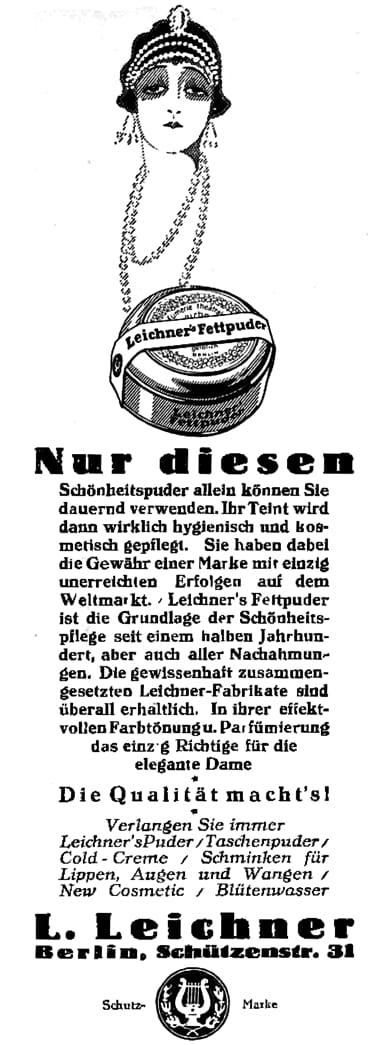

Fettpuders (Fat Powders)

In an article published in ‘Chemist and Druggist’ (1931), H. Stanley Redgrove [1887-1943] explained why theatrical powders differed from more general forms.

Theatrical powders are quite different from the usual run of face powders intended for everyday use. For application over a grease-paint make-up, powders should be used which posses a sufficient degree of transparency not to hide the colouring and should themselves be tinted a shade which will blend with this.

(Redgrove, 1931, p. 590)

A good example of a transparent theatrical powder was Leichner Blending Powder. It only came in one yellowish shade which did not change the underlying colour of the greasepaint it powdered down. Not all theatrical powders were like this. Max Factor Supreme Face Powder used to powder down Max Factor Grease Paint was more opaque and came in different shades that had to be matched to the greasepaint. However, Max Factor products were not widely used on the British stage in 1931.

See also: Max Factor (1930-1945)

To make powders transparent, they were formulated with a high proportion of translucent talc and low levels of opaque materials such as starch or zinc oxide.

parts Talc, purified 70 Maize starch 20 Zinc oxide 10 (Redgrove, 1931, p. 590)

Powders made with high levels of talc have a greasy feel and Redgrove notes that they were sometimes known in British theatrical circles as ‘fettpuders’, a German term that probably came from Leichner, the biggest supplier of theatrical make-up in Britain at the time. However, Redgrove suggests that this term should be restricted to powders that were really ‘fatty’; i.e., those that contained some sort of oily or greasy material added to make the powder more adherent. Winter (1932) suggests this could be done by adding a small amount of vaseline oil.

Fettpuder gm Talcum 3000 Rice flour 800 Zinc white 500 Powder perfume 60 In order to make a fat powder really sticky and “fat”, you add about 1 to 2% of the finest white vaseline oil to the powder mixture. The mass then has to pass through the screening machine several times so that the oil is optimally distributed.

(Winter (trans), 1932, p. 337)

A variety of materials could be used to make a powder ‘fat’ including lard, tallow, cocoa-butter, lanolin, paraffin and cold cream. Simply rubbing the oily/greasy material into the powder was used in many cases. An alternative method was to dissolve the oily/greasy material in a solvent and then soaking a powder in the solution before drying and mixing it with the remaining ingredients.

Lanolin Powder (Fettpuder—Fat Powder) parts Lanolin, Anhydrous 25 Italian Talc 850 Magnesium Carbonate 125 Floral Oil to perfume as desired. The lanolin is first dissolved in ether and this solution is then mixed with the magnesia. After drying, this mixture is finely ground and gradually mixed with the talc.

parts Lanolin, Anhydrous 50 Boric Acid 50 Wheat Starch 450 Italian Talc 480 Oil of Wintergreen 10 drops Aromatic spirits 10 drops [T]he lanolin is first dissolved in 200 parts of ether and then mixed with the starch. After drying, the other ingredients are thoroughly mixed in and the finished product finely pulverized.

