Tokalon (post 1930)

Continued from: Tokalon

By 1930, Tokalon cosmetics were no longer being made and sold in the United States. As well as the plants in Paris, Tokalon, Ltd., based in Great Portland Street, London, also developed manufacturing facilites there as well. I don’t have any records for when this occurred but operations there may have been extended when company moved to 71 Chase Road, London in 1931. Other factories were developed in places such as Spain and Switzerland but I will concentrate my investigations on product development to France and Britain.

Local manufacturing had a number of benefits for Tokalon, Ltd. It avoided the import duties imposed by the government to protect British industries during the Great Depression which helped keep Tokalon prices competitive. It also allowed Tokalon to benefit from the preferential treatment given by countries in the British Empire to goods manufactured in Britain or other parts of the Empire. The main disadvantage was that Tokalon could no longer claim that its products were fully imported from France.

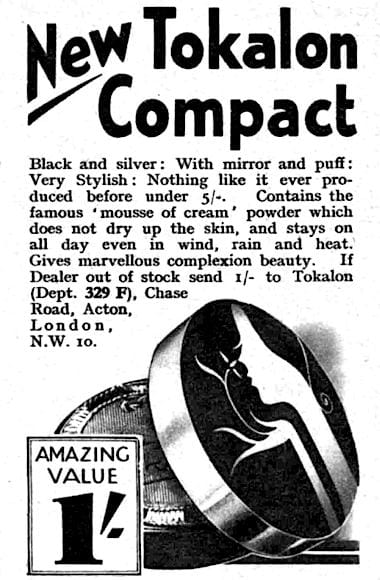

Local manufacturing also gave the British arm of Tokalon a degree of independence that allowed it to further differentiate its product range from that sold in France and the rest of Europe. Previous differences between the Tokalon product range in Britain and France would widen even further. This can perhaps best be seen in Tokalon packaging. New British designs were more likely to use clean, modern lines such as those in the new black and silver nickel compacts it introduced in 1932. French packaging continued to be decorated in the older ‘Arte Nouveau’ inspired patterns.

Above: 1932 Display stand for Tokalon Dragon Fly and Lady’s Head Compacts (UK). Starting at 2/6, the price dropped to 1/- in 1933.

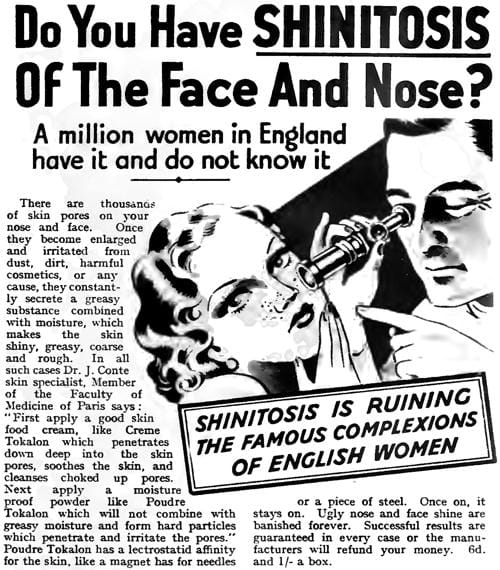

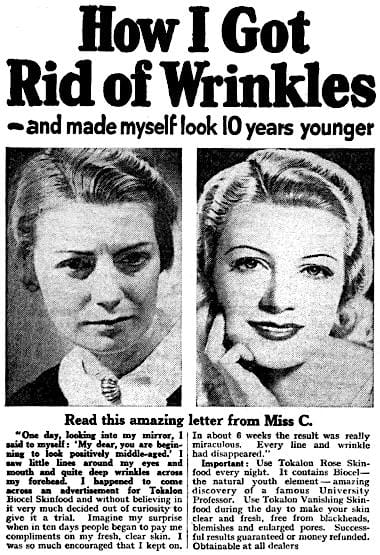

Another difference between French and British Tokalon concerned advertising. Tokalon advertisements continued to use the exaggerated claims, money back guarantees, limited offers, gift coupons, and coffrets it had used in the 1920s but the British company appears to more likely to use American ideas, particularly when it came negative advertising. For example, a 1936 advertisement warned readers about the made up problem of ‘Shinitosis’ a similar idea previously used by Pompeian with its 1935 advertisement concerning the problem of ‘Dermoerosion’.

Above: 1936 Shinitosis cured with Crème and Poudre Tokalon (UK).

See also: Pompeian Manufacturing Company

A more blatant example came in 1938 when British Tokalon copied a 1934 advertisement for Lady Esther’s very successful ‘Bite Test’ campaign.

