Tokalon

Continued onto: Tokalon (post 1930)

In 1912, a number of French and German newspapers posted reports of police warnings about the activities of Harriett Meta Smith and the Dr. Turner Company, both operatives affiliated with the To-Kalon Manufacturing Company based at 7 Rue Auber, Paris.

The Paris address for To-Kalon might suggest that the company was French. However, it actually American, founded (capital US$5,000) in Syracuse, New York State in 1907, which had been operating in France from 1908. Its primary stockholder was E. Virgil Neal, a shonky businessman known in the United States for hypnotism exhibitions and for dubious health cures and patent medicines.

Above: 1900 E. Virgil Neal as the hypnotist X. LaMotte Sage.

These activities had bought him to the attention of the American Medical Association (AMA) who described him as ‘A prince of quakery’.

A PRINCE OF QUACKERY

E. Virgil Neal is a picturesque figure in the world or quackery. He came into the limelight in 1905 as president of the “Force of Life Chemical Company.” This fraudulent concern was investigated by the federal authorities from whom it received a heavy coat of whitewash when it was found that an influential New York politician—Gen. Janies R. O’Beirne—was connected with it. The publicity given, however, proved its undoing. During the same period, Neal, also conducted a bank which is said to have furnished capital for small publishing houses, the loans mostly being paid by advertising space in the publications. Previous to his connection with the Force of Life Company, Neal conducted the “New York Institute of Physicians and Surgeons,” which the government declared fraudulent. He was also connected with the “Columbia Scientific Academy” which purported to be a “school” of palmistry. Earlier still, Neal is said to have traveled over the country under the alias, X. LaMotte Sage, giving exhibitions of hypnotism to ten-cent audiences. After the Force of Life concern went out of existence, Neal organized the Neal Biscuit Company which later changed its name to the American Health Products Company. At present, we find X. LaMotte Sage, president of a fake concern, the “New York Institute of Science,” which gives correspondence courses in hypnotism and magnetic healing.(The propaganda for reform, 1912, p. 1961)

Contributing to Neal’s successes was his keen understanding of business practices. He had attended the C. W. Robbins’ Central Business College in Sedalia, Missouri and had taught there after graduating (Conroy, 2007, p. 15). He subsequently wrote a well regarded and highly successful book on banking and bank accounting and another on bookkeeping that were used in educational institutions across the United States. Neal’s business acumen meant that he knew how to set up systems to hide his finances, minimise the tax he had to pay, while helping to protect him from creditors and law suits. Unfortunately, it also makes unravelling his various business interests very difficult.

A lot of Neal’s early business in proprietary lines and patent medicine was done by mail with customers responding to advertisements placed in newspapers and magazines. Neal made good use of the U.S. Postal Service in the United States and did the same thing when he began operations in Europe and Britain in 1908, and further afield in places like Australia from 1909. The creation of the Universal Postal Union in 1874 made it a lot easier for mail to be sent between countries. Neal could set up a base in a capital city and then use it as a postal address for advertisements placed in newspapers in far flung places.

The founding of To-Kalon, which loosely translates as ‘the beautiful or the good’ in Greek, saw Neal expand his activities into cosmetics including perfumes and toiletries. Potentially these could be as lucrative as the other products Neal sold and could be promoted using similar methods. They were also less likely to get Neal into problems with regulatory authorities or organisations like the AMA. Given the cachet associated with French cosmetics, particularly French perfumes, this may have been why Neal decided to open operations for To-Kalon in France.

Harriett Meta Smith

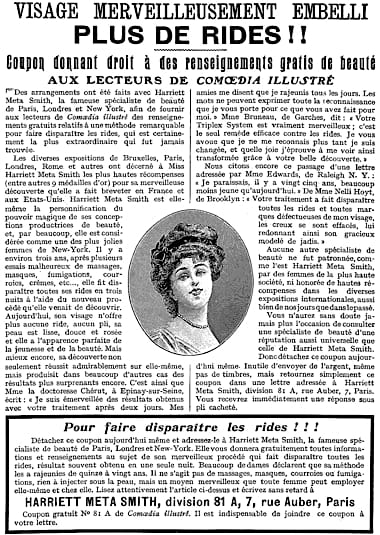

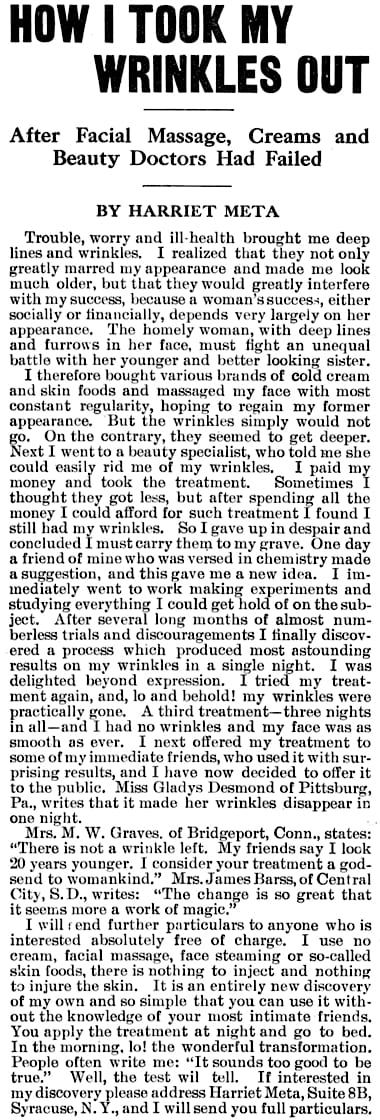

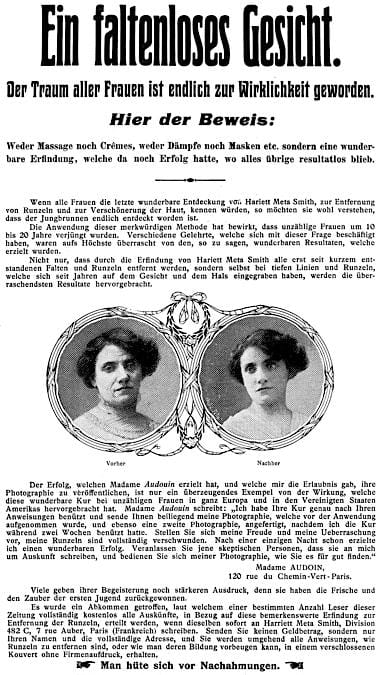

Most of To-Kalon’s early cosmetic advertisements featured Harriett Meta Smith [1884-1934] promoting the Harriett Meta Smith Triplex System, the beauty treatment program featured in the previously mentioned police warning, Harriett Meta’s Gold Medal Hair Tonic, or Harriett Meta’s Milk of Roses.

Smith, whose real name was Harriett Meta Meister, was one of the incorporators of the To-Kalon Manufacturing Company when it was founded in the United States and it is possible that she was the main reason why Neal first got interested in cosmetics. The relationship between Smith and Neal was more than just business as the couple were married in 1911, after Neal divorced his first wife, Mollie H. Hurd [1873-1944]. The To-Kalon Manufacturing Company was not the only business venture that Harriet shared with Neal. She was also involved in the To-Kalon Corset Company, selling Metabone Keepshape Corsets.

