Indelible Lipsticks

As more women began to use lipstick in the twentieth century they discovered that it had an unfortunate tendency to come off on almost anything. Attempts were made early on to help keep lipstick on the lips and developments continued through the rest of the century. Lipsticks formulated with an improved holding power were advertised as being ‘long-lasting’, ‘deep-staining’, ‘stay-on’, and ’smeer-proof’, or something similar but I will call them all ‘indelibles’ although the term is not strictly correct.

Although lipsticks of the indelible type were found in all countries through most of the twentieth century they were most popular in the United States. There they had two periods of high consumer interest; the first in the 1920s and 1930s and the second in the 1950s. However, their formulation in each of these periods was very different.

Pigments and dyes

Up until the 1920s most lipsticks were coloured with pigments like carmine, a red pigment extracted from cochineal beetles. Carmine looked a deep red in the stick but was less intense when applied to the lips. If a brighter red was required, zinc oxide was added, while other lake pigments like yellow and vermillion were used to produce variations in shade. Typical formulations are listed below:

Daylight Stick, No. 1520 Carmine 50 Carmosine 50 Liquid paraffin 50 Soft paraffin—white 500 Ceresine 350 1000 (Poucher, 1932, p. 472)

Mineral oil (Russian, heavy) 64 ozs. Petroleum jelly, white 32 ozs. Ceresine 31 ozs. Paraffin wax, 50/52 33 ozs. Oil Carmine 1 oz. Scarlet Lake, cosmetic quality 15 oz. Red Lake 24 oz. (Jannaway, 1937)

The pigments lacked an intensity of colour and could be easily rubbed off, requiring the lipstick to be frequently reapplied. To make a longer-lasting lipstick, finely ground water-soluble dyes were sometimes added to the wax-oil base along with the carmine. These would stain the lips so that a colour would remain on them after the pigment was largely removed.

In addition to making the lipstick longer-lasting, these dyes fitted with the prevailing idea of the time; that the primary function of a lipstick was to enhance the natural redness of the lips rather than give it an ‘artificial’ colour. At first, natural dyes were used but these were soon supplemented with, or replaced by, synthetic dyes like eosin – a tetrabromo derivative of fluorescein that had been developed by Heinrich Caro at BASF in Germany in 1874.

Eosine stearate 100 Ceresine 100 Japan wax 200 Lanolin 400 Rectified spirit 190 Jasmin, No. 1055 10 1000 (Poucher, 1932)

Although dyes made colour last longer on the lips they all suffered from the same problem. Being water-soluble, the lips had to be moistened before the lipstick was applied to enable the dyes could stain the lips. This was inconvenient, produced uneven results, and sometimes allowed the colour to run beyond the lip-line producing unsightly stains (feathering) around the mouth.

One way around these problems was to use a liquid lip rouge and these had a reasonable following before the First World War. They consisted mostly of alkaline solutions of cochineal or carmine but there were some that contained the mercury salt merbromin (trade name Mercurochrome). However, being liquids, they were liable to drip and were easy to spill so, when good indelible lipsticks appeared, their popularity declined.

Bromo acids

Some time before 1920, water-insoluble fluorescein dyes were developed, the first of which was an acid form of eosin. It was orange in colour but at a pH of about 4 it changed to an intense red salt. Its lack of water-solubility should have meant that it was used as a pigment – and some lipsticks were made where this was the case – but solvents were found that enabled it to be put into lipstick as a dye. This allowed it to react with the lip tissue to produce a blue-red stain more intense than anything previously generated. In addition, being water-insoluble, it worked on dry lips, so many of the previous problems were avoided. Its effectiveness is reflected in the fact that it is still used today, listed as D&C Red No. 21 or CI 45380.

Other water-insoluble fluorescein dyes followed – none of which were pure red – including dibromofluorescein (D&C Orange No. 5, CI 45370), a yellow-orange stain; tetrachlorobromofluorescein (D&C Red No. 24, CI 45366), a weak-bluish-red stain; and later tetrachlorotetrabromofluorescein (D&C Red No. 27, CI 45410), a strong bluish-red stain. These fluorescein dyes came to be known as bromo acids, a term first coined in the United States (Redgrove, 1935). The first lipsticks using them were made by dissolving bromo acids in a solvent like stearic acid or acidic coconut oil before combining it with the waxes and the other ingredients that made up the lipstick. These sticks stained well but had a tendency to crumble with age (Sagarin, 1957). By the 1930s, an improved lipstick was developed using castor oil as the bromo acid solvent; a practice that I believe also began in the United States.

