American Lipstick Wars

By the end of the Second World War, lipstick had become an essential make-up item for many women. Competition in the American lipstick market was fierce and no one battled for market share more resolutely than Charles Revson [1906-1975] of Revlon, then the number one seller of lipsticks in the United States. So, when the newly established cosmetics firm Hazel Bishop began a national campaign to sell its Long Lasting Lipstick in 1950, and got strong sales, Revlon responded and the American ‘Lipstick Wars’ commenced.

Hazel Bishop

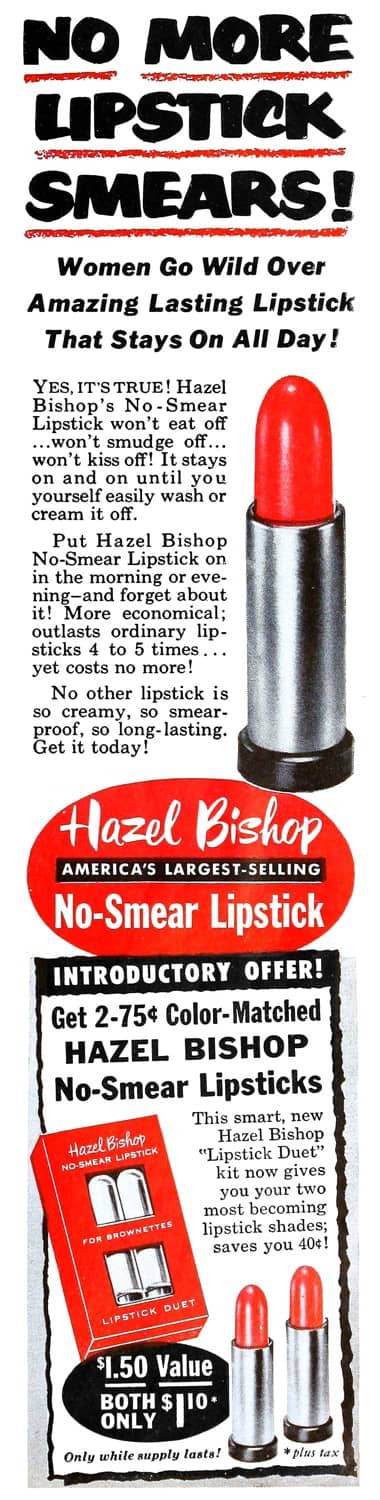

Hazel Bishop’s Long Lasting Lipstick – quickly rebadged as No-Smear Lipstick – was a type of lipstick commonly known as an ‘indelible’ or ‘high staining’.

Also see: Indelible Lipsticks

Retailing at US$1.10, No-Smear Lipstick debuted in six shades: Pink, Red Orange, Real Real Red, Medium Red, Secret Red and Dark Red. The lipstick has often been referred to as revolutionary but its success had more to do with the way it was marketed than how it was formulated. Raymond Spector [b.1904], who organised the advertising campaign for Hazel Bishop, promoted the lipstick extensively, first through metropolitan newspapers – using catchy phrases such as ‘Won’t Eat Off–Bite Off–Kiss Off’ – and then through radio and television promotions.

Above all else it was the use of television advertising, then a relatively new medium, that was responsible for Hazel Bishop capturing 25% of the American lipstick market by 1953. However, marketing on television was expensive and the company was spending over one-third of its gross income on advertising.

See also: Hazel Bishop

Indelible or high stain lipsticks had been on the market for decades but the success of Hazel Bishop’s No-Smear Lipstick generated a renewed interest in them. Most of the major American cosmetic firms soon introduced new indelible products, one of the first to respond being Revlon.

Revlon

Revlon had been selling lipsticks since 1939 in colours that complemented its range of nail enamels. Using print advertising, window displays and in-store promotions, Revlon’s lipstick campaigns through the 1940s concentrated more on the shade of the lipstick, fashion, and colour harmony than the qualities of the product.

Also see: Revlon (1945-1960)

