Rouge

Early European ideals of health and beauty required women to have a pale, flawless complexions with blushed cheeks and lips, so it is not surprising that rouge has a long history of use. In the nineteenth century, it was so highly regarded that when the use of ‘paints’ was criticised, many writers made an exception for it.

Red and white being the only paints used on the skin, we shall here briefly treat of them. If ever paint were to be proscribed, we should plead for an exception in favor of rouge, which may be rendered extremely innocent, and be applied with such art as to give an expression to the countenance, which it would not have without that auxiliary. White paint is never becoming; rouge, on the contrary, almost always looks well.

(“The toilette of health, beauty, and fashion,” 1834, p. 89)

The raw materials for producing rouge were readily at hand in the nineteenth-century so women could make their own using one of the widely available recipes.

Devoux French rouge is thus prepared: Carmine, half a drachm; oil of almonds, one drachm; French chalk, two ounces. Mix. This makes a dry rouge.

(“The ugly-girl papers,” 1875, pp. 66-67)

However, by the end of that century most women were using rouge manufactured by a cosmetic company.

Reds

Before the advent of modern dyestuffs, the reds used in rouge and other cosmetics were garnered from naturally-occurring animal, vegetable and mineral sources, many of which were also used to colour textiles, paints and foods.

Animal red: The first carmine used in Europe came from Poland. It was made from the dried bodies of a scale insect (Porphyrophora polonica) that was native to Eastern Europe. Following the Spanish conquest of the Americas, Polish carmine was largely replaced by cheaper carmine extracted from the dried bodies of another scale insect (Dactylopius coccus) native to Mexico and Central America.

Cochineal, and the carmine extracted from it, was very expensive to produce and often adulterated. Many nineteenth-century writers issued warnings about this.

The makers of rouge, out of economy, sometimes substitute cinnabar for carmine. You should ascertain if carmine be genuine, which will be the case if it is not altered either by the mixture of salt, of sorrel, or by that of alkali.

(“The duties of a lady’s maid,” 1825, p. 299)

Some also included tests that readers could use to determine if the carmine they purchased was pure.

Vegetable reds: These included cathamine produced from the flowers of safflower (Carthamus tinctoria), alkannin extracted from the roots of alkanet (Alkanna tinctoria), alizarin derived from the roots of the madder (Rubia tinctoria), Brazil wood and red sandalwood. Of these, cathamine appears to have been the most important, its use rivaling that of carmine.

Mineral reds: Two of the commonly used mineral reds – lead tetroxide (red lead, minium, calx of lead) and mercuric sulphide (cinnabar, vermillion) – were poisonous but ferric oxide (iron oxide, ochre) was perfectly safe and is still used in cosmetics today.

The toxicity of red lead and cinnabar was known to nineteenth-century writers and they often advised against using them.

[D]angerous reds are those compounded with red lead, or cinnabar, otherwise called vermilion, produced by sulphur and mercury. Vegetable reds, therefore, should alone be used, since they are attended with little danger, especially if they are used with moderation.

(“The Art of Beauty,” 1825, p.189)

Unfortunately, not all nineteenth-century writers were so careful.

ROUGE is prepared from carmine, and the colouring matter of safflower, by mixing them with finely levigated French chalk or talc, generally with the addition of a few drops of olive or almond oil. … For common purposes, vermilion is used; and it is sometimes prepared for this purpose by mixing it with a few drops of almond oil and of mucilage of tragacanth, placing the mixture in rouge pots, and drying it by a very gentle heat.

(Beasley, 1878, p. 237)

The problem of toxic mineral reds continued, at least in the United States, until the 1920s when they were prohibited by law (deNavarre, 1975, p. 965).

Forms of rouge

Rouge was available in a number of forms in the nineteenth century. Red pigment could be mixed with talc or French chalk to form a powder (rouge en poudre), combined with a fatty/oily material and wax to form a pomade (rouge en pommade), or dissolved in a solvent to produce a rouge infusion (rouge liquide), usually referred to as a bloom although this term was also applied to rouge powders.

Bloom of Roses. (Liquid Rouge.) Carmine, No. 40 2 drachms. Aqua ammonia, FFF ½ ounce. Alcohol, 60° 2 ounces. Gum Arabic ½ ounce. Rose-water, triple 1 pint. Otto of roses 10 drops. Rub the carmine and gum with the aqua ammonia in a porcelain mortar, and a portion of the rose-water, when dissolved add the alcohol slowly and the balance of the rose-water. The perfume to be dissolved in the alcohol. Lastly strain.

