Automatic Mascara

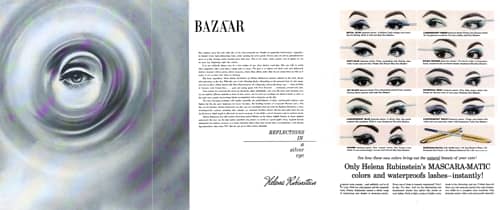

In 1957, Helena Rubinstein introduced her Mascara-Matic, a cream mascara in a dramatically new applicator. Rubinstein called it an automatic mascara because the mascara was picked up ‘automatically’ by the applicator. The term was picked up by other cosmetic companies when they released their versions of this product on the market but quickly depreciated in the 1960s. Today, these automatic applicators are simply known as mascaras.

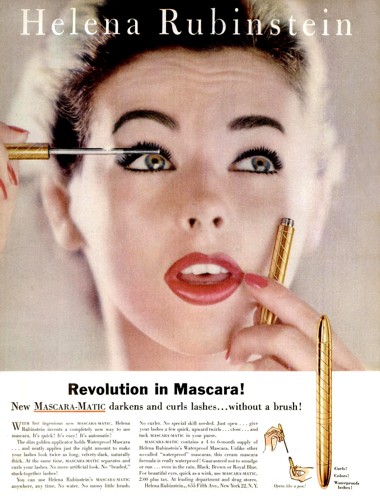

Above: 1960 Helena Rubinstein Mascara-Matic.

Mascara-Matic

The Mascara-Matic combined a reservoir of cream mascara with a grooved applicator built into a screw top cap. As the applicator was withdrawn it was pulled through a central opening that acted both as a seal to reduced evapouration and as a wiper to remove superfluous mascara. The applicator itself was a metal rod with grooves to trap mascara when the rest of the rod was wiped clean.

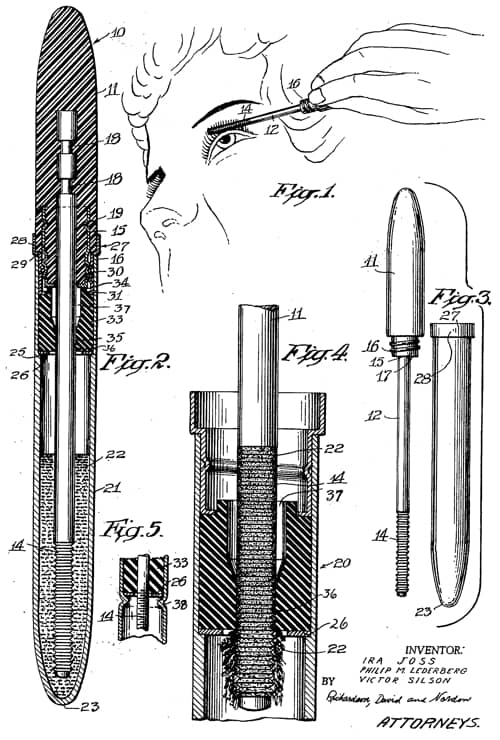

Above: 1962 Drawings from the patent for the automatic applicator invented by Ira Joss, Philip M. Lederberg, and Victor Silson (US Patent: 3,033,213, 1962).

The amount of mascara remaining on the metal rod/wand after it was withdrawn was very important; too little made applying the mascara very tedious; too much and the eyelashes would stick together.

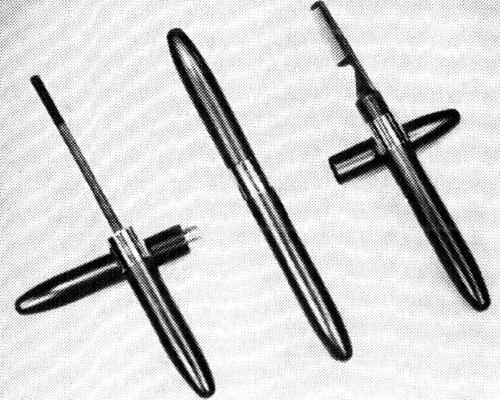

Above: The Mascara-Matic applicator built into the screw top cap.