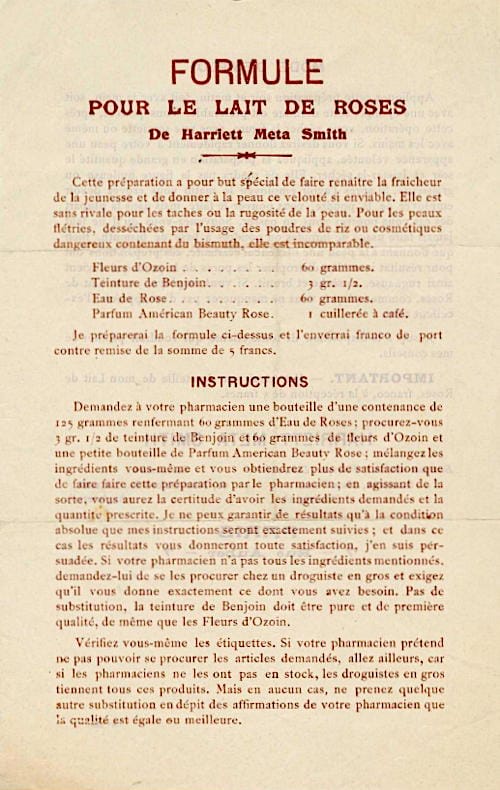

To-Kalon Manufacturing Company advertisements featuring Harriett Meta Smith were frequently disguised as articles offering free beauty advice with no mention that they had been paid for by To-Kalon. A common sales technique used in these ‘articles’ was to supply the reader with a formula for a beauty product along with instructions on how to make it at home. The details of the formula could be included in the article but were more often sent to the reader by mail on request. The catch was that the recipe required an ingredient that was only produced by To-Kalon.

Above: Formula for Lait de Roses from Harriett Meta Smith along with instructions (France).

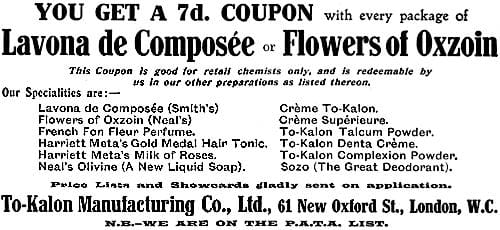

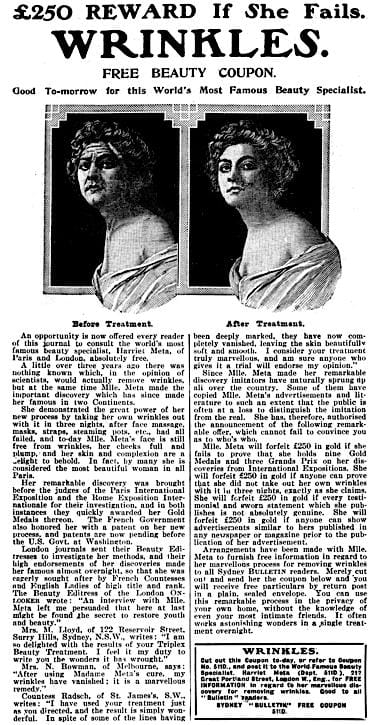

Harriett Meta’s Milk of Roses required To-Kalon’s Flowers of Oxzoin and Harriett Meta’s Gold Metal Hair Tonic used Lavona de Composée, also only made by To-Kalon. Both of these ingredients were analysed in American laboratories. Lavona de Composée was found to be made from alcohol, salicylic acid, glycerin, a saponin-like substance (probably quillaja extract), oil of bay, and water. Flowers of Oxzoin was composed of rose water coloured with cochineal, with added glycerin, and zinc oxide (Wiley, 1914).

Women who were unable to buy the essential ingredients or unwilling to go to the effort of making up the recipe could always buy the actual product, either way To-Kalon profited.

This ruse also applied to the Harriett Meta Smith Triplex System which required Harriett Meta’s Milk of Roses, Harriett Meta’s Dyspepsia Skin Food or Crème To-Kalon, Crème Supérieur, and Poudre Fascination.

Any women that responded to one of To-Kalon’s advertisements also supplied To-Kalon with an address that To-Kalon could use to post additional offers or inducements, a common tactic used in the mail-order business.

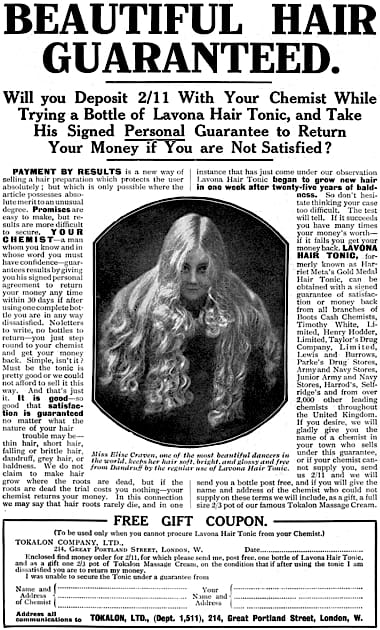

To-Kalon also made liberal use of selling techniques such as gifts, guarantees and coupons to induce sales, more so than most other cosmetic companies.

Above: 1909 To-Kalon product list (UK).

Transition

During the 1910s, To-Kalon changed its name to Tokalon and began to put its more dubious selling and advertising practices behind it. This does not mean that Neal reformed. He simply exchanged the falsehoods associated with promoting patent medicines for the hyperbole that commonly accompanied selling cosmetics.

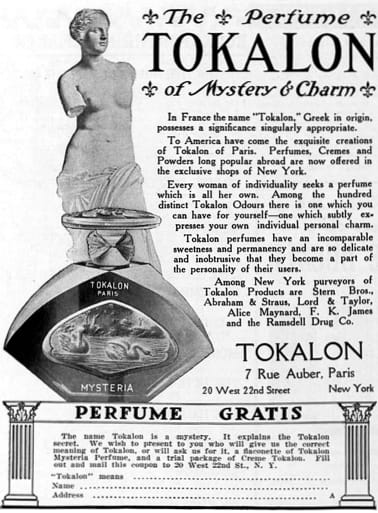

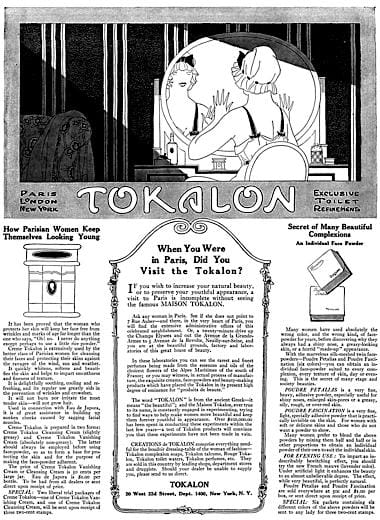

The first of Neal’s companies to take on the unhyphenated name was Tokalon, Ltd. (capital £1,000) founded at 212-214 Great Portland Street, London in 1912. It took over the assets of To-Kalon Manufacturing Co., Ltd. which had opened offices at 61 New Oxford Street, London in 1908. A similar change took place in the United States with the founding of Tokalon, Inc. at 20 West 22nd Street, New York in 1914.