(Cristiani, 1877, p. 151)

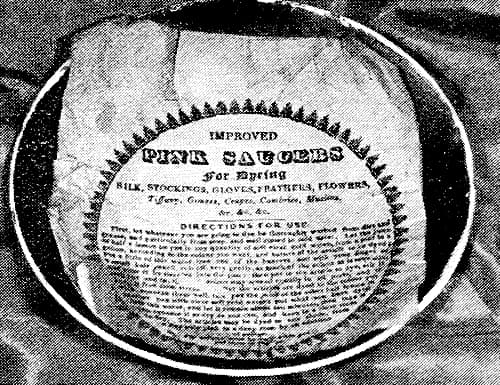

Rouge could be purchased in small pots (rouge en pot), glass bottles, on saucers (rouge en tasse), on paper or foil made up into little booklets (rouge en feuiles), impregnated in fabric (rouge en crépon), or saturated in cotton pads (rouge d’Espagne). Depending on how the rouge was made and the user’s preference, it could be applied with fingers, a camel’s-hair brush, a hare’s foot, a cotton-wool pad, a powder-puff or a piece of fabric.

Above: Pink Saucer (rouge en tasse). These could be used to dye a range of materials in the nineteenth century but the colour, which was released using lemon juice, could also be used as a cosmetic.

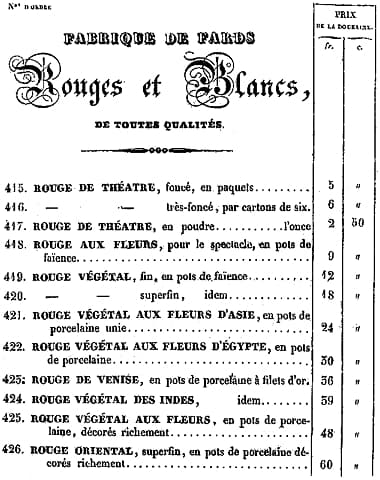

Given the variety of different forms, it is not surprising that nineteenth-century names for rouge varied considerably, recipes for products with identical names differed, and a name was no guarantee against substitution or adulteration. For example, rouge made with cathamine could be referred to as Rouge de Carthame or Rouge Végétal but if it was used to make a rouge for theatrical use, then it could be called Rouge de Théàtre.

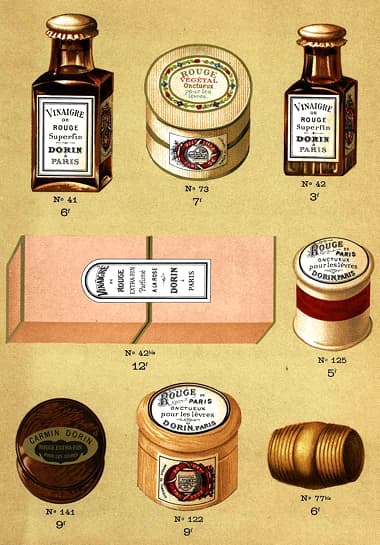

One way to avoid the problem of buying poor quality rouge was to purchase it from a trusted supplier. To help develop trust, sellers of rouge and other cosmetics such as Bourjois, Guerlain and Dorin packaged their wares in quality containers with their name prominently displayed on the containers.

Synthetic reds

The twentieth century saw the inclusion of synthetic reds into rouge formulations – including geranium lake, erythrosine, erythrene and phloxine – which enabled a greater range of red shades to be produced.

Colour: Rose

Carmine, No. 40

CarmoisineColour: Bright red

Geranium lakeColour: Yellowish-red to bluish-red

Eosine

Erythrosine

Erythrene

Phloxine

Phloxine P.

Rose Bengal

Rose Bengal 3B(Modified from Poucher, 1932, p. 544)

As with lipsticks, bromo acids were also added to rouges and could be used to produced a changeable rouge – e.g. Princess Pat English Tint – that worked in the same way as a changeable lipstick – e.g. Tangee Lipstick – that is, it looked orange in the container but turned red on the cheeks.

Also see: Indelible Lipsticks

The use of different synthetic reds changed as the century progressed as synthetic colours became subject to legislative controls. Some early colours did not survive while others were developed, tested and added to approved lists.

