Bourjois

Continued onto: Bourjois (post 1930)

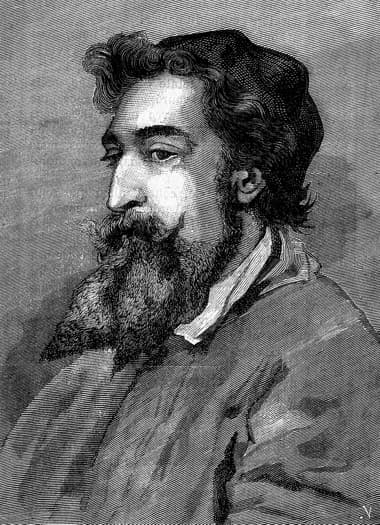

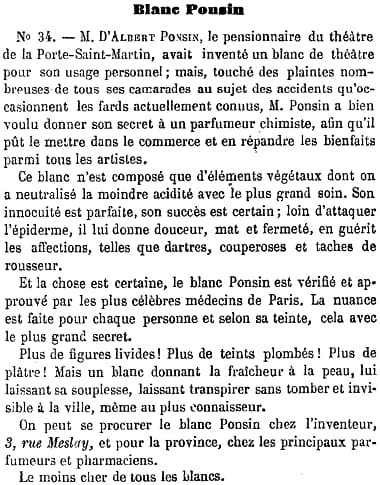

The origins of Bourjois (pronounced Bourge-wah) start with Joseph-Albert Ponsin selling Blanc Ponsin, a theatrical white he had developed while working as an actor. Sales began at 3 Rue Meslay, Paris in 1863 but operations moved to 62 Rue Meslay later in the year.

Blanc Ponsin came in two versions, both packaged in red porcelain pots. A cheaper theatrical form (Blanc Ponsin Pour Le Théatre) was produced in twelve shades including general colours such as Rose, Blanc, and Jaune, as well as shades such as Nègre, Mulâtre, Indien, Cuivré, and Infernal that were used to make up stock theatrical characters of the day.

The more expensive version for general usage (Blanc Ponsin Pour La Ville) came in six shades, including Rose, Rachel, and Blanc. Ponsin’s decision to produce this reflects the increasing use of make-up by sections of Parisian society.

Above: 1868 Parfumerie Théatrale de J -A Ponsin.

I do not know the composition of Blanc Ponsin but it was advertised as harmless so it may have been free of the white lead found in some theatrical make-up used at the time.

Le seul blanc de ville qui soit insisible, le seul blanc de théatre qui ne soit point nuisible.

Translation: The only theatrical white that’s not harmful; it’s the only white in town that’s invisible.(Ponsin advertisement, 1883)

After moving to 62 Rue Meslay, Ponsin opened up additional businesses there in conjunction with a series of investors collectively forming what was known as the Maison de Joseph-Albert Ponsin. One of the investors was a Monsieur Heyer who became a partner of the Parfumerie Théatrale de J. -A. Ponsin in 1866.

By 1868, the first floor of the Maison de Joseph-Albert Ponsin contained a shop that made and sold gloves; the second housed Ponsin and Heyer’s perfume and make-up business; the third a theatrical agency which also sold editions of music and plays along with photographs taken by the agency’s photographer; the fourth the offices of the ‘Théatre Journal’, a newspaper; and the fifth laboratories where perfumes and soaps were made.

Above: 1868 Maison J.-A.Ponsin.

Unfortunately, Ponsin got into financial difficulties and was declared bankrupt in 1868. The cosmetic business was then sold to Alexandre-Napoléon Bourjois [1845-1893], who had been working as its chemist/manager. Bourjois had married Caroline Louise Chanut [1842-1916] earlier in the year and it is generally reported that he used her dowry to buy the business. However, it is equally possible that this was a collective decision by the newly married couple to ensure their continued economic security.

Now known as A. Bourjois, the business remained at 62 Rue Meslay until 1879 when operations were moved to 14 Boulevard Saint-Martin. An address of 15 Rue de Bondy is also listed which, I imagine, was the site of a factory.

When Bourjois bought the Parfumerie Théatrale de J. -A. Ponsin there were about 100 products in its inventory. Of these, the only additional products I have information for are Blanc Gras Pour La Ville and Blanc Gras Pour Le Théatre, two face creams sold in white porcelain pots in three shades: Blanc, Jaune, and Rose.

Above: 1868 Produits Spéciaux de J.-A.Ponsin.

Shortly after Bourjois bought Ponsin’s cosmetic business the Second French Empire came to an end following the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. The Prussian bombardment of Paris and the destruction instigated by the Paris commune of 1871 made Parisian life very difficult for a while.

The Treaty of Frankfurt (1871), which formally ended the Franco-Prussian War, would affect the development of Bourjois at a later date. Under the terms of the treaty the French regions of Alsace and Lorraine were ceded to Germany. This caused Ernest Wertheimer [1852-1927] and his brother Julien Wertheimer [1851-1913] to move from Alsace to France so that they would remain French citizens. They would later play a major role in the fortunes of Bourjois.

The establishment of the French Third Republic in September, 1870, was followed by a period of French history later known as ‘La Belle Époque’, a time when Paris flourished and cemented its place as the fashion capital of the world.

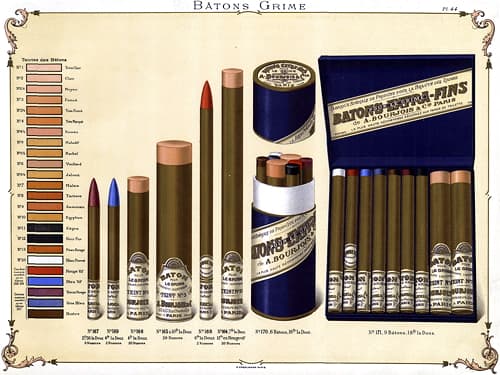

The 1870s also saw a marked divergence between stage and street make-up after Johann Ludwig Leichner [1836-1912] began manufacturing greasepaint in 1873. Greasepaint was better suited to the brighter gas lighting that replaced candles in theatres in the mid-nineteenth century and replaced a lot of the older powder make-up then used on the stage. It became almost essential when electric stage lighting was introduced later in the century.

See also: Greasepaint and Leichner

The Franco-Prussian War had increased French hostility to all things German. This helped create opportunities for French companies such as Dorin and Bourjois to make and sell French greasepaint matching similar products introduced by Leichner. I do not know exactly when Bourjois began making ‘bâtons pour le grime’ and the only information I have on the range comes from a catalogue Bourjois produced in 1898.

Above: 1898 Bourjois Bâtons Grime.

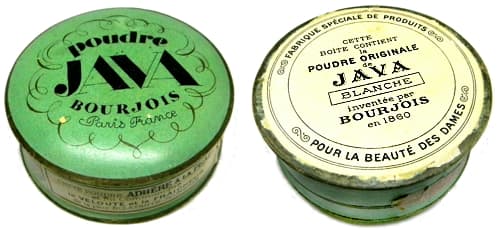

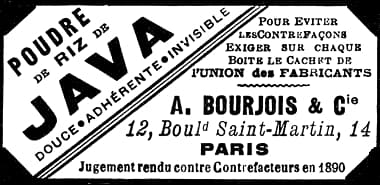

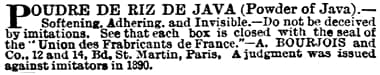

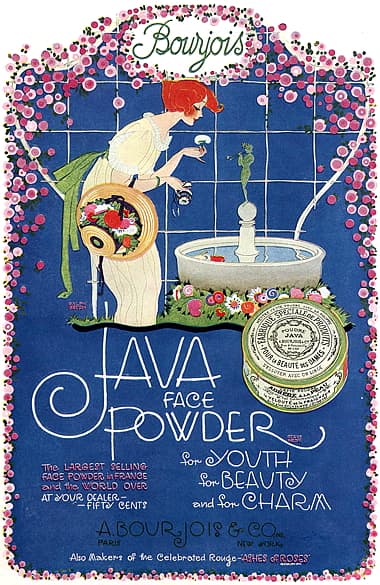

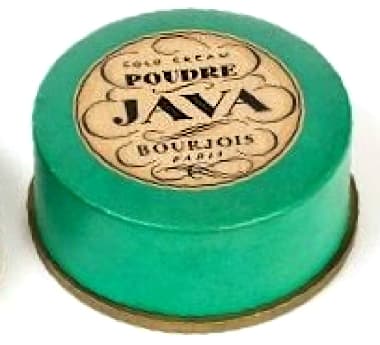

I also have very little information on the introduction of new street make-up (pour la ville) produced by Bourjois between 1868 and 1900. One exception to this was Poudre de Riz de Java which Vangreveninge & De Feydeau (2013) report came in four shades – Blanc, Rose, Naturelle, and Rachel – and date from 1879. This is the earliest validated record I have for it as well but I suggest that it originally only came in three shades – Blanc, Rose, and Rachel.

