Bourjois (post 1930)

Continued from: Bourjois

By 1931, Bourjois had made Evening in Paris available across the world and it became the leading Bourjois series by 1934. Its popularity helped insulate the company from the worst economic effects of the Great Depression.

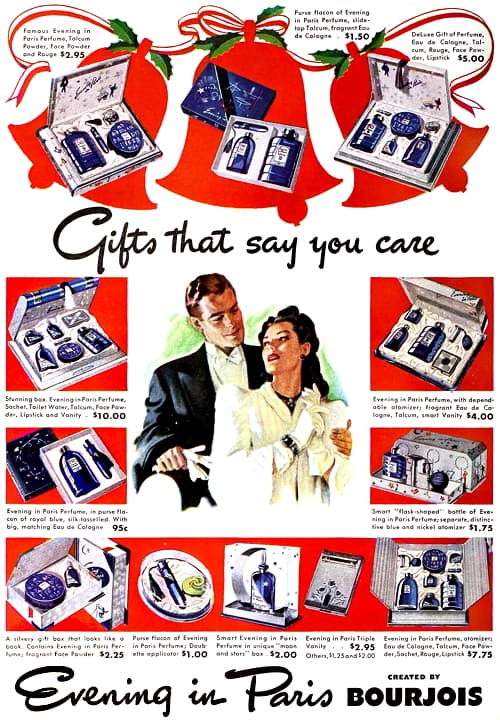

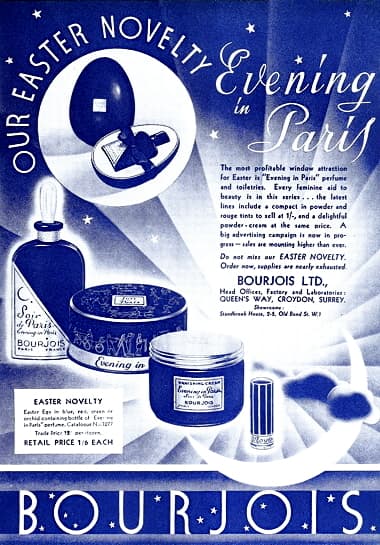

The Evening in Paris range included all the usual items found in an extended Bourjois series including Evening in Paris Eau de Toilette, Bath Crystals, Face Powder, Dusting Powder, Compact, Lipstick, and Rouge. Demand peaked towards Christmas and the company introduced new gift sets, novelties, and coffrets at the end of the year specifically for this market in a range of prices to suit different budgets.

Above: 1940 Bourjois Evening in Paris Christmas suggestions.

By the 1930s, the development of cosmetics at Bourjois was primarily driven by the creation of new fragrances rather than new formulations. Each new perfume was developed into a series, its extent depending on the popularity of the fragrance. With few exceptions, all the cosmetics in each new range had already appeared in previous series so there was little need for innovation in formulation. Although profitable, this strategy would prove to be unsustainable in the long term.

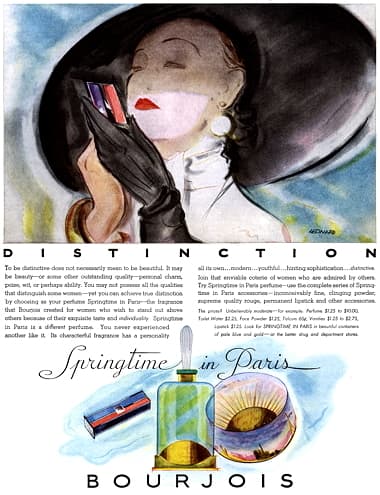

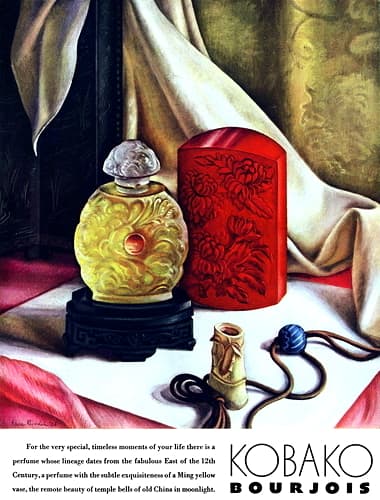

New perfume series released by Bourjois during the 1930s in the United States included Springtime in Paris (1932), Flamme (1935), Kobako (1936) and Mais Oui (1939). Springtime in Paris and Kobako were released in France in the same year as America but I can find no record of Mais Oui going on sale in France in the 1930s or any of these new fragrances being available in Britain or the Dominions before the Second World War except for Flamme.

Springtime in Paris and Mais Oui appear to have been the most successful of the new perfumes released in the United States and their series were larger than the other new entrants. However, neither range was as extensive as Evening in Paris which continued to have new cosmetics added to it through the 1930s. Given the product overlap between the cosmetics and toiletries in the Evening in Paris series and those of other Bourjois fragrances I will largely ignore the later additions.

Also largely missing is any mention of eye make-up, and nail polish. Bourjois did make these but there are few records of their range or development before 1960 which is where my interest ends.

United States

As the Great Depression deepened in the 1930s, the American Federal government responded to local pressure and tried to protect its local industry through the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (1930). This raised import duties on a range of products by an average of 20% which encouraged many companies to increase local production.

Bourjois was already making some products in the United States and had moved its manufacturing base to Rochester after its merger with Woodworth in 1929. Bourjois consolidated and expanded its manufacturing there in 1931 after purchasing the old Premo camera plant at 45 South Street, Rochester from Eastman Kodak in 1930. Most of the company offices were also moved to Rochester but Bourjois continued to maintain its showrooms at its New York address.

Bourjois was also affected by another piece of Federal legislation, the Revenue Act of June, 1932 which included a tax on cosmetics of up to 10%. Bourjois responded to the new tax in August, 1932 by reorganising its business to try and take advantage of a quirk in the American law.

The new tax was levied on manufacturers so Bourjois separated the distribution part of its business from the manufacturing side and then paid the tax on the lower price Bourjois Inc. levied its newly created distributor, Bourjois Sales Corp. for the products it manufactured rather than the higher price Bourjois Sales charged for these goods. This lowered the amount of tax the company paid to the Federal Government.

The Federal Bureau of Internal Revenue viewed Bourjois’ reorganisation as an illegal tax-avoidance strategy and took Bourjois to court. After appeals, the case was eventually resolved in 1936 with the judge ruling in favour of the government. A number of other American cosmetic companies, such as Elmo, Marinello, and Lady Esther had introduced a similar tax-reduction strategy so Bourjois became a closely watched test case.

See also: Elmo, Marinello, and Lady Esther

Another problem for the American company that arose in the 1930s involved its face powders. Like other American cosmetic companies, Bourjois became concerned when Lady Esther began its ‘Bite Test’ campaign in 1935. This suggested that women grind a pinch of their face powder between their front teeth to see if it contained ‘grit’. Most other powders then on the market, including Bourjois’ were not fine enough to pass the test.

See also: The Bite Test

Bourjois had a number of face powders in the American market in 1935 including Java, and Manon Lescaut, two of Bourjois’ earliest face powders; Karess, and Fiancee which had been added to Bourjois through the merger with Woodworth in 1929; and the newer entrants such as Evening in Paris, Springtime in Paris, and Flamme.

