Maybelline

The rise of Maybelline from a small mail-order firm to a global cosmetics business is impressive. The company is now called Maybelline New York but its early fortunes, like those of Max Factor and the Westmore Brothers, were tied to the growing motion picture business in California.

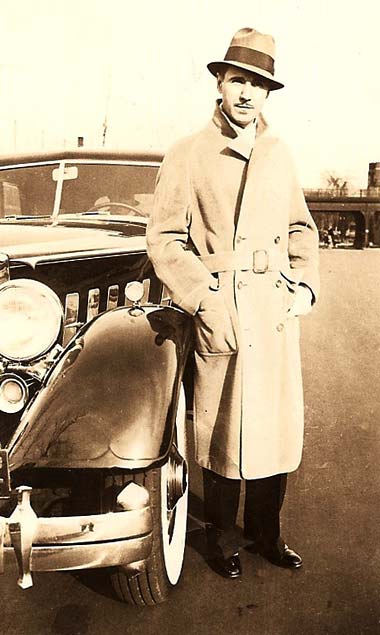

Thomas Lyle Williams

Known by those close to him as Tom Lyle, the founder of Maybelline was entrepreneurial, hard working, prepared to take advice, and loyal to friends and family. His good looks and ability to get on with people were undoubtedly of great assistance. In 1912, aged 16, he moved from Morganfield, Illinois to Chicago and got a job with Montgomery Ward, a mail-order catalogue business. After experimenting on his own with a variety of mail-order ventures he left Montgomery Ward in 1914 to focus on his own business. By then he had started a long-term romantic relationship with Emery Shaver who joined him in the venture.

Above: Thomas Lyle Williams and Emery Shaver [1903-1964].

The following year he wired his sister Mabel to come to Chicago to help with the business.

Maybell Laboratories

There are two stories about how Lyle got into the eye make-up business, both involving his sister Mabel. The first, is that he watched her fix her singed eyebrows using a mixture of Vaseline, ash and coal dust, a trick she apparently got from ‘Photoplay’ magazine. The second, that he saw her rubbing oil into her eyelashes and eyebrows to darken them and keep them healthy. Origin stories are notoriously unreliable and neither of these tales may be true. Lyle may have just copied an exisiting mail-order cosmetic he had seen in a movie magazine.

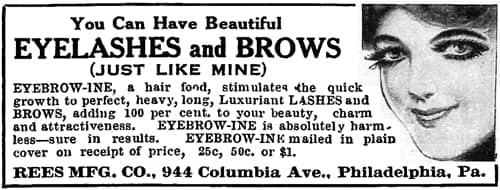

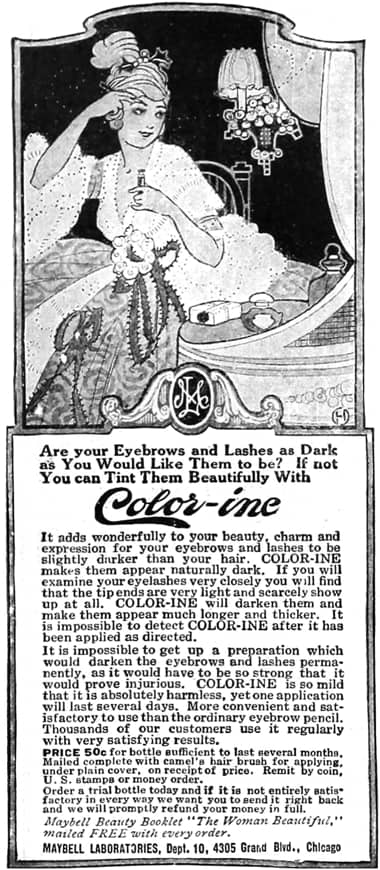

Above: 1916 Eyebrow-Ine. One of many similar products that were on the market when Tom Lyle introduced Lash-Brow-Ine.

