Liquid and Cream Mascara

The use and status of mascara increased steadily through the twentieth century with cake mascara as the most popular form. It was still being made in the 1950s in much the same way as it had been in the 1920s, when triethanolamine stearate and other less alkaline soaps were introduced into the formulation.

See also: Cake Mascara

The packaging design had an even longer pedigree, with the product still being sold in containers that looked very similar to the water cosmetique/mascaro boxes of the late nineteenth century.

See also: Water Cosmetique (Mascaro)

Although popular, cake mascara suffered from two major drawbacks: it required wetting before the mascara could be lifted from the cake and applied, but water was not always readily available; and although some forms of cake mascara were water-resistant they were not waterproof, which meant that the mascara was affected by tears and perspiration. These issues led some women to prefer using either a liquid or cream mascara instead.

Liquid mascara

Liquid mascaras could be produced by adding colour to a dilute gum mucilage made from gum tragacanth, quince seed or some other mucin, with more modern forms produced using a synthetic hydrocolloid like hydroxyethylcellulose.

The water-soluble gum served as a film former, suspending and spreading the pigments as well as helping stick it to the lashes, while the more volatile alcohol reduced the time it took to dry. Cheaper versions could leave out the alcohol but this increased the time the mascara took to set.

per cent. Gum tragacanth 0.2 Alcohol 8.0 Water 83.8 Lampblack 8.0 Preservative q.s. (Harry, 1944, p. 112)

Liquid mascaras did not need water to be applied like cake mascara but they were also affected by tears and perspiration. They also tended to stick the lashes together and became brittle when dry, with a propensity to flake.

Liquid mascaras were also made by suspending powdered black or other pigments in an alcoholic solution of a resin, such as rosin (colophon) or benzoin, to produce a kind of lacquer on the lashes. Turpentine or industrial methylated spirits could be used as the solvent as could isopropyl alcohol or the more expensive ethyl alcohol.

Oz. Rosin tincture (10%) 21.5 Shellac 1.5 Castor oil 2.0 Lampblack 15.0 Industrial spirit (toilet quality) 60.0 (Jannaway, 1936, p. 438)

These liquid mascara dried relatively quickly and, more importantly, were waterproof – which made them more attractive than cake mascara for some people. However, they stung quite badly if the mixture got into the eyes. Their volatile nature meant that they were generally packaged in small glass bottles with a screw-top lid – needed to reduce evaporation – to which a brush applicator was attached.

Above: Maybelline liquid mascara in a screw top bottle.

Cream mascara

Adding colour to a typical ‘eyelash grower’ would make a primitive cream mascara. Made with a base of lanolin or petroleum jelly, further thickened with waxes like beeswax or ceresin, produced a preparation similar to a cream rouge but coloured with black and brown pigments rather than reds.

Oz. Bone black (fine) 40 Ceresin 5 White beeswax 5 Lanolin 10 Petroleum jelly 40 (Jannaway, 1936, p. 439)

See also: Eyelash Growers

As they were not susceptible to evaporation they were generally sold in small pots.

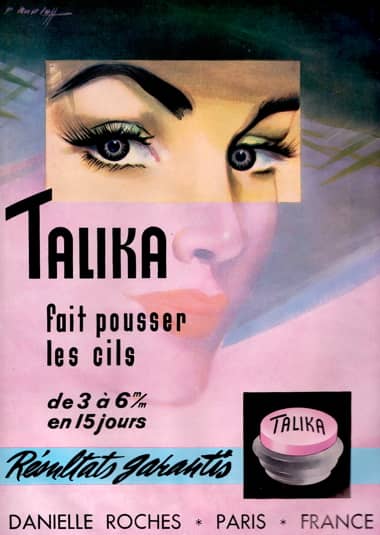

Above: 1954 A pot of Danielle Roche Talika Mascara.

Being made exclusively from oils and waxes, these anhydrous mascaras were waterproof. However they were greasy, not smear-proof and took a long time to dry out. If the drying time was reduced by adding a volatile solvent, this increased their potential as an eye irritant.

A better cream mascara could be produced by making an emulsion. A simple method was to take a lanolin absorption base, mill lampblack into it and then add water until the desired consistency was reached. A second method was to simply mix pigment into an oil-in-water emulsion such as a vanishing cream.

Pigment 10 parts Beeswax 9 parts Carnauba wax 2.25 parts Triethanolamine 3.5 parts Stearic Acid XXX 8.0 parts Water 67.25 parts (deNavarre, 1941, p. 373)

Cream mascaras could also be made as an emulsion using a formula normally used to make a cake mascara but adding water so that it formed a cream. The presence of water had other useful effects. It was absorbed into the lashes which increased their diameter making the lashes look larger and, on occasion, it also caused them to curl.