For completeness, I should point out that I have also seen a powder box which states that it was invented in 1860.

Above: Bourjois Poudre Java.

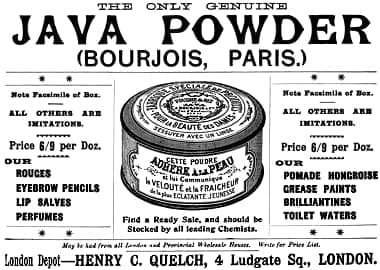

Despite its name, a chemical analysis from the early twentieth century found that Poudre de Riz de Java was composed of 32.6% zinc oxide and 67.4% talc, not rice powder. It was very successful, won awards in London (1908), Brussels (1910), and San Francisco (1914) and became a staple Bourjois cosmetic for decades to come.

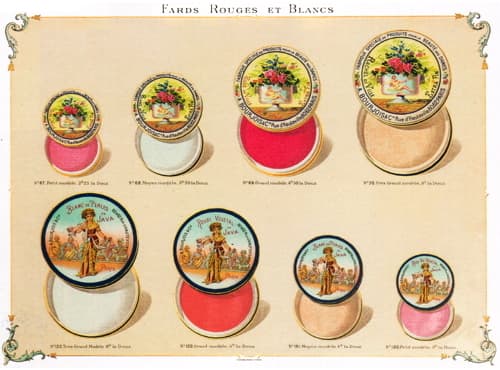

Vangreveninge & De Feydeau (2013) also write that Bourjois began manufacturing rouge pots in 1879 using a method that Bourjois claims to have invented. This involved mixing pigments and powders with water, adding a little perfume, and then moulding the resulting paste into disks which were then dried, polished by hand and glued into containers. The technique was not without some precedence. Pradal & Malepeyre outlined a similar technique to make dried rouge cakes in 1863 but used oil and gum to bind the mixture rather than water.

I don’t have information on the shade ranges of these early rouge pots but the 1898 catalogue lists at least two forms: a more expensive Rose de Ville that was Extra Fin; and a cheaper Rouge Vegetal de Java. However, this catalogue was produced almost two decades after Bourjois was presumed to have first introduced them.

Above: 1898 Bourjois Fards Rouges et Blancs.

The main difference between Rose de Ville and Rouge Vegetal de Java was most likely to have been the red pigment used to colour them. More costly rouges used carmine, an expensive red extracted from insects, while cheaper rouges used less expensive, plant-based (vegetal) reds, such as cathamine.

See also: Rouge

Partnership

By 1890, Bourjois was exporting its products across parts of Europe and Poudre de Riz de Java was becoming so successful that the company had to take legal action against imitators.

To help the business grow, Bourjois partnered with Émile Orosdi [1869-1918] in 1890 and together they founded A. Bourjois et Cie (capital ₣250,000). Ordosi’s extended family owned a number of department stores in Europe which would have been used to sell Bourjois products and their collective marketing experience must also have been helpful.

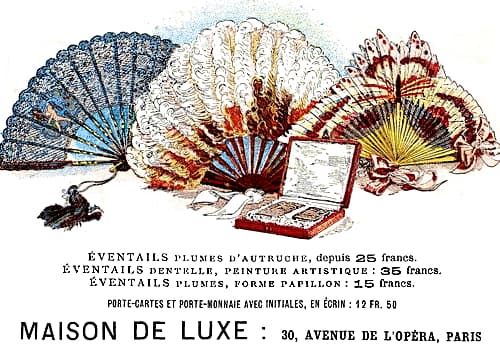

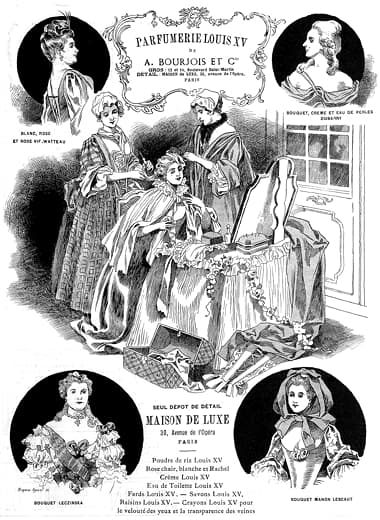

The Bourjois establishment on the Boulevard Saint-Martin continued to act as a wholesaler but the company now began retailing its products through the Maison de Luxe, an upmarket store that sold a variety of goods but was best known for its ostrich feather fans.

Above: 1890 Maison de Luxe at 30 Avenue de L’Opera, Paris.

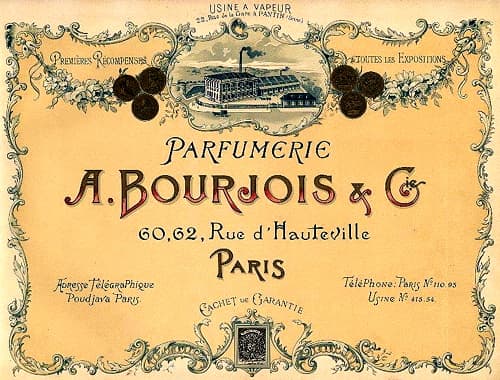

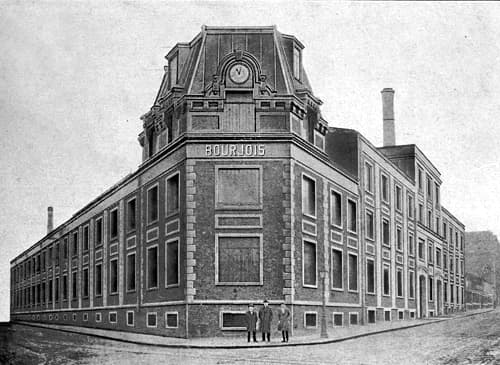

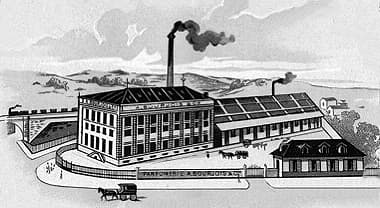

In 1891, Bourgois increased its capitalisation to ₣300,000, using the funds to establish a new factory at 22 Rue de La Gare, Pantin. The site was next to a rail line and near the Canal de l’Ourcq so had good access to transportation. It was also close to the slaughterhouses of La Villette built by Baron Haussmann [1809-1891] during the renovation of Paris. Slaughterhouses were a good source for the fat and tallow then used in many cosmetics.

Above: 1898 Bourjois et Cie with a steam-powered factory based 22 Rue de la Gare, Pantin.