See also: The Bite Test

Products

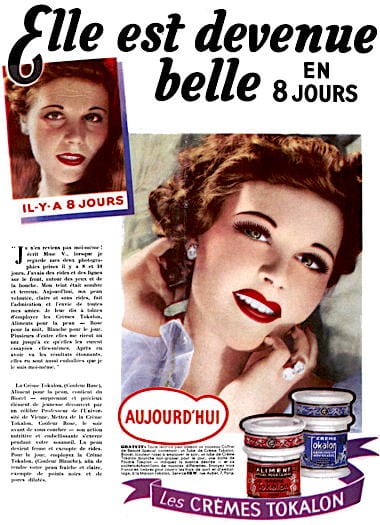

During the 1920s, most of Tokalon’s advertising budget was spent on promoting its skin creams and face powders. This continued through the 1930s with Crème Tokalon undergoing a major reformulation after Biocel was added to the rose-coloured Crème Tokalon in 1930.

Above: c.1933 Tokalon product display at a trade show in Vancouver, Canada.

Crème Tokalon

By 1930, Neal was in his 1960s and Conroy suggests that his advancing age may have prompted him to become interested in the rejuvenation treatments developed by Dr. Serge Voronoff [1866-1951] (Conroy, 2007, pp. 154-155). Rejuvenation treatments using serums and tissues were widely publicised in the 1920s, even Helen Rubinstein [1872-1965] had expressed an interest in them.

See also: Rubinstein and the Rejuvenationists

There is no hard evidence that Neal took any of Voronoff’s treatments but the work of Voronoff and others may have given him the idea for Biocel. Tokalon had long claimed that Crème Tokalon was rejuvenating and the addition of Biocel reinforced this claim.

The patent covering the manufacturing process for Biocel (British Patent No: 365,004; 1932) indicates that it was an extract made from young animal skin cells. Adding tissue extracts to skin creams was a novel idea for the time. This had been previously done with gland extracts but, as far as I can tell, Tokalon was the first cosmetic company to incorporate a non-glandular tissue extract into a skin cream. It predated the later use of embryo extracts and was decades before the use of other tissue extracts such as hyaluronic acid or collagen.

See also: Embryo Extracts

Supposedly developed by Professor Dr. Karl Stejskal of Vienna, Biocel was included in the rose-coloured/rose version of Crème Tokalon. The addition of Biocel also saw Tokalon increasingly marketing its skin creams as skin foods something, Tokalon had started to do in the late 1920s and other cosmetic companies had been doing for decades.

Crème Tokalon Skin Food (rose colour): “It supplies your skin with precious youth-restoring Biocel tissue and nourishes it while you sleep. It will produce an almost unbelievable transformation in your skin even in one night.”

See also: Skin foods

As Tokalon Biocel Skinfood was a type of cold cream it was still advertised as both a night cream and cleanser, traditional roles for creams of this type. The clear-coloured vanishing cream version of Crème Tokalon continued to be promoted as a base for Tokalon Mousse of Cream Face Powder. Tokalon expected them to be used together.

At Night: Apply a liberal quantity of Tokalon Biocel Skinfood to the entire face. Massage gently into the skin with the fingertips, using an upward and outward movement.. Then wipe away excess which carries with it dust an impurities from the pores. For quickest and best results, make a second application and allow to remain on all night; it nourishes your skin while you sleep. If your throat, neck and hands show signs of age you must also use Tokalon Biocel Skinfood on them, otherwise the contrast with your face may become too marked.

Morning: Cleanse the face thoroughly either by washing in warm water or by applying Tokalon Biocel Skinfood. Wipe this off and then apply Tokalon Vanishing Skinfood, which is an absolutely non-greasy cream. It acts as a tonic to the skin and counteracts enlarged pores; prevents the formation of blackheads and pimples. In addition it forms the perfect base for your powder, and for the best results should be used with Tokalon Mousse of Cream Face Powder.(Tokalon brochure, 1933)

See also: Cold Creams amd Vanishing Creams

Poudre Tokalon

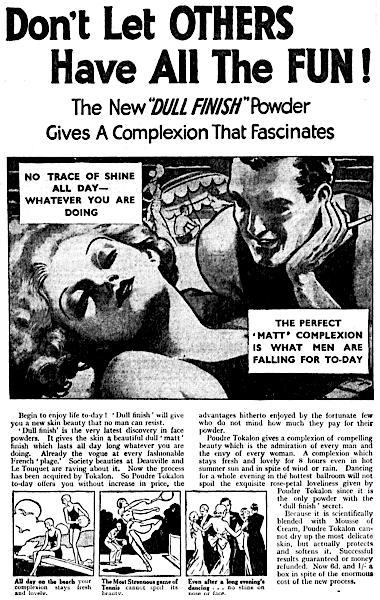

Tokalon continued promoting the advantages of its Mousse of Crème Face Powders through the 1930s. As was the case in the 1920s, this included Poudre Fascination and Poudre Petalia in France but only Poudre Fascination in Britain where it was simply referred to as Poudre Tokalon.