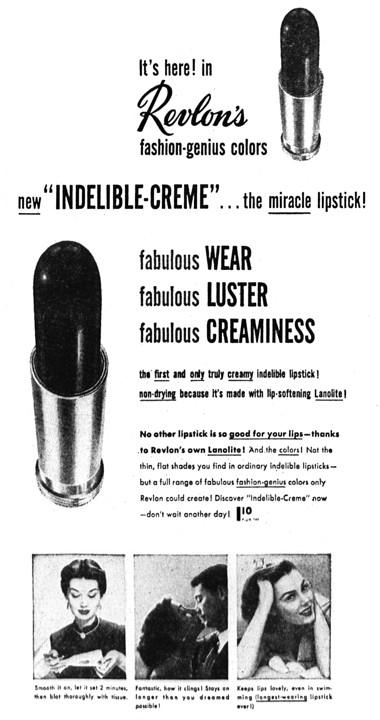

Revlon added Indelible-Creme Lipstick to its range in 1951 with the previous formulation thereafter being referred to as Regular. This new indelible formulation was advertised as containing ‘Lanolite’, a lanolin derivative that helped moisturise the lipstick and gave it a creamy feel. Initially offered in twelve Revlon fashion shades: Pink Lightning, Bachelor’s Carnation, Sweet Talk, Plumb Beautiful, Certainly Red, Scarlet Poppy, Touch of Genius, Pink Plum Beautiful, Stormy Pink, Snow Pink, Bravo, and Ripe Pimento, Revlon produced both Regular and Indelible-Creme formulations in all of its colour promotions after that including the highly successful ‘Fire and Ice’ campaign of 1952.

Revlon’s Indelible-Creme Lipstick was clearly modelled on Hazel Bishop’s. Like the Hazel Bishop indelible, women using Revlon’s Indelible-Creme were told to wait for the lipstick to set and then blot off the excess to stop it smearing. Revlon sold books of lipstick blotters specifically for that purpose. Revlon’s newspaper advertisements for the new lipstick also mimicked some aspects of the Hazel Bishop No-Smear Lipstick campaign.

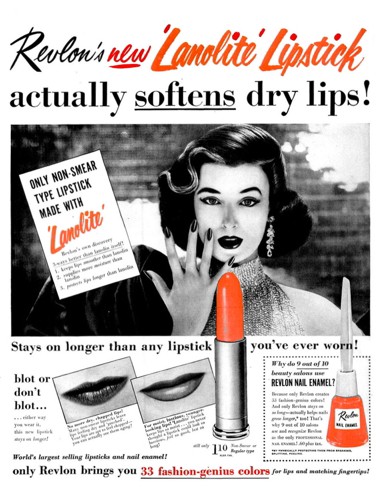

Unfortunately, Revlon was forced to abandon the name Indelible-Creme in 1953 when the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) stipulated that lipsticks could only claim to be ‘indelible’, ‘smear proof’, or ‘non-smear’ if the word ‘type’ was used as well. This forced Hazel Bishop to drop its No-Smear tag and, in 1954, required Revlon to replace its Indelible-Creme Lipstick with Revlon Lanolite Lipstick in non-smear and regular types. Revlon’s advertisements for this new lipstick accentuated its moisturising properties but sales were below expectations and failed to make much of an impact on the opposition. This meant that the first round of the ‘Lipstick Wars’ went to Hazel Bishop.

The situation deteriorated even further for Revlon, when Coty introduced a new indelible lipstick in 1955. This had good sales and Revlon’s share of the American lipstick market hit an all-time low (Abrams, 1977, p. 128).

Coty

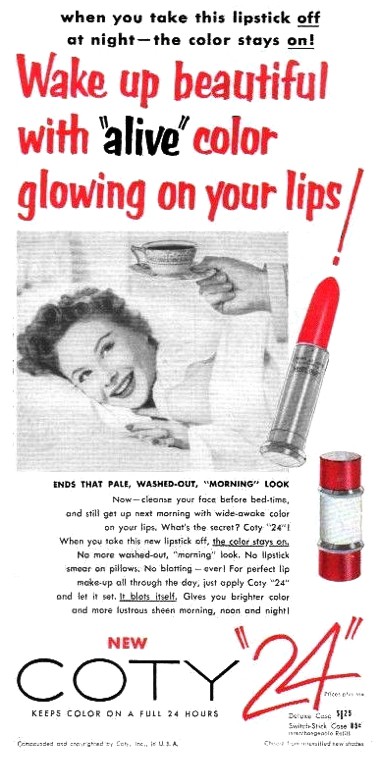

Unlike lipsticks sold by Hazel Bishop and Revlon, Coty’s new indelible lipstick “24” assured its customers that it did not need blotting. It sold well and helped make the 1954-1955 financial year Coty’s best post-war year to date.

The lipstick left a red stain on the lips even after it was removed at night, so a woman woke up next morning with some colour remaining. This might be considered a problem but the lipstick was promoted with the slogan ‘Wake up beautiful with “alive” color glowing on your lips!’ which turned a flaw into an asset.

In response to Coty “24” – and the lacklustre sales of Lanolite Lipstick – Revlon introduced Living Lipstick (the twenty-four hour type) with the line ‘Put living color on your lips’, a slogan that was very similar to the one coined by Coty. Lawyers became involved and the ‘Lipstick Wars’ heated up.