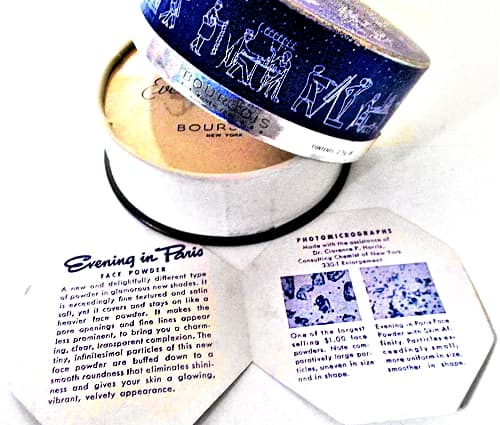

Worried particularly about sales of its Evening in Paris Face Powder, Bourjois responded to the ‘Bite Test’ with its ‘Back-of-hand-test’. This claimed that its triple silk-sifted Evening in Paris Face Powder softened contours as well as the skin, giving its powders ‘Skin Affinity’. To emphasise the point, some Bourjois advertisements of the period included photomicrographs of face powder particles to show that they were small and smooth.

Above: Evening in Paris Face Powder with booklet.

The first to combine the best features of both superfine, superlight face powders and heavier types. A completely, new texture in which each particle of powder is from two to three times smaller than those in many other popular types; also much more uniform in size, much smoother in shape.

(1939 Bourjois advertisement)

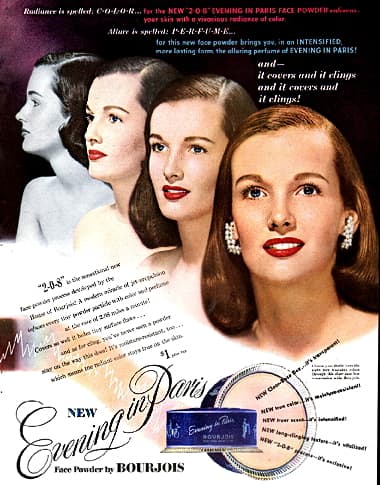

In 1936, Coty responded to Lady Esther’s ‘Bite Test’ by introducing its highly successful ‘Air Spun’ Face Powder which used air-powered micronisers to produce smaller, more even powder particles. This may have led Bourjois to describe its popular Manon Lescaut Face Powder, Peaches Powder, and Peaches and Cream Powder as having a ‘Zephyr Texture’. However, Bourjois would not get access to a technology similar to that used by Coty until 1947 when it introduced its 2-0-8 Evening in Paris Face Powder.

See also: Coty “Air Spun” Powder

Products

New cosmetics added to the Evening in Paris series in the United States during the 1930s included Evening in Paris Eau de Cologne (1931), Bubbling Bath Essence (1938), and Evening in Paris Trio Lotion (1939), the last item being a novel product for Bourjois.

Evening in Paris Trio Lotion was a type of all-purpose cream, a cost-cutting cosmetic that became popular in the United States during the Depression. Packaged in a ribbed bottle, it was advertised as a three-way beauty treatment – cleanser, powder base, and skin softener. As far as I can tell, it was only manufactured in the United States and was only included in the Evening in Paris series.

Trio Lotion: “[A] fragrant, velvety lotion that gives your skin a three-way beauty treatment—all at one time! Make it a daily ritual to use it morning and evening for quick cleansing, and as a powder base . . . use it nightly as a skin softener . . . apply it before and after exposure to wind, water and sun . . . and you’ll love the marvelous results.”

See also: All-Purpose Creams

Bourjois make-up shade ranges remained limited. Evening in Paris Lipstick, which was given a new case in 1931, was only available in six shades – Dark, Medium, Light, Brilliant, Orange, and Coral – as was Mais Oui Lipstick – Medium, Light, Brilliant, Currant Rose, Cerise, and Koral – when it was released in 1939. Unfortunately, I have no information on powder shades in America except for Evening in Paris which came in Naturelle, White, Rachel, Rachel No. 2, Rose Orchid, Rose Indian, and Sun Blush in 1938.

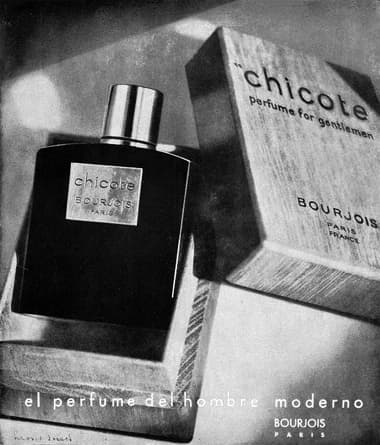

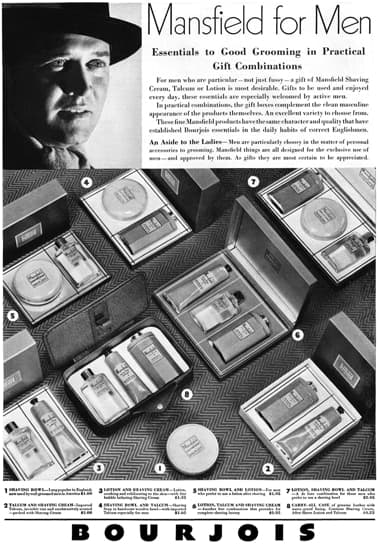

Worth mentioning is Bourjois’ Mansfield range of men’s shaving toiletries. Introduced in 1936, the line consisted of Mansfield Shaving Soap, Shaving Cream, Talcum, and After Shave Lotion. Bourjois had made shaving products well before this but this range appears to have been specifically developed for Father’s Day which American stores began to heavily promote in the 1930s to help boost flagging sales. Mansfield was not Bourjois’ first fragrance created for men; Chicote was available in the Spanish speaking world by 1935.

France

Wertheimer Frères, the French company that controlled Bourjois, Barbara Gould and Chanel, began the new decade by transferring their headquarters from 60-62 Rue d’Hauteville to 43 Avenue Marceau, Paris in February, 1930. However, the French headquarters of Bourjois continued to reside at 60 Rue d’Hauteville until at least 1932.

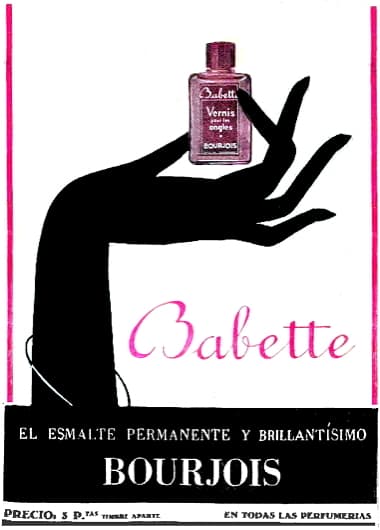

Soir de Paris became available in France and other parts of Europe in 1929, when conditions were economically very buoyant and initially Bourjois used Babette, the fictional character Bourjois had created in 1924 to promote Mon Parfum and the Fards Pastels, to promote it.

Advertisements featuring the activities of Babette were discontinued in 1930, presumably because Bourjois thought that her persona and activities were too frivolous for the more sober economic conditions then prevailing. However, as noted later, this was not the end of Babette.

Products

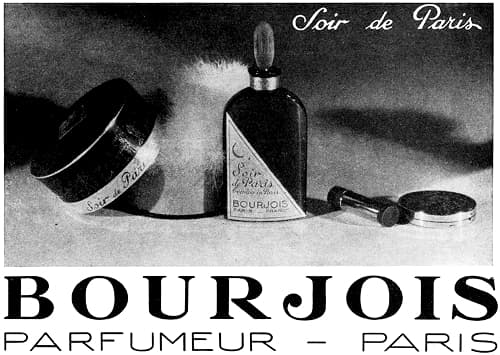

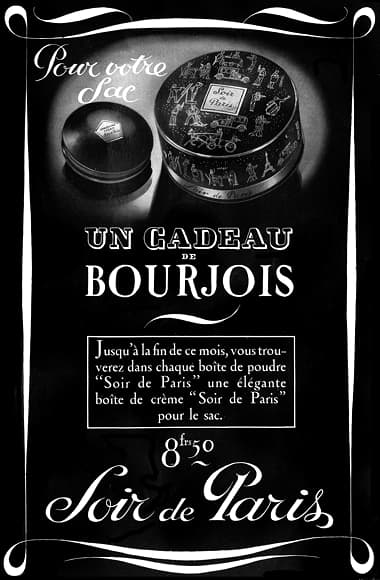

Soir de Paris replaced Mon Parfum as the leading French series of the 1930s. Items in the Soir de Paris series in France included Poudre Soir de Paris, Rouge à Lèvres Soir de Paris, and Compact Soir de Paris, with Crème Soir de Paris, a vanishing cream similar to that produced for Mon Parfum, added in 1931. Other items in the range that I know of were Eau de Cologne Soir de Paris, Savon Soir de Paris, and Brilliantine Soir de Paris.

