Cake Mascara

Until the 1960s, the most popular form of mascara in the twentieth century was the cake or block type. In the nineteenth century it had been known as ‘water cosmetique’ or ‘mascaro’ and it was only after 1900 that its name began to change to the mascara we are familiar with today.

See also: Water Cosmetique (Mascaro)

Like its precursors – water cosmetique and mascaro – cake mascara was normally packed in a small cardboard and/or metal box with a mirror and a tiny brush that looked like a moustache brush or small tooth brush.

Above: Best Super Mascara in a cardboard container with a block of cake mascara, a mirror and a small brush. This type of packaging was modeled on French water cosmetiques/mascaros of the nineteenth century.

Early cake mascaras

Water cosmetiques, mascaros and early cake mascaras were all made the same way, by mixing black or brown pigments into sodium stearate soap chips. These early mascaras were basically a black soap so it is not surprising that after milling, the mixture was extruded from a plodder into strips which were then cut to length, a process also used to make cakes of soap.

Carbon black 50% Coconut oil sodium soap 25% Palm oil sodium soap 25% Procedure: Carefully sift the pigment and combine with the soap chips; pass the mixture several times through a mill and then through a plodder; finally press into cakes.

(Wetterhahn & Slade, 1957, p. 292)

The product was cheap to make and was generally sold at outlets catering to the lower end of the cosmetic market. This reflected the status of mascara which did not achieve the stature given to lipstick until after the Second World War.

Using cake mascara

To apply the mascara, a wet brush was scrubbed across the cake to pick up the colour, which was then brushed onto the lashes. Unfortunately, water was not always available so many women used saliva instead – either by putting the brush into their mouth or by spitting directly onto the cake – giving this cosmetic the dubious name of ‘spit black’.

The cosmetic is applied by means of a small brush which is previously moistened. (Licking the brush, a habit into which we fear some ladies have fallen, is not to be commended—soap does not taste nice, nor do tongues with blackened ends look pretty!)

(Redgrove & Foan, 1930, pp. 72-73)

Applying the mascara required a little effort to achieve a good result but with practice a reasonable outcome could be achieved. Skillful use of the brush could add curl to the lashes adding to the pleasing effect. Women who wanted an extra curl could used an eyelash curler such as the one produced by Kurlash.

See also: Kurlash

[A] special cosmetic is prepared and is applied to the lashes with a tiny brush. The little bar of cosmetic is moistened, and the lashes are then brushed with an upward and outward movement from the roots. The upward movement induces the “curl,” and the outward movement prevents their sticking together. This operation requires great skill and practice. When first experimented with, traces are apt to find their way into the eye with painful results.

(Poucher, 1926, p. 58)

Companies usually included instructions in the box. These ranged from the very brief to more the detailed, as with those shown below:

To Apply Maybelline—Wet brush thoroughly, shake out excess water and rub over Maybelline until edge of brush is well covered. Tilt head back and apply to upper lashes, stroking from base to tips. Hold brush against lashes for a second to make them curl. If Maybelline on lower lashes is becoming to you apply with a down or cross-wise stroke of the brush with the head tilted forward. When Maybelline has set on the lashes, brush them gently with a soft dry brush for a soft natural effect.

Keep Brush Clean—Rinse in warm water when through.

To Remove Maybelline—Close eyes tightly and wash gently with soap and warm water, finishing with cold rinse, or any good cleansing or face cream will remove Maybelline.(Maybelline instruction booklet, n.d.)

Eyebrows

Like water cosmetique/mascaro before it, mascara was also used by women to colour their eyebrows – a practice that lasted at least until the Second World War, after which eyebrow pencils became the norm.

Improvements

Although early cake mascaras were serviceable they had a number of problems. The sodium soaps used to make them were very alkaline, which meant that the mascara stung if it got in the eyes; they were inclined to flake off the eyelashes; and, being made almost entirely from soap, they would smudge when wet.