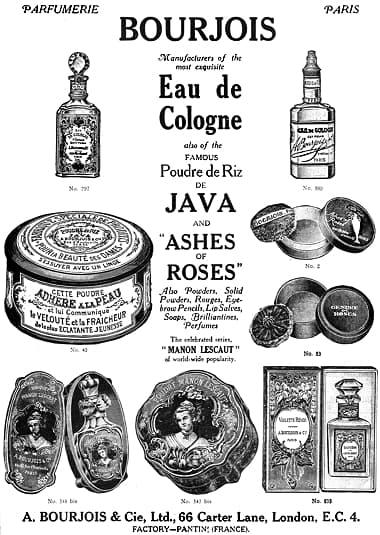

In 1891, A. Bourjois et Cie released the Louis XV range which looked nostalgically back to a highpoint of French art and culture. The line included three fragrances – Leczinska, Du Barry and Manon Lescaut, all women, real or imaginary, from the time of Louis XV, along with Eau de Toilette Louis XV. Cosmetics in the range included: Poudre de Riz Louis XV in Rose Chair, Blanche, and Rachel shades; Crème Du Barry in Blanc Watteau, Rose Watteau, and Rose Vif Watteau shades, a reference to Jean-Antoine Watteau, a French painter from the time of Louis XV; Eau de Perles de Madame Du Barry; Crème Louis XV, probably a cold cream used as a cleanser; Raisins Louis XV, lipsticks in unknown shades; Crayons Louis XV, for the eyes; Crayons Bleus, for drawing blue veins on the skin to make it look more transparent; and Savons Louis XV, soaps.

E. Wertheimer & Cie

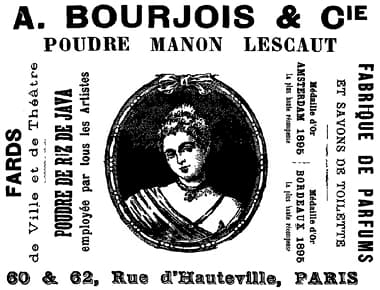

Of Bourjois’ six children, only Albert Bourjois [1886-1968], then aged about seven, was still alive when his father died in 1893. Bourjois’ son-in-law, Charles Rousseau, who had married Marie Louis Bourjois [1873-1892] in 1890, also died in 1894 which meant that there was no-one suitable to carry on the business. Bourjois’ wife, Caroline, decided to sell and Orosdi became the sole proprietor of the business in 1894. Following the sale, Orosdi opened a retail outlet for Bourjois at 13 Rue de la Paix in 1895 and then moved the wholesale business and offices to 60-62 Rue d’Hauteville in 1896.

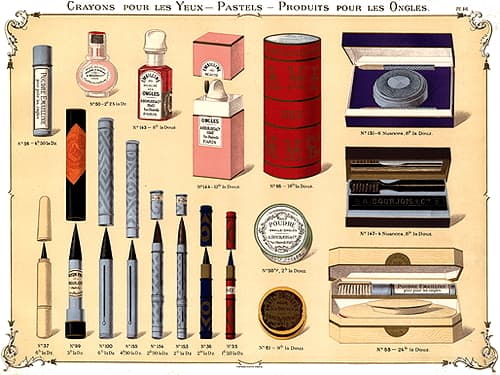

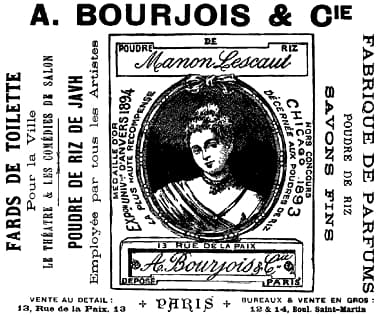

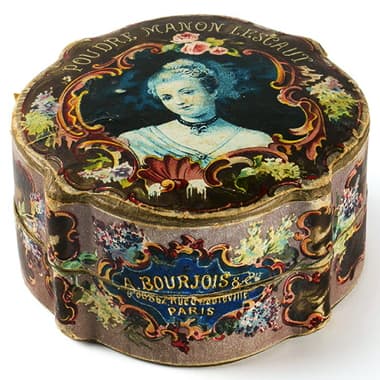

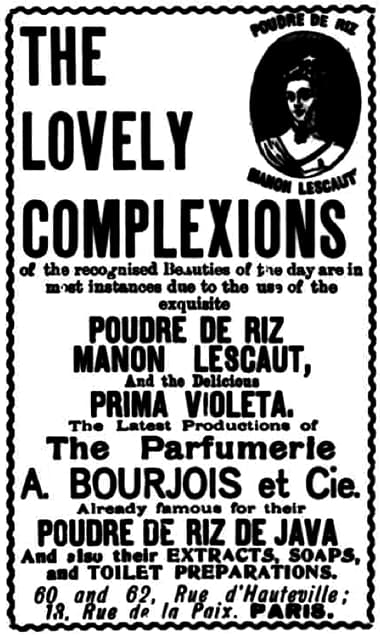

In 1894, Bourjois began advertising Poudre de Riz Manon Lescaut, presumably using the fragrance it had created for the Louis XV range in 1891. The new face powder joined the over 700 items listed in the catalogue Bourjois issued in 1898. This included Bourjois’ extensive fragrance range as well as skin creams, make-up, hair products, dentrifices, nail cosmetics, and soaps. Bourjois has a copy of this in their historical collection but unfortunately very little of it has been published.

Above: 1898 Bourjois Crayons pour les Yeux, Pastels, and Produits pour les Ongles.

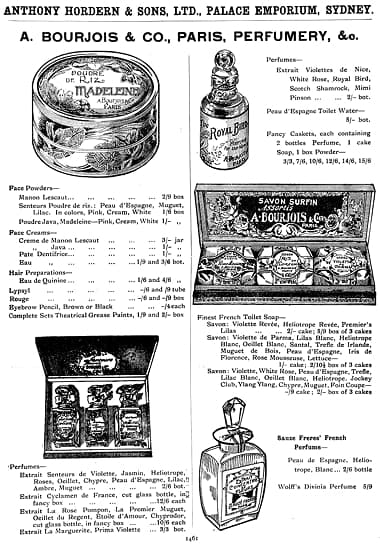

By the time it was produced, many of the products listed in the 1898 catalogue were already being exported around the world. Bourjois products were found as far away as New Zealand by 1894.

Above: c.1890s Perhaps inspired by the fans from the Maison de Luxe, this poster depicts a fan containing images of women from four different historical periods applying perfume or make-up. The woman on the right is about to use Poudre de Riz de Java. Other products mention in the ribbon below the fan are Parfumerie Louis XV, Fards de Toilette, and Essences fines pour le mouchoir.

Wertheimer Frères

In 1898, after coming to an agreement with Orosdi, the previously mentioned Ernest Wertheimer invested ₣250,000 in Bourjois. He also took over the management of the business through his company E. Wertheimer & Cie. Orosdi continued to partner with Wertheimer and the pair invested ₣800,000 in the Parisian department store Galeries Lafayette which allowed Théophile Bader [1864-1942] to dramatically increase its size and scope. It also ensured that Bourjois products were stocked there.

Like Wertheimer, Bader was also from Alsace and he was the person that introduced Wertheimer to Gabrielle Bonheur ‘Coco’ Chanel [1883-1971]. The meeting resulted in the creation of Parfums Chanel in 1924, with Wertheimer holding a 70% stake in the company.