Rouge, lipstick and nail polish

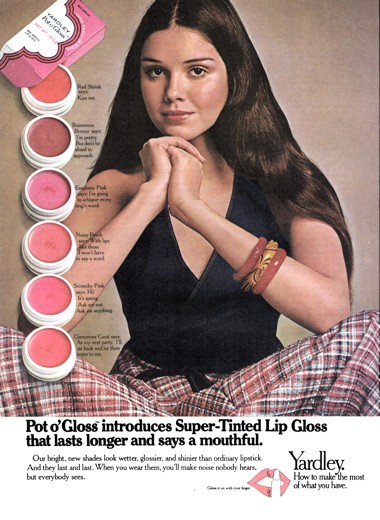

Early forms of rouge were also used to colour the lips. Whether by deliberate design, or through a lack of knowledge on how to use cosmetics, some women used their lipstick as a substitute for rouge in the same way that paste rouge was sometimes used as a substitue for lipstick.

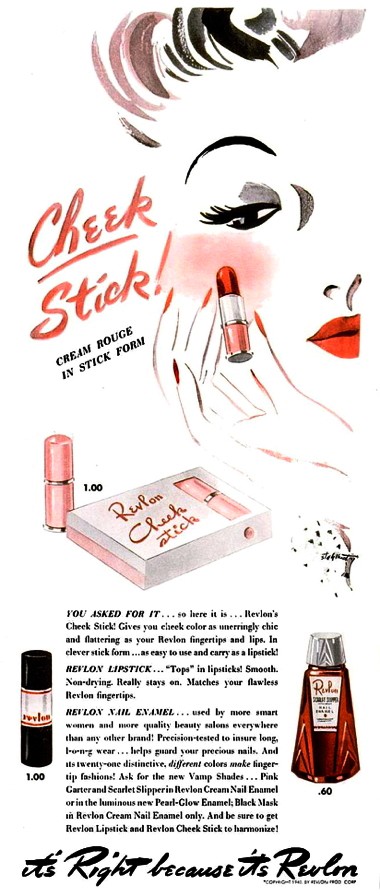

As the use of stick rouge or lipstick increased during the twentieth century it became fashionable for women to match the colour in their rouge with their lipstick. This led to the production of lipsticks and rouges in matching shades.

When the fashion trend of matching lipsticks with nail polish took hold in the 1930s, and the colour ranges of both lipsticks and nail polishes increased dramatically, it was not cost effective for manufacturers to do the same with rouge, and after the Second World War the shade ranges for rouge generally remained more limited than those for lipsticks or nail polishes although they were still colour coordinated with them.

See also: Lipsticks, Nail Polishes and Colour Coordination

Formulations

As the manufacture of rouge reached an industrial scale, the plethora of names used for rouge declined and disappeared. By the early twentieth century, cosmetic chemists were generally referring to different forms of rouge by the base in which the red dyes and pigments were dissolved or suspended – liquid, powder, compact powder, paste and cream – with paste and cream often being conflated even though they were quite distinct in composition.

Liquid rouge

Early liquid rouges were relatively simple solutions of eosin, carmine or some other dyestuff to which a little glycerin was sometimes added to make the product easier to handle.

1 to 3 Carmine, No. 40. 2 to 5 Liquid ammonia, 880. 600 Rose-water. 400 Glycerine. 1008 Dissolve the carmine in the liquid ammonia, add the rose water, and then the glycerine—shake.

Stand aside for one month, and decant the clear liquid.(Poucher, 1932, p. 146)

Early liquid rouges were also made with an alcohol-water base, which enabled the use of alcohol-soluble dyes.

Liquid rouge was used on the cheeks but could also be applied to the lips. If it was designed to be applied to the lips gums were often included to thicken the fluid so that it would stay in place.

For much of the twentieth century liquid rouge was not as popular as compact or cream/paste forms. However, it underwent something of a resurgence after liquid foundations were introduced in the 1940s and 1950s as it could be applied over the liquid foundation and smoothed in.

Powder rouge

Powder rouges were similar to face powders except that they were more highly coloured and opaque. This required higher concentrations of dyes and pigments and opacifiers like zinc oxide and titanium dioxide.

See also: Loose Face Powders

Loose powder rouges do not appear to have been very popular in the twentieth century, with most women preferring their rouge powder compressed into a compact.

Paste rouge

The paste or salve type of rouge is the easiest rouge to make. A simple anhydrous base can be made by blending mineral oils and waxes together to make an ointment.