The first improvement to the basic formula occurred in the nineteenth century, when a little acacia or tragacanth gum was added to help the cosmetic adhere to the lashes. Then, in the 1920s, the sodium stearate was replaced with less alkaline soaps, like triethanolamine stearate or oleate, diglycol stearate and glyceryl monostearate; with triethanolamine proving the most popular with formulators. These ‘soap substitutes’ made the mascara less likely to sting when it got into the eyes. When mascaras using them were first introduced they were often advertised with the line “contains no soap” which, although not strictly correct, signaled to the consumer that they were less likely to smart.

Other improvements included the addition of oils and fats – such as mineral oil, castor oil or lanolin – to help reduce the problem of flaking, and the inclusion of waxes – such as hard paraffin, carnauba, ceresin and beeswax – to make the mascara more water-resistant, improve adherence of the mascara to the hair and give added gloss. The added wax also enabled the mascara to be made in specialist moulds rather than by the earlier extrusion method.

Triethanolamine stearate 30 parts Paraffin wax (high m.-p.) 40 parts Beeswax 12 parts Lanolin 8 parts Lampblack 10 parts The method is to melt, mix and mill the ingredients—and afterwards cast or extrude them in stick or tablet form.

This gives the usual black type of mascara. Where a dark brown mascara is desired, the following formula will serve. The triethanolamine soap being formed in situ:

White beeswax 300 Montan wax 100 Stearic acid 300 Triethanolamine 130 Lampblack 20 Burnt umber 150 Melt the waxes and grind in the color in a warm mill. Stir in the ethanolamine and pour into molds.

(D&CI, 1945, p. 102)

Adding oils and fats to the formulation enabled the triethanolamine stearate to create an oil-in-water emulsion when the cake was scrubbed with the wet brush. After the emulsion containing the colourants and the rest of the materials was applied the eyelashes, the water evaporated while the colour – protected by the other materials in the mixture – remained on the now dry lashes.

Using a good balance of materials was critically important to producing a satisfactory cake mascara and cosmetic chemists of the time engaged in a lot of trial and error in their quest to produce a better result. Increasing the amount of triethanolamine made it easier to create an emulsion, but also made the mascara less water-resistant. Adding more wax created a mascara that was easier to pour into moulds and more water-resistant, but too much impeded the formation of a suitable emulsion and made the mascara brittle and more likely to flake.

Parts by weight Triethanolamine stearate 15-30 Paraffin 57°C 15-30 Yellow beeswax 10 Lanolin 10 Carnauba wax 5-10 Inorganic pigments 10-15 Preservatives q.s. Antioxidants q.s. (Rutkin, 1975, p. 712)

Manufacture

Cake mascara was made in two main ways. The first way was to only use oils, waxes, emulsifier and pigment. The second method was to add a small quantity of water to enable the mass to form an emulsion. Using the second method improved the mixing and pickup of the mascara when the brush was scrubbed across the surface of the cake. However, care had to be taken with the amount of water used as, when the water evaporated the cake would shrink – too much and it could adversely affect the appearance of the final product in the box. Some chemists reduced the shrinkage caused by the water loss by adding a small amount of humectant to the mascara mix (Kempson-Jones, 1947, p. 73).

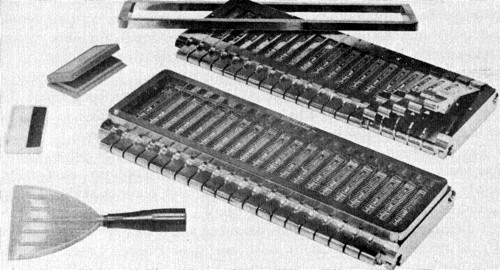

Once the completed formulation was made, the heated mass was poured into moulds which were usually embossed with the name of the manufacturer. The excess mascara was scrapped off and, once cooled, the completed mascara cakes were removed from their moulds, turned over – so the name of the company was on top – and packaged.

Above: Arden ‘Gate’ type cake mascara mould along with scraper to remove the excess mascara and sample mascara box (Rutkin, 1975).