Above: 1930 Bourjois Soir de Paris series.

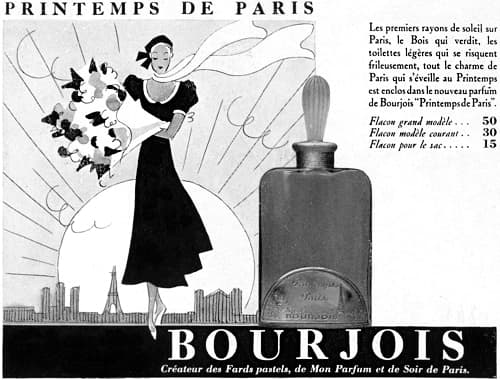

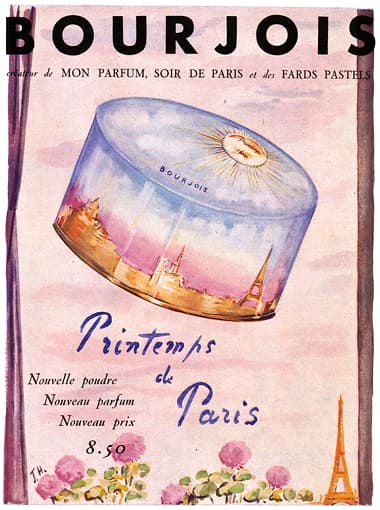

As mentioned earlier, the Soir de Paris was joined by other fragrances in the 1930s including Printemps de Paris and Kobako which came out in the same year as their American versions. Much was made of the fact that Poudre Printemps de Paris only cost 8.50 Francs.

Above: 1933 Bourjois Printemps de Paris.

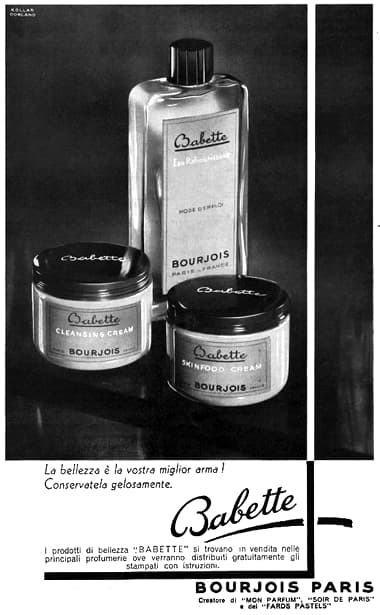

Another adjustment made by Bourjois in France to the general economic downturn was the introduction of a new budget line. Released in 1931, the Produits de Babette were described as effective, simple, and inexpensive. There were products for oily (peaux grasse) and dry (peaux sec) skin types and suggestions for day and night regimes.

Above: 1932 Babette night and day treatments (Spain).

The skin-care routine followed the standard practice of cleansing, nourishing, and protecting the skin. Products included: Eau Astringent de Babette, Astringent Cream de Babette, Lait de Beauté de Babette, Cleansing Cream de Babette, Skin Food de Babette; Eau Tonique de Babette, Eau Rafraichissante de Babette, and Protection Cream de Babette. I have found no record of the range appearing in Britain or the United States.

The use of English terms like Cleansing Cream, Skin Food, and Protection Cream, followed Bourjois’ previous use of names like Cold Cream and Vanishing Cream. Bourjois’ major cosmetic brand, Barbara Gould, also labelled its products sold in France with English names.

I have no record of the Produits de Babette being extended into make-up but as the range included nail polish, I do not rule it out. However, the life of the range was short. Like Mon Parfum, it did not survive the Second World War.

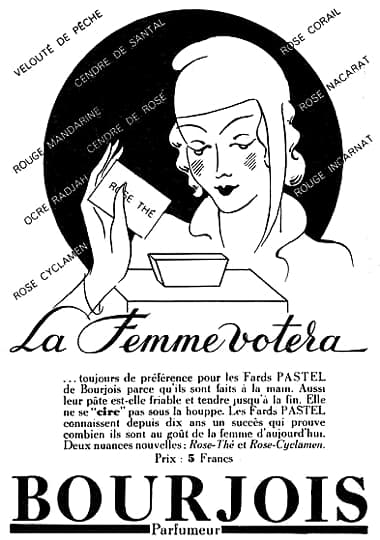

Bourjois continued to heavily advertise its Fards Pastel in France during the 1930s and added new shades including Rose Thé and Rose Cyclamen (1935). Other shades then in circulation included Cendre de Roses, Rouge Mandarine, Cendra de Santal, Ocre Radjah, Velouté de Peche, Rose Nacarat, Rouge Incarnat, and Rose Corail but this list is not complete.

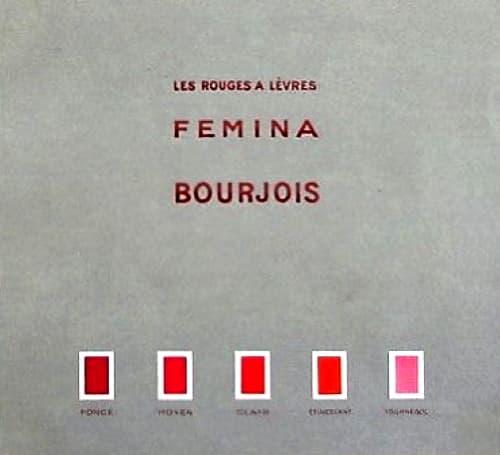

There were also some modest increases in the shade range of Bourjois lipsticks in France. Raisin Mon Parfum (1928) had come in four shades but Raisin Femina (1931) came in five tints.

Above: Shade chart for Rouges à Lévres Femina. From left to right: Foncé, Moyen, Clair, Étincelant, and Tournesol. It is possible that the Mandarine shade was added to Femina lipsticks by 1934 as it had appeared in Bourjois lipsticks elsewhere in the world by then.

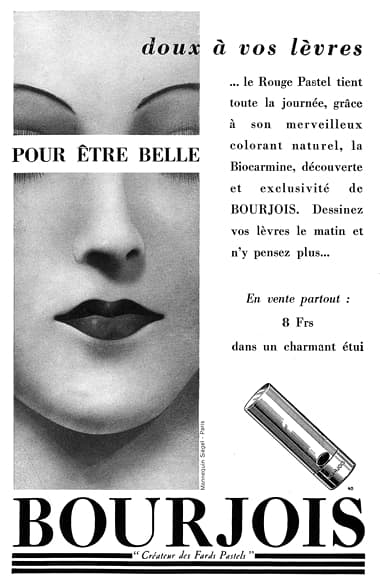

In 1933, Bourjois began heavily advertising its Clair (Medium) lipstick shade as containing a new natural colourant it called Biocarmine. The lipstick appears to have been an indelible so the colourant must have been more than carmine. Its introduction may have been a belated response to the new indelible lipstick introduced by Coty earlier in the decade.