Paraffin wax 48 parts White beeswax 6 parts White oil 160 fluid parts Perfume 5 fluid parts Colour 107-214 parts as required Make a small quantity of base and allow it to set. While the base is setting, sift the dry colour through the fine sieve, remembering that the colour cannot be too fine. Next weigh out the amount of base required and remelt. When liquid add it to the previously sifted colour. Mix thoroughly, heating again, if necessary, to keep the whole mass in a pourable condition. Now strain through the silk which has been stretched over the receptacle. any dry colour that has nor passed through is transferred to the mortar and ground as finely as possible, after which it is added to a small quantity of the molten mass, which is then strained. The perfume is added as usual when nearly cold.

(“Cream rouge,” 1935, p. 153)

Both dyes and pigments could be used in a paste rouge. The pigments would be dispersed through careful blending of the mixture but should a dye be required then a suitable solvent – such as castor oil – would need to be incorporated into the formula.

As these rouges do not contain water, they usually have a good shelf life as long as steps are taken to ensure that bacteria or fungi do not grow in them. Their tendency to ‘drag’ when applied could be reduced by including fatty esters to counteract the effects of the mineral oil or petroleum jelly.

Cream rouge

Although a cream rouge looks very similar to a paste rouge and, when advertised, little distinction was made between the two, cream rouges were formulated as emulsions so contained water. Technically almost any type of face cream could be made into a rouge by adding colouring and most early cream rouges were made using a cold cream or vanishing cream base.

Cold Cream Type % White beeswax 17.0 Oleic acid refined 14.0 Petrolatum, white 22.0 Water 31.25 Triethanolamine 6.0 Borax 1.5 Cosmetic lake color 8.0 Perfume 0.25 Mix the color into the petrolatum by use of a roller or ointment mill. Heat the water, add the triethanolamine and the borax. Melt the beeswax and the oleic acid. Add the triethanolamine solution and mix until thoroughly emulsified, then add the perfume and finally the color base. Mix thoroughly and if necessary run the entire mass through an ointment mill.

Vanishing Cream Type % Stearic acid (triple pressed) 20.0 Cetyl alcohol 3.0 Glycerin 8.0 Water 60.1 Potassium hydroxide 85% 0.6 Cosmetic lake color 8.0 Perfume 0.3 Proceed as with vanishing cream. Mix color and perfume into the cream base after it is cool and mill thoroughly.

(Thomssen, 1947, p. 290)

See also: Cold Creams and Vanishing Creams

Given that cream rouges contain both oil and water it was important to ensure that any colouring used was either soluble or insoluble in both the oil and water phase. If it was only soluble in one phase a mottled look would be produced. As they contained water, cream rouges were also susceptible to evaporation as well as bacterial and fungal degradation. As only small amounts of rouge tend to be used at any one time, these cosmetics had a long life so cosmetic chemists had to ensure that they were stable over the long-term; tight lids and preservatives were essential.

Compact rouge

Compact powder rouge was the most popular form of rouge but also the most difficult to manufacture successfully. It used a similar formulation to loose powder rouge but contained a binder to hold the powder together when it was compressed into a firm cake.

Above: Compact or compressed rouge from Max Factor with mirror and puff.

See also: Compressed Face Powders

The problems associated with manufacturing early compressed face powders also beset compact rouges. However, as the rouge tablets were smaller than compressed face powders, they were probably less likely to break or crack, a common problem with early forms of this cosmetic.

Given the rising popularity of portable compressed face powders many manufacturers developed compacts which included a large compressed face powder combined with a smaller compressed rouge.

Manufacturing compact rouge

Once the base and colours had been selected a manufacturer would need to select an appropriate binder such as a water-soluble gum or mucilage, a water-repellant oil, an emulsion or a dry metal stearate (Heinrich, 1957, pp. 257-258). The choice of binder determined some aspects of the manufacturing process.

If a gum or mucilage was used this was added to the coloured and perfumed base, mixed well, thoroughly pulverised and then immediately pressed into godets.

If a water-repellant oil binder was selected this was thoroughly mixed with a portion of the white base before it was added to the bulk powder. Colour and water was then added before everything was mixed, pulverised and pressed.

The emulsion method required the emulsion to be mixed into the coloured base until a stiff paste was formed. This was then spread out thinly on trays to dry out before being passed through a granulator to break it up. This was pulverised before the perfume was added and the rouge was mixed and pulverised again, then pressed into cakes as needed (Kempson-Jones, 1948).

Compressed rouge was pressed into metal godets – also known as pans, trays or bezels – which were generally made from tin-plate to limit rusting. The godets were often corrugated with a circular pattern to reduce the possibility of the rouge cake lifting when wiped with a puff. Some rouge manufacturers also used a non-hardening adhesive to secure the cake to the godet but a better method was to incline the side of the godet wall inward so that the lip of the wall overhung the cake – a practice also used in making powder compacts. Once pressed, the godets were then fixed into a suitable case with an adhesive.