Castor oil

Castor oil can dissolve bromo acids because it contains a high content of ricinoleic acid – the only natural oil with this property. By modern standards it is not a great solvent for bromo acids but it had other qualities that endeared it to early formulators and it is still the main ingredient in some lipsticks on the market today. Its high viscosity, even when warm, helped to keep the pigments in suspension and its oily nature gave the lipstick gloss and emolliency.

Allergies and irritations

As the use of bromo acids widened, reports of irritation and allergic reactions – though still rare – increased. Although little could be done about allergies, it was later discovered that the irritation was mainly due to impurities in the bromo acids. Whatever the cause, there appeared to be a clear relationship between the concentration of bromo acids in the lipstick and the likelihood of irritation, so efforts were made to lower the amount of these dyes. To offset this, chemists searched for other solvents that would dissolve the bromo acids at higher levels than was possible using castor oil. Unfortunately, the chemistry of the day was not sufficiently advanced to achieve this so the problem was not fixed, and this may have contributed to the decline in consumer interest in indelibles in the 1940s.

Technicolor

Bromo acids would also create problems for screen make-up artists working on Technicolor films. Actresses that used lipsticks made with them off the set would have a blue cast on their lips when filmed. Perc Westmore discussed this problem in 1938 – note that he uses the term pigment as a general term for colour:

[A]ll lip rouges for street wear contain a definite amount of blue pigment invisible to the eye, but painfully visible to the color camera. These lip rouges are also of the indelible variety; they cannot be removed, as can ordinary make-up, by cold cream and washing. The pigment must wear off.

We have found that even after several days during which no such rouge is applied there is still enough of this blue pigment remaining to show through the Technicolor make-up and give the lips a bluish cast in the picture.

Therefore, no actress in a Technicolor film at our studio is allowed to wear ordinary lip rouge for her social make-up away from the studio. Instead we provide a special pure pigment lip rouge for street wear. It is not indelible, but this minor inconvenience is offset by the improved appearance of the player.(Westmore, 1938, p. 40)

Early alternatives

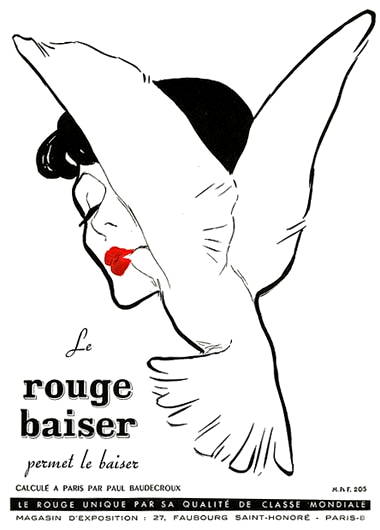

Not everyone in the 1930s used bromo acids to make indelible lipsticks. Apparently, the chemist Paul Baudecroux used eosin dissolved in propylene glycol to make Rouge Baiser (Appell, 1982), a lipstick he first introduced in France in 1927. If this is correct he would have been the first to do so commercially. A strong stain was produced with this lipstick as the eosin was in complete solution when it came in contact with the lips; some said it was too strong! However, as other chemists also discovered, using propylene glycol was not without its problems. As well as having an unpalatable taste, propylene glycol was affected by changes in the atmosphere – losing water when the air was dry and picking it up when humidity was high – with potential effects on the integrity of the lipstick.

Another approach was to mix the eosin-glycol into an emulsion stick, in much the same way that water-based materials are mixed with oils and waxes to make a cream. This produced nice, creamy lipsticks but they had problems similar to those suffered by Rouge Baiser and did not last long in the marketplace.