The mascara formula Rubinstein used in the Mascara-Matic appears to have been the one she used in her earlier Waterproof Mascara based on a licence she obtained from Helene Vierthaler Winterstein [1900-1966]. The use of a volatile solvent reduced the possibility of bacterial contamination – an issue with this type of mascara – but also affected the selection of materials used in the container. Solvent-based mascaras are very prone to evaporation so a good seal was needed to help reduce this. Also, as many plastics are degraded by solvents, or allow solvents to permeate through them, the mascara was stored in an inert glass vial within the metal case.

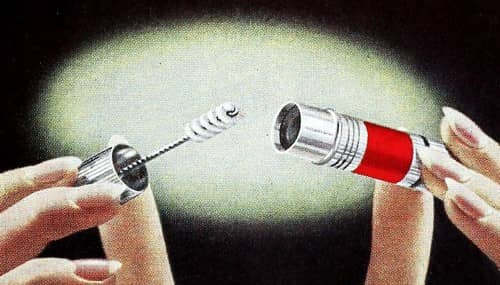

c.1958 Television advertisement for Rubinstein’s Mascara-Matic

See also: Liquid and Cream Mascara

Rubinstein’s Mascara-Matic applicator was covered by patent (U.S. patent No. 3,033,213) but its design owed much to an earlier patent developed by Oscar and Egon Wurmböck of Munich, Germany (U.S. patent No. 3,363,635) which had been acquired by Rubinstein. Fortunately for Rubinstein an earlier patent taken out by Frank L. Engel Jr. in 1939 (U.S. patent No. 2,148,736), had long since expired.

It should also be noted that the Mascara-Matic was not the first cream mascara to use an inbuilt applicator. In 1939, Parfum Ronni, Inc. of New York released a cream mascara into the American market that had a saw-shaped applicator attached to the lid. It appears to have disappeared within a few years. The reason for its disappearance is unknown but America’s entry into the Second World War in December, 1941 may have been a factor.

Above: 1939 Ronni Mascara Applicator. The small comb attached to the cap was replaced in the tube after use.

Brush applicators

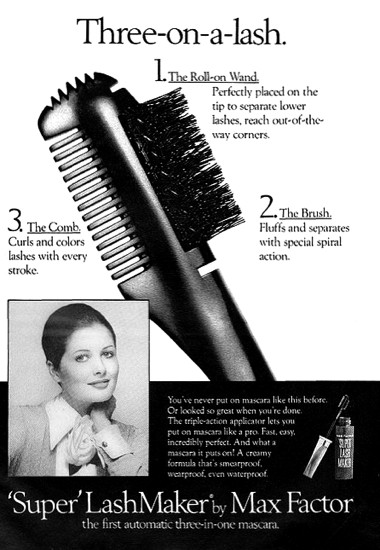

One of the selling points Rubinstein used for the Mascara-Matic was that it was brushless. However, the grooved metal applicators/wands were far from satisfactory. The Scoville Manufacturing Company came up with a compromise of rod and comb; the rod applied the mascara while the comb spread the lashes.

Above: 1958 Scoville mascara container. This model appears to have been used by Aziza in their first Azizamatique.

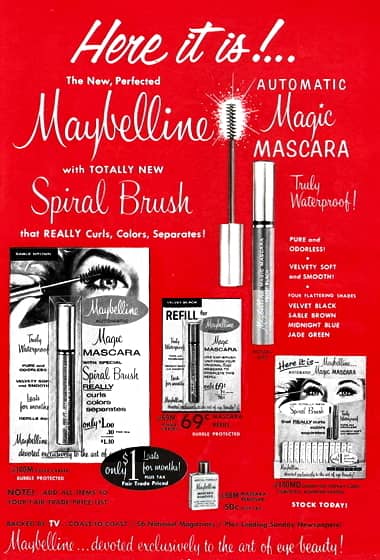

Other applicators were tried but within a few years most automatic mascaras had switched to using a spiral wire brush, the first that I know of being Maybelline’s Magic Mascara introduced in 1958.

Spiral wire brush applicators contained bristles, typically made of a synthetic material like nylon inserted between bent wire that was twisted around to make the brush. These had been used to apply mascara before, most notably by National Cosmetics in its Modern Mascara released in 1937. This used a spiral wire brush to lift and apply mascara from a hollow, cylindrical, cake mascara; not a cream formulation as found in the later automatic forms.