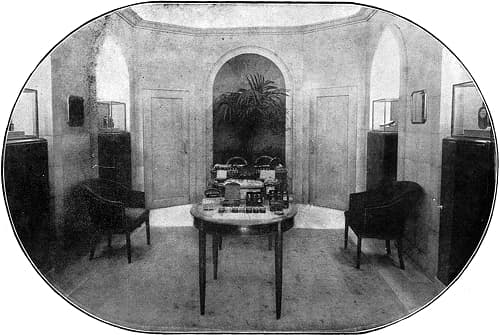

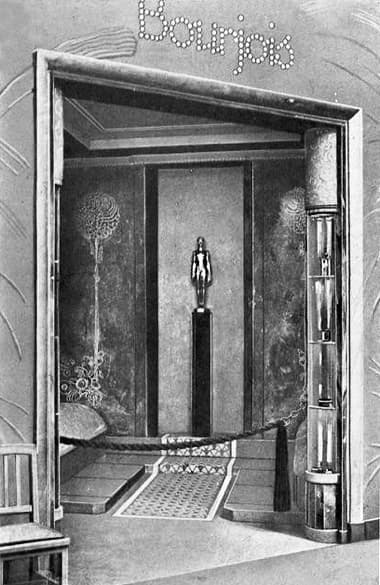

By the time Orosdi died in 1918, Ernest Wertheimer had introduced his two sons, Paul Lehmann Wertheimer [1883-1948] and Pierre Jules Wertheimer [1888-1965] into the business with E. Wertheimer & Cie becoming E. Wertheimer et Fils in 1921. The two brothers took over the management of Bourjois from their father through the Société Wertheimer Frères (capital ₣500,000) founded in 1923 with each brother contributing half of the capital. The management change came with a new retail outlet opened for Bourjois at 28 Place Vendôme in 1923, up the road from their previous shop in the Rue de la Paix.

Above: 1925 Interior of 28 Place Vendôme, Paris.

By then, the factory in Pantin had grown to cover most of the triangular block on which it had been established.

Above: Aerial view Bourjois factory in Pantin.

The main entrance to the factory was now on the Rue Delizy side of the block so the company address was listed as 40 Rue Delizy, rather than the previous 22 Rue de La Gare.

Above: 1925 Bourjois factory in Pantin.

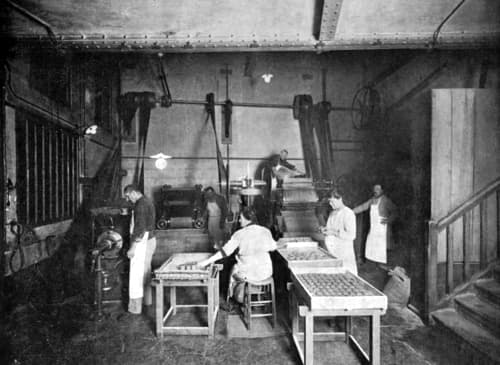

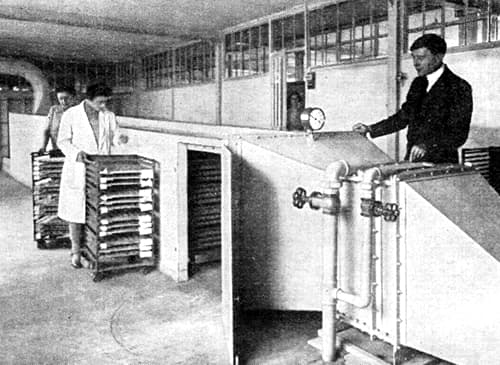

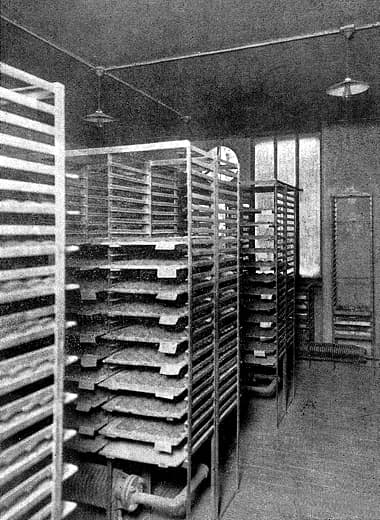

There are a number of photographs of the activities within the factory at Pantin which are typical of cosmetic and perfumery enterprises of the time.

Above: 1925 Mixing powders at the Bourjois factory in Pantin.

Above: 1925 Making soap at the Bourjois factory in Pantin.

Above: 1927 Drying cabinet used in producing rouges at the Bourjois factory in Pantin.

Bourjois was still making theatrical make-up in the 1920s but the its fortunes were now firmly tied to the growing demand for the company’s fragrances, cosmetics, soaps, and toiletries with perfumes, face powders and rouges being the most commonly advertised lines. This emphasis on female beautification was demonstrated by the company’s stand at the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs held in Paris in 1925. It was fitted out as temple of beauty, its focal point a gold statuette of a naked woman standing on a column.

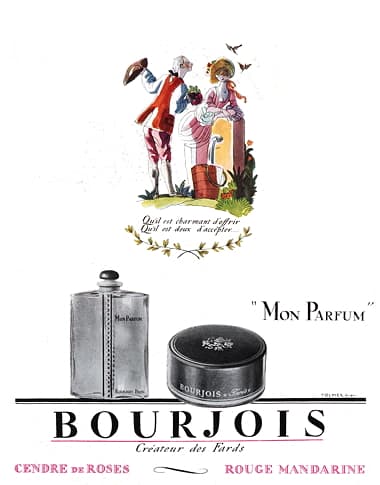

Mon Parfum

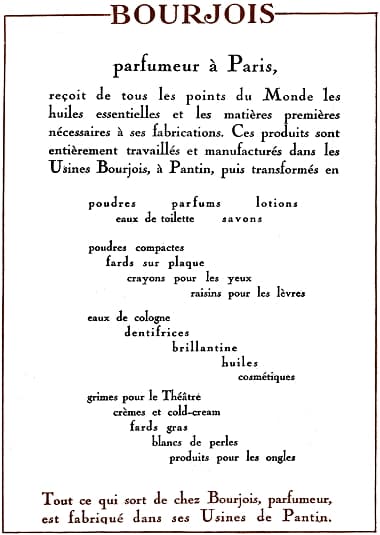

In 1922, Bourjois introduced a new perfume called Mon Parfum, the same year that Chanel [1883-1971] began selling Chanel No. 5 in her shop. Like Chanel No. 5, Mon Parfum was created by Ernest Beaux. It joined a number of other perfumes in the Bourjois inventory such as Marguerite Carré, Chyprodor, Talis, Pergola, Gloriosa, Étoile d’Amour, La Dubarry, Cyclamen de France, Oellet du Regent, Lilas, Iris, Premier Muguet, Quintessence Violette, Ambrodor, Jasmin, and Rose Pompon. These fragrances were also incorporated into lotions, eau de toilettes, powders, soaps, and brilliantines.

Above: 1921 Bourjois Poudres, Fards, Parfums.

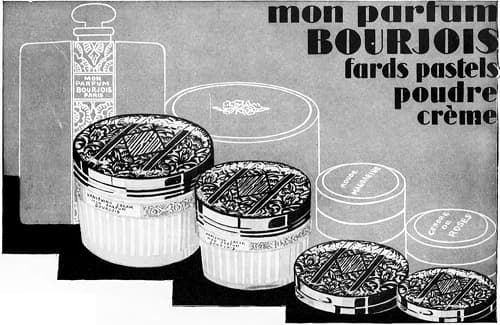

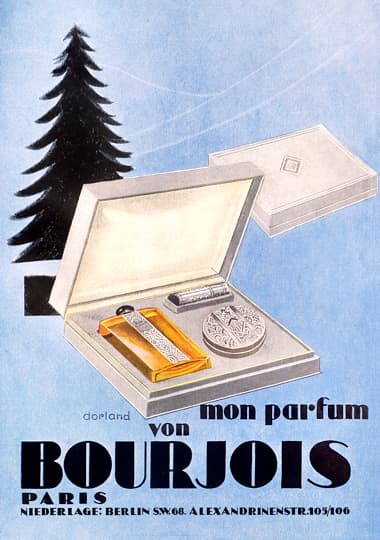

Like previous Bourjois fragrances, Mon Parfum was incorporated into other lines to form a series. The initial lines included Eau de Toilette Mon Parfum; Lotion Mon Parfum; Savon Mon Parfum; Poudre de Riz Mon Parfum, in Blanc, Rose, Chair, Rachel, and Ocre shades; and Talc Mon Parfum.