(Schanzenbach, c.1925, p. 96)

Early theatrical fettpuders

The earliest records I have for fat powders are from Germany in the 1870s. The were made by a number of firms there including Leichner. The 1870s also saw the introduction of greasepaint which became available in Germany and elsewhere after 1873 when Johann Ludwig Leichner [1836-1912] established the Leichner company to manufacture it.

Greasepaint helped players cope with the brighter gas lighting introduced into theatres after 1840. It covered better than powder, gave actors more control over their make-up, and was largely unaffected by perspiration.

See also: Greasepaint and Leichner

Due to their increased adherence, fat powders did not have to be applied over greasepaint so could be used as an alternative. Leichner Fettpuder came in the same shades as Leichner Greasepaint and harmonised with other forms of Leichner theatrical make-up. This suggests that it was used by players who disliked using greasepaint but wanted a powder that resisted perspiration. Redgrove suggests that fettpuders may also have been useful in daylight performances when only a light make-up was required.

Actresses were probably the main customers for theatrical fat powders. Unlike male actors who could thrill audiences by dramatically changing their make-up for character parts, those same audiences often expected an atractive actress to look the same no matter what part she was playing, reducing their need for greasepaint.

Of course the broader characteristics of male physiognomy admit of more varied and more distinct “make-up.”

We look for familiar features in a handsome actress, and are disappointed to see them distorted even for the sake of character.(Fryers, c.1904, p. 65)

Unfortunately, as most early stage make-up manuals were written by men using greasepaint, I have been unable to locate any definitive records on how widely theatrical fat powders were used or who made up with them. However, there must have been an ongoing market as Leichner continued to include them in its artists catalogues in a full range of shades well into the twentieth century.

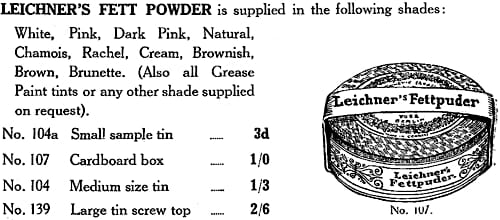

Above: c.1926 Fettpuder listing from an English L. Leichner catalogue. It was available in all Leichner greasepaint tints.

See also: Leichner Artists Catalogue (c.1926)

Other fatty powders

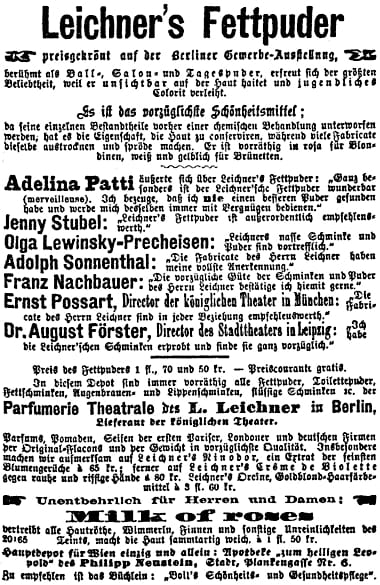

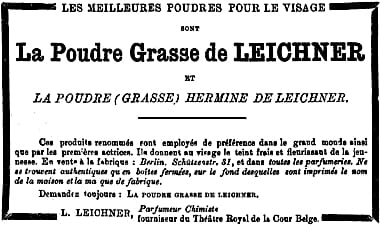

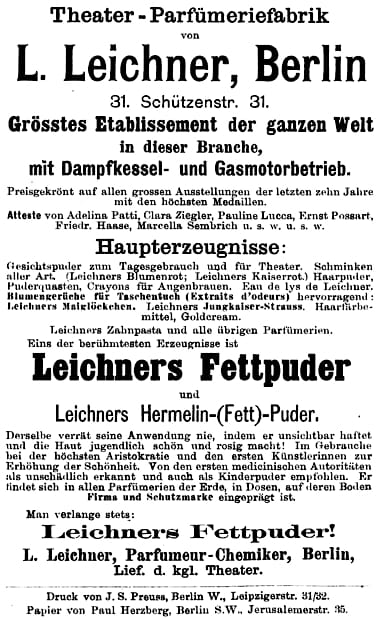

Fatty face powders (fettpuders, poudres grasses) moved from the stage into the general population very quickly with actresses leading the way. Leichner Fettpuder was being suggested as a ball, salon and day powder no later than 1878 and the company later added a second fat powder into its range – Hermelin Fettpuder.