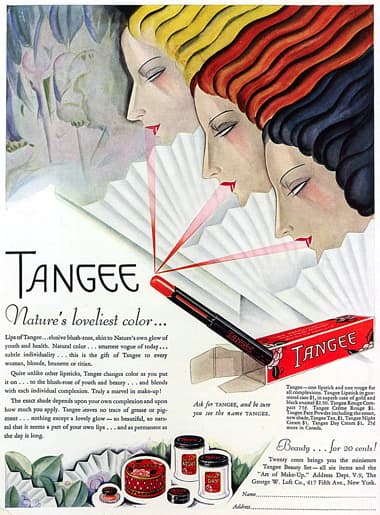

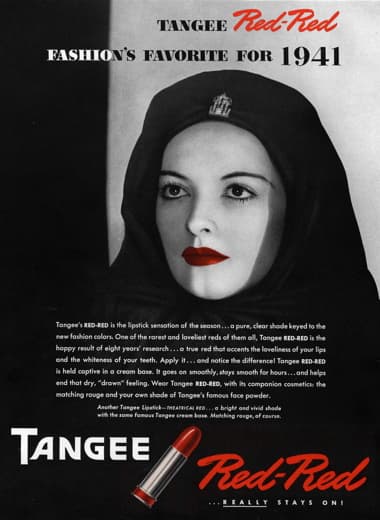

Changeable lipsticks

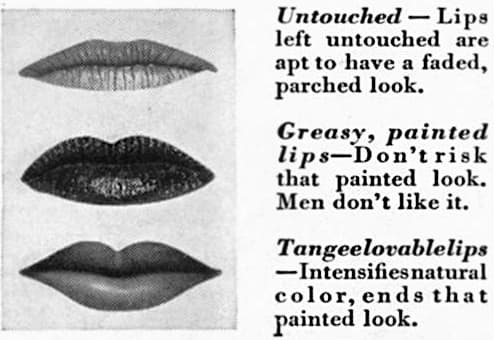

When used in lipsticks, bromo acids were usually combined with pigments but lipsticks were also made where the dyes were the only source of colour. When used alone, dyes could be used to make a changeable lipstick, an early example of which was first sold by Tangee in 1922. This lipstick looked orange in the stick – due to the eosin – but went red when applied to the lips. In a clever marketing campaign Tangee promoted the lipstick as being ‘natural’ and ran advertisements describing how it would allow the user to avoid looking ‘cheap’ and ‘painted’. It became the best-selling lipstick in the United States between the two world wars.

Unlike ordinary lipsticks

The trouble is, you never suspect yourself of a cheap appearance. Yet any ordinary lipstick hardens your mouth with a painted look. Tangee, however, is unique. Tangee cannot make your lips look painted!

Tangee isn’t paint. It’s different. It even looks different. In the stick, Tangee is orange. Does that mean orange lips, you say? Absolutely no! Put it on. Watch it change colour instantly to the one shade of blush rose perfect for you!(Tangee advertisement, 1934)

Above: 1938 Untouched, Painted and Tangee lips.

Tangee gave up on this marketing strategy when it introduced a range of coloured lipsticks after 1940, by which time the idea of using ‘paint’ had lost most of its stigma. However, it did not abandon its changeable lipstick and it is still on sale today.