The situation in France is not as clear. The Société To-Kalon Manufacturing Company seems to have been operating out of Neal’s Parisian apartment at 7 Rue Auber, Paris since 1908 and may have become the Société Tokalon by the time a Tokalon factory was opened at 5 Route de la Révolte, Neuilly-sur-Seine in 1913. Unfortunately, I do not have records for the Société Tokalon until it became the Société Anonyme Tokalon (capital ₣1 million) in 1923.

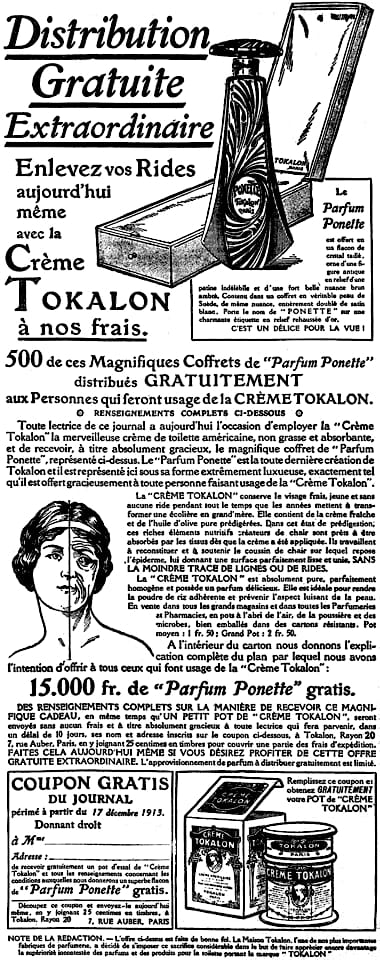

The new name was also extended to To-Kalon products which were changed to Tokalon starting in December, 1912.

Above: 1914 Tokalon Coffret consisting of Comprimé de Poudre Tokalon, Sachet Parfume Tokalon, Crème Tokalon, Parfum Petalais, Parfume Ponette, Poudre Les Fascination de Tokalon, and Parfum Tokalon Tong. (France)

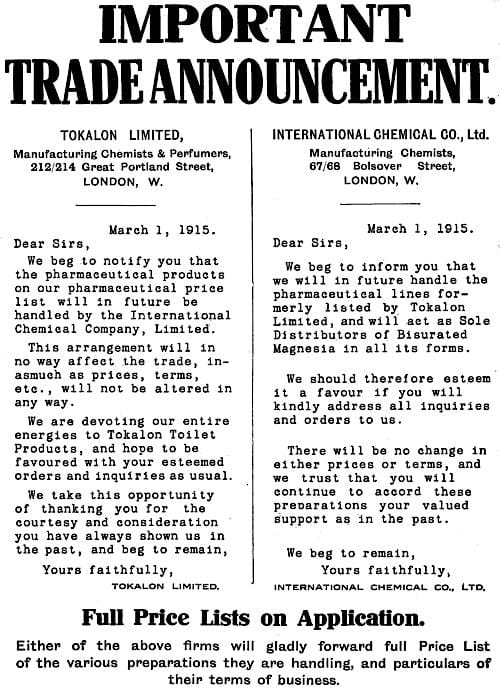

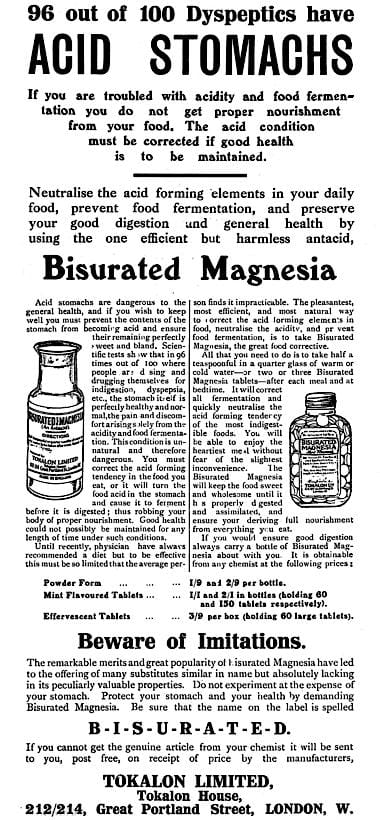

In order to make Tokalon cosmetics more legitimate, Neal also began separating Tokalon cosmetics from his patent medicines and other proprietary lines by placing them in separate companies. For example, Bisaturated Magnesia, a cure for dyspepsia originally marketed through Tokalon, Ltd. in Britain, was transferred to the International Chemical Company, Ltd. when it was founded in London in 1915.

Above: 1915 Trade announcement for the creation of the International Chemical Co., Ltd. which will now handle all of Tokalon’s pharmaceutical products (UK).

The separation of cosmetics from Neal’s other lines took longer in the United States with a number of patent medicines still being sold there by Tokalon until the International Consolidated Chemical Corporation was founded in Dover, Delaware in 1919. This included some hair loss remedies – Salithol, Petresol, and Orathol – some credited to Virgil of Paris, the first time Neal puts his name on a cosmetic.

Virgil Salithol: “[The] treatment has as its base, the juice of the rare and little known Pernambuco Shrub of South America, which grows new hair with utterly amazing rapidity.”

Virgil Petresol: “[Q]uickly neutralises the harmful acid secretions and protects the delicate hair roots from inflammation, thereby stopping the hair from falling and producing a new hair growth. It also renders the hair exceedingly soft and glossy.”

Orathol: “[I]s poisonous to microbes, and means their complete destruction, … [I]ts use for a week or ten days is sufficient for you to notice a remarkable improvement in the condition of the hair and scalp.”

One cosmetic that did not make it from To-Kalon into Tokalon was CIre Aseptine. It was introduced by the To-Kalon Manufacturing Company (France) in 1912 but was not advertised as one of their products. Advertisements claimed that it had a ‘vegetable base’ but available evidence suggests that it was a cold cream and, although it contained herbs, its base was Vaseline/petrolatum. Over the years it was promoted as a cleanser, a base for face powder and as a night cream.

Above: 1919 Cire Aseptine.

CIre Aseptine was joined by Poudre Aseptine in the 1920s. In the 1930s, the range was sold through the Laboratoire Aseptine based at 7 Rue Auber, Paris, the address for Tokalon. In Britain, CIre Aseptine was produced by International Chemical, another Neal company.