Round cake mascara

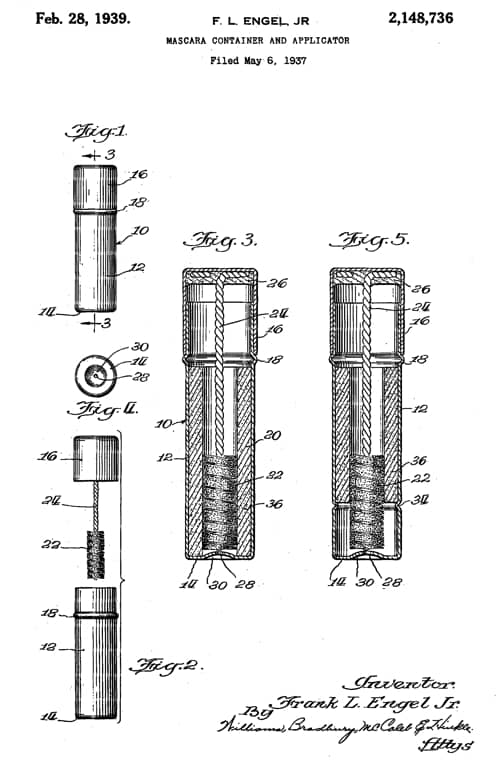

Mention should be made of a rather unusual cake mascara introduced into the United States in 1937 by National Cosmetics, Inc. Called Modern Mascara the cake was made as a hollow cylinder rather than a square block and was sold in a metal tube rather than a box. A wet wire spiral brush was inserted into the hole in the cake and rolled around to collect the mascara which was then applied to the lashes. The manufacturers suggested that the new style brush covered the lashes ‘evenly all over instead of just on their bottom side’. Between uses the brush simply screwed into the case.

Like other cake mascaras the brush had to be dampened to lift the mascara from the block but the brush operated in a similar way to those later used in automatic mascaras, predating them by over twenty years.

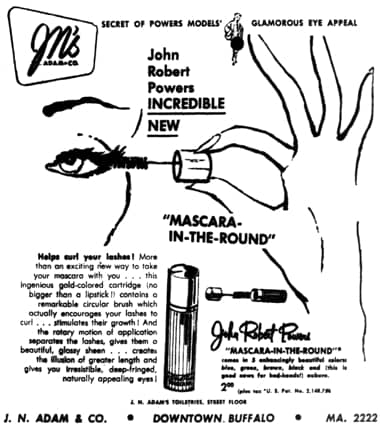

Modern Mascara appears to have been using a patent granted to Frank L. Engel Jr. in 1939 (U.S. Patent No: 2148736). The patent was also used for the John Robert Powers Mascara-In-the-Round from the 1950s.

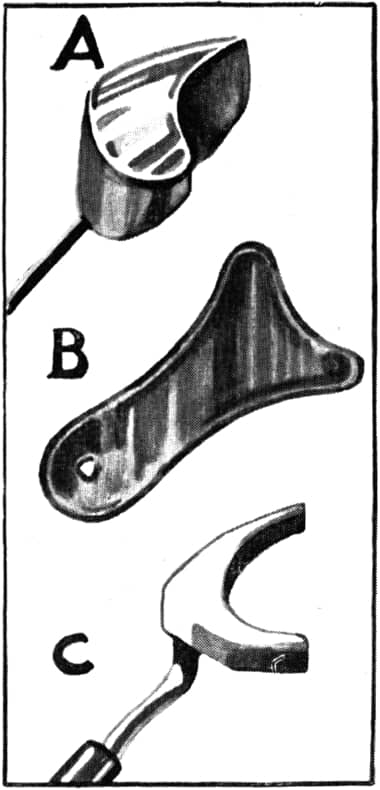

Above: 1939 Drawings from the Frank L. Engel Jr patent for a mascara container and applicator.