Above: A Lournay compact rouge case dismantled to show the various parts. The metal godet (bottom right) has circular ridges for added grip; some rouge can still be seen on the plate. The walls of the metal godet are not inwardly inclined but there is no evidence that glue was used to help the rouge cake stick to the metal. The metal godet was originally fixed into the plastic container with adhesive; traces of glue can be seen in the base (top right).

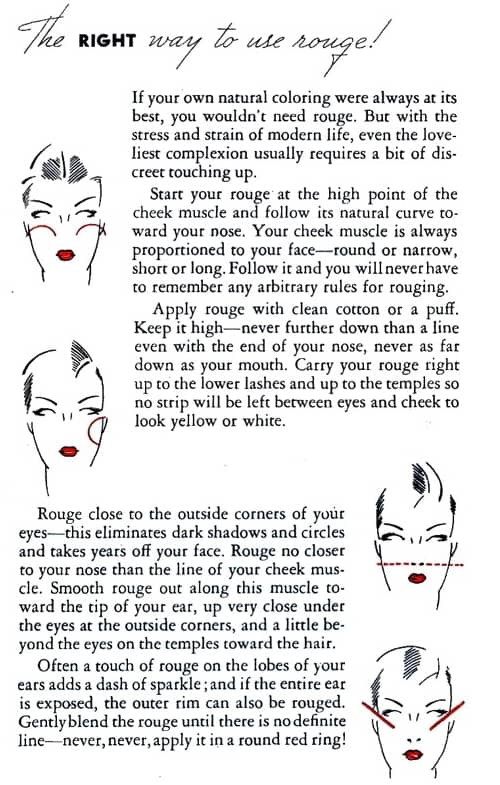

Applying rouge

Rouge was often applied to both the cheeks and the lips. Although all forms of rouge were used on the cheeks only liquid or paste forms were generally applied to the lips. Other places that were sometimes rouged included: the ears, especially the ear lobes; nails, to make the nail plate appear healthy; and the knees when dresses got shorter in the 1920s.

When used on the face, the type of rouge would determine when it was applied in the make-up routine. Liquid, paste and cream rouges were generally applied before powdering, while compact rouge was generally, but not always, added afterwards.

The most popular forms of Rouge are the dry, the liquid and the fatty.

The use of fatty Rouges is usually confined to the lips, while the dry and liquid forms are employed to beautify the skin.

Dry Rouge has the advantage of being more readily carried about, but the liquid is much more permanent in result and, if artistically used, defies detection.

Dry Rouges are usually rubbed on the skin with a rouge cloth or a bit of soft flannel. If applied before the face powder, the result is heightened. Liquid rouge is usually applied before any other preparation, in order to produce an underlying tint, which may be modified, if desired, by the after use of powder.

Liquid Rouges are best applied either pure or with distilled water, according to the strength of the Rouge and the effect desired, by the aid of a bit of wet absorbent cotton, care being taken to spread the preparation evenly and let it dry on the skin.

A good Liquid Rouge, such as Permanent Rose Tint, will not rub off on a dry handkerchief, nor does perspiration effect it. It may be used to color the lips, although our specially prepared Lip Rouge in sticks is more convenient.(Richard Hudnut, 1915, pp. 29-31)

By the 1920s and 1930s many cosmetic companies were providing more detailed descriptions of the best way to apply the rouge they manufactured.

Above: 1934 Richard Hudnut. Instructions for applying compressed powder rouge.