Poudre de Riz Mon Parfum came in a leatherette case, an idea that was also used to repackage Cendre de Roses and Rouge Mandarine, Bourjois most popular rouges. Poudre de Riz Mon Parfum continued to be sold by Bourjois in the 1930s and its colour range was extended to include Blanche, Rose I, Rose II, P&eacirc;he, Naturelle, Rachel Foncé, Rachel, Ocrée Chair I, Ocrée Chair II, Ocrée !, Ocrée II, Ocre Foncé, and Ocre Soleil shades.

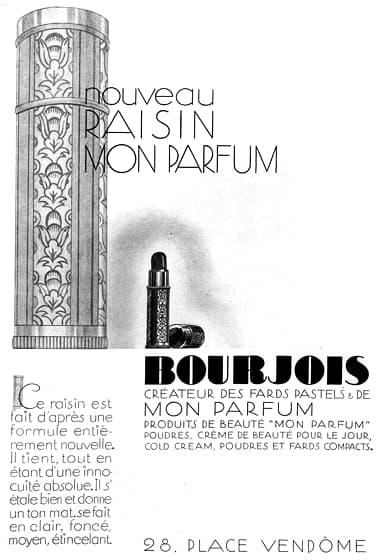

In 1928, Bourjois added Crème de Toilette Mon Parfum, a vanishing cream; Poudre Compacte Mon Parfum and Fard Compact Mon Parfume, powder and rouge compacts; and Raisin Mon Parfum, a lipstick in Clair, Fonce, Moyen, and Étincelant shades. These new items in the Mon Parfum series were packaged in glass containers with silvered lids or silvered compacts, all embossed with a new Bourjois logo.

Above: 1928 Bourjois Mon Parfum Crème de Toilette (Vanishing Cream), Poudre Compacte and Fard Compact.

Bourjois had already added Cold Cream au Citron in 1927 and the use of the terms ‘cold cream’ and ‘vanishing cream’ may be indications of the growing influence of American brands in the French cosmetic market.

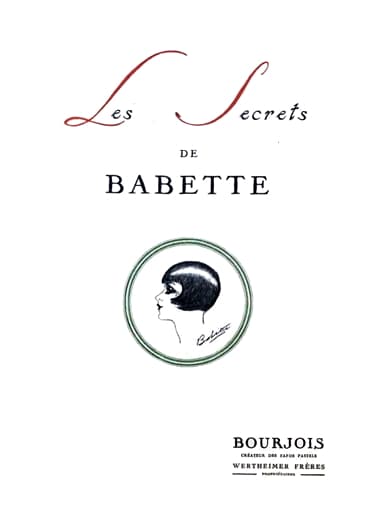

Babette

In 1924, the year following the founding of Wertheimer Frères, Bourjois began a promotional campaign targeting younger women who were more likely to spend money on perfumes and cosmetics. It was based around the activities of Babette, a fictional character who acted as Bourjois’ symbol of the post-war, independent woman. However, Babette’s independence had limits. She dressed fashionably, wore make-up, had bobbed hair, travelled to fashionable places, drove cars, and engaged in sports but never appeared in the more extreme masculine fashions typical of ‘La Garçonne’ and was married not single.

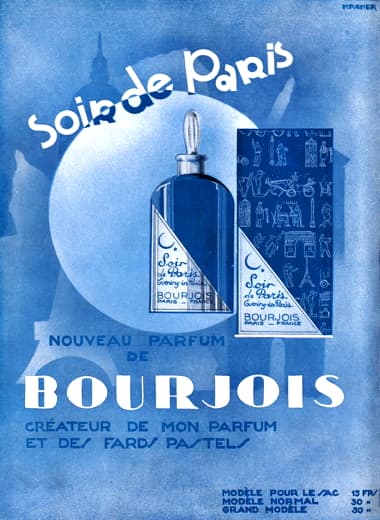

According to Stamelman (2006), the Babette stories were created by the French journalist and writer Germaine Beaumont. Bourjois used advertisements containing her stories about Babette to promote Mon Parfum and Fards Pastel, with the company replacing its tagline ‘Créateur des Fards’ with ‘Créateur des Fards Pastels’ in 1925. Babette would later be used to promote Soir de Paris after it was introduced in France in 1929.

Fards pastel

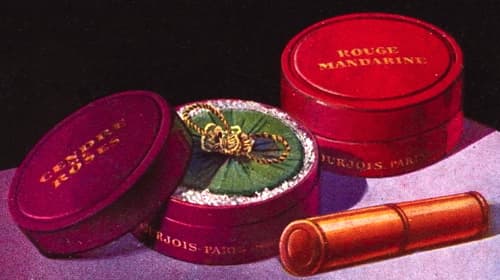

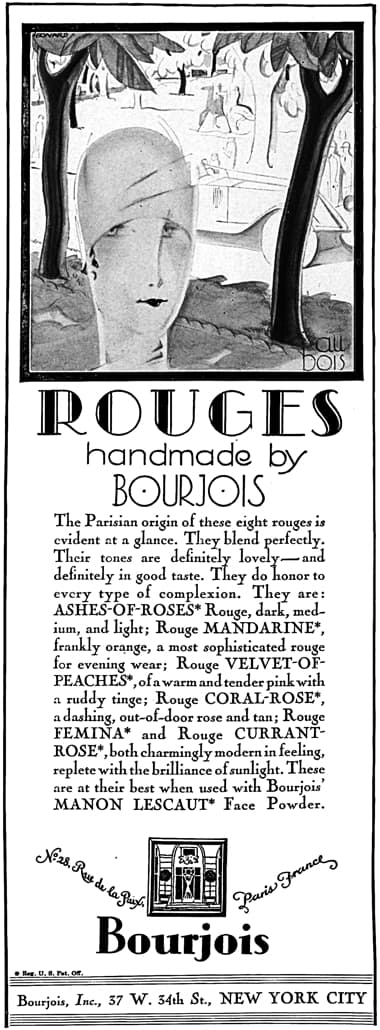

The Fards Pastel were a range of rouges that included the best selling Cendre de Roses, and Rouge Mandarine.

Above: 1925 Bourjois Fards Pastels.

In 1925, there were sixteen Fards Pastel: Cendre de Roses pour Brunes, Cendre de Roses pour Blondes, Rouge Mandarine, Blanche Rose, Naturelle, Rouge, Rachel, Rachel Foncé, Ocre Yedda, Vert Ophélia, Cendra de Santal, Cendra de Violette, Ocre Radja, Velouté de Peche, Rouge Groseille, and Rose Corail. Not all of these were reds or red-browns. For example, Cendre de Violette (violet) and Vert Ophélia (green) could be used to tone down colours to produce a more natural-looking appearance under different lighting conditions.

Not all of these shades survived and others were added later including: Rouge Abricot, Rouge Mexicain, Rose Cyclamen, Rose Thé, Rose Nacarat, Rouge Incarnate, and Rouge Femina. In 1928, Bourjois made some of these rouges available as Compact Pastels in Cendre de Roses pour Brunes, Cendre de Roses pour Blondes, Rouge Mandarine, Rose, Naturelle, Rachel, Rachel Foncé, Ocre Yedda, Cendra de Santal, Ocre Radjah, Velouté Péche, Rouge Groseille, Rose Corail, and Rouge Incarnat shades.

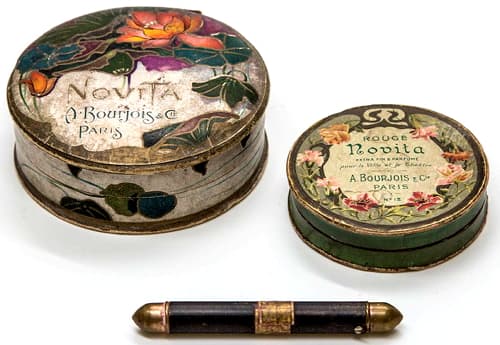

Naturally, rouge was used with other cosmetics such as face powder, lipstick and eye make-up. The main powders sold by Bourjois continued to be Poudre de Riz de Java and Manon Lescaut with lipsticks that included Raisin Elektra, Raisin Pocket, and Raisin Novita all packaged in push-up containers.