As with emulsion-based cake mascaras, these oil-in-water emulsions commonly used soaps like triethanolamine stearate or oleate, diglycol stearate and glyceryl monostearate as emulsifiers. Waxes were included to improve adherence of the film to the hair, increase water-resistance, and add body and gloss; oils were mixed in to reduce flaking; and water-soluble gums were added to help suspend the pigments, act as film formers, and reduce smearing of the pigments after they were applied. Other ingredients included antioxidants to help stop the unsaturated oils from going rancid, and preservatives to prevent bacteria from growing in the aqueous mixture.

(parts by weight) Oleic acid 4.75 Glyceryl monostearate (pure) 1.25 Beeswax, yellow 9.00 Carnauba wax 6.50 Cellosize (H.V.) 1.50 Pigments 5.0-8.0 Triethanolamine 2.50 Preservatives q.s. Antioxidants q.s. Water q.s. 100 (deNavarre, 1975, p. 714)

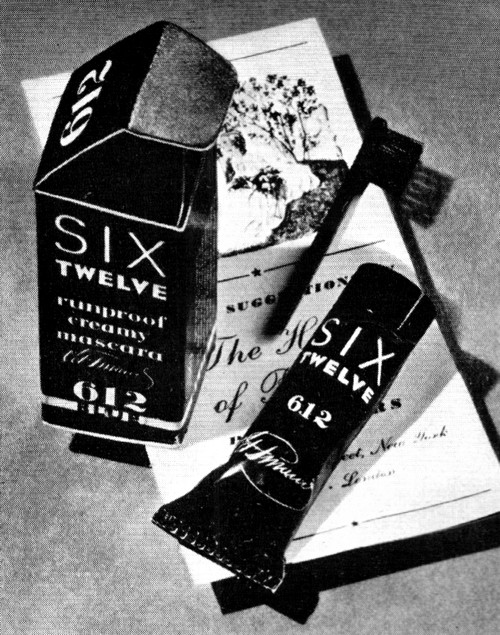

Cream mascaras of this type were generally packaged in tubes to help stop them from drying out with the mixture squeezed out on a mascara brush, like toothpaste on a toothbrush. As a cream they were more viscous and so were easier to apply than liquid forms. Both water-resistant and waterproof forms were made, giving them an appeal second only to cake mascara.

Above: 1935 Pinaud 612 Cream Mascara with applicator. A tube and a brush was the commonest packaging used for cream mascaras.

A formulator could make a cream mascara water-resistant by carefully selecting the ingredients or by using a water-in-oil emulsion rather than the more common oil-in-water form. A completely waterproof cream mascara required excluding the water and the emulsifiers altogether and replacing them with a hydrocarbon solvent. Aluminium stearate could be used to gel the hydrocarbon solvent and add body to the mascara, something that would otherwise require a large amount of wax; while beeswax would add adhesion to the hair; and ozokerite would add substance to the film.

(parts by weight) Pigments 5.0-10.0 Beeswax, yellow 26.00 Ozokerite 75/78°C 4.00 Lanolin 0.50 Preservative 0.25 Aluminium stearate 2.50 Hydrocarbon solvent (38-48°C) q.s. 100 Procedure: The aluminium stearate is added to the solvent with stirring while the mixture is heated to approximately 90°C and maintained at that temperature until solution and gelation are evident. The waxes are melted together and added to the solvent. The pigments are ground in a portion of the solvent-wax mixture and added to the remainder of the batch. Stirring is continued until cool to avoid settling of pigments while the mixture is still warm and fluid.

(deNavarre, 1975, p. 715)

Like liquid waterproof mascaras, solvent-based cream mascaras could irritate the eyes. They were also more difficult to remove than oil-in-water emulsions. Some formulations attempted to overcome this by adding in a small amount of soap such as triethanolamine stearate. However, this came at the cost of making them less than waterproof.

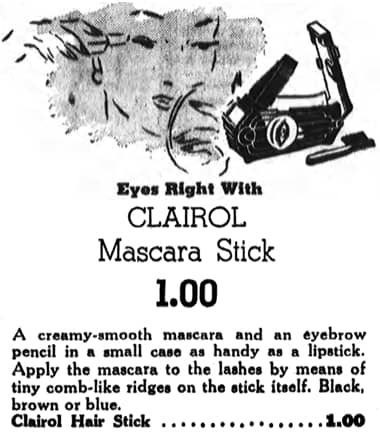

Above: 1941 Clairol Mascara Stick. Although a mascara brush was included in the package, this unusual mascara could be applied without it using the stick which was made with comb-like ridges.

Automatic mascara

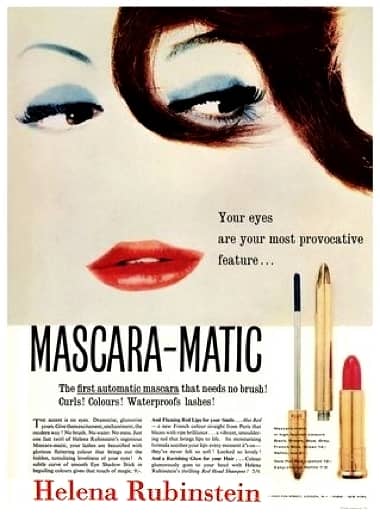

Although cream mascaras enjoyed some success, their domination of the mascara market only came about when a new mascara applicator was introduced in the 1950s. The first product of this type was the Mascara-Matic developed by Helena Rubinstein in 1957. This new applicator revolutionised the mascara market and was widely copied. In its slim, gold case it had an elegance that had only been rarely achieved in cake mascara packaging. So when, in 1958, Maybelline – then the largest manufacturer of mascara in the United States – introduced its automatic applicator, Magic Mascara, this marked the beginning of the end for other types.