In 1932, the French arm of Tokalon added Poudre PerO for women with oily skin (peau grasse) in a new box. Poudre Petalia was now being recommended for women with dry skin (peau seche) with both powders produced in the same shade range. This is a rare example of Tokalon making allowances for different skin types.

Above: Petalia and PerO powder boxes.

The idea of selecting powder according to skin type was also taken up in Britain at this time but there, Poudre Tokalon (i.e., Poudre Fascination) was recommended for dry skins while women with greasy skin were suggested to use Poudre Tokalon Petalia, the exact opposite of what was suggested in France. Perhaps this is why I have only seen references for Poudre Tokalon Petalia being sold in Britain in 1932 and 1933, none before and none after.

Above: 1933 Poudre Tokalon and Poudre Tokalon Petalia (UK).

Another development in Tokalon face powders occurred in 1935 when the French and British Poudre Fascination was reformulated with Double Mousse of Crève (Double Mousse de Crève) to give the powder a fashionable matt finish (fini mat).

Tokalon also increased the shade range of its face powders during the 1930s. By 1939, shades available in Britain were Natural, Rachel, Rose Natural, Ochre Rosée, Ochre, Rachelle, Peach, Evening Green, Suntan, Brunette, Apricot, and White. Known French powder shades from the 1930a are Naturelle, Rachel, Rose, Rose Ocre, Ocre, Ocre No. 2, Rachel Doré, Péche, Brun-Soleil, and Blanche.

The shade range of Tokalon compact powders was not as extensive. For example, the French Poudre Tokalon Compacte a la Mousse de Crème only came in Blanche, Rose Rachel, Rose Ocre, Ocre, and Rachel Doré shades.

In 1938, British Tokalon came up with a novel idea for getting a seaside tan at home. Readers could send away for Konka Powder (No. 1) which they could mix into their own shade of Poudre Tokalon to get a light tan or bronze effect on the skin. A second powder, Mauvinol Powder (No. 2) could be used in a similar fashion to produce a beautiful effect under artificial light. The promotion was designed to increased powder sales with Tokalon recommending that readers have three boxes of Poudre Tokalon, one for general use, a second for the sports powder, and a third for use in the evening.

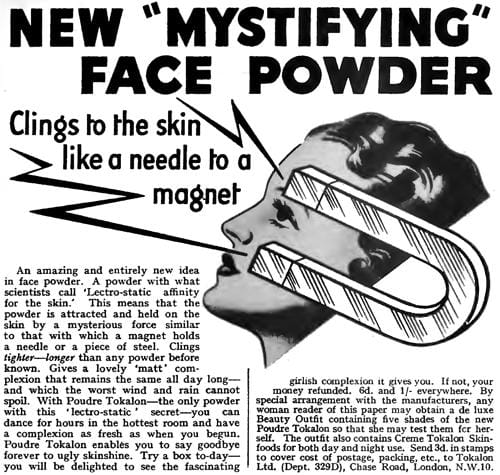

As well as increasing its shade range, Tokalon was always ready to invoke some sort of new scientific or pseudo-scientific feature to encourage sales. For example, it claimed that its powders had ‘lectro-static’ cling in 1936.

Above: 1936 Poudre Tokalon has ‘lectro-static’ cling (UK).

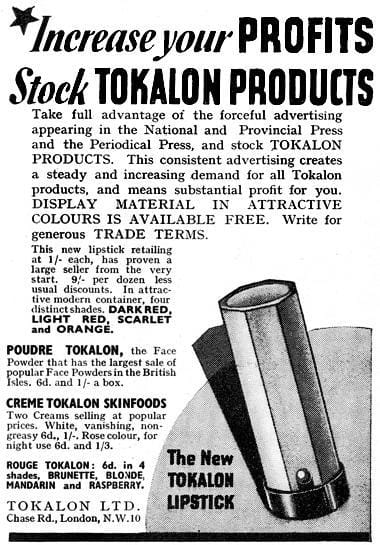

Lipsticks and rouge

Although they never got the marketing attention Tokalon gave to its skin creams and face powders, lipsticks were mentioned more frequently in the 1930s than previous decades. In France, Tokalon referred to its lipsticks as ‘crayons-lèvres’ rather than the normal ‘rouges à lèvres’. They were housed in push-up metal cases and appear to have been indelibles. Shades ranges were very limited – Moyen, Foncé, and Franc in France, Light Red, Dark Red, and Orange in Britain.