Also see the company booklet: New loveliness for you

Post-war developments

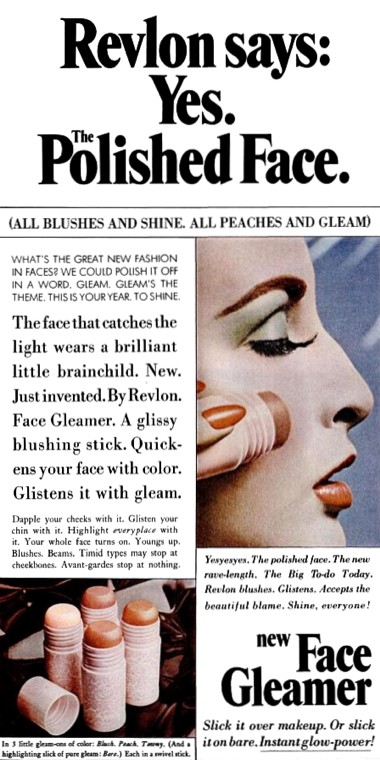

Many types of rouge used before the Second World War were not compatible with the newer, more highly coloured and opaque stick, cream and liquid foundations introduced in the 1940s and 1950s and their use declined. In an attempt to shore up sales, cosmetic chemists produced ‘new’ rouge formulations made by altering the base in which the pigments were embedded. Of these, stick rouges – generally marketed as ‘blushers’ even though they were not necessarily red – was probably the most important. Stick rouges had existed before the war; Revlon, for example, had introduced Cheek Stick in 1940, but the new stick blushers were wider and were generally used to sculpt the shape of the face rather than introduce rosy cheeks.

Liquid

Suspension: Pigment colourants suspended in water containing antisetting agents. Produces an inexpensive matte finish but may settle over time.

Lotion: Pigment colourants suspended in a liquid emulsion. Produces an easy blending controllable sheen as long as the emulsion is stable.Creamy

Water-free: Pigment colourants in a water-free cream. Stable and blends well but is greasy and the surface of the cream may sweat and wrinkle in the container as it ages.

Emulsified: Pigments in an water in oil (w/o) or oil in water (o/w) creamy emulsion. Produces an easily blending controllable sheen but may dry up in the jar.

Stick: Similar to lipstick. Stable and easy to apply but needs tight manufacturing controls.Solid

Cake: Dry compressed powder. Produces a long lasting matte finish. The cake may break and the colour may become too intense over creamy makeup.Gel

Anyhrous: Soap gel with oil as the vehicle. Has a built in applicator and produces a natural transparent look. May sweat, gel can become cloudy and the high surfactant concentration may result in skin irritation.

Hydrous: Gum-like gel with water as the vehicle, Stable, easy to apply but may thin and dry out.Aerosol

Foam: Pigment colourants suspended in an emulsion containing a propellant. Produces a transparent natural look but is difficult to control the amount applied and is expensive.(Modified from Navarre, 1975, p. 966)

Despite all these developments, rouge/blusher never achieved the sales growth seen in other cosmetics after the war. The tanning craze that started in the 1920s had largely put an end to the ‘peaches and cream’ look and even when lighter skins became fashionable again, reddened cheeks generally did not.

First Posted: 19th July 19th 2010

Last Update: 11th October 2022

Sources

The art of beauty. (1825). London: Knight and Lacey.

Beasley, H. (1878). The druggist’s general receipt book comprising a copious veterinary formulary numerous recipes in patent and proprietary medicines, druggist’s nostrums, etc. perfumery and cosmetics beverages, dietetic articles, and condiments. (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston.

Cream rouge. (1935). The Manufacturing Chemist. May, 152-153.

Cristiani, R. S. (1877). Perfumery and the kindred arts. Philadelphia: Henry Carey Baird & Co.

Daniels, M. H. (1958). Rouges. Drug and Cosmetic Industry. 83, 2, August, 162-163, 248-249.

deNavarre, M. G. (1975). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd. ed., Vol. IV). Orlando: Continental Press.

The duties of a lady’s maid; with directions for conduct and numerous receipts for the toilette. (1825). London: James Bulcock.

Haskell, G. (1936). Chemicals and Toilet Preparation Industry. London: Author. Reprinted 2010.

Heinrich, H. (1957). Rouge. In E. Sagarin. (Ed.). Cosmetics: Science and technology (pp. 249-261). New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc.

Hilfer, H. (1951). Rouges. Drug and Cosmetic Industry. 68, 2, February, 180-181, 246-247 .

Martin, M. (2009). Selling beauty: Cosmetics, commerce and French society, 1750-1830. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

The mirror of the graces. (1831) Boston: Frederic S Hill.

Poucher, W. A. (1932). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps, Vol 2 (4th ed.). London: Chapman and Hall.

Richard Hudnut. (1915) Beauty book containing some account of marvelous cold cream and other complexion specialities [Booklet]. New York: Author.

Thomssen, B. S. (1947). Modern cosmetics (3rd ed.). New York: Drug & Cosmetic Industry.

The toilette of health, beauty, and fashion. (1834). Boston: Allen and Ticknor.

The ugly-girl papers; or, hints for the toilet. (1875). New York: Harper & Brothers.

Some sources of red used before the development of synthetic dyes: madder, safflower, alkanet and cochineal.