Above: 1938 Modern Mascara. The brush was dampened before it was inserted into the hole in the round cake. This must have created some potential for bacterial growth in the tube over time.

See also: Cake Mascara

The shape of the brush, the bristle shape and the bristle count were important to the functioning of the mascara. For example, brushes with higher bristle counts tended to pick up more mascara, resulting in a thicker application, while those with lower bristle counts were better at separating the lashes. A large number of different shapes were developed including: straight, curved, spiral, tapered and spherical. This range increased dramatically when technical advancements in moulded plastics enabled manufacturers to develop highly engineered brushes. Current automatic mascara wands come in a wide variety of shapes, sizes and colours with brush fibres that vary in hardness, length and shape.

Above: Assorted mascara brushes. The wand brush has became an important selling point for many mascaras.

Developments in formulation

As in the past, formulations used in automatic mascaras can be loosely divided between those that are waterproof and those that are water-resistant. Water-resistant mascaras are typically water-based emulsions. These deliver a substantial film to the lashes that lasts throughout the day, while still being relatively easy to remove with soap and warm water. Longer-lasting mascaras are generally made as anhydrous waterproof formulations using hydrocarbon solvents and anhydrous raw materials. As they contain no water these mascaras are very durable and resist tears, perspiration and smearing, but are more difficult to remove and potentially more irritating to the eyes. It is also possible to create intermediate forms between these two extremes by combining hydrocarbon solvents with emulsions.

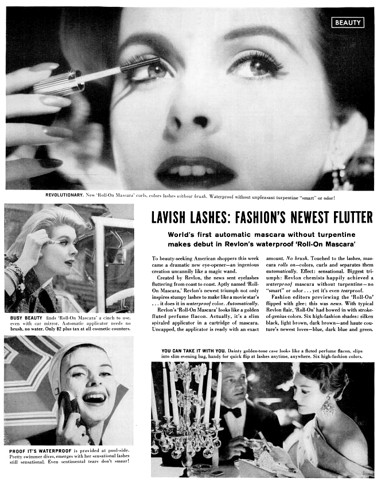

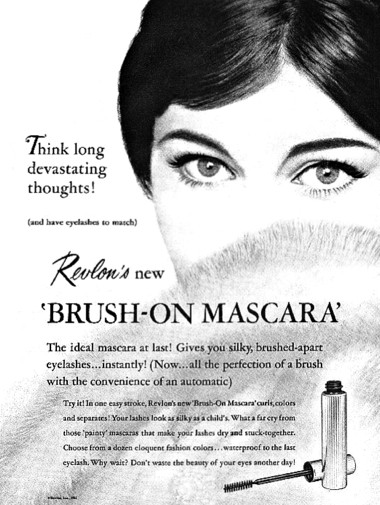

Rubinstein’s Mascara-matic was made using turpentine as the solvent so was waterproof. The first automatic mascara made without turpentine appears to have been Revlon’s Brush-On Mascara released in 1958.

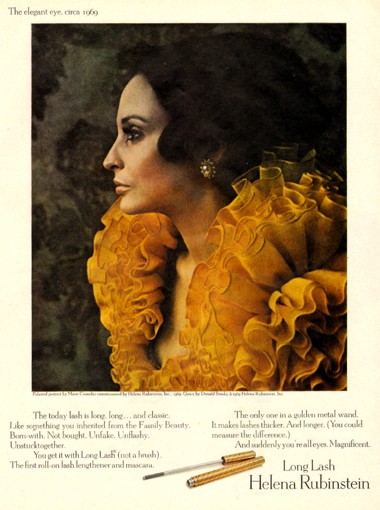

The creamy nature of automatic mascara made it easy to introduce a wide range of additives into the formulations. An early example of this was the inclusion of fibres in lash-lengthening mascaras. The first that I know of were Helena Rubinstein’s Long Lash Mascara and Revlon’ Fabulash Mascara, both introduced in 1963. When applied, the fibres extended beyond the natural ends of the eyelashes thereby lengthening them. A downside was that they could be very irritating if they came in contact with the eyes.