Above: Novita Face Powder, Rouge and Lipstick.

Britain

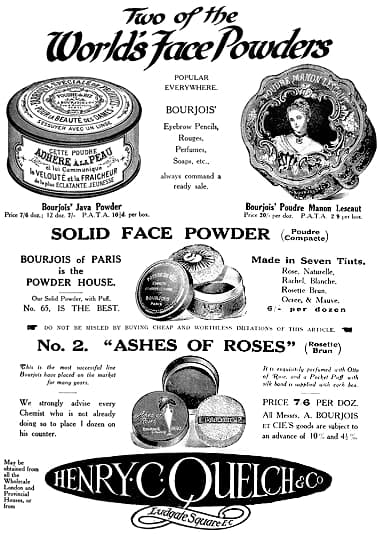

Bourjois was available in Britain by 1892 through their agent May, Roberts and Company. In 1898, the agency was transferred to Henry C. Quelch, a company owned by Henry Charles Quelch [1851-1937] that was based at 4-5 Ludgate Square, London. In 1919, A. Bourgois et Cie Ltd. was founded at 66 Carter Lane, London (capital £15,000) but moved to 4 Water Lane, London in 1924. The directors of the company were Ernest, Paul, and Pierre Wertheimer but the business was managed by Henry Quelch and the Bourjois showrooms remained at Ludgate Square. Henry C. Quelch had also been the agents for Bourjois in the British Dominions, except for Canada, and A. Bourgois et Cie Ltd. now took over this role as well.

Above: 1925 Bourjois showroom in London.

I do know exactly when Bourjois began manufacturing in Britain but note that A. F. Bayford & Co. Ltd. (capital £10,000) was founded at 4-5 Ludgate Square in 1924 to manufacture a range of manicure products, toiletries, cosmetics and perfumes. In 1926, A. Bourjois et Cie Ltd. also announced that they were moving manufacturing from 4-5 Ludgate Square to a new factory at 71-72 Carter Lane. This suggests that some local manufacturing of Bourjois products may have taken place as early as 1924 even though the British company gives the date it first began local manufacturing as 1926. Soap manufacturing in Britain commenced in 1927.

Bourjois cosmetics had been available in British Dominions in the 1890s but the first overseas company was not created there until 1922 when A. Bourjois et Cie (Australasia) Ltd. (capital AUS£50,000) was established at MacDonell House, 315 Pitt Street, Sydney. It moved to Broughton House at 177-179 Clarence Street, Sydney in 1926 and opened a branch in Wellington, New Zealand in 1925. By 1927, Bourjois was being distributed across the British Dominions in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Egypt, India, Ceylon, British West Indies, Gibraltar, and Malta.

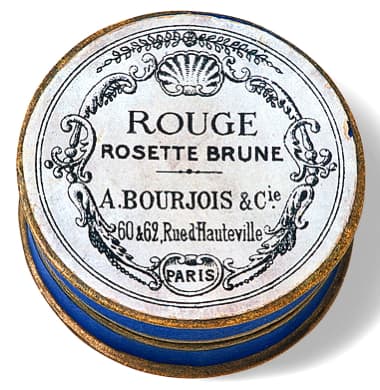

Above: Restaurant Frascati (London) fan scented with Mon Parfum.

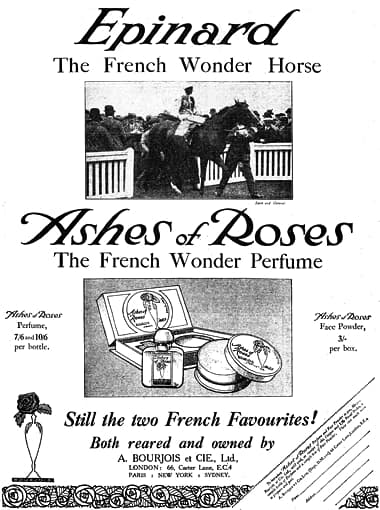

The Ashes of Roses series was the most popular Bourjois cosmetic range in Britain and the British dominions in the 1920s. The first item in the series was a compact rouge in Rosette Brune shade sold in a circular cardboard case perfumed with Otto of Roses. Ashes of Roses translates as Cendre de Roses in French but the two items were different. The Rosette Brune shade of Ashes of Roses Rouge also did not replace the original Rosette Brune Rouge which continued to be sold in its familiar striped cardboard container. The same can be also said of the Mandarine shade when that was added to the Ashes of Roses series, Bourjois continued to sell Rouge Mandarine separately in a leatherette box.

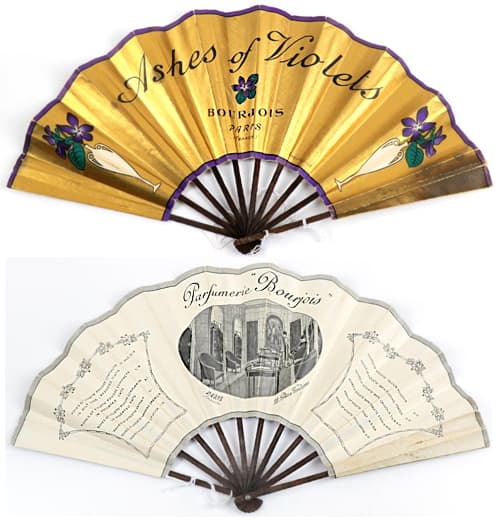

Above: Bourjois Ashes of Roses Fan.

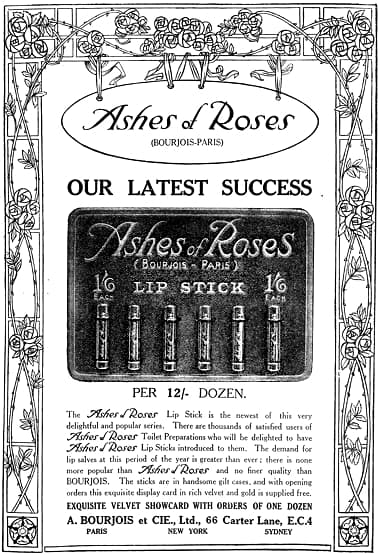

By 1923, the British Ashes of Roses series included Ashes of Roses Face Powder, Bath Powder, Bath Crystals, and Talcum Powder. Later lines included: Ashes of Roses Lip Stick in a gilt, push-up case, Soap, Vanishing Cream, and Eau de Cologne (1923); Ashes of Roses Cold Cream, and Baby Powder (1924); Ashes of Roses Depilatory (1925); Ashes of Roses Crystallised Brilliantine, and Liquid Brilliantine (1927); and Ashes of Roses Night Cream (1928). Shade names tended to follow those used in France.

Ashes of Roses Face Powder (loose and compact): “A triumph of French art. Unrivalled for smoothness of texture and invisibility, delightfully perfumed. Like a bloom gathered from the rose.” Shades: Naturelle, Rachel, Blanche, Rose, and Brunette.

Ashes of Roses Cold Cream: “[T]he true skin food—it creates that bloom of health and a soft, rounded suppleness.”

Ashes of Roses Vanishing Cream: “An exquisite cream of lasting freshness and delightful perfume—a perfect base for powder.”

Ashes of Roses Night Cream: “Softens and nourishes the skin and removes all impurities from the pores while you sleep.”

Ashes of Roses Lip Stick: “[A]dds that last alluring touch to beauty.” Shades: Light, and Dark.

Ashes of Roses Depilatory: “[R]emoves superfluous hair in a few minutes, quickly, safely and surely, leaving the skin smooth and soft and in no way irritated.”

Above: 1927 Window display for Ashes of Roses in Rochdale, England.