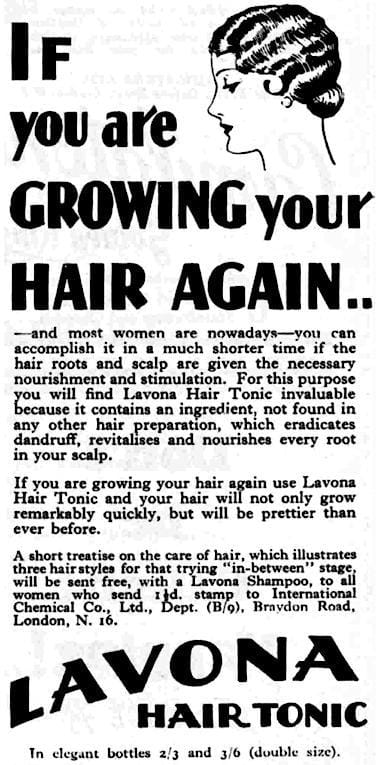

After 1914, any references to Harriett Meta Smith disappeared from Tokalon’s advertising and product range. For example, Harriet Meta’s Gold Medal Hair Tonic became Lavona Hair Tonic and Harriet Meta’s Milk of Roses became Floxoin Lotion. Other Harriett Meta Smith products, such as Harriet Meta’s Dyspepsia Skin Food, simply disappeared. Very strangely, Neal would resurrect her name in 1939 when he introduced a new American cream into the French market – Harriet Meta’s Face and Skin Rejuvenator.

This does not mean that there was a personal rift between Harriett and E. Virgil Neal. That would come later. At some stage she divorced Neal so that he could marry Renée Pauline Bodie [1873-1982] in 1924. Harriett also remarried, taking Albert John Denby as her husband in London in 1932. She appears to have died soon after, in December, 1934.

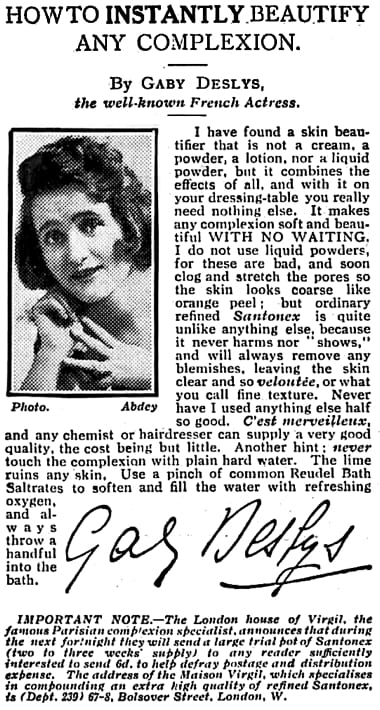

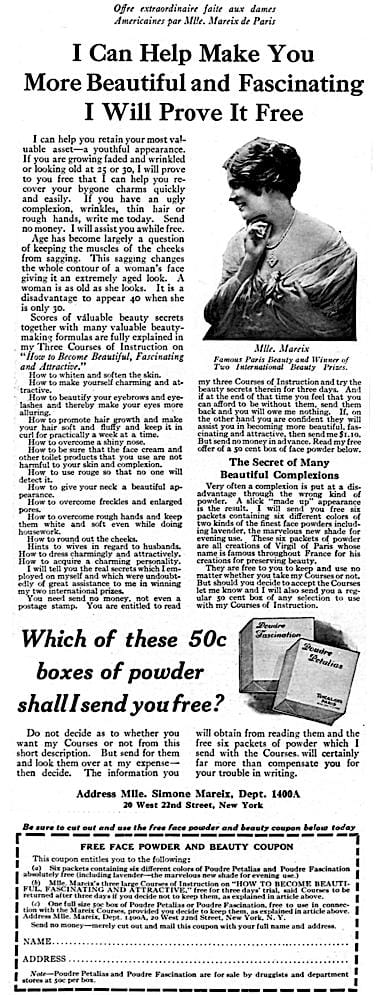

Harriett’s role in promoting Tokalon was initially taken over by a Mademoiselle Simone Mariex, spruiked as ‘a famous French Beauty specialist’ but Tokalon also ran advertisements offering beauty advice from other women as well as endorsements from a number of actresses.

Above: Simone Mariex (second from left) the French entrant for the first International Beauty Contest held in Folkestone in 1908.

Some commentators were rightly cynical about the beauty advice offered by beauty authorities like Simone Mareix.

Yet another beauty doctor has come to town. Her name is Simone Mareix. Once she was a plain ordinary-looking woman, now she is the “well-known Parisian actress, winner of International Beauty prizes—Paris, 1914, England, 1913, surrounded by luxury and the evidences of wealth.” Like all the rest of the discoverers of beauty treatments, her heart bleeds for her plain sisters, and she proposes to reveal the “remarkable secret methods by which she obtained her marvellous beauty” free of charge to the unfortunate ones. She sends them a course of instruction. To carry it out it is necessary to use Santonex, Levathol, Crème Tokalon, Tolomak’s Beauty Paste, Japanese Ice Pencils, and Poudre Fascination, to be obtained from the chemists, at a total cost of 23s. 11d. Not every woman can afford to pay so much for beauty, so Mlle. Simone has devised a coupon scheme whereby the poor and plain may by inducing the plain and wealthy to purchase Poudre Fascination ultimately get their own toilet-tables furnished for nothing.

(Truth, December 9, 1914, p, 1036)

As well as an assortment of ‘beauty experts’ and actresses, Neal also invoked a range of ‘eminent’ doctors and professors to sell Tokalon cosmetics, sometimes using different names to sell the same product in different countries. I have been unable to determine if of these individuals existed but note that there are always people willing to sell the use of their name for the right price.

Various tactics were also used to get chemists to stock Tokalon products in their shops, such as the one outlined below:

In an article under the heading, “Beauty Bunkum,” we told of the curious business, carried on through advertisements, of Miss Simone Mareix. As she recommended an astonishing number of strange toilet preparations at large prices, we assumed that the products of her “free” treatment arose from the sale such articles. Proof comes to us in the shape of a cheque for 10s., sent to a chemist under cover of a remarkable letter from Tokalon, Limited, 212-214, Great Portland Street, W., who are evidently the proprietors of those weird toilet preparations. In their letter they tell the chemist the cheque is not “from father,” but is to induce him to make a window show of their “high grade toilet specialities.” They said they had “a wonderful secret system of advertising”; we are, alas! afraid we have given the show away, and it is secret no longer. Ladies, they wrote, would be swarming into that chemist’s shop to buy Tokalon—and Santonex and Levathol and Witch Hazel and Japanese Ice Pencils. All the shopkeeper need do was to cash the cheque for 10s., send an order for about £10 worth of goods—and wait for the rush. But he has never cashed the cheque, nor has he ordered the quaint and curious goods. And he was wise, for not one of the funny things has ever been asked for in his shop!

(‘Beauty Bunkum,’ 1916)

Products

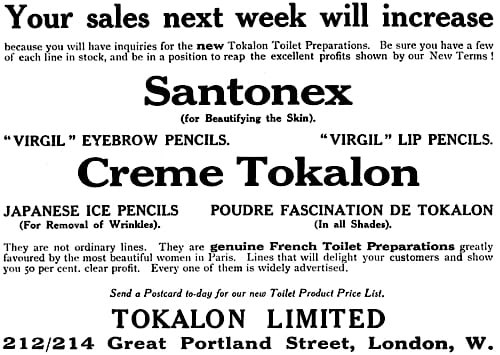

A number of new cosmetics were introduced into the Tokalon range just before the First World War including Virgil Eyebrow Pencils, Virgil Lip Pencils, Rouge Fluide, Santonex, Eau de Japora, Cirolate, Parinol, Tolomak’s Beauty Paste, and Japanese Ice Pencils. Some of these, like the hair growth preparations already mentioned, were credited to Virgil of Paris, particularly so if they were sold in the United States. There are also references to a Maison Virgil in some British advertisements listed at 67-68 Bolsover Street, London, the address of the International Chemical Company.