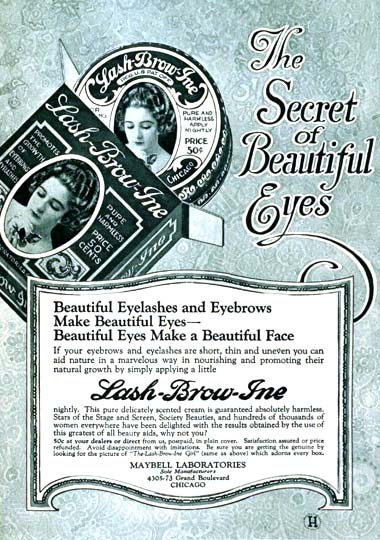

Whatever the truth, seeing an opportunity to make a product to sell through his mail-order business, Lyle created a mixture he hoped would sell. Unfortunately, when Mabel applied it to her lashes it ran into her eyes and stung them badly. Undaunted, Lyle sought professional advice and commissioned Parke-Davis, a wholesale drug manufacturer, to make a suitable product. The result was a scented cream consisting of refined white petrolatum along with several oils to add sheen. It did not contain any colouring agent but it seemed to ‘brighten the eyes’ (Williams & Youngs, 2010, p. 22). He called the product Lash-Brow-Ine, selecting the name partly because of its similarity with other eyelash and eyebrow products already on the market. This decision would create problems for the company later on.

Lash-Brow-Ine was packed into small aluminium containers and sold through mail-order in two sizes, at fifty cents and one dollar.

Above 1917 Lash-Brow-Ine in aluminium package.

Using money he got from his brother Noel to get this new venture off the ground, Lyle acquired product and packaging and placed an advertisement for Lash-Brow-Ine in ‘Photoplay’ in 1916. As cash came in, it was used to place advertisements in other magazines such as the ‘Pictorial Review’, the ‘Deliniator’, and the ‘Saturday Evening Post’ and so the business grew (Williams & Youngs, 2010, p. 25).

Advertising for Lash-Brow-Ine claimed that it ‘nourished and promoted the growth of eyelashes and eyebrows’. Lyle was canny enough to suggest that you needed to use “two to three small boxes before any marked improvement is noted”, thereby ensuring a number of sales before dissatisfaction might set in. Pamphlet material that came with the product also suggested it could also be used to cure baldness. Although we would now consider these claims to be untrue, at the time it was commonly believed that substances like Vaseline, olive oil and lanolin would stimulate hair growth.

How to use “LASH-BROW-INE”

Take a little “LASH-BROW-INE” on the tip of the finger and rub gently over the Brows and Lashes, always rubbing in the direction in which the hair grows. Be sure to rub well into the roots, and then take a soft cloth and wipe around the Brows and Lashes, leaving the “LASH-BROW-INE” only where you wish the hair to grow. To produce the very best results the very tip end of the Lashes should be clipped every two months. The clipping should be done by another person, using small manicure scissors, so as only to clip the tip ends. The Eyebrows should never be clipped.(Lash-Brow-Ine pamphlet)

See also: Eyelash Growers

Following the success of Lash-Brow-Ine, Lyle commissioned other products from Parke-Davis including: Odor-Ine Toilet Lotion, a deodorant; Color-Ine, an eyebrow and eyelash tint; Lily of the Valley Face Powder; and Maybell Beauty Cream, Rouge and Lipstick. None of these additional products produced good sales and all were later dropped.