Also see: Automatic Mascara

Updated: 20th March 2019

Sources

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston: D. Van Nostrand Company.

deNavarre, M. G. (1962-75). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd ed., Vols. I-IV). Orlando: Continental Press.

Draelos, Z. D. (Ed.). (2010). Cosmetic dermatology: Products and procedures. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Harry, R. G. (1944). Modern cosmeticology (2nd ed.). London: Leonard Hill.

Jannaway, S. P. (1936). Eye cosmetics. The Perfumery and Essential Oil Record. November, 438-440).

Riley, P. (2000). Decorative cosmetics. In H. Butler (Ed.), Poucher’s perfumes, cosmetics and soaps (10th ed., pp. 167-216). Great Britain: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Wetterhan, J., & Slade, M. (1957). Eye makeup. In E. Sagarin (Ed.), Cosmetics: Science and technology (pp. 286-295). New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc.

1919 Curlash Cream.

1920 Eydol cream mascara.

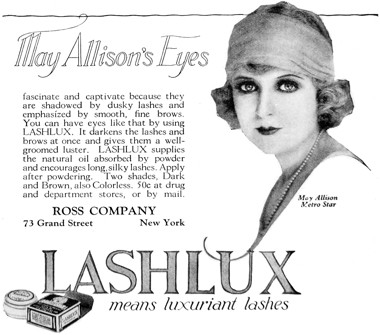

1921 Lashlux cream mascara.

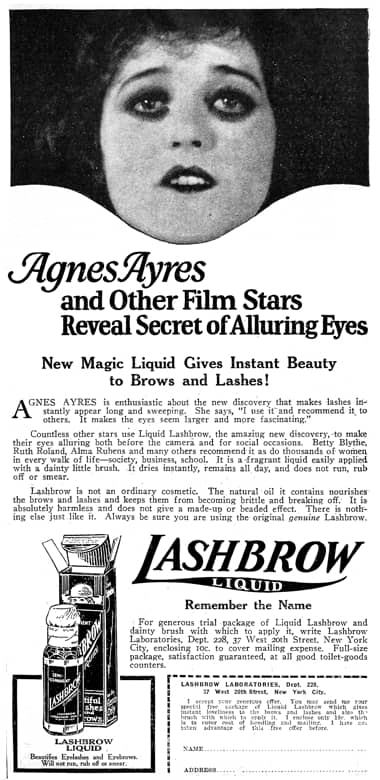

1923 Lashbrow Liquid.

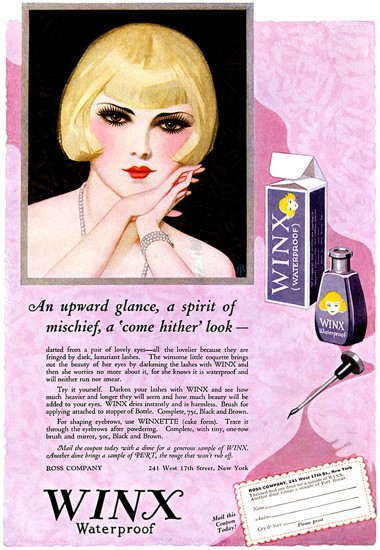

1925 Winx waterproof liquid mascara.

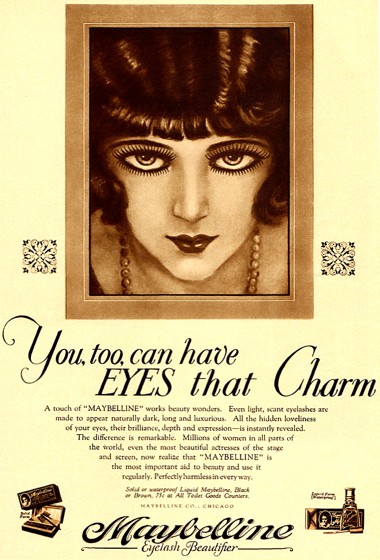

1928 Maybelline cake and liquid mascara.

1937 Tattoo waterproof cream mascara.

1939 Dark-Eyes Mascara that is ‘swimproof’.

1939 Ronni Cream Mascara with an inbuilt applicator.

1940 Camille Cream Mascara.

1944 Clairol Stick Mascara.

1950 Vogue Products Lash-Kote.

1957 Helena Rubinstein Waterproof Mascara.

1957 Talika cream mascara.

1959 Helena Rubinstein Mascara-Matic.