Above: 1935 Trade Advertisement for Tokalon Lipstick and Rouge (UK).

In 1936, Tokalon introduced a new indelible lipstick referred to as Crayons-lèvres d’Amour in France and Love Lipsticks or Vitamin love Sticks in Britain. They contained vitamin F and came in a new hexagonal push-up case but still had a limited shade range. In France, the lipsticks were introduced in Moyen, Vif, and Franc shades with Cerise, Cyclamen, and Clair were added by 1938. In Britain, the shades were Light Red, Dark Red, Orange, and Scarlet with later additions including Black (1938) and Orchid (1939). Like others of its type the Black shade was indelible and turned red on the lips.

Tokalon lipsticks were colour coordinated with Tokalon rouges. Starting in 1937, these were said give the cheeks the ‘Fraicheur de la Jeunesse’ (Freshness of youth) in France. Britain they were advertised as Blush of Youth Rouge.

Other cosmetics

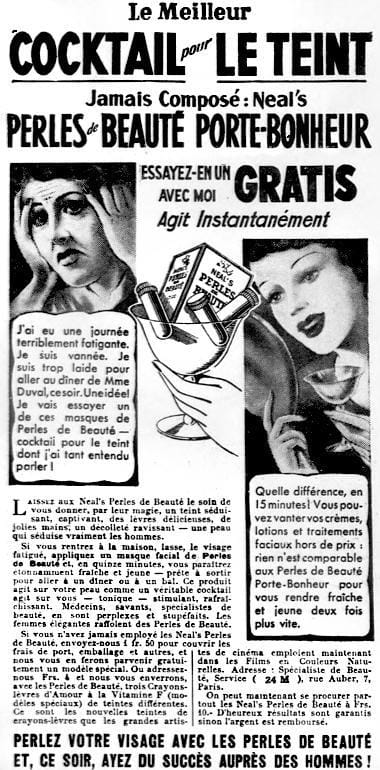

In 1936, Tokalon introduced a new line in France – Neal’s Perles de Beauté – which looks to have been a masque. It came in a screw-top jar which suggests that it was susceptible to evaporation. I can find no trace of it in Britain but Conroy suggested that Neal tried unsuccessfully to launch the product into the United States in 1938 (Conroy, 2007. p. 165).

Neal’s Perles de Beauté: (trans.) “[N]ot a lotion, cream, pills, or powder. Its secret has never been revealed. Beauty specialists, scientists, doctors and magicians are perplexed. Women are crazy about it. From the first contact with your skin, it becomes whiter and softer like velvet.”

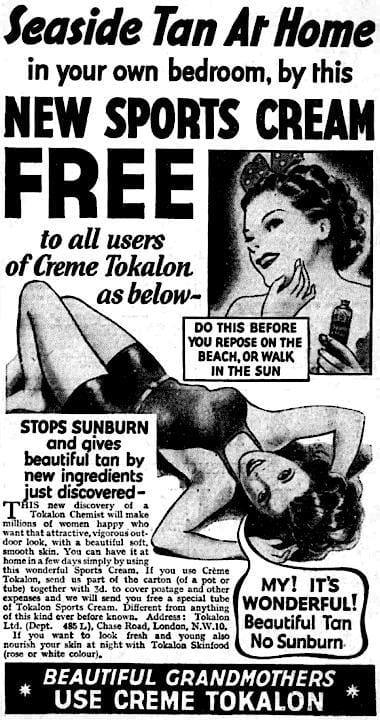

In 1938, Tokalon introduced a sun-care or sports range. I have records for a Tokalon Sports Cream sold in convenient tubes as well as a Tokalon Sports Powder in Britain, and a Creème Sports Tokalon and a L’Huile Sport Tokalon in France. Both products were claimed to act as sun screens.

Tokalon Sports Cream: “Stops sunburn and gives a beautiful tan.”

Tokalon Sports Powder: “Specially created to give outdoor glamour. It is waterproof. you can dive in the sea—still it stays on.” Shades: Capri, Miami, Hawaii, Lido, and Moritz.