Information on the shade range of Bourjois face powders during the decade is also largely missing. In 1940, Poudre Soir de Paris came in Pêche, Rose, Ocrée Chair, Ocre Foncé, and Soleil but there is evidence that the shade ranges of other face powders such as Mon Parfum and Manon Lescaut was more extensive.

Above: Italian Mon Parfum powder box listing a wide range of shades: Blanche, Rose I, Rose II, Pêche, Naturelle, Rachel, Rachel Foncé, Ocrée Chair I, Ocrée Chair II, Ocrée I, Ocrée II, Ocre Foncé, and Ocre Soleil.

Colour coordination

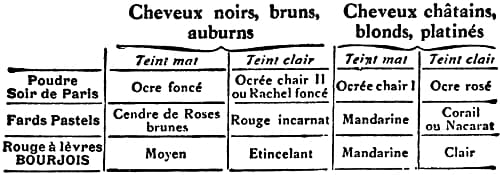

When Bourjois talked about harmonising make-up it was generally referring to avoiding scent clashes. However, there are some rare instances in France when Bourjois provided information on colour coordinating its powder, rouge and lipsticks.

Above: 1937 Suggested colour coordinated powder, rouge and lipstick shades for women based on hair colour.

Britain

Like the United States, the British Government also raised import tariffs to protect local industry in the early years of the Depression, passing the Import Duties Act (1932) which put a 10% duty on imported goods. Britain also went off the Gold Standard in 1931 which devalued the Pound Sterling. Both developments increased the cost of imports and made local manufacturing more attractive.

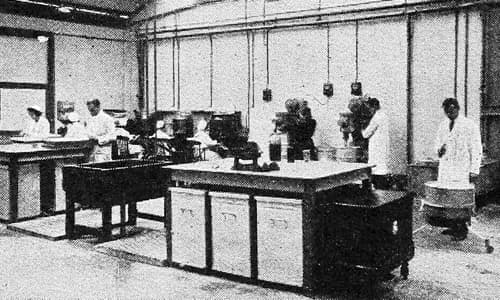

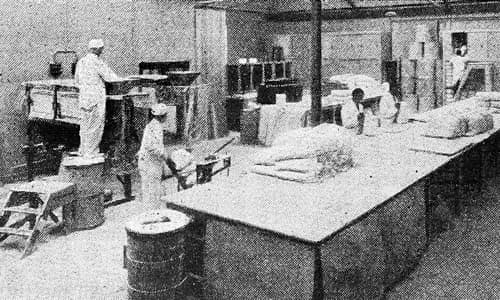

Bourjois had been manufacturing in Britain since at least 1926 with a factory at 71-73 Carter Lane, London and a soap factory at River Plate Wharf, Upper Ground Street. It began building larger facilities at Queen’s Way, Croydon late in 1931, completing the move of its business there in 1934, except for a showroom in London at Standbrook House, 2-5 Old Bond Street. The new factory site was next to Croydon Airport which had unfortunate consequences for Bourjois during the Second World War.

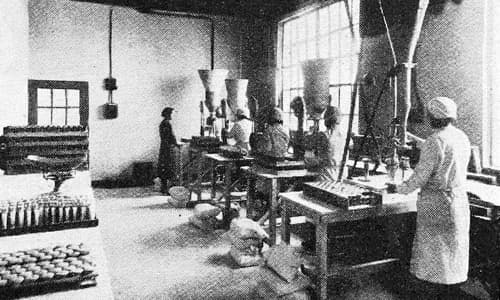

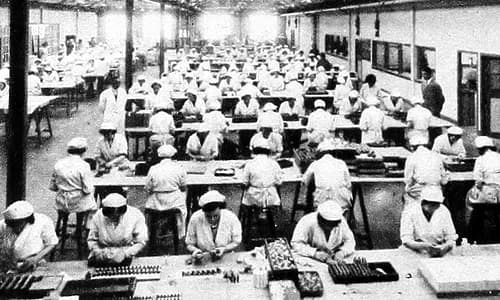

Above: 1934 Mixing creams at Croydon.

Above: 1934 Mixing and blending powders at Croydon.

Above: 1934 Filling face powder boxes at Croydon.

Above: 1934 Finishing department at Croydon.

See also: Toilet Soaps (c.1934).

Products

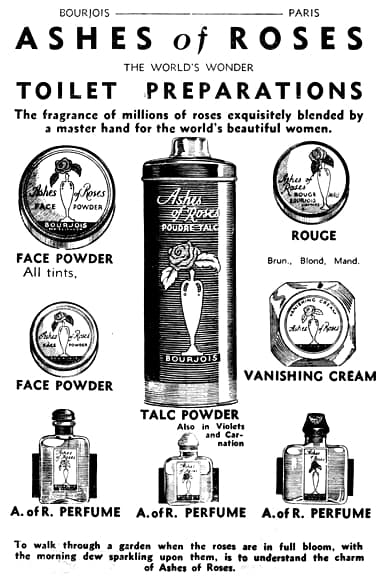

Bourjois continued to sell cosmetics from their various Ashes series in Britain and the Dominions in the 1930s but dropped the prices for many lines. The most important Ashes series continued to be Ashes of Roses and new products were added to the range in the 1930s including: Ashes of Roses Bath Crystals (1930); Ashes of Roses Powder Shampoo, Hair Cream, and Wave Setting Lotion (1932); and Ashes of Roses Powder Cream (1933).

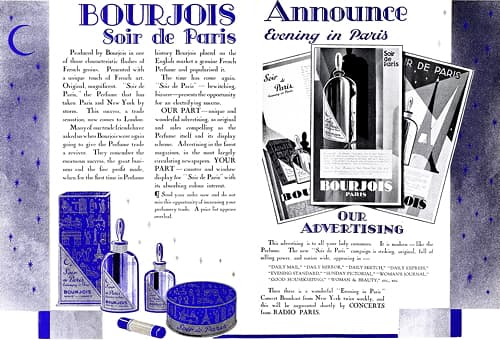

As elsewhere, the Evening in Paris series became the primary focus of the company in Britain in the 1930s, initially promoted in Britain as Soir de Paris. British shade names tended to follow those used in France rather than America, a trend the company had established in the 1920s. The initial range consisted of Soir de Paris Perfume, Face Powder, Compacte Powder (in a nickel case), Lipstick, Talcum Powder, Bath Dusting Powder, and Friction Lotion. As well as extensive advertising in print, the line followed the strategy used in America and France and was promoted over the airwaves using Radio Paris.

Above: 1930 Trade advertisement for Soir de Paris (UK).

As previously noted, the Springtime in Paris and Mais Oui series were not introduced into Britain before the war and this may partially explain why the British Evening in Paris series, like the British Ashes of Roses series, appears to have been more extensive than the Evening in Paris range sold in the United States.

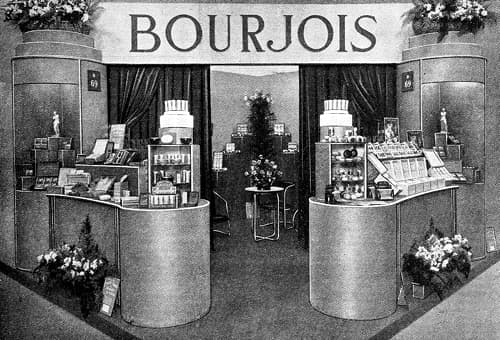

Above: 1932 Bourjois display at the British Industries Fair.