See also: Tangee

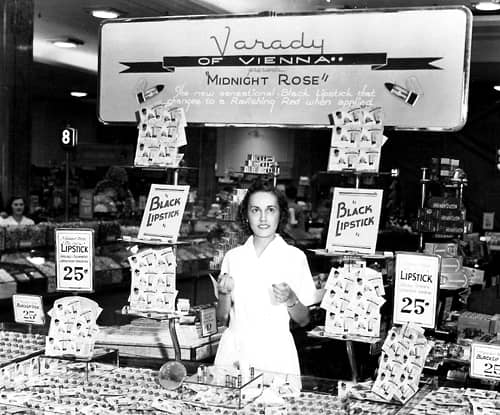

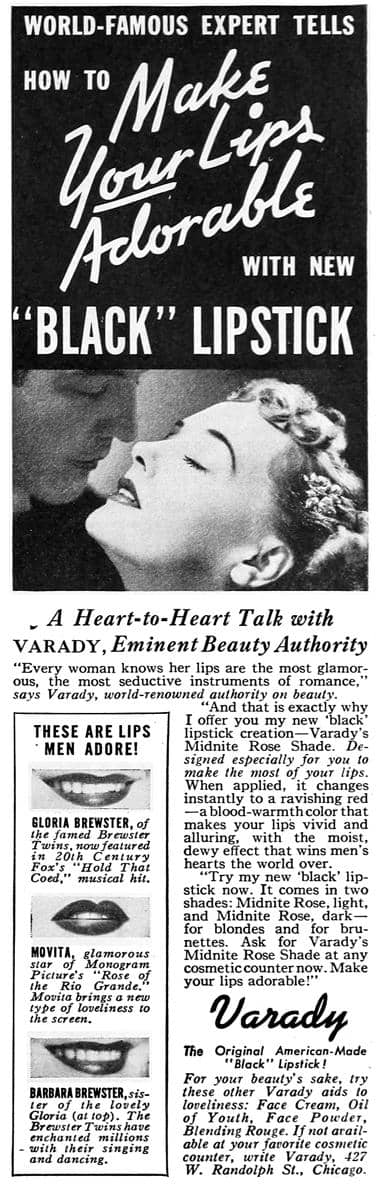

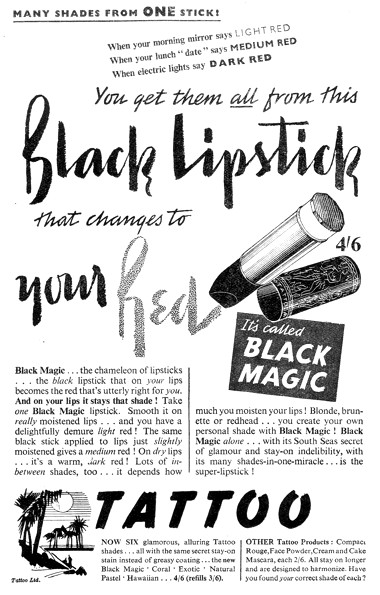

A second form of changeable lipstick, that was briefly in vogue in the late 1930s and early 1940s, were black lipsticks which changed to red on the lips. The idea seems to have originated with Paul Baudecroux, the chemist responsible for Rouge Baiser. Introduced in 1938, Rouge Baiser’s Black Lipstick came in six shades (Nasturtium, Light, Medium, Dark, Claret and Orange) with only the deeper shades looking black in the stick.

The lipstick contained both oil-soluble and water-soluble dyes but no pigments. The oil-soluble dye – that deNavarre suggests was D&C Red No. 18 (deNavarre, 1975) – gave the sticks a very dark red, almost black colour. As the skin on the lips does not contain enough free oil to be stained by the oil-soluble dye, it did not become lodged on the lips and quickly rubbed off, leaving the water-soluble dye behind which stained the lips red. Moistening the lips before applying the lipstick helped the water-soluble dye to work and produced a better result. The casing of the lipstick appears to have had a twist top to help seal it, presumably to reduce the possibility of it drying out or taking up moisture with changes in the weather.

Rouge Baiser’s black lipsticks were very expensive – selling for $5.00 in the United States when most lipsticks were $1.00 or less – but cheaper black lipsticks were soon released by makers like Tattoo, Varady and Tokalon. After an initial vogue, the novelty factor wore off and the lipsticks faded from the market.

Above: Varady of Vienna Black Lipstick. Despite the name, Varady was an American brand.

In 1940, Vivaudou produced a green, indelible lipstick with a minty fragrance called Viva-Caprice that also turned red on application. It came in two shades (Natural and Brunette) that Vivaudou said “you can’t drink off, smoke off or swim off”, a marketing phrase similar to the one used a decade later to sell Hazel Bishop indelible lipsticks. Like black lipsticks, it was a gimmick that did not last very long.

Pigmented lipsticks

Most lipsticks on the market contain pigments. In general, the difference between a pigmented lipstick that is indelible and one that is not, lies in the amount of bromo acids or other dyes included in the mixture.

To keep their customers happy, cosmetic formulators making indelible lipsticks with pigments tried to make the visible stick colour match the shade left on the lips as closely as possible. In the 1920s this was not a major problem as shade ranges were generally limited and, as yet, it was not the fashion to match lipsticks with clothing or nail polish. Matching the colour between lipsticks and rouge was considered important, but as these were made with similar pigments this was fairly easy to achieve.