Above: 1914 Trade promotion for Santonex, Virgil Eyebrow Pencils, Virgil Lip Pencils, Creme Tokalon, Japanese Ice Pencils, and Poudre Fascination de Tokalon (UK).

Information on many of these lines is sparse. Santonex appears to have been type of wet white but made as a solid rather than a liquid. It came in a box in two shades – Light, and Dark – with a sponge that was used to wet and then apply the powder. It was recommended for use on the body as well as the face. Mixing the Dark and Light shades together would have helped match the colour to a person’s skin tone but I doubt that it would have ‘defied detection’ as claimed unless used at night in dim light.

Virgil Santonex: “Not a cream, not a powder, but a wonderful new Parisian creation that immediately suppresses the appearance of practically all imperfections of the skin and complexion, enlarged skin pores, shiny noses and marks of age, and makes one look almost years younger.” Shades: Light, and Dark.

See also: Liquid Face Powders

Eau de Japora and Japanese Ice Pencils were both astringents. The Ice Pencils were to be drawn along facial lines to lift and remove wrinkes while Eau de Japora was to be used more generally to close enlarge pores.

Eau de Japora: “A liquid astringent used to reduce enlarged or naturally large pores.”

Japanese Ice Pencils: “To use as a pencil along the lines of the wrinkles. A deposit remains which acts as a wrinkle eradicator. Removes premature facial lines.”

See also: Skin Tonics, Astringents and Toners

Virgil Cirolate was advertised as containing lemon juice which, if true, would have meant that it acted as a mild exfoliant and bleach.

Virgil Cirolate: “It can be used freely on the most tender or delicate skin, and always leaves the complexion beautifully clear, smooth, delicately tinted, and roselike.”

See also: Bleach Creams

Lips could be coloured with Virgil Lip Pencils which, like Virgil Eyebrow Pencils, came in metal holders, or use Rouge Fluid, a liquid rouge. Rouge Fluid could also be used to add blush to the cheeks or but women could also use Comprimé de Rouge Fascination, a compressed powder.

Unfortunately, I have no information on the composition of Vigil Parenol or Tolomak’s Beauty Paste, the later credited to an unknown Monsieur Tolomak.

Virgil Parinol: “Rubbed occasionally on the face, it quickly clears the pores, and not only keeps the skin free from wrinkles, but brightens the dullest complexion.”

Tolomak’s Beauty Paste: “[W]onderfully assists in making prematurely o!d and wrinkled faces look more youthful and beautiful.”

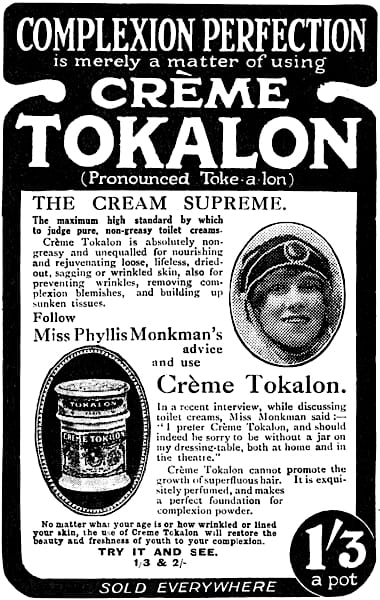

These cosmetics joined existing Tokalon lines, the most important being Crème Tokalon and Poudre Tokalon. Versions of these two lines differed between Britain and Europe and the United States in the 1910s possibly due to the outbreak of the First World War in July, 1914, and the fact that America did not enter the war until April, 1917.

Crème Tokalon

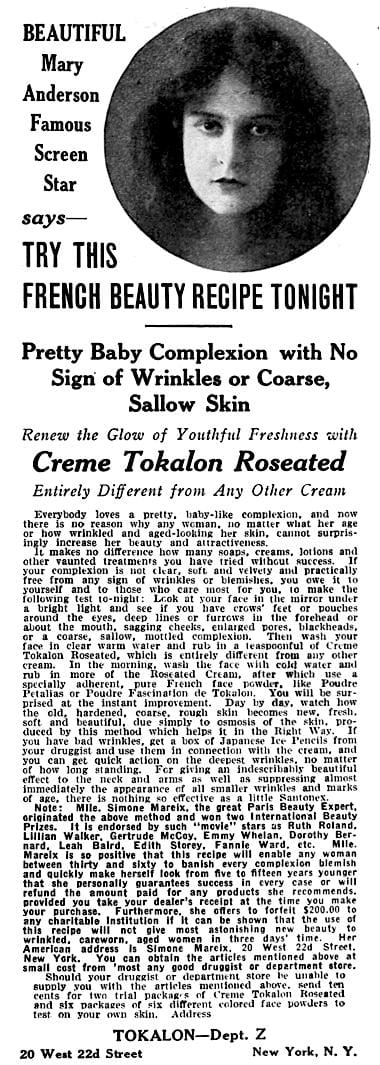

By 1917, Crème Tokalon was being produced in four different forms in the United States – Crème Tokalon (non-greasy, and slightly greasy) and Crème Tokalon Roseated (non-greasy, and slightly greasy).

Crème Tokalon (non-greasy) was a vanishing cream said to be made with predigested dairy cream and olive oil which Tokalon claimed gave the cream rejuvenating qualities. Initially recommended for both evening and morning treatments it would later be primarily used as a base for powder. Evidence suggests that the cream did contain both olive oil and fresh cream but they collectively made up less than 1% of the final mixture.

Crème Tokalon: “It contains pure pre-digested dairy cream and olive oil—those rich tissue building food elements which the flesh needs. In their pre-digested state they are ready to be instantly absorbed by the tissues They build up and immediately sustain the underlying cushions of flesh, giving it a perfectly smooth and even surface over which it is impossible for the skin to wrinkle or sag.”

The slightly greasy form of Crème Tokalon was probably a type of cold cream. It was also said to contain predigested dairy cream and olive oil. Like other cold creams it was initially suggested as a skin cleanser but it would later be recommended as a night cream.

In 1916, Tokalon added Crème Tokalon Roseated in non-greasy and slightly greasy forms into its American range. Mademoiselle Mariex claimed that pure roseated creams were a French beauty secret that produced incredible results through the process of ‘skin osmosis’. She advised women that they could use ‘any good roseated cream’, a typical Tokalon ploy as I doubt druggists would have any others in their inventory apart from Tokalon.

I do not know how these roseated creams differed from the earlier forms of Crème Tokalon but it is possible that Tokalon just added colour to help to help give sallow skin a rosy glow; i.e., it would turn Crème Tokalon into a tinted foundation.

The slightly greasy (i.e. cleansing) version of Creme Tokalon was available in Europe and Britain in the 1910s but it was not widely advertised until the 1920s. There is also no sign of either a roseated or a rose-coloured version of Crème Tokalon there until then as well.