Maybelline

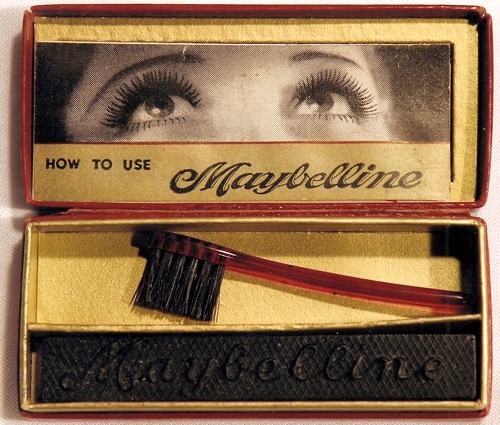

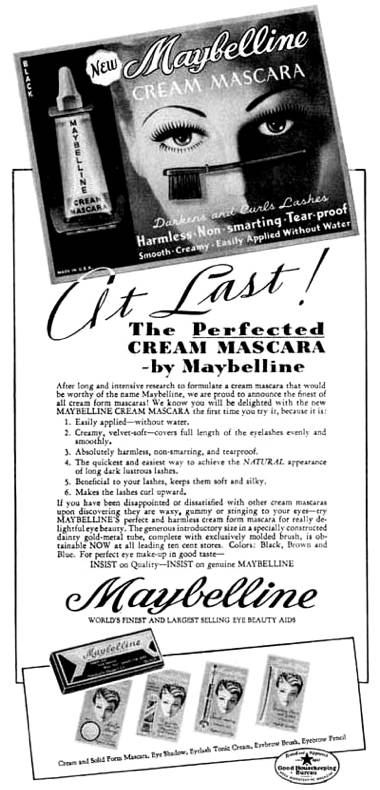

In 1917, again with the assistance of Parke-Davis, Maybell Laboratories began production and sale of a cake eyelash and eyebrow beautifier. The exact composition of this product is unknown but it was most likely a sodium stearate cake mascara also known as ‘water cosmetique’ or ‘mascaro’.

See also: Water Cosmetique and Cake Mascara

Like other products of its type the colouring agents were suspended in a base of sodium stearate soap. The soap and pigments were mixed together, extruded into strips, stamped and dried. The product was applied by first wetting the cake, then using a small brush to lift and apply the colour to the eyebrows and eyelashes. Early versions could irritate the eye but later versions made with triethanolamine stearate were less smarting.

Above: Maybelline eyelash beautifier packed in a box made by the Pictorial Paper Package Company of Aurora, Illinois. The brush was made by the Autograph Brush Company of New York City. The product form is almost identical to earlier French eye cosmetics.

The new product named Maybelline came in two shades, black (containing lamp-black) and brown (containing iron oxides) and was sold for seventy-five cents in a small box with a picture of the Maybell Girl on the top. The box included a rectangular cake of product stamped with the name Maybelline, a small bristle brush and a mirror attached to the inside of the lid. It was advertised as being an “ideal, harmless preparation for darkening eyelashes and eyebrows”.

In 1920, Lyle’s decision to use the name Lash-Brow-Ine came back to bite him when he lost an appeal over a trademark dispute with Benjamin Ansehl of St. Louis, Misssouri. The loss meant that the business could no longer use the name Lash-Brow-Ine and this cemented the use of Maybelline in all later branding and advertising.

In 1924, the growing business was relocated to larger headquarters at 5900 North Ridge Avenue, Chicago. The new headquarters also came with a new business name with Maybell Laboratories, renamed Maybelline in 1923.

Above: 1932 Employees standing outside the Maybelline building at 5900 North Ridge Avenue, Chicago. The front entrance is to the left.

Above: The front entrance of the Maybelline Building on Ridge Avenue in Chicago as it is today. The new building owners removed the metal push bar across the door with the word Maybelline spelled out on it but did not remove the Maybelline M above the door.

Growth and development of the company continued unabated for the remainder of the decade. A water-proof liquid mascara, applied with a paint brush built into the lid, was introduced in 1925 and Maybelline was promoted, in both its solid and water-proof liquid forms, in black and brown colours. In 1929, eyebrow pencils and eye shadow were added to the product line-up. The eyebrow pencils were also sold in black and brown but the eye shadows came in blue, black, brown and green, with violet added the following year.