Repackaging

In 1938, British Tokalon updated its cartons and the packaging for its products that were sold in tubes but left its cream jars in the bottles it had introduced in 1929.

Above: 1938 New Tokalon packaging (UK).

Some packaging changes also occurred in France. In 1939, the opal cream jars were changed slightly and given simplified labels. For example, the rose coloured Crème Tokalon had its ‘Crème Tokalon alimant special pour la peau’ label restyled and changed to ‘Crème Tokalon pour la nuit’. The boxes for its creams remained largely the same but the French branch of Tokalon may have been thinking about modernising these as well. Harriet Meta’s Face and Skin Rejuvenator that was introduced in France in 1939 came in a box in a similar design to those introduced in Britain the previous year.

War

The fall of France in 1940 created a number of problems for Neal who remained in Europe during the war. Paris was occupied by the Germans and while Nice by the Italians after they joined the war. Manufacturing continued in Paris, but Neal also set up operations in Marseilles and Monte Carlo which joined Tokalon’s other factory Geneva, Switzerland. These factories enabled Tokalon to continue production.

In 1941, Tokalon began manufacturing a new product, Super Crème Tokalon. It was made with the non-greasy, vanishing cream base with Biocel but it was produced in three shades – Blanche, Rose, and Rachel – so would have acted as Tokalon’s first coloured foundation. Tokalon recommended that it could be used both during the day and at night.

In Britain, the Tokalon factory in Park Royal had burnt down in 1941 but a new plant had been established at 450 Basingstoke Road, Reading. This enabled Tokalon to maintained production of many of its products during the war despite the inevitable shortages of workers and materials. One of these shortages may have been imports of Biocel as the British company stopped advertising Crème Tokalon with Biocel in 1942 and did not resume it until 1948. There is also no record of the French Super Crème Tokalon or something similar appearing in Britain during the war.

British Tokalon made a small contributed to the war effort after it got a contract to make Gas Detector Powder in 1944. Unfortunately, as shipping to other parts of the British Empire became increasingly risky, sales in countries like Australia and New Zealand ceased in 1942 for the duration of the war.

Post war

Tokalon S.A. (France) was based at 183 Rue de la Pompe, Paris after the war, having been there since at least 1930. Tokalon, Ltd. (Britain) had been listed at at Avon House, 356 Oxford Street in 1944 but had moved to 24 Gilbert Street, Mayfair in 1949.

E. Virgil Neal died in 1949 but the identity of Tokalon’s new owners is unknown. Conroy suggests that it may have been purchased by the Office pour la Recherche et Étude Cosmétique (OREC) S.A. prior to Neal’s death. OREC had been founded by Auguste E. Baumeister, who ran Tokalon in Geneva, Switzerland, and three partners in 1947 (Conroy, 2014, p. 378). Unfortunately, the financial structure of Tokalon with its numerous legal entities, many designed to help Neal avoid scrutiny and taxation, has made unravelling the ownership of his various businesses after his death very difficult.

Whatever the situation, it does appear that OREC tried to unify the various parts of Tokalon after Neal’s death and it had gained responsibility for the manufacture and sale of Tokalon products in 34 countries by 1955. Product development appears to have been centrally directed by Kurt J. Pfeiffer, OREC’s technical director/company chemist.

Products

Advertising Tokalon in France continued to focus primarily on Tokalon creams and face powders but there appear to have been some changes in the ranges. I can find no trace of Super Crème Tokalon introduced by Neal into France during the war or of Poudre Petalia which had been in the French inventory since at least the 1920s.

Crème Tokalon

Crème Tokalon rose with Biocel, and Crème Tokalon blanche remained French staples after the war. In 1953, Tokalon introduced a third product Crème Tokalon Grasse for women with dry skin types for use during the day.

In Britain things were a little more complicated. At some stage after Neal’s death a dispute occurred between some of the company directors of Tokalon, Ltd. and Neal’s wife, Renée Neal, and son, Xenophon LaMotte Neal. The dispute sent the company into receivership until the parties came to an agreement in 1952. The management dispute may have been responsible for an unusual state of affairs that concerned Biocel.

In 1948, British Tokalon had began advertising once more that its rose coloured Creme Tokalon contain Biocel but this stopped part way through 1949. After this, Tokalon, Ltd. began claiming that its Rose Skin Food (for night use) and Vanishing Cream (for the day) now contained Biocelle which it described as ‘an amazing beauty treasure dug from deep down in the earth’; i.e., nothing to do with animal extracts. Biocel does not appear to have returned to Tokalon skin creams in Britain again until 1955 shortly after Tokalon, Ltd. had become part of OREC in 1954. By then, the company had adopted English names – Vanishing Cream and Rose Skinfood – and there is no sign of the dry skin cream that made its appearance in France.