Additional Evening in Paris lines added in Britain during the 1930s included: Evening in Paris Toilet Soap, and Vanishing Cream (1931); Solid Brilliantine, Shampoo Powder, Hair Cream, Cold Cream, and Toilet Soap (1932); Evening in Paris Powder Cream (1933); Skin Freshener, Complexion Milk, Astringent Lotion, and Cleansing Cream (1934); Wave Setting Lotion (1935); Eau de Cologne (1936); and Rouge (1938). Clearly most of these were similar to lines already developed for Ashes of Roses.

Of particular note is the Evening in Paris Powder Cream. I have only found evidence for it in Britain and the Dominions before the war but it seems likely that it was available elsewhere, especially France. Like the earlier Ashes of Roses Powder Cream it came in Natural (Naturelle) and Rachel (Rachelle) shades with Sun Tan (Ocree Soleil) added in 1934. In 1938, the company began selling it in tubes, something it had previously done for Ashes of Roses Cold Cream, and Vanishing Cream in 1930.

Bourjois continued to sell a wide range of rouges in Britain and the Dominions during the 1930s. The Ashes of Roses Rouge only came in Rosette Brune, Rosette Blonde, and Mandarine shades but the company sold at least seventeen other shades of rouge in Britain in the 1930s. Those that I have evidence for are Rouge Incarnat, Rouge Groseille, Rouge Corail, Vert Opelia, and Cendres de Violettes.

Lipsticks shades sold by Bourjois in Britain followed those in France. For example, Femina Lipsticks (1932) also came in five shades but Bon Goût Lipsticks (1938) increased the range to six – Fonce, Moyen, Clair, Etincelant, Mandarine, and Tournesol (Dark, Medium, Light, Sparkling, Tangerine, and Sunflower).

As elsewhere, information on Bourjois powder shades is largely missing. I have a record that Evening in Paris Face Powder came in eleven shades by 1937 but the only shades I know of were: Naturel, Rachel, Medium Rachel, Deep Rachel, Peach, Peach-Tan, and Sun-Tan.

War

By the time war broke out in September, 1939, Bourjois had factories operating in Britain, America, Australia, Canada, Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Columbia, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Mexico, Norway, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, Rumania, Poland and Cuba.

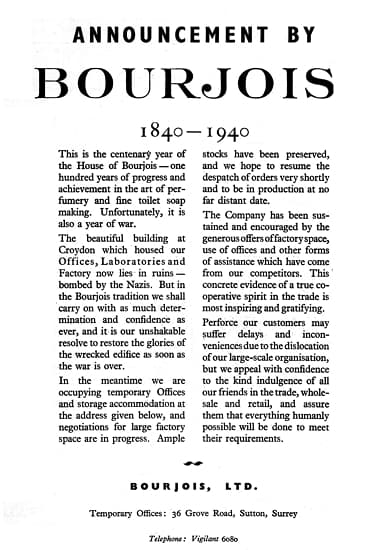

In August, 1940, the Bourjois factory in Britain was bombed during a German raid on Croydon airport and a nearby aircraft factory. Other Bourjois factories in France, Poland, Belgium, and Norway had also been bombed by then or had come under German control.

Above: 1940 Bourjois factory in Croydon after being bombed.

After Croydon was attacked, the British company moved to temporary premises closer into London but this site was also bombed. The company then moved back to Croydon where it was partnered with Pond’s under the 1940 Board of Trade Concentration of Industries Orders. Bourjois’ head office was moved to a temporary address at 36 Grove Road, Sutton in Surrey and remained there even after manufacturing resumed in Croydon in 1943.

Strangely, just after its Croydon factory was bombed in 1940, the British company announced that it was celebrating Bourjois’ Centenary. Publicity material associated with the event claimed that the company had been founded in 1840 when André Bourjois began selling Poudre de Riz de Java from his house. Where they got the date and André Bourjois from is beyond me.

As the German army advanced on Paris in May, 1940, Paul and Pierre Wertheimer drove to Bordeaux with their families in a convoy of cars. From there they took a train across the border to Irun in Spain and then made their way to via Rio de Janeiro to New York. Both bothers became naturalised citizens of the United States in 1941 but Pierre became a Mexican citizen after the war.

To save Bourjois and the other companies owned by Wertheimer Frères from being Aryanised by the Nazis the Wertheimers ‘sold’ their French assets of Bourjois to a friend, Félix Amiot [1894-1974] in October, 1940.

With essential oils from Grasse cut off by the war manufacturing perfumes became more difficult. In 1941, the American company raised its perfume prices but lowered those for its cosmetics. Fortunately, Arnold Louis van Ameringen [1891-1966], the president of Van Ameringen-Haebler, Inc., a major importer of perfume essences, had been stockpiling raw materials from France which allowed Bourjois to continue manufacturing perfumes in the United States including Evening in Paris which remained available there right through the war. Bourjois even managed to introduced a new fragrance called Courage in 1942, the same year it introduced Evening in Paris Creme Parfum.

Above: 1942 Bourjois Evening in Paris Creme Perfume made with a vanishing cream base rather than using alcohol which was needed for the war effort.

The situation in Britain was more critical and Bourjois was forced to stop selling Evening in Paris Perfume in 1943 after supplies of essential concentrates normally sourced from France ran out. It remained unavailable in Britain until May, 1946. Fortunately, many Evening in Paris cosmetics and toiletries were still available right through the war although stocks were subject to quotas laid down by the government. Products available included: Evening in Paris Face Powder, Lipstick, Rouge, Vanishing Cream, Talcum Powder, Toilet Soap, and Shaving Soap.

Post war

In 1945, Pierre Wertheimer traveled from New York to London where he began negotiations with Félix Amiot to restore the Wertheimer interests in Europe. Three years later he became the sole owner of Bourjois. Following the death of his brother in 1948, Pierre bought Paul Wertheimer’s share of the business from his beneficiaries.

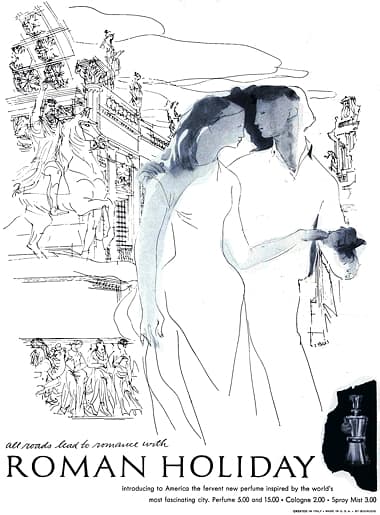

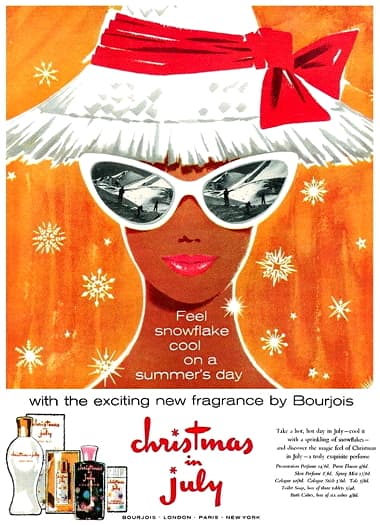

Perfume production resumed in France after VE Day and Soir de Paris became available there once more by 1946 with Mais Oui following in 1947, seven years after it had been introduced in the United States. Thereafter, Bourjois resumed its prewar pattern of releasing new perfumes series on a regular basis. American dates for some of these through to 1960 are: Beau Belle (1949), Endearing (1950), Rampage (1951), Glamour (1954), Christmas in July (1955), Roman Holiday (1955), and Premier Mugent (1957). Some of these perfumes have been attributed to Constantin Weriguine [1899-1982].

Release dates for perfumes differed elsewhere. For example, Endearing did not arrive in Britain until 1952, and Roman Holiday until 1959, the same year Springtime in Paris first went on sale in Britain, seventeen years after it debuted in America and France.