Battle of the lipsticks. Coty is suing Revlon, and Hazel Bishop is not exactly a disinterested spectator. Coty launched a new lipstick called “Coty 24” and for an advertising theme used “Wake up beautiful.” The idea was that the girl who used Coty 24 would wake up in the morning with “alive color on her lips.” Now, says Coty, Revlon has appropriated the advertising claim for it product, though “the color of said (Revlon’s) lipstick will not stay on the lips for any appreciable length of time after normal removal of the lipstick itself,” Revlon has responded with a counter suit. The Hazel bishop people have not sued yet. But you never know. They are murmuring that back in 1951 they advertised you would “wake up in the morning beautiful” when you used Hazel Bishop lipstick. That was long before Coty or Revlon got into the act.

(Kiplinger, 1955, p. 40)

Rather than resort to litigation, Coty simply informed International Playtex – who had a trademark on ‘Living’ (for Living Bras) – of Revlon’s use of the word and Revlon was forced to cease production of Living Lipstick, a victory for Coty. However, both Coty and Hazel Bishop would soon lose the lipstick wars to Revlon. In June, 1955 ‘The $64,000 Question’ premiered on the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) television network with Revlon as its sole sponsor.

Also see: Coty (post 1940)

‘The $64,000 Question’

Charles Revson was sure ‘The $64,000 Question’ was ‘crap’ but within four weeks of it debuting on CBS the quiz show was number one in the ratings. Revlon sales skyrocketed, almost tripled the following year, and its proportion of American lipstick sales went from 15% to 28% (Broadcasting Telecasting, 1956).

Above: 1955 On the set of ‘The $64,000 Question’.

Also see: Revlon and ‘The $64,000 Question’

The effect on Hazel Bishop and Coty was dramatic. Hazel Bishop lost money in 1955, 1956 and 1957, was forced to trim its advertising budget and never recovered. Coty also lost money in 1957 and 1958, partly through the need to increase its television advertising budget. So, although ‘The $64,000 Question’ went off the air in 1958, Revlon had weakened Coty, put Hazel Bishop on the path to its eventual demise, and established its dominance not only on the American lipstick market but across much of the American cosmetic industry as a whole.

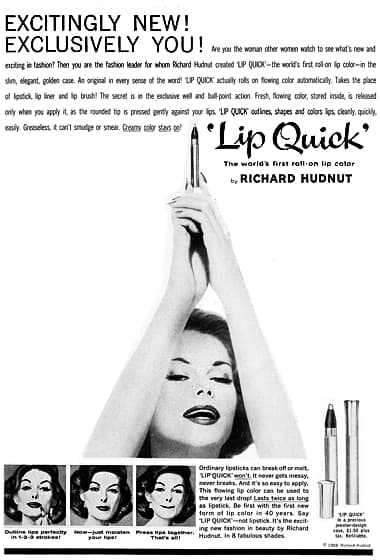

Lip Quick

In 1959, when the ‘Lipstick Wars’ seemed well and truly over, and Revlon had settled on Lustrous Lipstick – the fourth lipstick line it had introduced in the 1950s – Richard Hudnut released Lip Quick, a roll-on lipstick. This quickly captured 25% of the American lipstick market (Abrams, 1977, p. 138) and looked as though it would set off a new round of hostilities. Fortunately for Revlon, the device proved defective. The lipstick mass within the cylinder gummed up the ball-point and the dispenser then stopped working. The public lost faith in it and sales did not bounce back after Richard Hudnut fixed the problem.

Also see: Richard Hudnut (post 1945)

Collateral damage

Thanks to ‘The $64,000 Question’ Revlon won the ‘Lipstick Wars’ but the victory came at a cost. The move into television advertising ultimately cheapened the Revlon brand that Charles Revson had worked so hard to make high fashion and glamorous which resulted in it losing its air of exclusiveness. Revson tried numerous strategies in the 1960s and 1970s to move the Revlon brand, or parts of it, back ‘up-market’ but was largely unsuccessful and Revlon never regained the high status it had in the 1940s. This reduced Revlon’s ability to counter Estée Lauder’s growing domination of department stores.

First posted: 20th April 2015

Last Update: 4th July 2022

Sources

Abrams, G. J. (1977). That man: The story of Charles Revson. New York: Manor Books, Inc.

Broadcasting telecasting. (1956). Washington, DC: Broadcasting Publications, Inc.

Kiplinger, W. M. (Ed.). (1955). Changing times: The Kiplinger magazine. 9(7). Washington, DC: Kiplinger Washington Editors, Inc.

1952 Hazel Bishop No-Smear Lipstick. Originally called Lasting Lipstick it was first introduced nationally in the United States in 1950.

1951 Revlon Indelible-Creme Lipstick. Like Hazel Bishop’s No-Smear Lipstick it required time to set and then the excess had to be blotted off to stop it from smearing.

1954 Revlon Lanolite Lipstick in Non-Smear and Regular types with matching Revlon Nail Enamel.

1955 Coty “24” Lipstick. Unlike Revlon’s Indelible-Creme Lipstick or Hazel Bishop’s No-Smear Lipstick it did not require blotting.

1959 Richard Hudnut Lip Quick.