1829 Different rouges listed in a French catalogue.

1893 Various rouges illustrated in a Dorin catalogue.

1919 Ingram’s Rouge. Shades: Light, Medium and Dark.

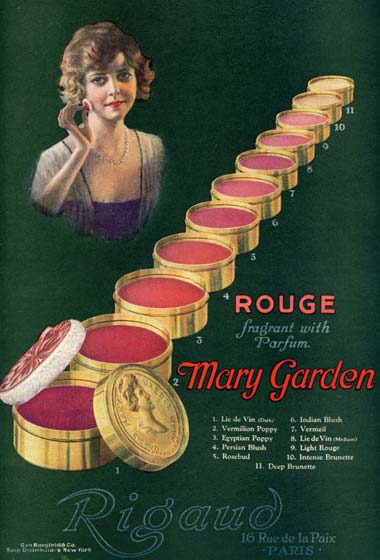

1920 Rigaud Rouges. Shades: Lie de Vin (dark), Vermillion Poppy, Egyptian Poppy, Persian Blush, Rosebud, Indian Blush, Vermeil, Lie de Vin (medium), Light Rouge, Intense Brunette and Deep Brunette. The line was named after the Scottish operatic soprano Mary Garden [1874-1967].

1922 Dorin Rouges. Ten shades of rouge not all of which are shown. The idea of varying the packaging colours for each shade was also used by Bourjois.

1925 Kerkoff Djer-Kiss Vanity Case that includes a compact rouge.

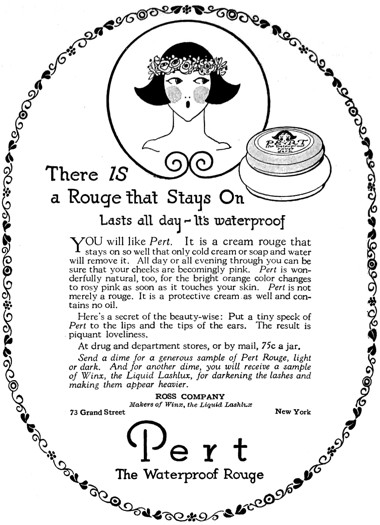

1923 Ross Company Pert Waterproof Rouge. Shades: Light, and Dark.

1924 Princess Pat Tint, a ‘changeable’ rouge that looked orange in the compact but went red on the cheeks when applied under the powder.

1924 Tre-Jur triple vanity case with compact face powder, smaller rouge compact and a lipstick.

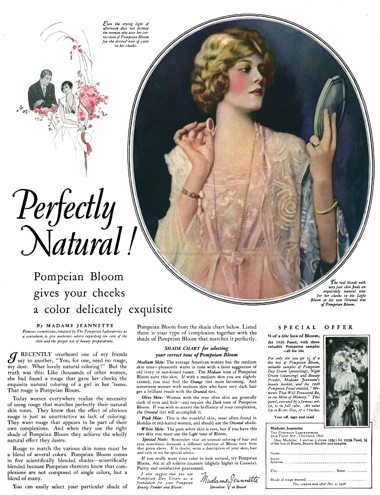

1926 Pompeian Bloom Rouge. Shades: Dark, Medium, Orange, Oriental, and Light.

1930 Dorothy Gray Cream Rouge.

1930 Clark-Millner White Rouge. This changeable rouge was white in the box but changed to a pale, rose shade when applied to the skin.