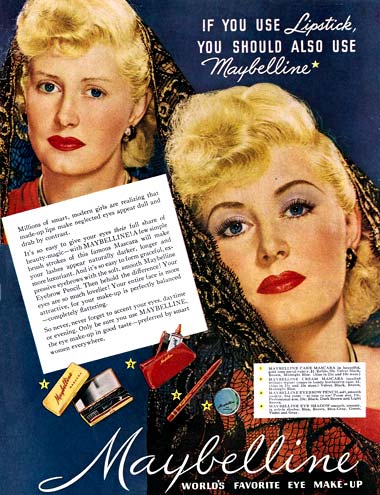

Promotion continued to play an important role in the success of the company with Maybelline spending over one million dollars on advertising between 1915 and 1929 (Williams & Youngs, 2010, p. 99). A lot of advertising featured actresses including Phyllis Haver, Ethel Clayton, Viola Dana, and Natalie Moorhead. Cross-promotion of this sort was critical to the success of Maybelline but was also important to the actresses and the movies they appeared in.

Both stage and screen had helped promote the use of eye make-up in the 1920s. The Ballets Russes, who toured the U.S. in 1916 and 1917, demonstrated an exotic glamour that relied, in part, on make-up to accentuate their eyes. In the movies, the vamp look used by actresses such as Theda Bara and Pola Negri also created a demand for eye make-up from women who wanted to look like them. Unfortunately, the vamp look was also associated with risqué costumes and suggested a certain looseness of character. This led to an association between eye make-up and immorality, a state of affairs that lasted well into the 1950s.

Mascara

Maybelline introduced eye shadow and eyeliner into its product line in 1929, which meant that Maybelline was for more than just eyelashes and the original product was renamed Maybelline Eyelash Darkener and then reformulated in 1931. In 1933, the ‘eyelash darkener’ began to be referred to as mascara, a process that was completed by 1935. This was rather late in the day as Helena Rubinstein, Dorothy Gray, Marie Earle and others had been using the term for years. Lyle’s decision to start using the term may have been to help Maybelline separate its products from the hair dyes associated with the Lash Lure scandal of 1933.

For absolute safety in darkening your lashes use genuine, harmless Maybelline.

Non-smarting, tear-proof Maybelline is NOT a DYE, but a pure and highly refined mascara for instantly darkening and beautifying the eyelashes.

For over sixteen years millions of women have used Maybelline mascara with perfect safety and most gratifying results(Maybelline advertisement, 1934)

See also: Lash Lure

Respectability and quality

The early 1930s were a difficult years for Maybelline but from adversity came strength. American production of toiletries and cosmetics declined from US$193 million in 1929 to US$97 million in 1933 and the number of cosmetic companies almost halved from 815 to 490 (Jones, 2010, p. 109). The companies most at risk were those at the lower, mass-market end, which included Maybelline. As well as the general economic difficulties caused by the depression, eye make-up came under attack because of its associations with flappers and the perceived immorality of the 1920s movie industry. Then, in 1933, the Lash Lure scandal caused a temporary drop in sales of all mascaras.

In 1931, in an attempt to improve sales, Maybelline introduced a ten-cent trial ‘purse size’ product that could be ordered using a mail-order coupon. This was so successful that it was eventually made available through point-of-sale outlets as well. Moves were also made to improve the company’s distribution system, particularly outside of the Chicago area, and packaging and display cartons were redesigned to make them more visible.

The use of movie stars remained an important part of Maybelline’s advertising strategy but, in the 1930s, endorsements from actresses were more sober in tone, a reflection of changes in the motion picture industry which adopted self-censorship in 1934 through the Production Code and also toned down its more lurid aspects. The company also began to use more models in the before and after shots. This may have abeen due to competition for movie star endorsements from Max Factor and the Westmores.

See also: Max Factor

Maybelline added radio to its advertising arsenal in 1934 when ‘The Maybelline Hour’ began broadcasting on WFNT out of Chicago (Williams & Youngs, 2010, p. 134).