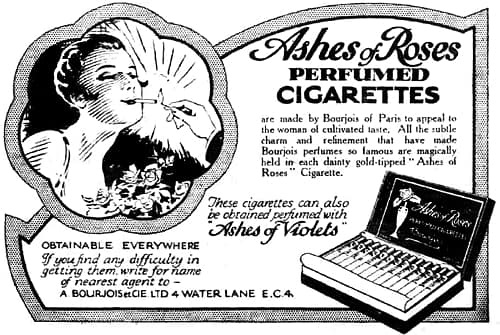

In 1927, Bourjois also came to an agreement with the Silver Perfumes Cigarette Company who then began to sell Ashes of Roses scented cigarettes.

Above: 1927 Ashes of Roses Perfumed Cigarettes.

See also: L’art de la Toilette (c.1929)

In 1925, Bourjois added an Ashes of Violets series – Face Powder, Compact Powder, Talcum Powder, Vanishing Cream, Lip Stick, Liquid Brilliantine, Solid Brilliantine, Soap, and Bath Crystals – in violet and gold packaging with an Ashes of Carnations series in green and gold packaging added in 1929.

Above: Bourjois Ashes of Violets Fan.

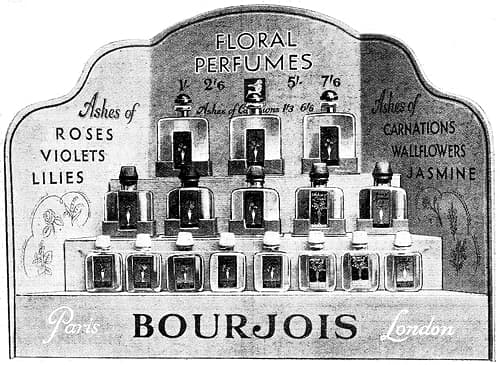

Bourjois also sold Ashes of Lilies, Ashes of Wallflowers and Ashes of Jasmine floral perfumes in Britain but I have no evidence that these were also turned into a series.

Above: 1931 Bourjois Floral Perfumes display stand (UK).

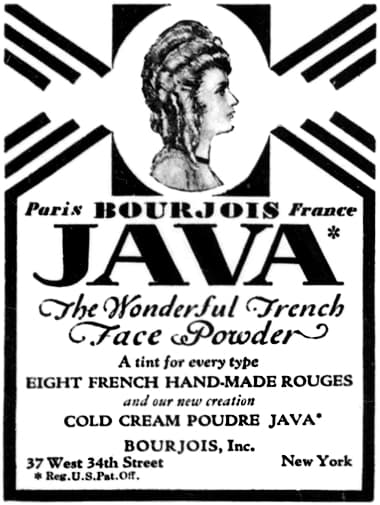

United States

Bourjois was available in the Americas by the 1880s with an American company, A. Bourjois & Co. Inc. (capital US$10,000) established at 25 Broad Street, New York in 1913, selling its products through agents. The company moved to the Oppenheim-Collins Building at 35 West 34th Street, New York in 1916 and began selling direct to customers across the United States the following year. Some product packaging was taking place in America by 1920 and local manufacturing began in earnest in 1923.

Above: 1925 Bourjois showroom in New York.

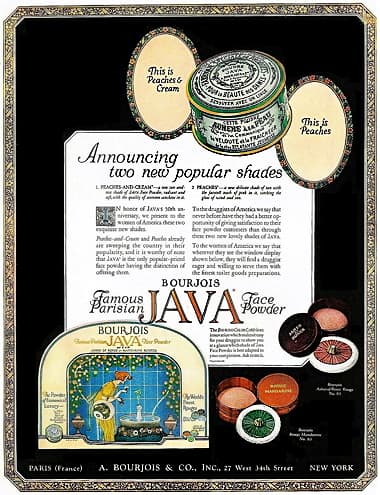

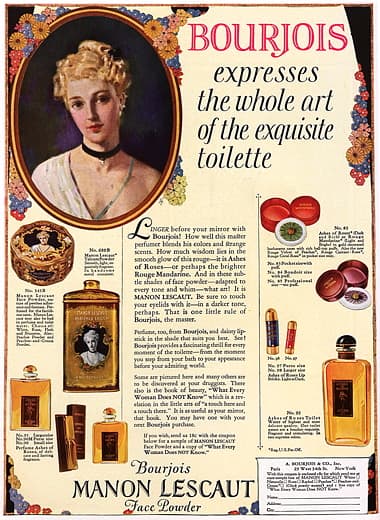

Both Java Face Powder and Manon Lescaut Face Powder featured in American advertisements in the 1920s but they were aimed at different sectors of the American market. Java Face Powder was cheaper and advertised to appeal to more conservative women, while the more expensive Manon Lescaut was aimed at younger more adventurous women often referred to as ‘flappers’ in 1920s America. In France, these women were represented by Babette but she was not used in British or American advertising.

Java Face Powder: “[U]sed by more women than any other face powder in the world. … [N]o face powder could be made better or purer; none succeeds better in keeping the complexion fair and fragrant.” Shades: White, Rose, Naturelle, and Rachel, with Peaches and Cream, and Peaches added in 1923.

Manon Lescaut Face Powder: “Its use will add to your personal charm a distinctiveness for which every woman strives.” Shades: White, Rose, Naturelle, Rachel, and Peaches and Cream. Later shades were Peaches (1923), Mauve (1926), and Ocrée (1927).

For some unknown reason, the Manon Lescaut Peaches, and Peaches and Cream Face Powders were packaged differently to others in the Manon Lescaut range although they used the same box shape.

In 1926, Bourjois also introduced a Cold Cream Poudre Java. It may have been produced specifically for the American market to compete with other cold cream face powders such as Armand Cold Cream Powder which was very successful in the 1920s.

Also see: Armand

An Ashes of Roses series was available in the United States but it does not seem to have been as extensive as the one that was popular in Britain and the British Dominions. The only products I have been able to identify in the American series were Ashes of Roses Perfume, Toilet Water, Face Powder, Vanishing Cream, Rouge, Lipstick, Talcum Powder, Bath Salts, and Soap.

Unlike the British Ashes of Roses Rouge, the American version seems to have been identical to the French Cendre de Roses and was sold in the same leatherette box. Rouge Mandarine was also available in the United States with Rouge Currant-Rose, Rouge Coral Rose, and Rouge Velvet-of-Peaches available by 1924, and Rouge Femina in 1925. I assume these are the American equivalents of the French Rouge Mandarine, Rose Groseille, Rose Corail, Velouté de Péche, and Rouge Femina.

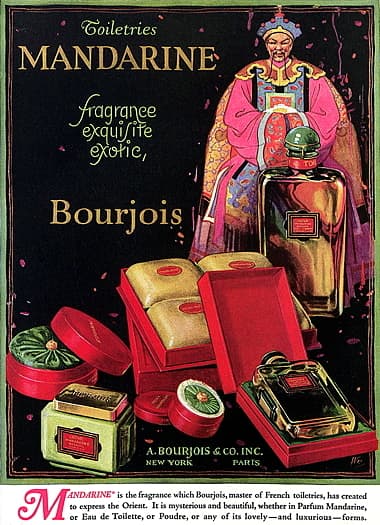

By 1924, a Mandarine series was also available in the United States containing Mandarine Toilet Water, Savon Mandarine, Creme Mandarine, Poudre Mandarine in White, Naturelle, and Rachel shades, Rouge Mandarine, and Mandarine Lipstick. Some of these were taken from other ranges. For example, Poudre Mandarine was actually the Mandarine shade of Ashes of Roses Face Powder.

Merger

By the end of the 1920s, the United States had become the largest cosmetic market in the world and Pierre Wertheimer was making annual trips to America to consult with the directors of the American firm.

To help strengthen its position in America, Bourjois combined forces with Woodworth, an American perfume and cosmetics company established in 1856 that had an extensive distribution network in drug stores across the United States. In February, 1929, Bourjois and Woodworth were merged into a new company, the International Perfume Company, Inc., but after the Wall Street crash of November, 1929 its name was changed to Bourjois, Inc. (New York).