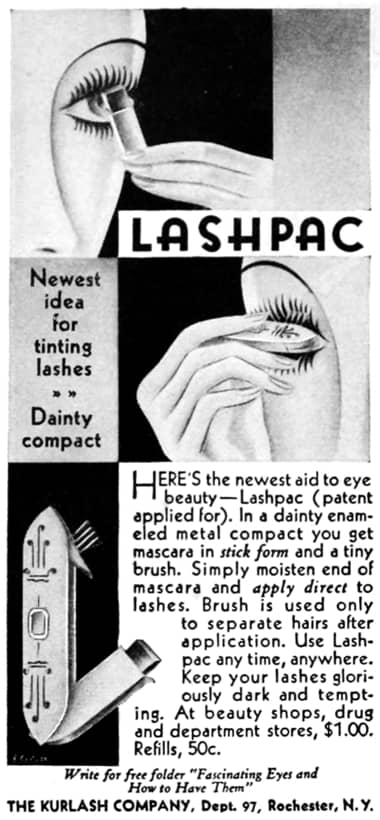

Kurlash

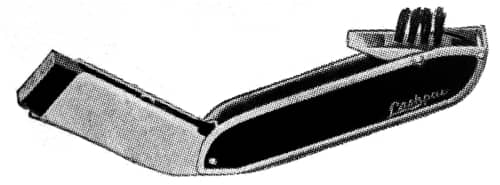

Another small American company responsible for introducing some innovating, cake mascaras was Kurlash. Founded in Rochester, New York State in 1923, their first cake mascara called the Lashpac was applied like a lipstick.

Above: Kurlash Lashpac introduced in 1930.

One end of the Lashpac encloses a stick of mascara, that pushes forward like the usual lipstick. The other end contains a small brush which swings instantly into position for use.

Moisten end of mascara and rub it gently on the upper lashes, always working out toward the ends until desired depth of color is obtained. Then close the compact and, swinging brush out, brush the lashes up to separate and straighten them … The brush is not used to apply Lashpac mascara—only to brush the lashes.(Kurlash, 1936)

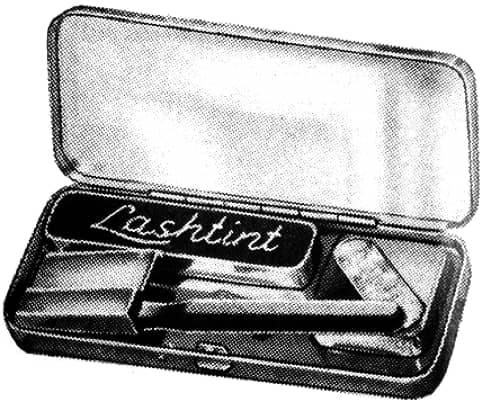

The Lashpac suffered from the same problem as other cake mascaras when it came to finding water. Kurlash tried to rectify this with a second product called the Lashtint Compact, also introduced in the 1930s.

Above: Kurlash Lashtint Compact. The sponge is stored in the small square box in right-hand side of the compact.

The design was roughly similar to a standard cake mascara but included a small sponge in one corner to act as a water source. Kurlash considered this design to be important enough to patent it (U.S. Patent No: 1903681, 1933).

Mascara helpers

When applying cake mascara, a guard or shield could be used to prevent accidentally spotting the area around the eye with mascara. The devices came in a variety of forms and were made from a range of materials including cork, celluloid and tortoiseshell. Numerous patents were taken out for different types. Examples from the United States include: US1850540A, 1930; US1907476A, 1932; US1873928A, 1932; US1974825A, 1934; and US2260614A, 1941.

One way to use an eyelash shield was to place it under the lower lashes, close the eye and then mascara both the upper and lower lashes at the same time. However, a more professional finish was achieved if the upper and lower lashes were treated separately.

Above: 1932 Beautician using a mascara shield when applying mascara to the upper and lower lashes of a client (British Pathé).

Another trick to get a better result was to use two mascara brushes. The first to apply the mascara; the second, clean brush to separate any lashes clumped together by the first.