Maybelline, along with a number of other mascaras, received favourable reports in the widely read book ‘Skin deep: The truth about beauty aids‘ published in 1934. However, given that the Lash Lure scare of 1933 had hurt sales, Maybelline sought to protect itself from questions regarding the quality of its products by obtaining the ‘Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval’ which was placed prominently in most advertisements for the rest of the decade. Phrases like ‘contains no dye’, ‘absolutely harmless’ and ‘perfect safety’ were also inserted liberally in advertising copy.

Product packaging was also upgraded as part of a drive to associate Maybelline with quality. Gold metal vanity cases were introduced for the solid mascara and, in 1936, a new cream mascara was introduced in dainty zipper bags. The liquid mascara seems to have disappeared from the product line at this time.

See also: Liquid and Cream Mascara

These product and packaging upgrades combined with the more sober advertising helped make Maybelline products more acceptable to middle America and the department stores in which many of them made their cosmetic purchases. Given that the 1934 cosmetic survey by ‘Woman’s Home Companion’ did not include eyeshadow, mascara and eye pencil because they were not considered important to their readers, anything that fostered sales to middle America would be to the company’s benefit.

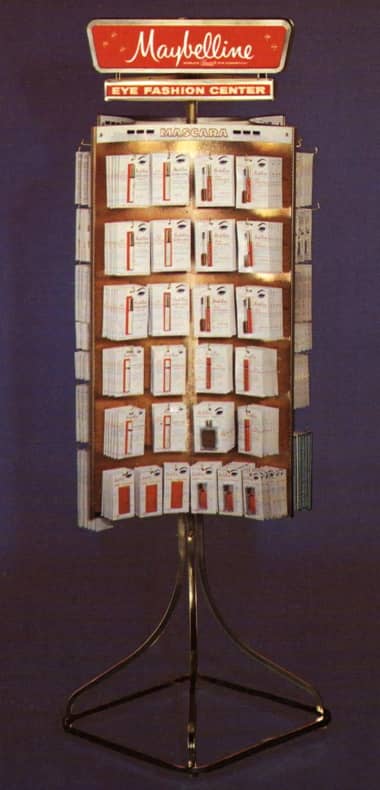

Maybelline’s fortunes dramatically improved when Harold (Rags) Ragland joined the company in 1933 and assumed control of sales and promotion. Under his more professional direction the company closed down the mail-order business, fixed many of its distribution problems, and opened up new avenues for sales through chain and department stores. Ragland also made the ten-cent ‘purse size’ mascara more widely available and introduced a new form of display card that could be hung prominently to attract a customer’s attention. The original cards used an image of the Maybell Girl but, in 1936, these were replaced with a more contemporary image, thereby closing the last symbolic link with the old Maybell Laboratories.

Above: One of the original display cards introduced by Harold (Rags) Ragland. The eye shadow product is missing from the card.

By 1934, the cash flow of the company was strong enough to allow Lyle to start buying up other mascara businesses as they came on the market, thereby solidifying Maybelline’s dominance in eye make-up in the American market. The 1930s also saw Maybelline expand into Canada and Europe (Williams & Youngs, 2010, p. 260). South America was added after the war and other countries followed giving Maybelline a global reach. At home, there was increased competition from the majors, but figures indicate that Maybelline still had about 75% of the American mascara market in 1947.

Packaging and distribution

The size of the company facilities on North Ridge Avenue were not large. This was possible because the company did not make any products themselves but rather sourced all of their products from private-label manufacturers. The cake mascara had originally been made by Maybelline but had been spun off as a separate company, De Luxe Mascara, in 1933. This meant that the North Ridge Avenue site only had to have space for packaging, distribution and administration.

This was still the case in the 1960s. Although some products were put together using machines, most Maybelline products were assembled by hand before being shipped out by truck.

Above: A Maybelline truck.

An attempt was made to bring manufacturing in-house in the later part of the 1950s. The company hired a cosmetic chemist named Julius Wagman to formulate and refine its Magic Mascara (1958) but operations were shut down by a Chicago fire inspector and once again manufacturing went private-label, this time by the Munk Chemical Company. Munk would go on to supply Maybelline with the materials for many of its later products.

