain on for 5 to 10 minutes, according to the texture of the skin, and then remove. Gently cleanse the face with witch-hazel, and once again massage with a good cold cream containing peroxide. Wipe off. Apply astringent and make-up.

If the skin is deeply burnt, it may take one or two bleaches to clear the condition.(Hanckel, 1937, pp. 113-114)

Until the Second World War at least, peroxide treatments were sometimes combined with direct current (galvanism) electrical treatments and/or with red light. The usual reason given for this is that they helped force the bleaching agents into the skin.

Above: 1907 Bleaching skin with a negative carbon electrode in a Marinello salon.

Instantaneous bleaching, as it is called, consists in making the skin from four to six shades lighter in one treatment by means of this process. First of all the lettuce creme is applied and allowed to remain for a few moments. It is then removed by means of soft bits of cloth or cotton, and the skin thoroughly washed with a strong solution of soda in order to remove any signs of oil. A paste is then made by adding to the refining powder some dioxide of hydrogen, and this is spread over the face and neck and allowed to dry. If one wishes the arms bleached or wishes to make the shoulders more presentable for an evening party, the process may be continued over all of the surface. As the paste drys [sic] a pricking burning sensation sometimes is felt. This is usually due to the action of the dioxide, and in very sensitive subjects has been known to make the face appear red and blotchy for a day or so though afterward it looks much better. However, it is well to ascertain the condition of the skin before applying the paste and then if it is very sensitive dilute the dioxide with witch hazel before applying it.

After the paste has become thoroughly dry it may be removed by washing the skin with luke-warm water, and then if the patches on the face or neck are very deep, the bleaching lotion may be forced into the skin by means of the negative electrode, … continuing the process until the skin is thoroughly reddened. This process, it should be understood, is only used for moth patch or chloasma, and would not be used in the ordinary treatment at all. Whether the lotion is used or not, however, the next step is the same and this consists … of forcing the whitening creme into the deeper tissues by means of the use of the red light of the radio bell. The eyes are better covered with cotton moistened in cold water or witch hazel, while this work is going on, in order to avoid any irritation.

After the skin has been sufficiently absorbed, finger massage may be given in the usual way and the treatment finished by applying a protecting coat of the vegetable powder. This process may be repeated several times a week with the greatest of benefit, though if the use of the paste seems at any time too severe, the use of the regular massage and a prolonged treatment with the negative electrode and the bleaching lotion may be effective.(Lloyd, 1907, pp. 88-89)

See also: Red Light, Blue Light and Iontophoresis

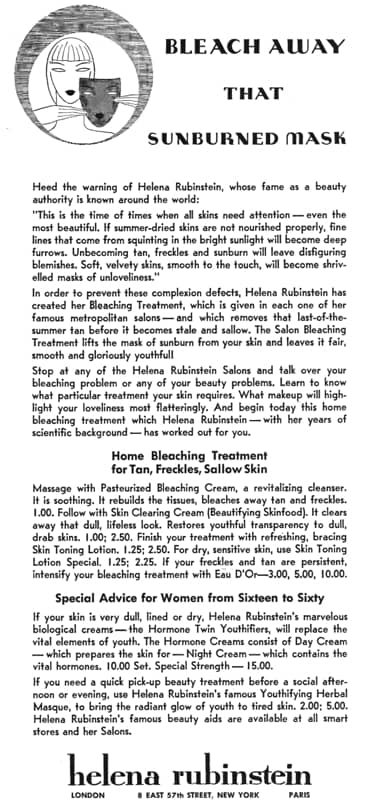

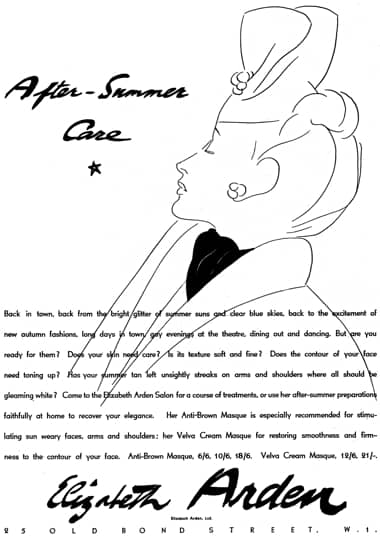

Many salons dispensed with mixing up hydrogen peroxide and used proprietary lines instead. Cyclax, Helena Rubinstein, Eleanor Adair, Elizabeth Arden and many others all had cosmetics to help whiten the skin.