Above: 1958 Trade advertisement for Chase Biocel Cream.

Biocel disappears from Tokalon creams again in 1957, after it was moved to Chase Laboratories. During the war Chase Laboratories, Ltd. sold Chase Stomach Remedy from its base at 356 Oxford Street but by the time it began advertising Biocel Cream in 1958 it had relocated to Chertsey, Surrey. Both of these addresses for Chase have connections to Tokalon.

Poudre Tokalon

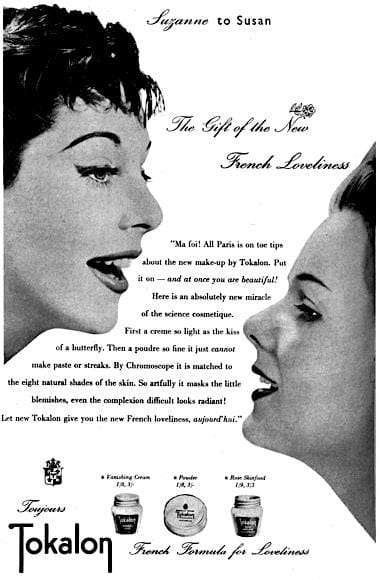

Tokalon face powder advertisements in Britain and France only refer to Poudre Fascination after the war. In France, it came in seven shades which were said to have been selected using a Chromoscope, an idea Tokalon had first used just before the war. The British shade range was also advertised as selected using a Chromoscope but appears to have been more limited – Rose Peach, Rachel, Peach, Brunette, and Natural, with Suntan added in 1946.

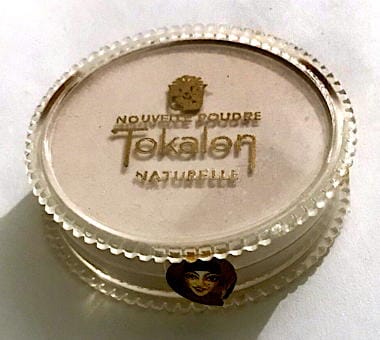

Poudre Fascination was sold in different boxes in Britain and France. The British remained with the older square powder box while the French continued to use the more modern-looking round box they had first used in the 1930s. Both countries would switch to the plastic ‘crystal’ boxes by 1954.

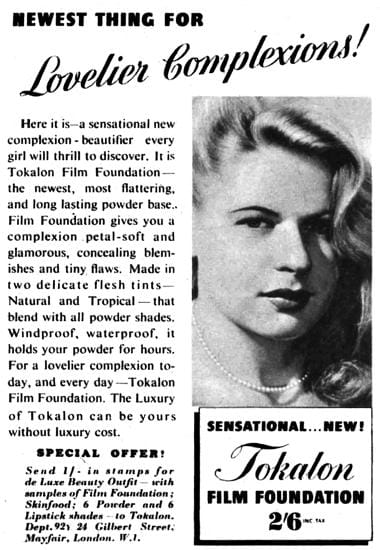

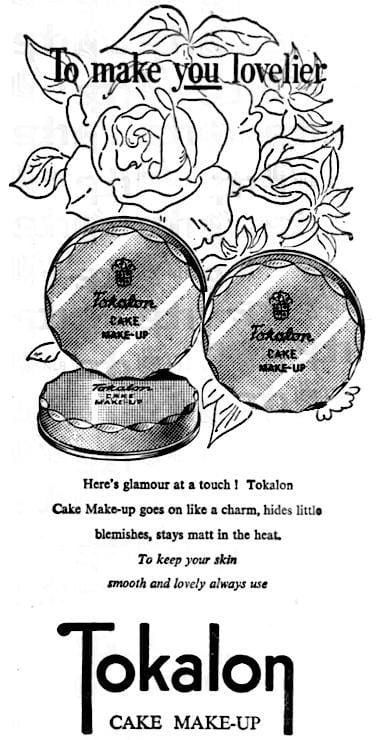

British Tokalon also added two new forms of make-up to its range after the war that I have been unable to locate in France – Tokalon Cake Make-up, which was available by 1948, and Tokalon Film Foundation which arrive in 1950.

Like Max Factor’s Pancake (1938), Tokalon Cake Make-up came in a plastic case. It could be applied with a wet sponge like Pancake but could also be used dry like a powder compact.