Other suppliers included Avon Products who supplied Maybelline with its Sable Brown Cream Mascara in all sizes; the Anchor Brush Company, who provided brushes and plastic mouldings; the Chicago printer, Edwards and Deutsch, who produced the white Maybelline packaging cards; and Plastofilm, Inc. who made all the thermoformed blisters that were attached to the packaging cards.

Corporatisation and sale

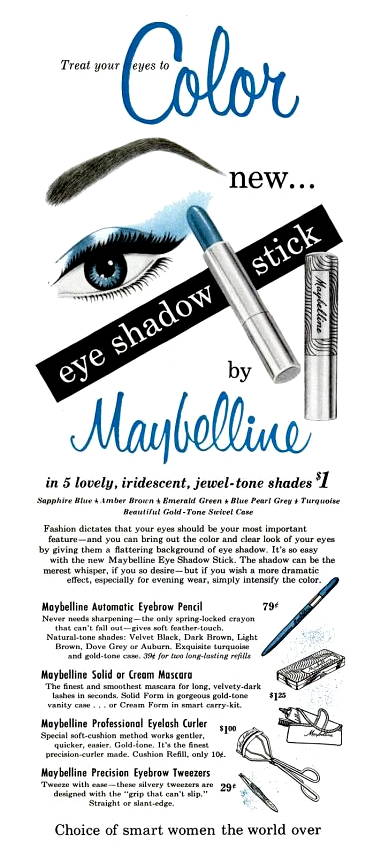

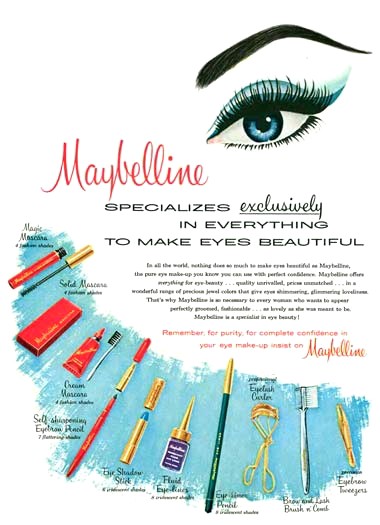

After its incorporation in 1954, the company saw two decades of continuous growth with sales reaching US$25 million in 1966 (Williams & Young, 2010, p. 304). During this time the company remained firmly fixed on eye products, including mascara, eyeliner, eyeshadow, eyebrow pencils, eyelash curlers and eyebrow tweezers.

In 1958, following Helena Rubinstein’s introduction of the Mascara-matic, Maybelline introduced its own version, the previously mentioned Magic Mascara, which used a brush applicator rather than a grooved metal wand, the first company that I know of to do so.

Also see: Automatic Mascara

Magic Mascara came in Velvet Black, Royal blue, Jade Green and Sable Brown shades.