Cyclax: Use Special Lotion more lavishly until summery complexions are back to normal. This lotion is applied thickly and allowed to remain on all night; then in the morning it is wiped away with cotton-wool dipped in cleansing lotion. It lifts impurities out of the skin, softens it and—most important at all—lightens by several shades. The treatment continued for a fortnight is calculated to make the skin white enough for the most feminine evening background.

Rubinstein: Special bleaching treatment. Eau d’Or. It is stroked on gently, because although it feels cool and refreshing at first it soon begins its bleaching action and bleaching naturally means a sensation of burning. After about ten minutes the bleaching cream is stroked in gently and the usual face massage is given.

Adair: Nile mud treatment is given to bleach and refine the skin after its too drastic baking. We are plentifully spread with the pack, which oddly enough, is very much the colour of the tan we are trying to remove. And behold! We do lose it.

Arden: Après l’Eté strong bleaching action and Venetian Masque to remove dead skin.(British Harper’s Bazaar, October, 1929)

Suntanning and bleaching

In the nineteenth century, sunlight was regarded as the enemy of lighter-coloured skin. Any activity that might lead to skin darkening had to be avoided if a perfect complexion was to be maintained. Towards the end of the nineteenth century this attitude began to change as women took up cycling, motoring and other outdoor pursuits. However, skin that was accidentally or incidentally tanned was frequently bleached to remove the tan once summer was over.

The bronze coloring has been so popular for the past few years that some of the faddists have spent much time in acquiring a coating, that cost[s] many dollars to remove. The desire to look weather-worn can usually be easily accomplished, for few people need more encouragement than an occasional outing on the river or driving through the country with no protection to the skin in the way of head covering or even a coat of powder. Once obtained it is extremely difficult to remove, and very frequently a thorough bleaching must be undergone before the brown shades vanish sufficiently to make the face presentable if light colors are to be worn.

(Lloyd, 1904, p. 98)

As the vogue for suntanning increased during the 1920s and 1930s many cosmetic companies found that sales of their skin bleaches began to decline.

Bleaching creams are not as popular as they once were when women favored lily white complexions instead of the outdoor tan which has won current favor.

(Chilson, 1934, p. 113)

However, many women still found bleaches useful when transitioning from a summer to a winter skin; tan lines and the rough, course texture of sun-bathed skin being major areas of concern.

Sun tan is very delightful when complete, but during the autumn months, when it slowly begins to fade, it is not becoming, and it is far better to resort to artificial means to remove it, than allow it to wear slowly off.

(Hanckel, 1937, p. 113)

See also the pamphlet: Golden Peacock Bleach Creme

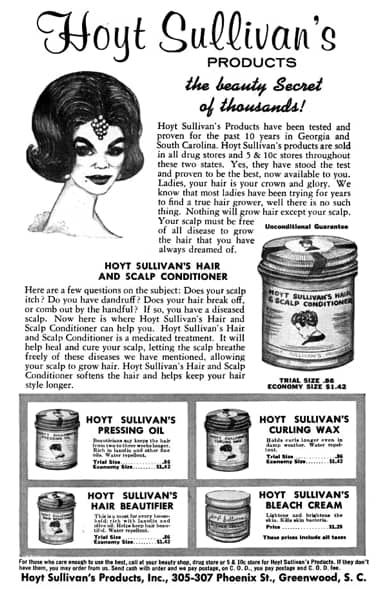

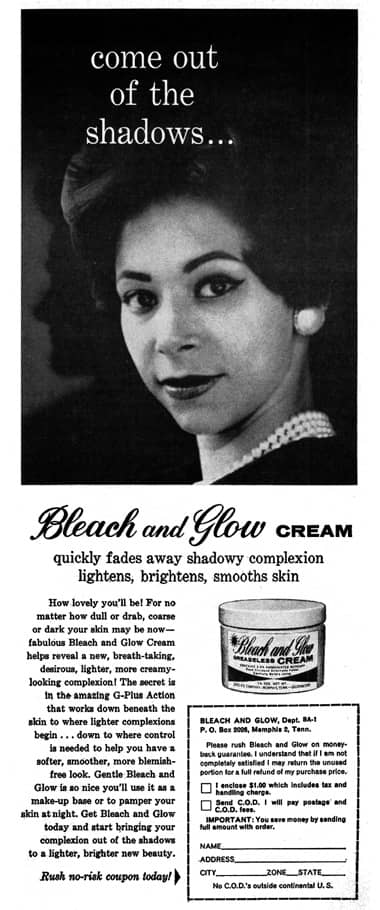

Along with the reduced demand from their traditional customers, the use of mercury compounds came under increased regulation, particularly in the United States. The amounts allowed in cosmetics were reduced and by the 1970s its use was banned altogether. The major cosmetic companies – who had shifted to promoting suntan and sunburn cosmetics as well as deeply-coloured make-up – were largely unaffected but many smaller brands suffered.