1932 The three-dot method for applying a cream rouge to the lips.

1935 Savage Rouge. Shades: Tangerine, Flame, Natural, and Blush.

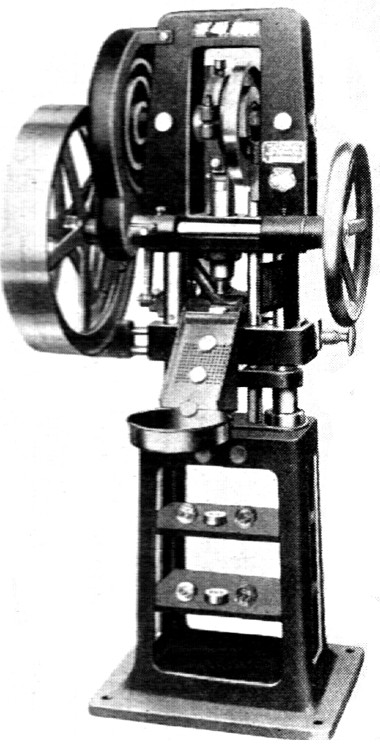

1936 Press for making compact rouge.

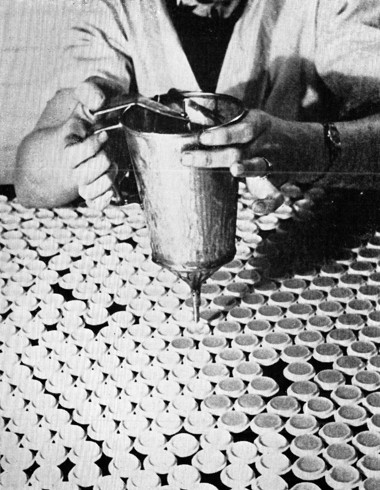

1937 Dispensing either cream or paste rouge into rouge pots using a hand-held gravity feeder.

1940 Revlon Cheek Stick colour harmonised with Revlon Nail Enamel and Revlon Lipstick.

1942 Dermetics Automatic Rouge, a red velvet puff encased in a plastic container. Rouge powder sifted through the weave in the chiffon velvet as the puff was rubbed across the cheeks.

1949 Nina Ricci Rouge Fluide.

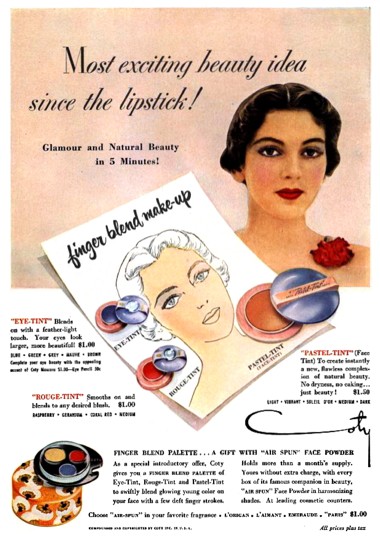

1950 Coty ‘Finger Blend Make-up’ which includes ‘Rouge-Tint’, a cream-based blush. Shades: Raspberry, Geranium, Coral Red, and Medium.

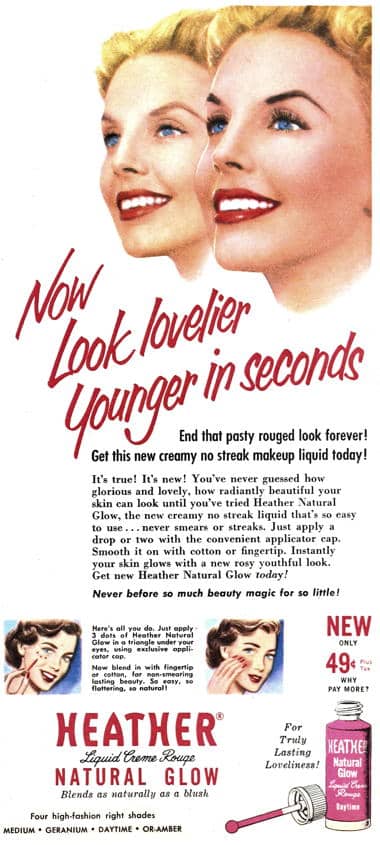

1954 Heather Natural Glow, a liquid-cream rouge in Medium, Geranium, Daytime, and Or-Amber shades.

1967 Revlon ‘Face Gleamer’ Stick Blusher. Shades: Blush, Peach, and Tawny. Highlighting was more concerned with accentuating the cheek bones than mimicking cheeks untouched by sun.

1972 Yardley Pot o’Gloss. Shades: Red Shriek, Boistrous Bronze, Emphatic Pink, Noisy Peach, Screechy Pink, and Clamerous Coral. This is a return to the older tradition of using a rouge on the lips.

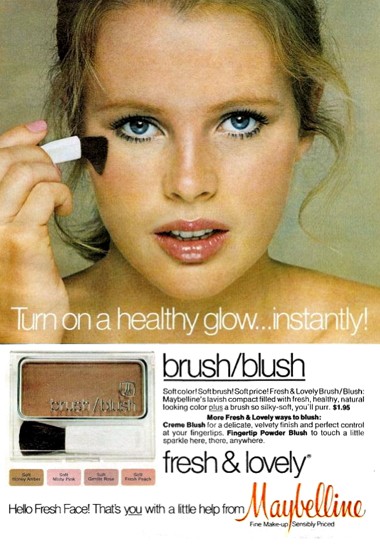

1978 Maybelline Creme Blush and Fingertip Powder Blush.