Also see the booklet: Color Chart and Shade Selector

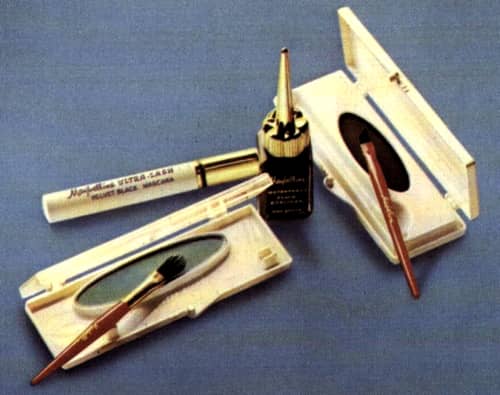

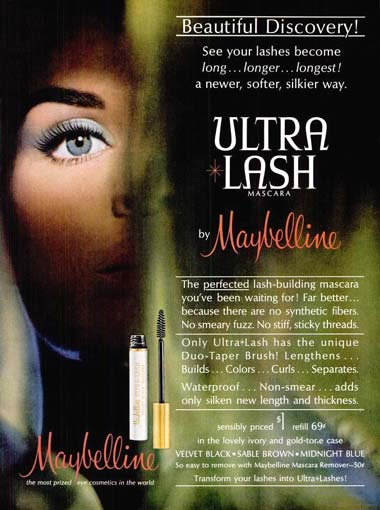

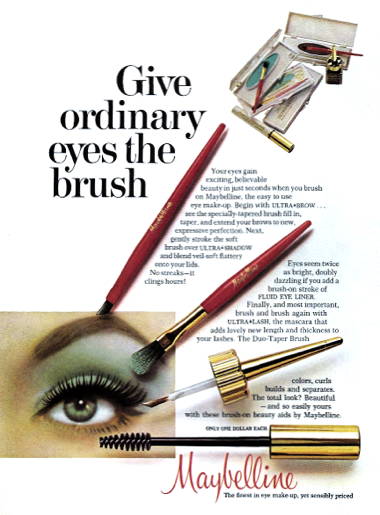

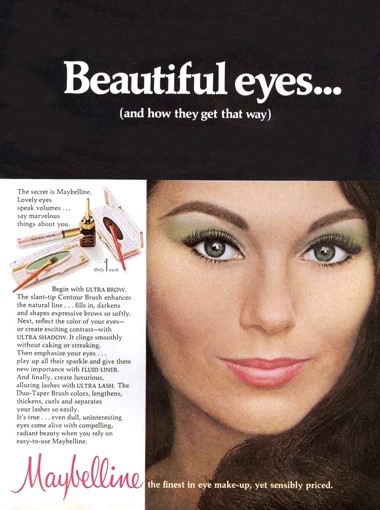

In 1963, Maybelline followed Magic Mascara with Ultra-Lash Mascara, the first in the Ultra line which would later include Ultra-Brow, Ultra-Liner and Ultra-Shadow.

Above: 1967 Maybelline Ultra-Lash, Liquid Eyeliner, Ultra-Brow, and Ultra-Shadow.

Sale

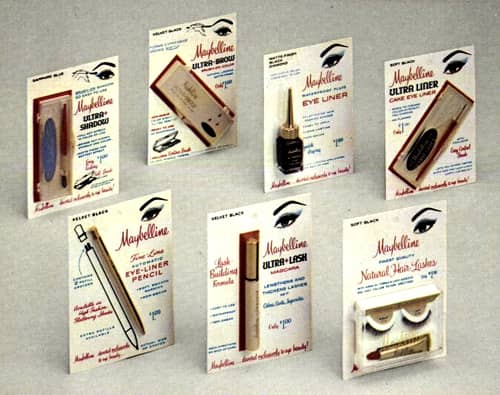

In 1967, Tom Lyle reached the age of seventy and was ready to sell. After turning down bids by Revlon and Schick, he sold the company to Plough in December, 1967 for US$136 million in cash and stock. Plough immediately began a program of expansion. It increased the Maybelline sales force from 44 to 79, took over much of the manufacturing of Maybelline products previously done by private providers, and introduced new products.

Above: 1968 Maybelline Ultra-Shadow, Ultra-Brow, Waterproof Fluid Eye Liner, Ultra-Liner Cake Eye Liner, Fine Line Automatic Eye-Liner Pencil, Ultra-Lash, and Natural Hair Lashes in blister packs.

The business stayed as Maybelline through the 1971 Plough-Schering merger and its sale to the Wasserstein Perella investor group but was renamed Maybelline New York in 2001 by its current owners L’Oréal, USA.