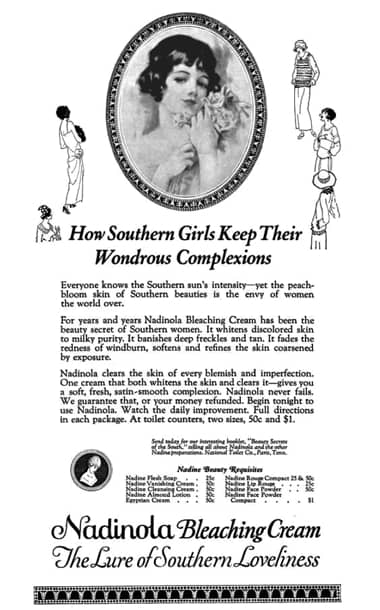

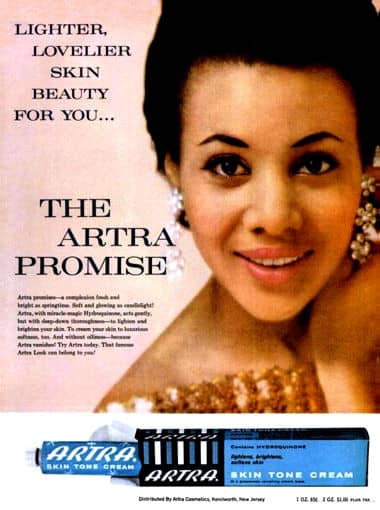

Depigmentation

As sales for their products began to decline, a number of smaller American brands – such as Hi-Ja Skin Lightener Creme, Mercolized Wax and Nadinola Bleaching Cream – began to concentrate more on sales to African American women. Though the percentage of ammoniated mercury in many of their products declined to well below 5%, a number of these skin bleaches managed to maintain or increase sales by targeting this market.

Also see the company booklet: Hi-Ja Beauty Aids

Even here the use of bleaches would eventually decline as depigmenting agents such as hydroquinone, which inhibits melanin production, came on the market in the 1950s.

Above: Esotérica Medicated Cream containing 2% Hydroquinone (Smithsonian).

Skin depigmenting (lightening) products soon largely replaced skin bleaches in the West but they were not without their problems and were later banned in many parts of the world. Unfortunately, they are still widely used, as are mercury-based skin bleaches which can still be found in some less-regulated parts of the world.

Updated: 4th August 2019

Sources

Alexander, P. (1975). Skin bleaches. In M. G. deNavarre The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd ed., Vol. IV) (pp. 1011-1027). Orlando, FA: Continental Press.

Blood, I. H. (1927). The cosmetiste: A handbook on cosmetology with special reference to the employment of electricity in the care of the hair, scalp, and face at the direction and under the supervision of W. M. Meyer (4th ed.). Chicago, Ill: The W. M. Meyer Co.

Chilson, F. (1934). Modern cosmetics. New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

Fletcher, E. A. (1901). The woman beautiful. A practical treatment on the development and preservation of woman’s health and beauty, and the principles of taste in dress. New York: Bretano’s Publishers.

Furlong, P. (1914). Beauty culture at home. A complete course in shampooing, facial and scalp massage, hair coloring, manicuring, chiropody, developing and reducing—also hundreds of reliable formulas for beauty preparations, including cold creams, skin bleaches, liquid and dry powders, rouges, depilatories for removing superfluous hair, shampoo mixture, hair tonics and restorers, curling fluids, bust developing, reducing, remedies for wrinkles, pimples, blackheads, freckles, liver spots, sunburn, eyes, mouth, hands, feet, exercises, diet and miscellaneous valuable hints—as taught at Paulette School. Washington: Author.

Hanckel, A. E. (1937). The beauty culture handbook: A modern textbook of beauty culture and hairdressing for beauty parlour assistants and ladies desirous of practising self-treatment. London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd.