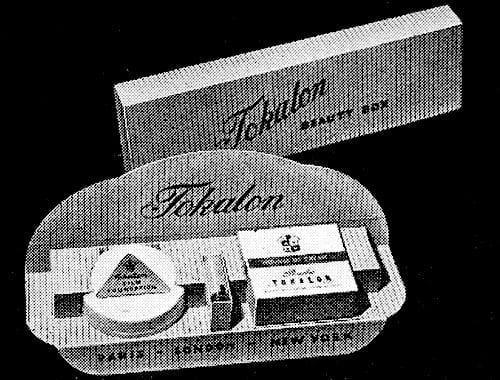

Above: 1950 Tokalon Beauty Box containing Tokalon Film Foundation, Tokalon Lipstick and Poudre Tokalon (UK).

Tokalon Film Foundation appears to be the first tinted foundation introduced by Tokalon into Britain. Information on its composition is missing but it appears to have been a type of powder cream similar to others that became popular after the war. It only came in three shades.

Cake Make-up: “[Q]uickly and easily applied to conceal those tiny skin blemishes and give you a smooth, soft complexion that stays that way for hours and hours.” Shades: Natural, and Peach.

Film Foundation: ‘It protects your skin, conceals

tiny flaws and holds your powder for hours.” Shades: Peach, Natural, and Tropical.

In 1952, Tokalon, Ltd. improved the formula for Poudre Tokalon and housed it in the new crystal powder box mentioned previously. It came in eight shades, again selected using a Chromoscope – Rachel, Natural, Peach, Bridal Rose, Brunette, Rose Peach, Suntan and Rose Natural – with a ninth shade Mirabelle added in 1955.

There appear to have been similar powder developments in France but the crystal/crystale powder box does not appear to have been adopted there until 1954. It came in two nearly identical forms. The first labelled Poudre Tokalon Fascination was sealed with a Tokalon crest. The second labelled Poudre Tokalon had a Pierrot seal which, I assume, mans that it contained Poudre Petalia. Unfortunately, I do not have complete shade ranges for these French powders. The only known French shades are Naturelle, Rose Ocre, Rose Doré and Chair.

Other cosmetics

In 1952, British Tokalon added a smaller lipstic in a pink plastic case in Cherry, Clover, Holly Berry, Ruby, Royal Red, and Petal Pink shades with Flame, with Mirabelle (1955) added later.

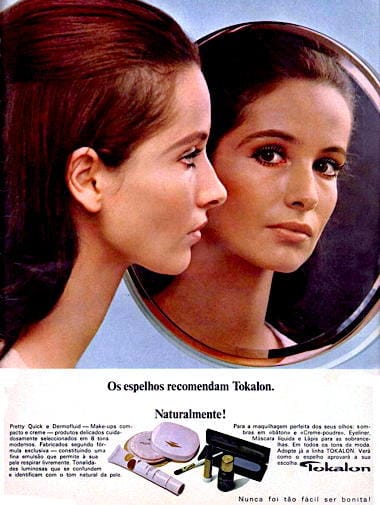

The only other development that I know of was the formation of the Pretty Quick line which was aimed at a younger market than Tokalon. The earliest records I have for it are in Britain but its products also appeared in European countries and places such as Türkiye (Turkey).

Above: 1958 Tokalon Pretty Quick window display.

In Britain, Pretty Quick was produced by the Pretty Cosmetic Co., Ltd., founded in 1958, even though it was a Tokalon range. The company directors of Pretty Quick were also directors of Tokalon and included Auguste E. Baumeister and, by 1964, Tokalon, Ltd. had taken up the distribution of Pretty Quick along with products from Chase and Tokalon.

Later developments

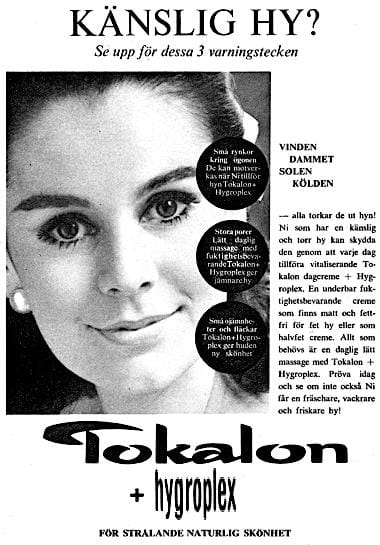

There was a good deal of rationalisation during the 1960s. A number of markets were abandoned and Tokalon became largely a European line. Its skin-care range had a strong French influence with a preference for biologicals which replaced the old Biocel.

Above: 1963 Tokalon Pacenta + Vitamin Crème.