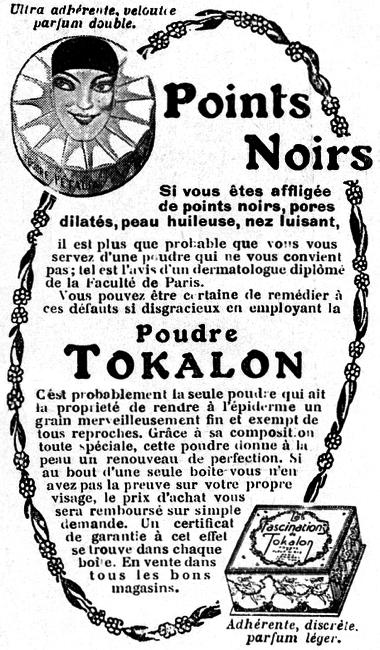

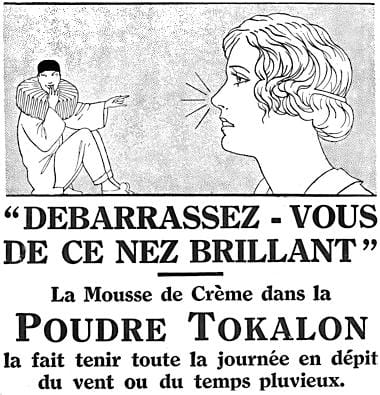

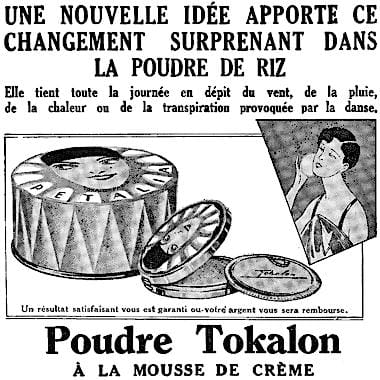

Poudre Tokalon

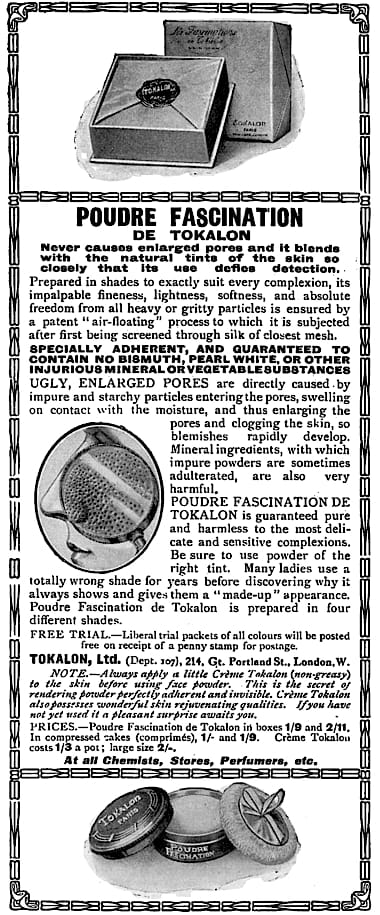

Tokalon sold two face powders in the United States through to the 1920s – a light, fine Poudre Fascination, and Poudre Petalias for women that wanted something more covering. Both powders came in six shades and, like Santonex, Tokalon suggested that women could blend the two shades together to produce something better suited to their skin type. Tokalon also sold a compressed powder but this only appears to have been available as Poudre Fascination Comprimés

Poudre Fascination: “[I]s a very fine, light, specially adhesive powder that is practically invisible on the skin. For women with soft or delicate skins and those who do not want a powder to show.” Shades: Lavender, Flesh, White, Pink, Brunette, and Ocre.

Poudre Petalias: “[I]s a very fine, heavy, adhesive powder, especially useful for shiny noses, enlarged skin-pores or a greasy, oily, rough or over-red skin.” Shades: Lavender, Flesh, White, Pink, Brunette, and Ocre.

In Britain and Europe, I can find only references to one Tokalon face powder before 1920 – Poudre Tokalon also known as Poudre Fascination de Tokalon or simple as Poudre Fascination. Like the American version it came loose in boxes as well as compressed cakes (comprimés) but was only available in four shades.

Poudre Fascination de Tokalon: “Blends perfectly with the natural tone of your complexion and defies detection. Imparts the fresh, natural colouring of youth without the slightest suggestion of artificiality or make-up.” Shades: Rachel/Rachel, Naturelle/Natural, Rose/Pink, and Blanche/White.

I also have records for a range of Tokalon toilet powders in the United States – Buda Toilette Powder, Mysteria Toilette Powder, and Petalias Toilette Powder scented with Tokalon fragrances (Parfum Buda, Parfum Mysteria, and Parfum Petalias). Other Tokalon perfumes available at the time included Parfum Dallas and Parfum Ponette. I only have records for some of these lines in Europe and Britain but it seems likely that they were also available there.

1920s

There were a number of developments in E. Virgil Neal’s personal life during the 1920s, most noticeably the previously mentioned third marriage to Renee Pauline Bodier in 1924 and the birth of a son, Xenophon LaMotte Neal [1924-1996], later in the year. These events may have been the reason why Neal decided to build a large villa in the hills of Gairaut, north of Nice, which he named the Château d’Azur.

Above: 1930 Château d’Azur designed by architects René Gaujoin and Raphël Argentino with interiors by René Boyer.

The chateau was a place of business as well as a private residence which allowed Neal write off some of its expense. These business interests included the construction and operation of a laboratory built near the chateau. Neal would later sell the entire estate to Tokalon.

Above: Laboratory building at the Château d’Azur.

Neal made occasional trips back to the United States between the two world wars but his business and personal interests were now firmly centred in Europe. When Tokalon S.A. was established in Paris in 1923 the company was running two factories there, at 131 Avenue Neuilly, and 28 Rue Victor Noir, both in Neuilly-sur-Seine. The Victor Noir site looks to have been moved to 151 Avenue Neuilly by 1925.

Sales of Tokalon declined in America through the 1920s and the company had abandoned the American market by the end of the decade but kept New York on company advertisements along with Paris and London. This was not the case elsewhere and Neal domiciled Tokalon in Panama in 1925 to avoid paying double taxation on royalties coming in from various countries in which Tokalon was sold (Conroy, 2007, p. 122).

Products

By 1920, Neal had largely separated Tokalon from his patent medicine interests and, with only occasional lapses, Tokalon’s advertising through the 1920s became like that of other cosmetic companies. Tokalon’s promotional budget concentrated on two main lines – Crème Tokalon and Poudre Tokalon. The main exceptions to this inn the 1920s were Kijja (1921) and the Mon Château range (1927).