Early nail polishes were coloured with dyes but during the 1930s these were replaced with opaque cream polishes made with pigments. As nail polish became more prominent it became increasingly fashionable for women to match their nail polish colour with their lipstick. This led to a greater demand for lipsticks made with pigments and produced a corresponding decline in interest in pure indelibles.

See also: Nail Polish

Indelibility also become less important as women gave up any pretense to using a lipstick that looked natural. The 1940s saw women move to creamier lipsticks that had a high gloss, a moist look and came in wide colour ranges. Colour was heavily promoted by cosmetic companies from the late 1930s all the way up to the Second World War, as was colour coordination with clothing, complexion, eyes, hair and nail polishes.

A new wave of indelibles

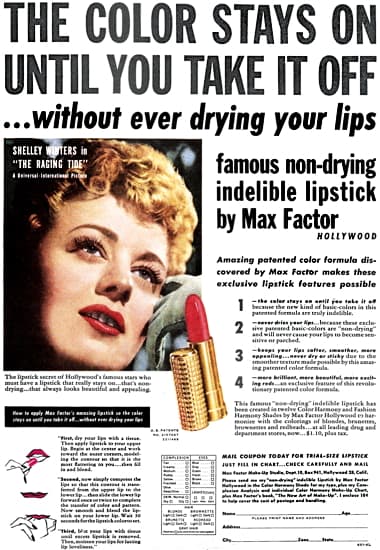

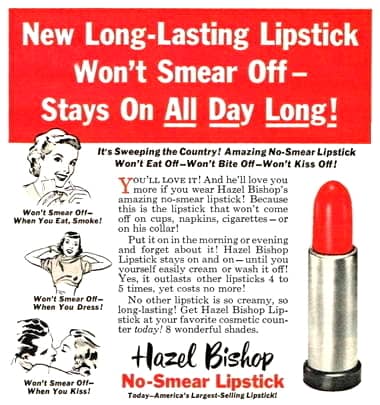

Indelibility came back into vogue in 1950, when Hazel Bishop introduced her Lasting Lipstick, a pigmented, indelible lipstick. It captured of 25% of the American lipstick market in a few short years, beginning what was known as the ‘lipstick wars’ in the United States.

See also: Lipstick Wars

With its ‘Won’t eat-off, bite-off or kiss-off!’ and ‘It stays on you not on him’ advertising slogans – Hazel Bishop’s Lasting Lipstick ushered in a new wave of indelibles that attempted to overcome the main problem of the creamy lipsticks of the 1940s, namely that they left marks on everything they touched.

Hazel Bishop’s solution to the problem of lipstick marks required a good deal of work on the part of the user, as a company sponsored publication from 1957 points out:

Here is the correct way to apply lipstick:

1. Make sure your lips are dry, with no traces of old lipstick.

2. With your lipstick or lipstick brush, start your design on the upper lips, moving from the center to the corners of the mouth slowly and surely. Then, in the same way apply lipstick to the lower lip. Many women like to apply the basic design with the lipstick, then fill in corners and round out small curves with a lipstick brush.

3. Check to make sure there are no uncovered areas, including the inside of the lips, so there is no sharp line of demarcation when you smile or talk.

4. Wait a few minutes, without smoking, eating or drinking, for your lipstick to set.

5. Next, to make your Hazel Bishop Long-Lasting Lipstick absolutely smearproof, blot, blot, blot until no more lip print appears on the tissue. Then you can be sure your Hazel Bishop Lipstick won‘t come off on cigarettes, coffee cups, glasses or “him”. It will stay on all day, even all through the night, until you take it off.

6. Glance at your teeth in the mirror to make sure there are no lipstick traces on them.(Archer, 1957)

See also: Hazel Bishop

One formulation that originated in this period was to combine the advantages of using a glycol with those of castor oil by using polyethylene glycol monoricinoleate. This acted as a mutual solvent for both polyethylene glycol and castor oil, a useful feature.