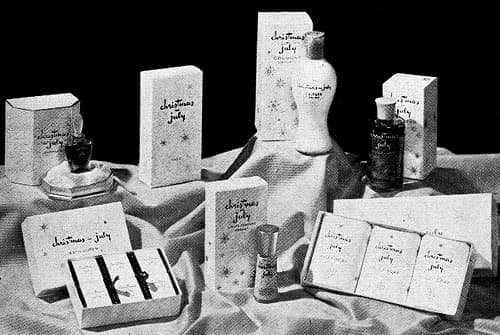

Above: 1960 Christmas in July series (UK). The American version was distributed through Monico, Inc., an affiliate company created by Bourjois in 1955. I do not know why they did this but Monico went on to market other lines such as SiBon bath toiletries and Royale Crest After-Shave.

Sales of Bourjois perfumes in the United States appear to have declined in the immediate postwar period and Richard Lockman [1925-2005], who became the new advertising manager for Bourjois Inc., New York in 1950, introduced a series of publicity stunts throughout 1951 which resulted in the first sales gains in five years.

Above: 1951 One of a series of publicity stunts held in New York to promote Bourjois perfumes. This woman handcuffed to a man was handing out card saying, “There’s an easier way to hold a man—use Bourjois perfume.”

The bottle for Evening in Paris was also redesigned in 1954 and the range was advertised on television, generally around Christmas, which broadcast to every viewer how inexpensive it was. This may have been detrimental in the low run, perhaps ‘cheapening’ the brand and hastening its disappearance in the United States.

Above: 1960 Three Bourjois Christmas advertisements for Evening in Paris, On the Wind, and Little Lady gift sets. The Little Lady range came from Bourjois’ purchase of Helene Pessl in 1960.

See also: Helene Pessl

The cachet of the fragrance was further degraded in America by Bourjois incorporating it into a series of deodorants – Evening in Paris Deodorant Stick containing Neutrasil, a trade name for chlorophyll (1952), Evening in Paris Roll-on Deodorant (1958), and Evening in Paris Cream Deodorant (1961). Unlike most other makers of deodorants and antiperspirants, Bourjois tried to sell its deodorants by their perfume rather than their functionality.

Transition

Bourjois continued to be profitable in the 1950s but there were a number of underlying issues that were proving to be problematic. The company did not have a well developed skin-care range, there had been little in the way of improvements to its make-up range and the usage of its two most popular prewar cosmetics, face powders and rouges, were either in decline or experiencing little or no growth. The idea that women might still buy cosmetics by fragrance was no longer valid. Price was still a factor but so functionality and shade range were on the ascendant.

The archaic nature of Bourjois’ postwar cosmetics can perhaps be demonstrated by the French Soir de Paris beauty routine from 1951.

What a day! And only 10 minutes to “make a beauty” before dinner where you want to shine. Thanks to BOURJOIS you will be the most beautiful and the most admired.

First, soap your face to rid it of all the impurities accumulated during the day. The wonderful BOURJOIS soaps do not irritate the skin: they soften it. They are exquisitely scented.

Since you have delicate skin, now spread a little “Soir de Paris” Cream on your face. Massage gently starting from the chin and the angle of the eye towards the ear. Indispensable base for powder and blushes.

You can’t be beautiful without having your hair done impeccably. To discipline your hair, make it supple and shiny, lightly spray with the luminous “Soir de Paris” brilliantine.

Enhancing the radiance of your complexion, the inimitable pastel shades and the famous “Sour de Paris” powder, fine and “covering”, in your choice of many skilfully studied colours.

Finally, for your lips, a tenacious and brilliant red with the famous “Soir de Paris” red with Biocarmine.

1951 Bourjois advertisement (modified and translated).

There are no specialist skin-creams in this routine and the older vanishing cream/loose powder combination is still being recommended as there is nothing in the Evening in Paris series that could replace it. As far as I can tell, the company did not have a tinted foundation (fond de teint) in its range before 1949.

Looking back from 1950 we can see that there had been little or no development in Bourjois’ skin-care and make-up range for over a decade. As mentioned earlier, new cosmetics were largely clones of older lines scented with a different fragrance. Shade ranges had also stagnated with make-up ranges in 1950 produced in limited shade ranges with most of the available colours being introduced before 1940. For example, French Fards Pastels came thirteen shades in 1950 – Cendre de Roses Pour Brune, Cendre de Roses Pour Blonde, Velouté de Péche, Rose; Corail, Rose Thé, Rose Nacarate, Rose Cyclamen, Rouge Mandarine, Rouge Incarnat, Rose Framboise, and Rouge Mexicain – all dating from 1935 or before.

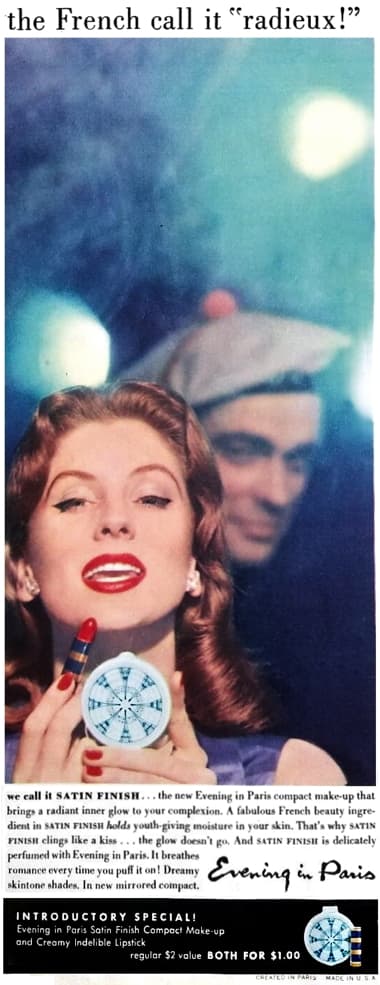

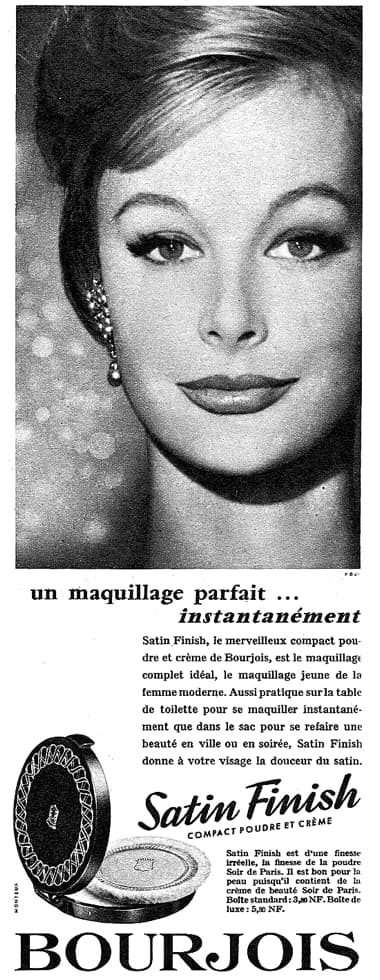

The American company made a move in the right direction when it added Evening in Paris Peaches and Cream Foundation in 1949, Bourjois’ first tinted foundation. This was followed by Evening in Paris Satin Finish in 1950, a long overdue compact powder cream.

Evening in Paris Peaches and Cream Foundation: “A semi-liquid color veil for the skin that doubles the glamour of your face powder. Hides minor surface flaws; plays down tiny surface lines; beneficial as well as beautifying.” Shades: Light, Medium, and Dark.