Lloyd, E. (1907). The skin. Its care and treatment (3rd ed.). Chicago: McIntosh Battery & Optical Company.

Mixter, M. (1910). Health and beauty hints. New York: Cupples & Leon Company.

Oleson, C. W. (1903). Secret nostrums and systems of medicine: A book of formulas (10th ed.). Chicago: Oleson & Co.

Ozier P. (1957). Skin lighteners and bleach creams. In E. Sagarin (Ed.). Cosmetics: Science and technology (pp. 213-221). New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc.

Shelvin, E. J. (1972). Skin lighteners and bleach creams. In M. S. Balsam & E. Sagarin (Eds.). Cosmetics: Science and technology (2nd. ed., Vol. 1) (pp. 223-239). New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Sloane. (1934). Neck massage—Why it’s necessary—How it’s done. The Hairdresser and Beauty Trade, April 14, 3(6), 12.

Sloane. (1934b). How to arrange a special summer beauty service. The Hairdresser and Beauty Trade, June 23, 3(17), 11.

The Countess C—. (1901). Beauty’s aids or how to be beautiful. Boston, MA: L. C. Page & Company.

Verni, M. (1946). Modern beauty culture (2nd ed.). London: New Era Publishing.

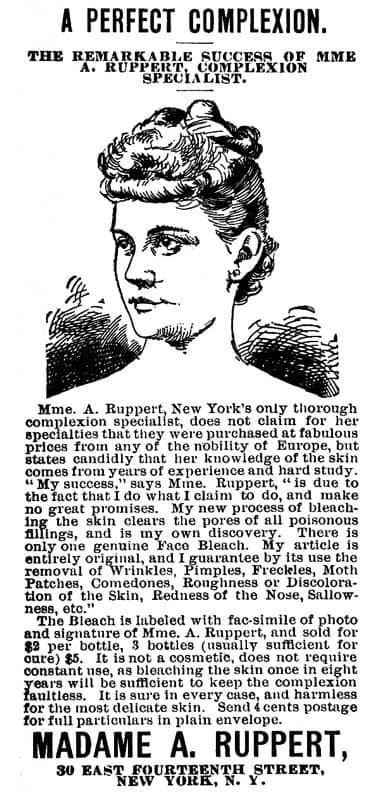

1890 Madame A. Ruppert face bleach. Made from corrosive sublimate, tincture of benzoin and water.

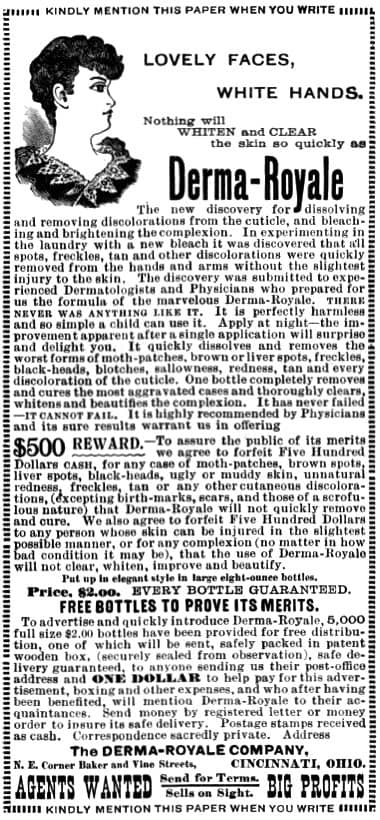

1892 Derma-Royale.

1909 Dioxogen. A commercial form of hydrogen peroxide.

1916 Cyclax Clenzene recommended for removing neck stains created by fur dyes.

1923 Balm-O-Lem.

1924 Kremola. Made from ammoniated mercury and zinc stearate in petrolatum-based cream.

1924 Nadinola Bleaching Cream.

1928 Dorothy Gray treatments after a summer vacation.

1928 Black and White Peroxide Vanishing Cream.

1929 Dearborn Mercolized Wax.

1930 Golden Peacock Bleach Creme.

1933 Helena Rubinstein Pasteurized Bleaching Cream.

1938 Elizabeth Arden Anti-Brown Masque.

1961 Hoyt Sullivan’s Bleach Cream.

1962 Bleach and Glow Cream with ammoniated mercury.

1963 Artra Skin Tone Cream containing hydroquinone.