Automatic mascara

Although liquid and cream mascaras were also made in the first half of the twentieth century and had their adherents, cake mascara was the most common mascara in use. It was not until the arrival of ‘automatic’ mascaras – begun by the introduction of Helena Rubinstein’s ‘Mascara-matic’ in 1957 – that the popularity of cake mascaras came to an end. Cake mascara continued to be made after this – and examples can still be found on the market today – but by the end of the twentieth century ‘spit black’ had been largely forgotten.

See also: Liquid and Cream Mascara and Automatic Mascara

Updated: 8th May 2018

Sources

Daniels, M. H. (1958). Eye beauty. Drug and Cosmetic Industry. 82(4) 442-443, 525.

The drug and cosmetic industry. (1945). 57(1). New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Harry, R. G. (1940). Modern cosmeticology. The principles and practices of modern cosmetics. Brooklyn, NY: Chemical Publishing Company.

Hifer, H. (1945). Mascara. Drug and Cosmetic Industry. 56(1) 617, 42-43.

Kempson-Jones, G. (1947). Mascara: A simply prepared cosmetic. Manufacturing Chemist and Manufacturing Perfumer. 18(2). 73-74.

Poucher, W. A. (1926). Eve’s beauty secrets. London: Chapman & Hall, Ltd.

Redgrove, H. S., & Foan, G. A. (1930). Paint, powder and patches: A handbook of make-up for stage and carnival. London: William Heinemann.

Rutkin, P. R. (1975). Eye make-up. In M. G. deNavarre.The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd ed., Vol. IV). Orlando: Continental Press.

Wells, F. V., & Lubowe, I. I. (1964). Cosmetics and the skin. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation.

Wetterhahn, J., & Slade, M. (1957). Eye makeup. In E. Sagarin. (Ed.). Cosmetics: Science and Technology. New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc.

1930s Wynne Gibson applying cake mascara to her eyelashes.

1930s Norma Shearer applying cake mascara to her eyebrows.