Evening in Paris Satin Finish Compact: “ [M]ake-up flatters like a powder, clings like a kiss . . . the glow doesn’t go, thanks to a fabulous French beauty ingredient.” Shades: Texas, Miami, Mexico, and Cuba. The Cuba shade was later dropped, presumable due to the Cuban Revolution, and the range became Arizona, Texas, Miami, Florida, and Mexico. By 1962, Bourjois seems to have reverted to descriptive shades such as Rose Beige, Cream Beige, Rachel, Brunette, Fair, and Suntan.

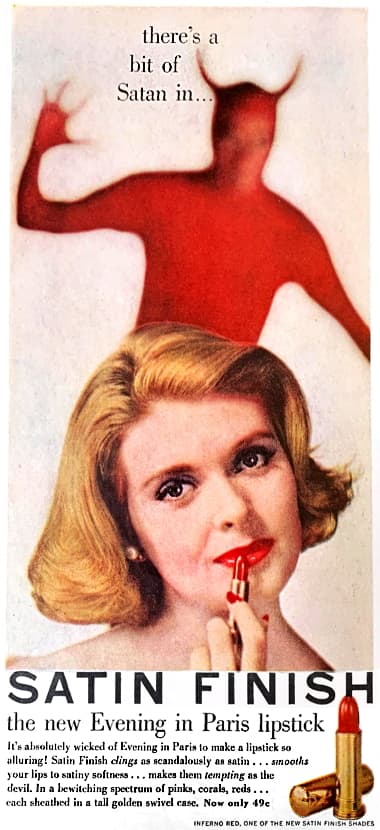

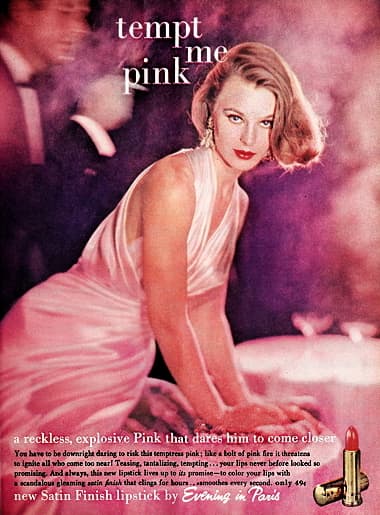

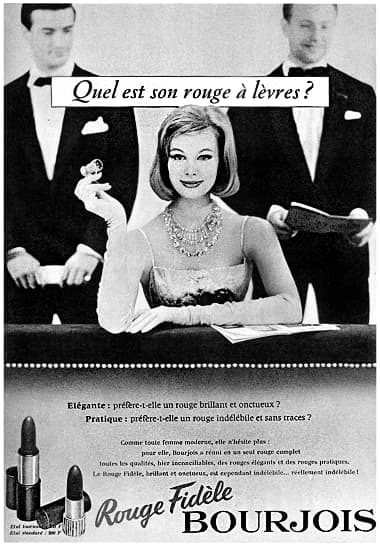

Above: Assorted pre- and post war Evening in Paris Lipsticks.

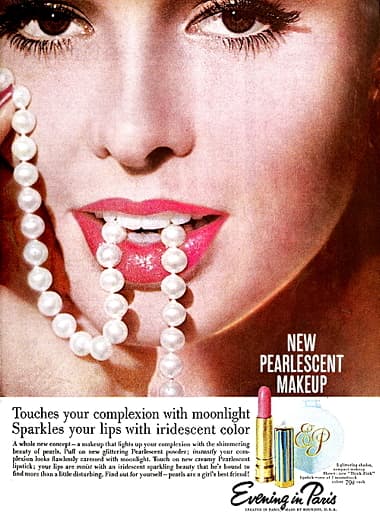

Evening in Paris Satin Finish Lipstick in a gold case was added to the American range in 1958 in six shades – Inferno Red, Tempt Me Pink, Satin Red, Rampage Red, Shimmering Pink, and Spicy Coral. By 1960, Evening in Paris Satin Finish Compact was also available in France along with Satin Beauty Cream Foundation in six shades, and Rouge Fidèle, an indelible lipstick. Notably absent were any developments in skin-care. Bourjois concentrated on make-up with the French company adopting the tag line ‘Le Grand Specialiste du Maquillage’ by 1963. Although fragrances still made up a large part of Bourjois’ revenue for years to come, make-up would eventually become the focus of the company.

Later developments

When Pierre Wertheimer died in 1965, the company passed to his son Jacques Guy Wertheimer [1911-1996] who, from all accounts, did little to advance the Wertheimer interests. His sons, Alain Ernest Wertheimer [b.1948] and Gérald Philippe Wertheimer [b.1951], proved to be better businessmen but appear to be more interested in the upper echelons of the cosmetic and fashion market, selling Bourjois, a budget brand, to Coty in 2015.

Timeline

| 1930 | Wertheimer Frères moves to 43 Avenue Marceau, Paris. International Perfume renamed Bourjois, Inc. Premo plant in Rochester acquired. New Products (UK): Evening in Paris. |

| 1931 | New Products (FRA): Produits de Babette; and Crème Soir de Paris. |

| 1932 | Bourjois Sales Corporation established in New York. New Products (US/FRA): Springtime in Paris/Printemps de Paris. |

| 1933 | New Products (FRA): Biocarmine lipstick. |

| 1934 | A. Bourjois (Britain) moves to Queen’s Way, Croydon. Showrooms opened at 2-5 Old Bond Street. |

| 1935 | New Products (US): Flamme. |

| 1936 | Factory opened in Sydney, Australia. New Products (US/FRA): Kobako. New Products (US): Mansfield for Men. |

| 1938 | New Products (UK): Bon Goût Lipsticks. |

| 1939 | New Products (US): Mais Oui; and Evening in Paris Trio Lotion. |

| 1940 | Croydon factory in Britain bombed. |

| 1942 | New Products (US): Courage; and Evening in Paris Creme Parfum. |

| 1947 | Bourjois (Eastern) Ltd. created in India. New Products (US): Evening in Paris 2-0-8 Face Powder. New Products (FRA): Mais Oui. |

| 1948 | Croydon factory in Britain officially reopened. |

| 1949 | New Products (US): Beau Belle; and Evening in Paris Peaches and Cream Foundation. |

| 1950 | New British soap factory opened at 452 Basingstoke Road, Reading. New Products (US): Endearing; and Evening in Paris Satin Finish Compact. New Products (UK): Mais Oui. |

| 1952 | New Products (US): Evening in Paris Deodorant Stick. New Products (UK): Endearing. |

| 1953 | Bourjois and Barbara Gould combine sales forces in America. |

| 1954 | Evening in Paris bottle redesigned in America. New Products (US): Glamour. |

| 1955 | Monico Inc. founded in New York. New Products (US): Roman Holiday; and Christmas in July. |

| 1956 | New Products (UK): Evening in Paris Satin Finish Compact. |

| 1957 | New Products (US): Premier Mugent. |

| 1958 | New Products (US): Evening in Paris Roll on Deodorant. New Products (UK): Evening in Paris Hand Cream. |

| 1959 | New Products (UK): Springtime in Paris; and Roman Holiday. |

| 1960 | Helene Pessl acquired. New Products (US): Pearlescent Make-up. New Products (UK): Christmas in July. |

| 1961 | New Products (US): Evening in Paris Cream Deodorant. |

| 1969 | Vestric Ltd. appointed distributors in Btitain. |

| 1974 | Alain and Gerard Wertheimer take control of Wertheimer Frères. |

| 2015 | Coty buys Bourjois. |

First Posted: 15th January 2023

Sources

The American perfumer & essential oil review. (1906-1955). New York: Robbins Perfumer Co. [etc.].