Indelibility claims

The success of Hazel Bishop saw many American cosmetic companies increased the staining power of their lipsticks through the 1950s. These new indelibles included Coty’s Coty “24” (1955) as well as Revlon’s Indelible-Cream (1951) and Living Lipstick (1955). In the United States, these new indelible lipsticks attracted the attention of the American Federal Trade Commission (FTC) who ruled on the claims they made. In a 1953 letter the FTC deemed that ‘longer lasting’ and ‘less likely to smear’, were appropriate but disallowed the terms ‘indelible’, ‘smear-proof’ and ‘non-smear’ in advertising, unless the word ‘type’ was used with the description. This ruling of course did not apply elsewhere in the world.

Pigment plus stain

The 1950s demand for indelibles in America was largely generated by massive television advertising campaigns. However, unlike the 1930s, increasing the staining power of lipsticks was not going to be enough to ensure sales in the longer term. What women really wanted was a lipstick that combined the qualities of the creamy lipsticks they had used in the 1940s with one that lasted longer on the lips and did not come off on everything their lips touched. Hazel Bishop knew this and strived to increase the adherence of the pigments in her lipsticks as well.

[T]he smear-proof lipstick derives its color from pigment plus stain, rather than from stain alone. This is important because, without pigment, the lip application has a “thin water-colored” look which, in my opinion, is neither satisfactory or desirable to the American women.

(Letter from Hazel Bishop, AP&EOR, 1953)

This has been the picture ever since. Women want a lipstick that is creamy, has a good colour range and stays on their lips. This cannot be achieved by using dyes alone. Although new dyes and solvents were introduced, formulators also worked to find ways to make pigments ‘indelible’ as well. Fortunately, the chemical industry, perhaps stimulated by the war effort, was increasingly able to provide cosmetic chemists with the raw materials they needed to realise this. So, as the 1950s moved into the 1960s, and deeper red colours gave way to corals, pinks and pearlescent shades, pigments not stains would be more dominant and any good-quality lipstick became longer lasting.

See also: Lipsticks

First Posted: 23rd July 2012

Last Update: 25th February 2021

Sources

Albo, R. (1971). Indelible lipsticks: Some technical aspects. Soap Perfumes & Cosmetics. February, 92-93, 104.

Appell, L. (1982). Cosmetics, fragrances and flavors: Their formulation and preparation with an introduction to the physical aspects of odor and selected syntheses of aromatic chemicals. Whiting, NJ: Novox.

Archer, A. (1957). Your power as a woman: How to develop and use it. New York: Hazel Bishop, Inc.

deNavarre, M. G. (1975). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics (2nd. ed., Vol. IV). Orlando: Continental Press.

Fishbach, A. L. (1955). Lipsticks—their formulation, manufacture and analysis. The American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review. March, 31-35.

Hilfer, H. (1951). Indelible lipsticks. The Drug and Cosmetic Industry. 69(3). 314-315, 417.

Jannaway, S. P. (1946). Lipsticks: Part 1. The Perfumery & Essential Oil Record. January, 3-9.

Kalish, J. (1938). Tested formulas for liquid lip rouges. The Drug and Cosmetic Industry. 43(6). 668-669.

Redgrove, H. S. (1935). A note on lipstick manufacture. The Manufacturing Chemist. April, 123-124.

Sagarin, E. (Ed.). (1957). Cosmetics: Science and technology. New York: Interscience Publishers, Inc.

Westmore, P. (1938). Make-up specialists can do much to assist the cinematographer. American Cinematographer. 19(1), January, 13, 40.

Heinrich Caro [1834-1910], colourist, chemist and technical leader at BASF from 1868-1888 where he developed eosin.