(parts by weight) Beeswax 27.00 Ozokerite 75/78°C 4.00 Stearic acid XXX 2.00 Preservative 0.25 Inorganic pigments 7.00 Triethanolamine 0.70 Aluminium stearate 2.50 Rayon fibers 5.00 Hydrocarbon solvent (38-48°C) q.s. 100 (deNavarre, 1975, p. 715)

Later developments included the addition of hollow particles to create a thicker film, synthetic or natural polymers to induce a curling effect on the lashes, waterproofing topcoats, lash primers and the use of brightly coloured and pearlescent materials (Draelos, 2010, p. 192).

First Posted: 19th January 2018

Last Update: 5th January 2020

Sources

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston: D. Van Nostrand Company.

deNavarre, M. G. (1962-75). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd ed., Vols. I-IV). Orlando: Continental Press.

Draelos, Z. D. (Ed.). (2010). Cosmetic dermatology: Products and procedures. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Harry, R. G. (1944). Modern cosmeticology (2nd ed.). London: Leonard Hill.

Jannaway, S. P. (1936). Eye cosmetics. The Perfumery and Essential Oil Record. November, 438-440).

Riley, P. (2000). Decorative cosmetics. In H. Butler (Ed.), Poucher’s perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (10th ed., pp. 167-216). Great Britain: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Wetterhan, J., & Slade, M. (1957). Eye makeup. In E. Sagarin (Ed.), Cosmetics: Science and technology (pp. 286-295). New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc.

Woodhead, L. (2003). War paint. Miss Elizabeth Arden and madame Helena Rubinstein their lives, their times, their rivalry. London: Virago Press.

1957 Helena Rubinstein Mascara-Matic.

1960 Part of an advertisement for Helena Rubinstein Mascara-Matic.

1958 Revlon Roll-On Mascara, the company’s first automatic mascara and the first automatic to be made without turpentine.

1959 Industry advertisement for Maybelline Magic Mascara. Released in 1958, it was the first automatic mascara that used a spiral wire brush.

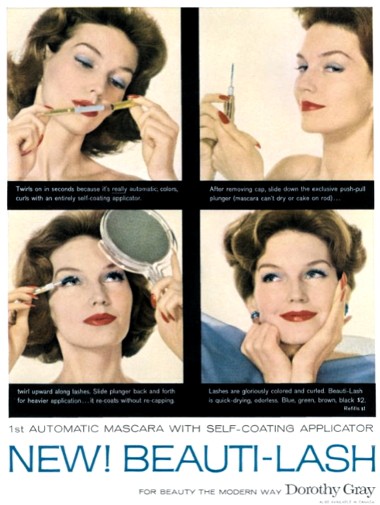

1959 Dorothy Gray Beauti-Lash Automatic Mascara.

1959 Azizamatique Mascara in 10 shades using a Scoville designed applicator. An Azizamatique Brush-on Mascara was released in 1962.

1961 Revlon Brush-On Mascara now using a brush applicator.

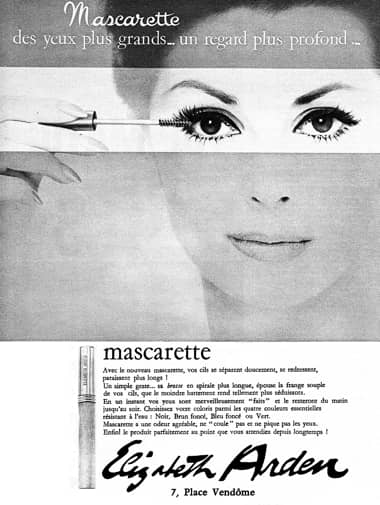

1962 Elizabeth Arden Mascarette. Introduced in 1959, it also used a brush applicator.

1963 Max Factor Lash-Full Mascara that is still using the older, grooved tube applicator.

1969 Helena Rubinstein Long Lash Mascara. It still used the grooved applicator but now had nylon fibres in the mascara to help lengthen the lashes.

1975 Max Factor Super LashMaker Mascara with an applicator that includes a comb, brush, and roll-on wand.

1976 Maybelline Comb-on Mascara.