The American perfumer and aromatics. (1956-1960). Pontiac, IL. [etc.], Allured Publishing Corporation [etc.].

The chemist and druggist. (1859-) London: Morgan Brothers.

The drug and cosmetic industry. (1932-1997). New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich [etc.].

Vangreveninge, V., & De Feydeau, É. (2013). La beauté à l’accent français: Depuis 1863. Paris: Editions du Chêne, Hachette Livre.

Pierre Jules Wertheimer [1888-1965].

1931 Bourjois reception in New York City refurbished with a cream ceiling, green walls with silver edging and a carpet in two tones of gray-green.

1932 Bourjois Babette Vernis pour les Ongles (Spain).

1933 Babette Eau Rafraichissante, Cleansing Cream, and Skinfood Cream (Spain).

1933 Bourjois Printemps de Paris.

1933 Bourjois Springtime in Paris series including Perfume, Toilet Water, Bath Salts, Talcum Powder, Face Powder, Lipstick, Rouge, and Compact (US).

1933 Bourjois costume rouge and lipstick in Green, Blue Black, Ivory, Gray, and Red cases with a bright chromium trim. The large lipstick had a swivel action and could be refilled, the smaller used a slider (US).

1933 Bourjois Ashes of Roses series (Australia).

1933 Bourjois Biocarmine.

1933 Bourjois Poudre Printemps de Paris.

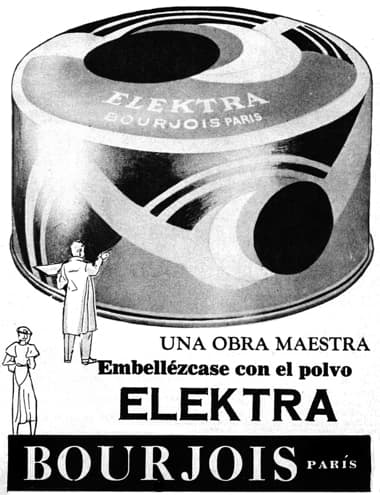

1934 Bourjois Poudre Elektra (Cuba).

1934 Trade advertisement for Bourjois Easter novelties. Bourjois also tried to reduce its reliance on Christmas sales by developing Evening in Paris lines for other events such as Easter.

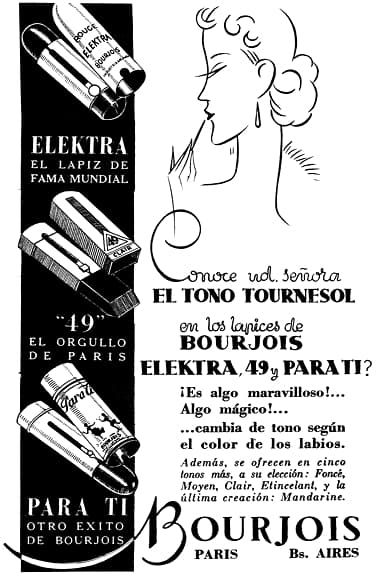

1934 Bourjois Elektra, 49, and Para Ti Lipsticks (Argentina).

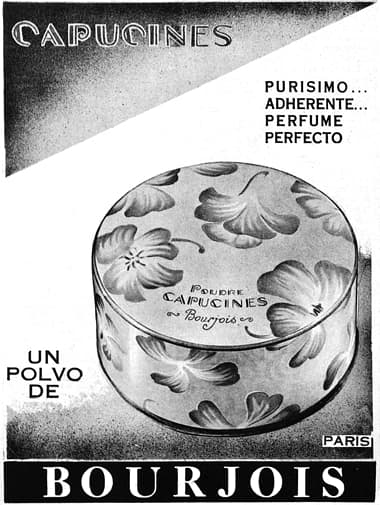

1934 Bourjois Poudre Capucines (Cuba).

1935 Bourjois ‘Back-of-hand-test’ (US).

1935 Bourjois Chicote, perfume del hombre (Spain).

1936 Bourjois Kobako (US).

1936 Bourjois Crème Soir de Paris for the handbag and Poudre Soir de Paris.

1936 Bourjois Fards Pastel (Women would first vote in French elections in 1945).

1936 Bourjois Mansfield for Men (US).

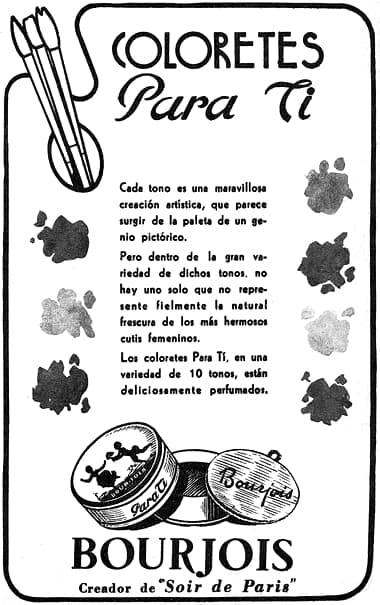

1937 Bourjois Para Ti in 10 shades (Argentina). This may have been South American version of the French Pocket cosmetics.

1938 Trade advertisement for Bon Goût Lipsticks (UK). I can find no reference to a Bourjois lipstick of this name being sold in France.

1938 Bourjois Fards Pastel.

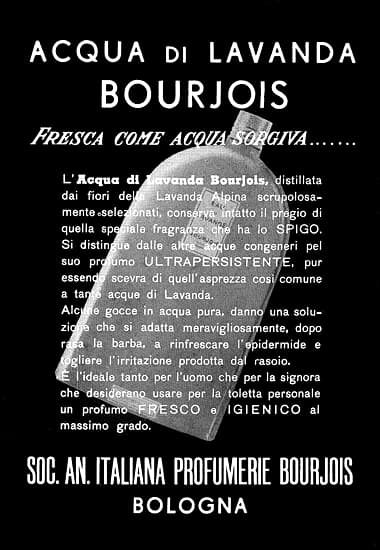

1939 Bourjois Acqua di Lavanda (Italy).

1939 Bourjois Mai Oui (US).

1939 Bourjois Poudre Soir de Paris.

1940 Bourjois’ supposed centenary (UK).

1945 Bourjois Courage.

1947 Bourjois Evening in Paris Lipstick display case made from Plexiglass and aluminium. Shades: Dark, Rose, Medium, Rose Pompon, Currant Rose, and Brilliant (US).

1947 Bourjois Evening in Paris 2-0-8 Face Powder. The clear plastic base allowed customers to view the powder shade (US).

1950 Bourjois Special Beauty Cream, Vanishing Cream and Cleansing Cream (Denmark).

1951 Bourjois Evening in Paris Satin Finish Compact in a gold finish.

1955 Bourjois Evening in Paris Deodorant Stick.

1956 Bourjois Evening in Paris Satin Finish Compact and Creamy Indelible Lipstick (US). Redesigned in 1955, the compact had a white pearlescent plastic case with a lid embossed with metallic-blue Eiffel Towers and stars.

1956 Bourjois Roman Holiday (US).

1956 Bourjois Evening in Paris Satin Finish Compact in Texas, Miami, Mexico, and Cuba shades. Note the use of the traditional Evening in Paris pattern rather than Eiffel Towers (UK).

1957 Bourjois Evening in Paris Inferno Red Satin Finish Lipstick (US).

1958 Bourjois Evening in Paris Tempt Me Pink Satin Finish Lipstick (US).

1959 Bourjois Rouge Fidèle.

1960 Bourjois Christmas in July (UK).

1960 Bourjois Soir de Paris Satin Finish.

1960 Bourjois Pearlescent Make-up in a new powder compact in five shades with lipsticks in a new case in seven ‘moonstruck colors’ (US).