1929 Tangee Lipstick.

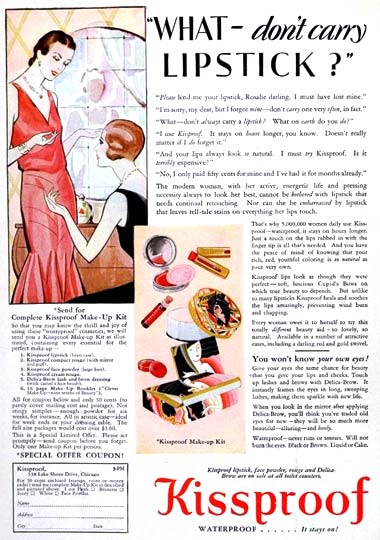

1930 Kissproof Cosmetics.

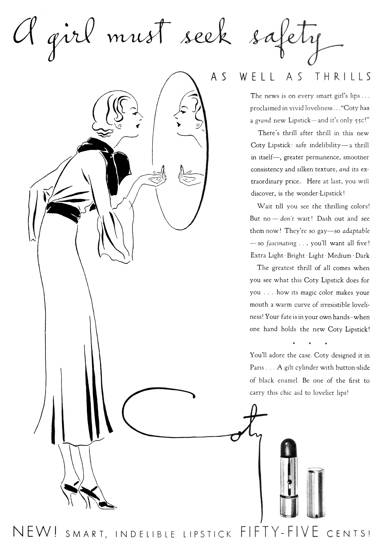

1932 Coty Indelible Lipstick.

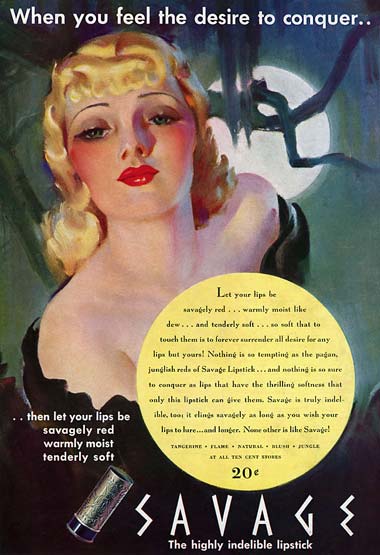

1936 Savage. By 1946 the company would have 5 shades: Jungle (a vivid red), Tangerine (orangish), Flame (fiery), Natural (blood colour), and Blush (changeable).