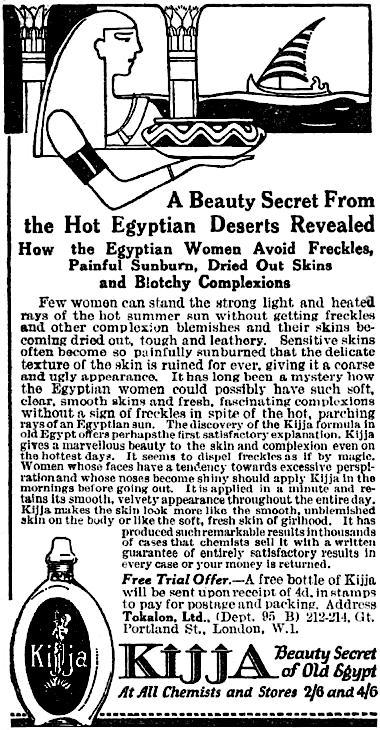

Kijja

Kijja (pronounced Ke-sha) was a liquid powder (wet white) that came in three shades. Cosmetics with an Egyptian theme became very popular in the 1920s following the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb by Howard Carter [1874-1939] in November, 1922 but Kijja predates Carter’s discovery – a happy accident.

Tokalon had tried something like Kijja before with Santonex but Santonex was manufactured as a solid rather than a liquid wet white. Tokalon recommended Kijja be used during the day to protect the skin from exposure to cold, wind and rain but I imagine that, like other powders of its type, it was best suited for use at night.

Kijja: “Gives a new beauty and texture to the skin that is more like the soft white unblemished skin on the body, or like the smooth delicate skin of girlhood. It refreshes and smoothes a tired, wrinkled or lined face, and softens the expression until a woman positively looks ten years younger.” Shades: Rachel, White, and Natural.

Mon Château

Parfum de Mon Château and Poudre de Mon Château both tried to capitalise on the ostentatious luxury of the recently constructed Château d’Azur. They were not promoted as Tokalon lines and only occasionally mentioned Tokalon in advertisements. French trademark documents suggest that Neal intended to introduce a skin cream into the series but I have no evidence that one was ever made.

Parfum de Mon Château came in a bottle inspired by the Château d’Azur with a cheaper and less ostentatious bottle added later.

Above: Box and empty bottle of Parfum de Mon Château.

Poudre de Mon Château came in four shades which, I assume, were the same as the French Poudre Tokalon – Rachel, Naturelle, Rose, and Blanche. Both lines were sold through the Société du Château d’Azur based at Tokalon’s Paris address – 7 Rue Auber. As far as I can tell both lines were only sold in France and seem to have been discontinued by the end of the decade.

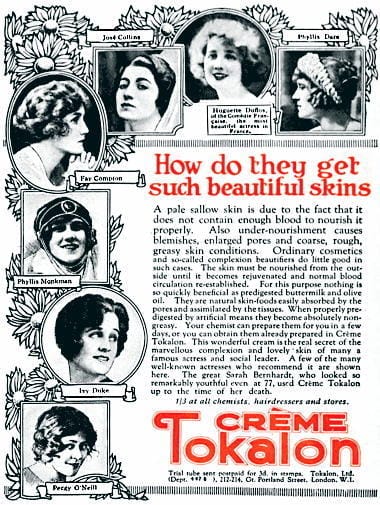

Crème Tokalon

In the 1920s Tokalon returned to promoting the buttermilk and olive oil formulation of its Crème Tokalon, now recommended by a Dr. Grosmand, described as a ‘a noted Parisian skin specialist’. A number of its advertisements from this period used the ‘get the ingredients from the chemist’ selling technique previously used by Harriet Meta Smith to sell her Gold Medal Hair Tonic and Milk of Roses.

Above: 1925 Crème Tokalon (UK).

Tokalon also began marketing Crème Tokalon as a skin food (aliment pour la peau), something other cosmetic companies had been doing for decades and we also get the first references to rose-coloured Crème Tokalon in Britain and France. By the end of the decade Tokalon was selling two versions of Crème Tokalon – a white day cream and a rose-coloured night cream. During this time there were minor changes to the French jars and labels of Crème Tokalon but major changes to those sold in Britain where new curved jars clearly labelled as skin foods appeared in 1929.

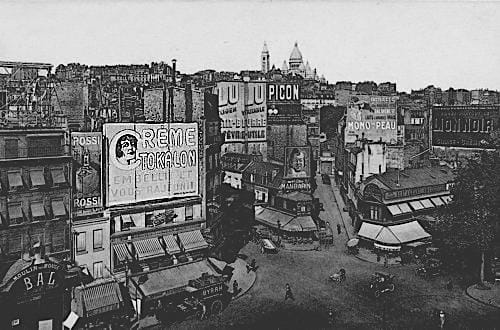

Above: c.1927 Paris billboard for Crème Tokalon. The Basilique du Sacré-Coeur de Montmartre is in the background.

Poudre Tokalon

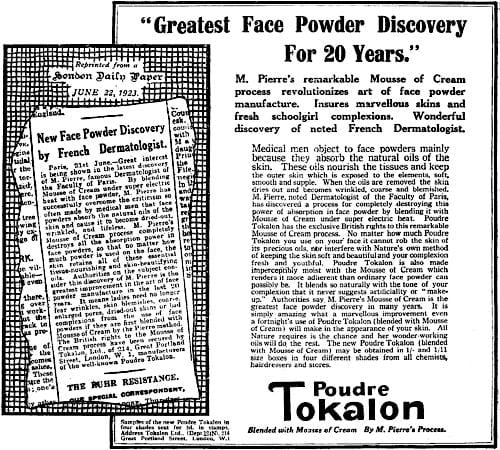

In 1924, Tokalon was granted a patent (British patent: 218154) for manufacturing an oleo stearate of glyceryl made by emulsifying a mixture of dairy cream and olive oil, that had been ‘digested’ with pancreatin, with stearic acid and potassium carbonate. The resulting powder appears to have been used to create a new powder formulation – Poudre Tokalon with Mousse of Cream.

Above: 1923 Poudre Tokalon with Mousse of Creme (UK).

Poudre Tokalon Mouse of Creme: “[S]tays on twice as long; it is lighter, finer, purer. Wind, rain, dancing, or perspiration cannot spoil the smooth perfection it gives your skin.” UK Shades: Rachel, Natural, Pink, and White with Rachette (1924), Light Pink (1925), Ochre, and Mauve (1927) added later.

The British patent suggest that Samuel Archibald Walton was responsible for the invention but Tokalon credited it to a Dr. Pierre, describing him as ‘a noted dermatologist’. The new formulation was said to make the powder more adherent, and prevent shiny noses and greasy-looking skin.

There appear to have been major differences between the mousse of cream powders sold in France and Britain. I have only been able to find references to Poudre Fascination being sold with Mousse of Creme in Britain while Poudre Fascination and Poudre Petalia were both made with Mousse of Creme in France.

The first advertisements I have found for Poudre Petalia (Poudre Petalias in America) appear in France in 1922 with Poudre Petalia Mousse de Crème arriving in 1923. This may also be when the well-known Pierrot powder boxes were introduced. They were sold in other European countries as well but I have been unable to find any evidence of them in English-speaking countries like Britain or the United States.

Other lines

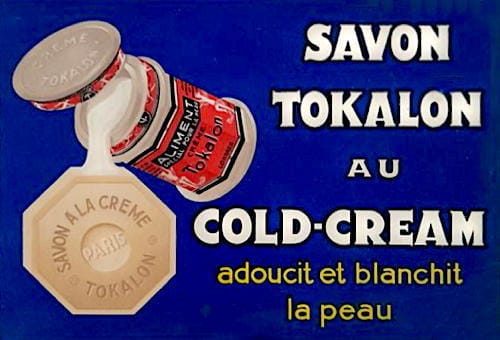

Information on other Tokalon products is sparse but it appears that it continued to sell compact rouges, eyeliners, lipsticks, and a cold cream soap.