Before vanishing creams became widely available after 1900, women who had problems getting face powder to stick, had to use cold cream, vaseline or something similar as a powder base. The stickiness of fat powders made them more attractive to these women than regular powders that claimed to be adherent but often required frequent retouching.

See also: Vanishing Creams

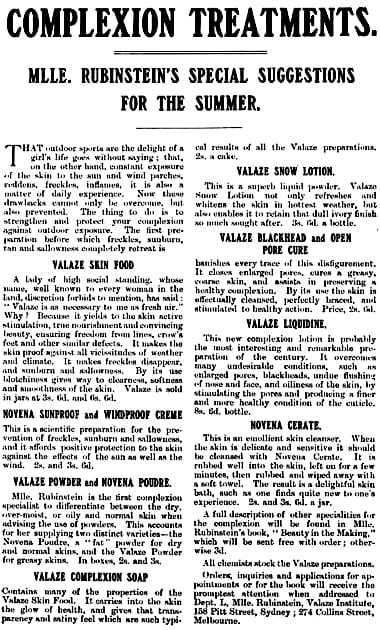

Powder adhesion was more of a problem for women with a ‘dry’ skin, dry meaning a skin that was low in natural oils. Helena Rubinstein [1872-1965] recognised this and recommended a fat powder for women whose skin was low in oil. Her Novena Poudre, specially prepared for dry skins, was available in Australia by 1909.

Some Novena Poudre should always be dusted on afterwards, as this is a ‘fatty’ powder, containing a considerable quantity of an emollient in its composition, and should be used for dry skins exclusively.

(Helena Rubinstein, c.1915, p.12)

See also: Helena Rubinstein and Dry Skin Treatments

However, if a face powder was being used to absorb perspiration, reduce shine, or apply a fragrance, then a conventional powder would suffice.

Body and baby powders

The introduction of vaselines and lanolin derivatives into powders in the later part of the nineteenth century saw a number of commercial and medicinal fat powders introduced for use on various parts of the body. For example, medicinal powders could be created by adding an oil-soluble medication into the oil used in the fat powder; adding lanolin to a powder could help protect hands from chapping in cold dry conditions; and incorporating petroleum derivatives in to a powder produced a suitable baby powder.

Lanolin Powder [for chapped hands].—Lanolin is dissolved in ether, and this solution mixed with magnesium carbonate to a stiff mass, and this is rubbed down with talc and starch.

Pharmaceutical Journal, June 2, 1900, p. 619)

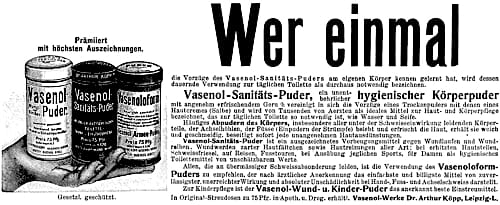

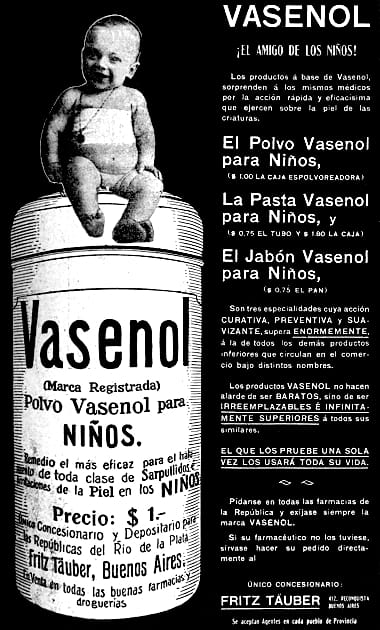

Above: 1912 Vasenol was a type of petrolatum developed in Germany that could be incorporated into liquids and powders. It was used to make a range of body and baby powders including a foot powder used by the German army during the First World War.

Cold cream powders

In the twentieth century the most popular fat face powder used cold cream as the oily/fatty material. Winter (1942) includes a simple recipe for one.

Body Fettpuder gm Talcum 650 Zinc white 350 Cold Cream 20 The cold cream is melted and thoroughly rubbed in with part of the powder. This is then sieved and mixed with the rest of the body powder.