1931 Kurlash Lashpac. This device applied the cake mascara directly to the lashes.

1934 Maybelline cake mascara in a gold metal vanity case introduced in the 1930s.

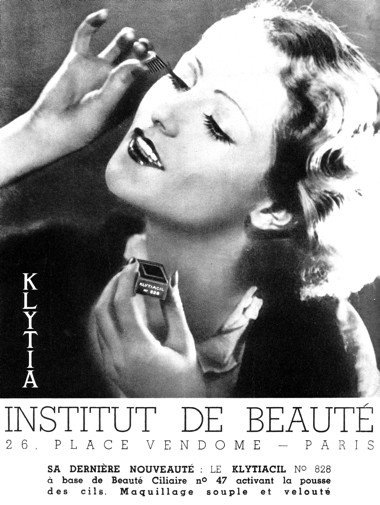

1935 Klytiacil cake mascara.

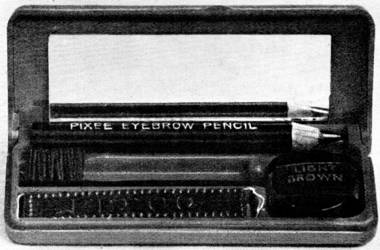

1935 A variant on the usual cake mascara box, this model also included an eyebrow pencil and eyeshadow.

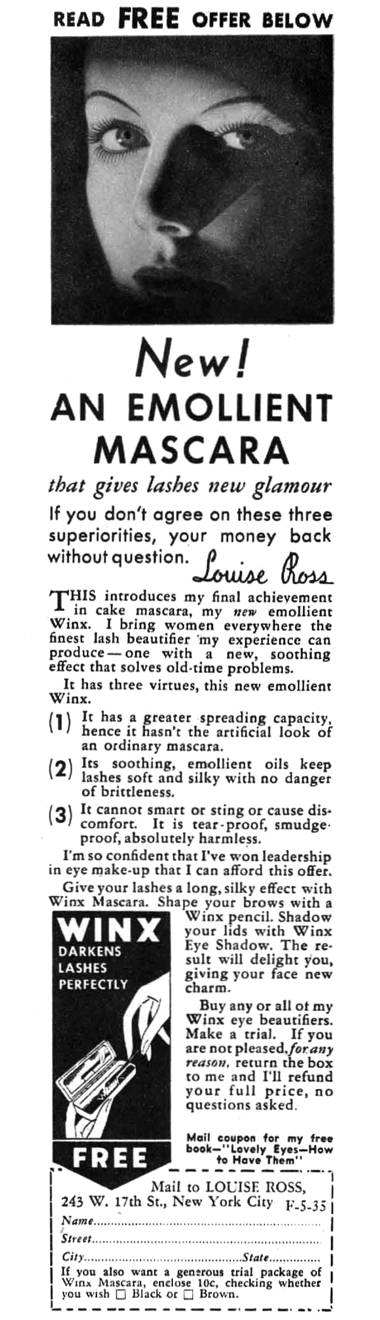

1935 Winx cake mascara made using the emollient method. Winx began making a cake mascara to complement their liquid form to compete with Maybelline.

1937 National Cosmetics Modern Eyes Mascara. The mascara in this device was a cylindrical hollow cake and not a liquid or cream so the brush needed to be dampened before the mascara could be lifted from the block.

Assorted mascara helpers used during the 1930s. A. Made from cork covered with celluloid; B. Cut from a piece of tortoiseshell, celluloid or something similar; C. Professional model for salon or theatrical use.

1939 Ricils.

1946 Aziza cake mascara in a plastic case along with mascara remover and cleansing pads. The use of plastic containers solved the problem of water affecting the packaging.

1947 Rimmel Eyelash Beautifier.

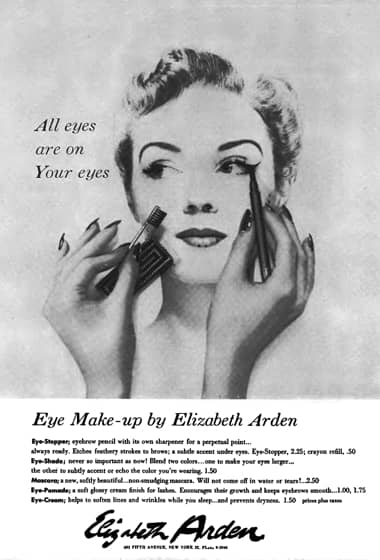

1950 Elizabeth Arden.

1952 John Robert Powers Mascara-In-the-Round.

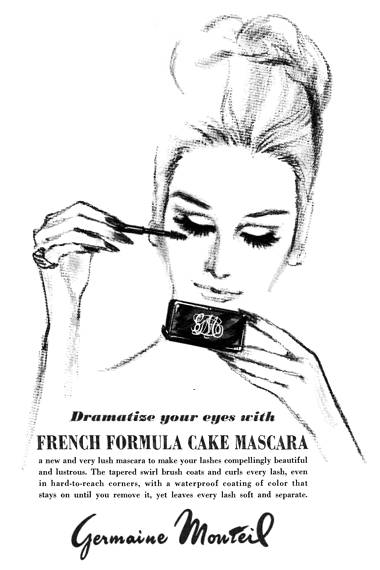

1965 Germaine Monteil French Formula Cake Mascara. The brush used is not typical of earlier cake mascara and has more in common with those used in ‘automatic’ mascaras.

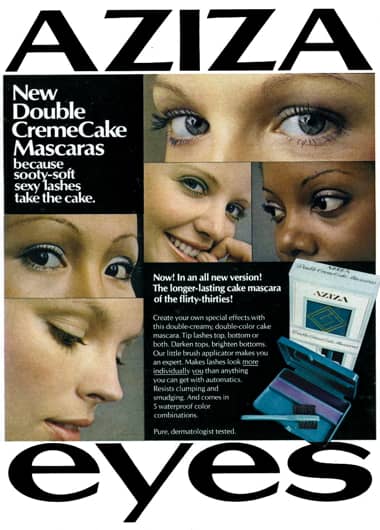

1972 Aziza Double CremeCake Mascara.