In 1972, OREC S.A. was bought by Cooper Laboratories (Conroy, 2014, p. 379) and it became part of Cooper Cosmetics S.A., a subsidiary that have been founded as early as 1968. In 1992, Cooper cosmetics was bought by the Cooper Development Company, which had once been a subsidiary of Cooper Cosmetics. According to Conroy, Cooper Cosmetics S.A. was sold to a group of investors in 1997 led by Ernst Buchert (Conroy, 2014, p. 380) who was the sole director and administrator of Cooper Cosmetics at the time.

The company continues to operate in Geneva, Switzerland. Its product list includes Tokalon, which is promoted as a Swiss line, and Aseptine, a product range that has developed from the original Cire Aseptine introduced by To-Kalon back in 1912.

Timeline

| 1930 | New French factory opened in the Bois de Boulogne. New Products: Crème Tokalon Biocel Skinfood (UK and France). |

| 1931 | Tokalon, Ltd. moves to 71 Chase Road, London. |

| 1932 | Tokalon Industries, Ltd. established in Canada. New Products: Poudre PerO (France). |

| 1933 | Tokalon (Irish Free State), Ltd. founded. |

| 1935 | New Products: Poudre Fascination Double Mousse of/de Crème (UK and France). |

| 1936 | New Products: Neal’s Perles de Beauté (France); and Love Lipsticks/Crayons-lèvres d’Amour (UK and France). |

| 1937 | Tokalon (Australia), Pty. Ltd. founded in Sydney. |

| 1941 | New British factory opened in South Street, Reading. New Products: Super Crème Tokalon (France). |

| 1947 | Office pour la Recherche et Étude Cosmétique (OREC) S.A. founded in Geneva, Switzerland. |

| 1949 | Tokalon, Ltd. moves from 356 Oxford Street to 24 Gilbert Street, Mayfair. |

| 1950 | New Products: Film Foundation (UK). |

| 1958 | Pretty Chemical Co., Ltd. founded in Chertsey, Surrey. |

| 1972 | Cooper Laboratories International buys OREC S.A. |

| 1973 | OREC S.A. becomes Cooper Cosmetics S.A. Cooper Cosmetics S.A. bought by a group of private investors. |

First Posted: 26th January 2025

Last Update: 3rd March 2025

Sources

The chemist and druggist. (1859-) London: Morgan Brothers.

Conroy, M. S. (2007). The cosmetics baron you’ve never heard of: E. Virgil Neal and Tokalon. Englewood, CO: Altus History.

Conroy, M. S. (2014). The cosmetics baron you’ve never heard of: E. Virgil Neal and Tokalon (3rd ed.). Englewood, CO: Altus History.

Ewing Virgil Neal [1868-1949].

1933 Tokalon Skin Food (UK).

1933 Women filling powder boxes in the Tokalon factory (UK).

1933 Poudre PerO (France).

1933 Tokalon Lady’s Head Compact (UK).

1933 Poudre Tokalon (UK). Tokalon was advertising that its Poudre Fascination had a dull finish well before it introduced its the Double Mousse of Crème version.

1935 Poudre Fascination Double Mousse de Crème au fini mat (matt finish) (France).

1935 Poudre Tokalon Double Mousse de Crème (France).

1936 Tokalon Crayon-Lèvres d’Amour (france.

)

1937 Tokalon products (Australia).

1937 Neal’s Perles of Beauté (France).

1937 Trade advertisment for Tokalon Lipstick (UK).

1938 Poudre Tokalon (UK). An advertisment copied from Lady Esther in the United States.

1938 Tokalon Sports Cream (UK).

1939 Crèmes Tokalon (France).

1939 Tokalon Biocel Skin Food (UK).

1939 Poudre Tokalon (UK).

1942 Tokalon Super-Crème (France).

1942 Tokalon Rose Skinfood with Biocel (UK).

1950 Tokalon Film Foundation (UK).

1954 Crème Tokalon Blanche, Rose, and Grasse in tubes along with Poudre Tokalon Fascination in a new crystale container (France).

Crystal/crystale (plastic) powder box. The Pierrot seal suggest that it contains Poudre Petalia.

1954 Tokalon Vanishing Cream, Powder, and Rose Skinfood (UK).

1954 Tokalon Cake Make-up (Singapore).

1954 Creme Tokalon (Germany).

1958 Chase Laboratories Biocel Cream (UK).

1961 Drawing of a counter display for Pretty Quick cosmetics (UK).

1965 Tokalon Hygroplex (Sweden).

1972 Tokalon (Portugal).