(Winter (trans), 1942, p. 280)

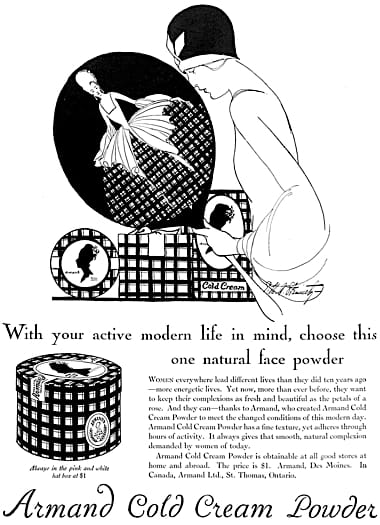

The most commercially successful cold cream powder was probably Aida Complexion Powder introduced by Armand into the United States in 1918. Unlike Helena Rubinstein’s Novena Poudre it was not advertised initially as a powder specifically for dry skin types. Later known as Armand Cold Cream Powder it came in White, Cream, Pink, Brunette, and Tint Natural shades.

See also: Armand

It was very successful in America in the 1920s and 1930s but this may have been more to do with Armand’s merchandising policy rather than any of its intrinsic benefits.

First posted: July 27th 2023

Sources

Czetsch-Lindenwald, H. V., & Schmidt-La Baume F. (1944). Salben, puder, externa: Die äusseren heilmittel der medizin. Berlin: Spinger-Verlag.

Fryers, A. (c.1904). A guide to the stage London: R. A. Everett & Co. Lyd.

Hartop, A. (1934). Make-up for the body and limbs. In H. Downs (Ed.) Theatre and Stage (pp. 267-270). London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd.

Helena Rubinstein. (c.1915). Beauty in the making [Booklet]. UK: Author.

Mann, H. (1904). Die moderne parfümerie. Augsburg: Verlag für Chemische Industrie.

Redgrove, H. S. (1931) Theatrical powders. The Chemist and Druggist, November 15, 590.

Redgrove, H. S., & Foan, G. A. (1930). Paint, powder and patches: A handbook of make-up for stage and carnival. London: William Heinemann.

Schanzenbach, J. (c.1925). Practical use of raw materials in the beauty parlor. New York: J. Schanzenbach & Co., Inc.

Winter, F. (1932). Die moderne parfumerie (4th ed.). Vienna: Springer-Verlag.

Winter, F. (1942). Handbuch der gesamten parfumerie und kosmetik (3rd ed.). Vienna: Springer-Verlag.

1872 B. Langwisch Fett-Puder (Germany).

1877 Jon. Nikolodi Fett-Puder (Germany).

1879 Leichner Fettpuder (Germany).

1888 La Poudre Grasse de Leichner and La Poudre (Grasse) Hermelin de Leichner (France).

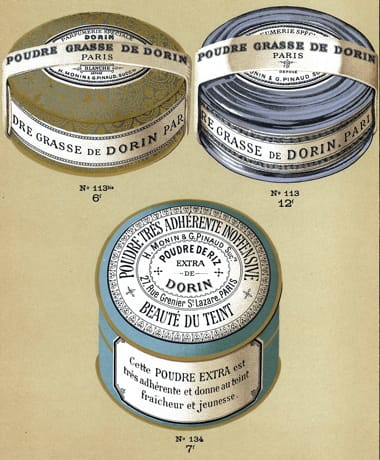

1893 Poudre Grasse de Dorin and Poudre de Riz Extra de Dorin (France). The Poudre Grasse only came in the same four shades as the Poudre de Riz so was probably sold as a general, not a theatrical, make-up.

1896 Leichner Fettpuder and Hermelin-(Fett)-Puder.

1907 Polvo Vasenol baby powder (Buenos Aires).

1909 Helena Rubinstein Complexion Treatments including Novena Poudre for dry skin types.

1924 Leichner Fettpuder.

1927 Jontell Cold Cream Face Powder.

1928 Armand Cold Cream Powder.

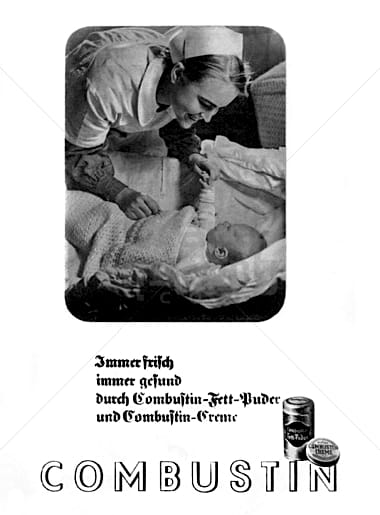

1941 Combustin Fett-Puder baby powder.