The amalgamation with Woodworth included Barbara Gould Ltd., which produced a cosmetic range Woodworth had started in 1928. Rather than disband Barbara Gould, Bourjois extended its product range and also introduced the line into France, Europe, and Britain in the 1930s.

See also: Barbara Gould

Evening in Paris

In June, 1928, Bourjois began sponsoring a weekly one-hour radio program called ‘Evening in Paris’ and then released Evening in Paris Parfum into the American market in November. Like Mon Parfum, the perfume was formulated by Ernest Beaux. It was packaged in a distinctive sapphire-blue bottle designed by Jean Helleu [1894-1985], a relative by marriage of Émile Orosdi, the previous owner of Bourjois, and was labelled and boxed in blue and silver, colours that were said to be inspired by the horse-racing silks of Pierre Wertheimer.

The perfume and the series developed from it proved to be very popular. The perfume’s success can perhaps be put down to three things, its formulation, the backing of a radio program, and the fact that it was cheaper than many other fully imported French perfumes. Producing the perfume in a wide range of sizes with differing price points was also helpful, particularly so during the Great Depression.

Following its success in the United States, Evening in Paris was introduced into France as Soir de Paris in 1929 and then into Britain in 1930 with radio used to promote the range in both cases.

Timeline

| 1868 | Alexandre-Napoléon Bourjois buys the Parfumerie Théatrale de J. -A. Ponsin. |

| 1879 | Business moved to 14 Boulevard Saint-Martin. New Products (FRA): Poudre de Riz de Java. |

| 1890 | A. Bourjois et Cie founded at 12-14 Boulevard Saint-Martin, Paris. |

| 1891 | Factory established at 22 Rue de la Gare, Pantin. New Products (FRA): Louis XV range. |

| 1893 | May, Roberts & Co. becomes the British agent for Bourjois et Cie. |

| 1894 | New Products (FRA): Poudre Manon Lescaut. |

| 1895 | Shop opened at 13 Rue de la Paix, Paris. |

| 1896 | Offices opened at 60-62 Rue d’Hauteville, Paris. Boulevard Saint-Martin closed down by 1900. |

| 1898 | E. Wertheimer et Cie takes control of Bourjois. Henry C. Quelch made the British agent for Bourjois. |

| 1909 | New Products (FRA): Cendre de Rose; and La Rose Pompon. |

| 1913 | A. Bourjois & Co., Inc. founded at 25 Broad Street, New York. |

| 1916 | A. Bourjois & Co., Inc. moves to 35 West 34th Street, New York. |

| 1919 | A. Bourjois et Cie Ltd. founded at 66 Carter Lane, London. |

| 1922 | A. Bourjois et Cie (Australasia) Ltd. established at 315 Pitt Street, Sydney. New Products (FRA): Mon Parfum. |

| 1923 | Bourjois assets transferred to Wertheimer Frères. Paris store moves to 28 Place Vendôme. New Products (UK): Ashes of Roses Lipstick; and Ashes of Roses Vanishing Cream. |

| 1924 | A. Bourjois et Cie Ltd. moves to 4 Water Lane, London. New Products (UK): Ashes of Roses Toilet Soap; and Ashes of Roses Baby Powder. |

| 1925 | A. Bourjois et Cie (Australasia) Ltd. opens an agency in New Zealand. |

| 1926 | London factory opened at 71-73 Carter Lane. New Products (US): Cold Cream Poudre Java. |

| 1927 | New Products (FRA): Cold Cream au Citron. |

| 1928 | Radio programming begins in America. New Products (US): Evening in Paris. New Products (FRA): Crème de Toilette Mon Parfum; Poudre Compacte Mon Parfum; Fard Compact Mon Parfum; Raisin Mon Parfum; and Compact Pastels. |

| 1929 | A. Bourjois (New York) and Woodworth, Inc. merged into International Perfume. New Products (FRA): Soir de Paris. |

Continued onto: Bourjois (post 1930)

First Posted: 16th January 2023

Last Update: 28th June 2024

Sources

The American perfumer & essential oil review. (1906-1955). New York: Robbins Perfumer Co. [etc.].

Bourjois. (c.1928). L’art de la toilette [Booklet]. London: Author.

The chemist and druggist. (1859-) London: Morgan Brothers.

Pradal, M. P. & Malepeyre, M. F. (1863). Nouveau manuel complet du parfumeur: Contenant des notions sur les matières premières employées dans cet art. Paris: Encyclopédique de Roret.

Stamelman, R. H. (2006). Perfume: A cultural history of fragrance from 1750 to the present. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc.

Vangreveninge, V., & De Feydeau, É. (2013). La beauté à l’accent français: Depuis 1863. Paris: Editions du Chêne, Hachette Livre.

Joseph-Albert Ponsin [1842-1899].

1863 Blanc Ponsin.

1887 Bourjois Polvo Arroz de Java (Puerto Rico).

1891 Bourjois Parfumerie Louis XV.

1891 Bourjois Poudre de Riz de Java.

1892 Bourjois Parfumerie Louis XV.

1892 Bourjois Poudre de Riz de Java (UK).

Bourjois Poudre de Riz de Java.

1893 Bourjois exhibiting at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago. Poudre de Riz de Java was available in selected stores in the United States no later than 1894.

1895 Bourjois Poudre de Riz Manon Lescaut.

Bourjois Poudre de Riz Manon Lescaut.

-

1896 Bourjois Poudre Manon Lescaut.

1896 A. Bourjois et Cie (UK)

1897 A. Bourjois et Cie.

Ernest Wertheimer [1852-1927].

1898 Bourjois factory at 22 Rue de la Gare.

1899 A. Bourjois et Cie.

1899 Bourjois Java Powder (UK).

1907 Bourjois products (US).

1911 Bourjois perfumes and brilliantines (UK).

1914 Bourjois Marguérite Carré (Austria).

1914 Anthony Hordern catalogue which includes products from Bourjois (Australia).

1916 A. Bourjois & Cie.

1916 Henry C. Quelch (UK).

Bourjois Rouge Rosette Brune.

1919 Bourjois Java Face Powder illustrated by Ralph Barton [1891-1931] (US).

1920 Bourjois Java Face Powder (UK).

1921 Bourjois trade advertisement (UK).

1921 Ashes of Roses and Cendre de Roses (UK).

1923 Bourjois at 28 Place Vendôme, Paris. Architect: Brillaud de Laujarinère. The arched opening of the older building has been filled in with new stone work containing a black-painted window and entrance.

Ernest Beaux [1881-1961].

1923 Bourjois Ashes of Roses and Pierre Wertheiner’s racehorse Epinard (UK).

1923 Trade advertisement for Bourjois Ashes of Roses Lipsticks (UK).

1923 Bourjois Java Face Powder – Peaches, and Peaches and Cream shades (US).

1924 Bourjois Mon Parfum and Poudre Mon Parfum.

1924 Bourjois Manon Lescaut (US).

Bourjois Peaches and Cream Face Powder (US).

1925 Products made by Bourjois.

1925 Bourjois Mandarine (US).

1925 Trays of pastels in the Pantin factory.

Les Secrets de Babette.

Germaine Beaumont [1890-1983].

1925 Bourjois stand at the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs held in Paris in 1925. This temple of beauty contained a gold statuette of a naked woman standing on a column. Shelves containing Bourjois products are arranged on either side of the entrance.

1925 Bourjois ‘Babette fait des emplettes’.

1926 Bourjois Mon Parfum and Powder.

1926 Bourjois Cold Cream Poudre Java (US).

Bourjois Cold Cream Poudre Java Box.

1926 Bourjois Rouges (US).

1928 Bourjois Raisin Mon Parfum.

1928 Bourjois Mon Parfum Perfume, Compact and Lipstick (Austria).

1929 Bourjois Ashes of Roses (UK).

1929 Bourjois Soir de Paris.

Bourjois Soir de Paris Powder Box

1929 Ashes of Roses series (New Zealand).

1929 Bourjois Ashes of Carnations (UK).