Above: Savon Tokalon au Cold Cream.

Rouge Tokalon was packed in aluminium containers and came in four shades – Printemps des Brunes/Brunette, Rouge Oriental/Mandarine, Printemps des Blondes/Blonde, and Reflect de Rose/Raspberry.

In France, Tokalon lipsticks were referred to as ‘crayons lèvres’ rather than the normal ‘rouges à lèvres’ and only came in three shades – Rouge Franc, Rouge Moyen, and Rouge Foncé. I have no information on the case these were housed in or the mechanism used to push the lipstick from the case but I suspect it to be a push-up rather than a twist-up. I also don’t have any records for a Tokalon lipstick in the United States during the 1920s and my first reference to one in Britain only appears in 1929 with a lipstick in a long nickel push-up case. It was a changeable indelible very similar to the lipstick produced by Tangee. Like the original Tangee lipstick, it only came in one shade and used a bromo acid dye so looked orange in the case but turned pink on the lips. I have no references to this lipstick appearing in France.

See also: Tangee

The Tokalon eyeliner (crayon cil) came in three shades in France – Noir, Chatain, and Brun. Again, I have no information on this cosmetic in Britain or the United States.

Timeline

| 1907 | To-Kalon Manufacturing Co. founded in Syracuse, New York State. |

| 1908 | To-Kalon Manufacturing Co. opens a branch in London. |

| 1909 | To-Kalon Manufacturing Co., Ltd. founded in London. |

| 1911 | To-Kalon Manufacturing Co., Ltd. moves to To-Kalon House at 212-214 Great Portland Street, London. |

| 1912 | To-Kalon Manufacturing Co., Ltd. (London) becomes Tokalon, Ltd. New Products: Cire Aseptine (France). |

| 1913 | Tokalon, Inc. founded in New York. |

| 1914 | New Products: Santonex (USA). |

| 1915 | International Chemical Co., Ltd. established in London. |

| 1916 | New Products: Crème Tokalon Roseated (USA). |

| 1919 | International Consolidated Chemical Corporation founded in Dover, Delaware. |

| 1921 | New Products: Kijja (France). |

| 1923 | New Products: Poudre Tokalon Mousse of Creme (France). |

| 1925 | Compania Tokalon Paris founded in Panama. |

| 1927 | New Products: Parfum de Mon Château; and Poudre de Mon Château (France). |

Continued onto: Tokalon (post 1930)

First Posted: 26th January 2025

Sources

Beauty Bunkum. (1916). John Bull. XIX(505), 13.

Cerbelaud, R. (1933). Formulaire de parfumerie (Vol. II). Paris: René Cerbelaud.

The chemist and druggist. (1859-) London: Morgan Brothers.

Conroy, M. S. (2007). The cosmetics baron you’ve never heard of: E. Virgil Neal and Tokalon. Englewood, CO: Altus History.

The propaganda for reform. (1912). The Journal of the American Medical Association. 58(24), 1961-1964.

Truth. (1914). London: Truth Publishing Co,. Ltd.

Wiley, H. W. (1914). 1001 tests of foods, beverages and toilet accessories, good and otherwise. New York: Hearst’s International Library Co.

Ewing Virgil Neal [1868-1949].

1908 Plus de Rides by Harriett Meta Smith (France)

1909 How I took my wrinkles out by Harriet [sic.] Meta Smith (USA).

1910 A wrinkle free face from Harriett Meta Smith (Austria).

1910 To-Kalon Parfum Charmant (USA).

1911 Metabone Keepshape Corsets.

1912 Harriet Meta Smith Triplex System (Australia).

1913 Lavona Hair Tonic (UK).

1913 Crème Tokalon (France).

1914 Tokalon Mysteria Perfume (USA).

1914 Tokalon Bisaturated Magnesium (UK).

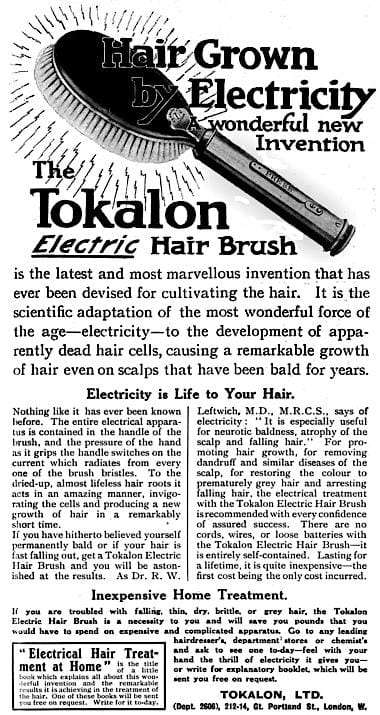

1914 Tokalon Electric Hair Brush (UK).

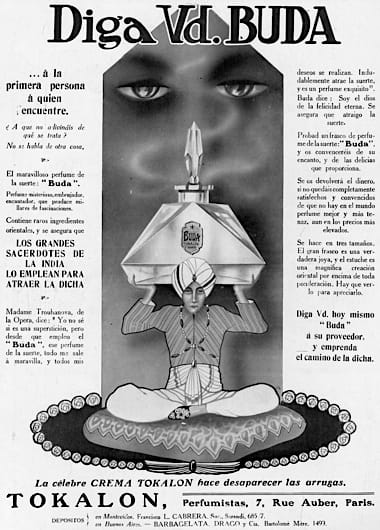

1914 Tokalon Buda Perfume (South America).

1915 Santonex (UK).

1915 Poudre Fascination de Tokalon (France).

1915 Creme Tokalon (USA).

1915 Tokalon Poudre Fascination and Poudre Petalias (USA) both said to be created by Virgil of Paris.

1916 Trade advertisement for Tokalon products including Crème Tokalon, Santonex, Sepalias Shampoo, amd Poudre (Fascitation) Tokalon (UK).

1917 Crème Tokalon Roseated (USA).

1917 Nuxated Iron, another patent medicine (USA).

1919 Crème Tokalon (UK).

1922 Poudre Petalia and Poudre Fasciation (France).

1923 Kijja (UK).

1924 Endorsements for Crème Tokalon (UK).

1926 Crème Tokalon (UK) with new Duplex lid introduced in 1923.

1926 Poudre Tokalon (France).

1926 Poudre Tokalon Compact (UK).

1927 Crème Tokalon (France).

Poudre Petalia Compact.

1928 Poudre de Mon Château and Parfum de Mon Château (France).

Poudre de Mon Château (France).

1929 Trade advertisement for Crème Tokalon Night (rose) and Day Skin food (white) in new jars (UK).

1929 Poudre Tokalon (Petalia) with Mousse de Crème, powder box and compact (France).

1929 Lavona Hair Tonic (UK). This use to be Harriett Meta’s Gold Metal Hair Tonic and is now sold by the International Chemical Co., Ltd.

1929 Tokalon Lipstick (UK).