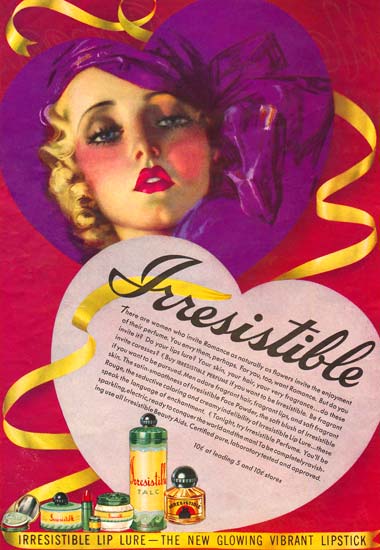

1938 Irresistible. The “creamy indelibility of Irresistible Lip Lure”.

1938 Varady Black Lipstick.

1939 Tattoo Black Magic Lipstick.

1940 Tangee Red Red.

1949 Rouge Baiser.

1951 Max Factor Indelible Lipstick.

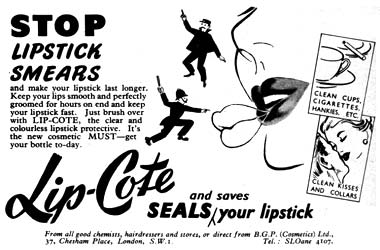

1951 Lip-Cote attempted to solve the problem of smears by coating the lipstick with a colourless film.

1952 Hazel Bishop No-Smear Lipstick.

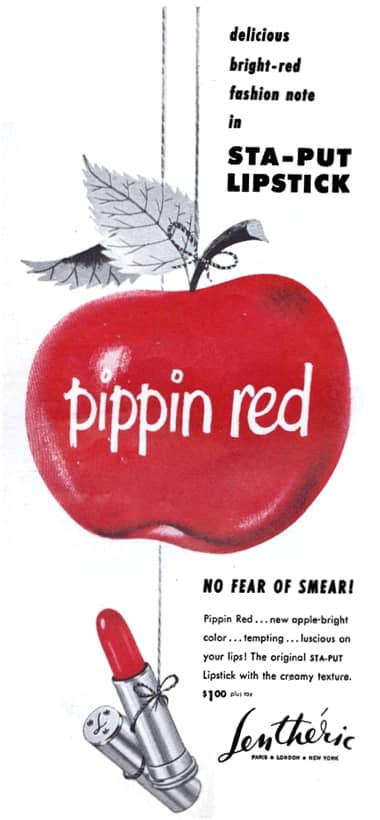

1952 Lentheric Pippin Red Sta-Put Lipstick.

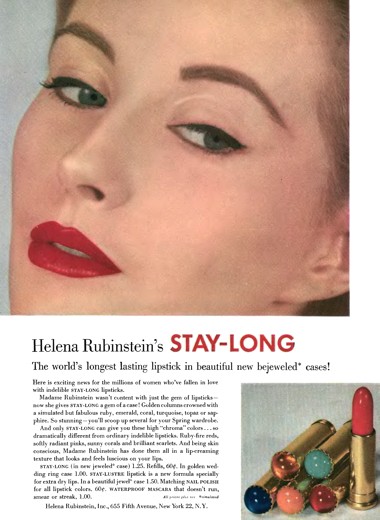

1953 Helena Rubinstein Stay-Long lipstick.

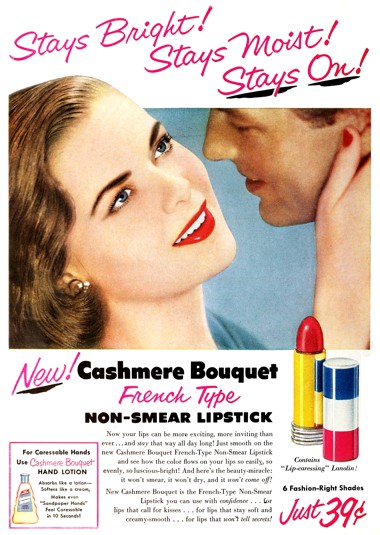

1953 Colgate-Palmolive Cashmere Bouquet French Type Non-Smear Lipstick.

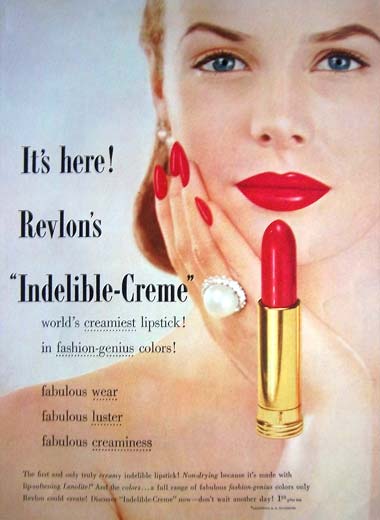

1951 Revlon Indelible-Creme. Revlon was forced to abandoned this lipstick in 1953 when the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) got agreement from advertisers that lipsticks could only claim to be ‘indelible’, ‘smear proof’, or ‘non-smear’ if the word ‘type’ was used with such descriptions.

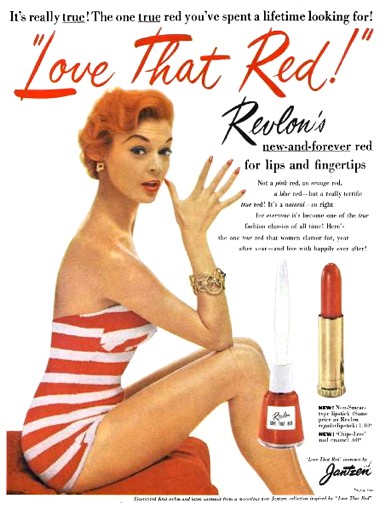

1954 Revlon’s Love That Red! shade in Non-Smear-type lipstick and Chip-Less nail enamel. As the word ‘type’ was used, Revlon avoided problems with the FTC over the naming this lipstick ‘non-smear’.

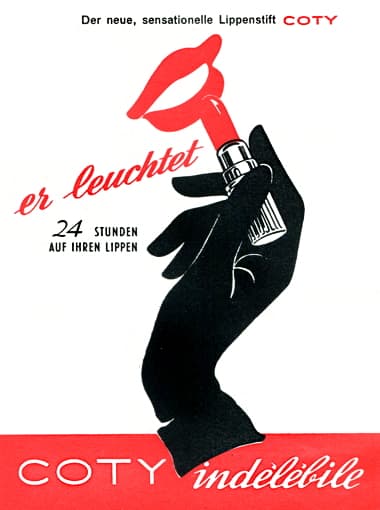

1960 Coty “24” (West Germany).