Timeline

| 1915 | Maybell Laboratories founded to make Lash-Brow-Ine. |

| 1916 | Advertising in Photoplay magazine begins. |

| 1917 | First real model used in advertising. New Products: Maybelline cake, eyelash and eyebrow make-up. |

| 1918 | Direct sale and distribution of products begins. |

| 1923 | Maybell Laboratories renamed Maybelline. |

| 1924 | Maybelline moves to new headquarters at 5900 North Ridge Avenue, Chicago. |

| 1925 | New Products: Waterproof Liquid Maybelline eye make-up. |

| 1929 | New Products: Eyebrow pencils (black and brown) and eyeshadow (blue, black, brown and green). |

| 1930 | Violet colour added to eyeshadows. |

| 1931 | Cake eyelash darkener reformulated. |

| 1932 | New Products: 10-cent product for drug and variety stores. |

| 1933 | Harold (Rags) Ragland joins the company. Maybelline begins to be sold direct to stores outside of the Chicago area. Mail-order starts to be closed down. First use of the word mascara in Maybelline advertising. The mascara manufacturing equipment sold to brother-in-law Tom Hewes, who establishes the De Luxe Mascara Company to make cake mascara for Maybelline. |

| 1934 | Blue colour added to mascara. The Maybelline Hour radio show starts on WFNT Chicago. |

| 1936 | New Products: Cream Mascara in a waterproof zipper case. |

| 1951 | First television advertising by Maybelline. New Products: Emerald Green mascara. |

| 1954 | Maybelline incorporates. New Products: Automatic Eyebrow and Eyeliner Pencil. |

| 1955 | New Products: Antiwrinkle Eye Cream (withdrawn the following year). |

| 1958 | New Products: Magic Mascara with a spiral brush. |

| 1961 | New Products: Fluid Eye Liner. |

| 1963 | New Products: Ultra-Lash mascara. |

| 1967 | Maybelline acquired by Plough. New Products: Natural Hair Lashes. |

| 1968 | Maybelline distribution through Plough regional warehouses begun. New Products: Frosty Whites, eyeshadow and eyeliner; and Ultra Liner pressed cake eyeliner. |

| 1969 | Plough begins manufacturing Maybelline products in a new laboratory in Memphis. New Products: Demi-Lashes, false eyelashes; Professional Eye Liner Brush; and Blooming Colors, an eye shadow palette. |

| 1970 | New Products: Moonstar Fashion Lashes. |

| 1971 | Plough merges with Schering to form Schering-Plough. New Products: Great Lash, a water-based mascara. |

| 1972 | British Maybelline sales force created taking over from Richards & Appleby. |

| 1974 | New Products: Fresh & Lovely Moisture Lip Color, Lip Shine Glosser and Fingertip Blushers; Ultra Velvet and Ultra Frost eye shadows; and Look Natural comb-on mascara. |

| 1977 | New Products: Fresh Lash mascara; and Styler-Pencils for eyes and lips. |

| 1983 | New Products: Shine Free Oil Control make-up line featuring non-comedogenic formulas. |

| 1990 | Maybelline acquired by Wasserstein Perella & Co. |

| 1991 | “Maybe she’s born with it. Maybe it’s Maybelline” advertising tagline created. |

| 1996 | Maybelline acquired by L’Oréal USA. |

| 2001 | Maybelline becomes Maybelline New York. |

First Posted: 8th November 2010

Last Update: 21st September 2022

Sources

Jones, G. (2010). Beauty imagined: A history of the global beauty industry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

deNavarre, M. G. (1941). The chemistry and manufacture of cosmetics. Boston: D Van Nostrand Company.

Phillips, M. C. (1934). Skin deep: The truth about beauty aids. New York: Garden City Publishing.

Poucher, W. A. (1932). Perfumes, cosmetics and soaps, Vols. 1-2 (4th ed.). London: Chapman and Hall.

Sharrie Williams. (2011, September). Retrieved September 3, 2011, from http://www.maybellinebook.com/

Williams, S., & Youngs, B. (2010). The Maybelline story and the spirited family dynasty behind it. Florida: Bettie Youngs Books Publishing.

Thomas Lyle Williams [1896-1976].

1916 Maybell Laboratories Lash-Brow-Ine. One of the first advertisements for the product.

1919 Maybell Laboratories Color-ine. One of the company’s early failures.

1920 Maybell Laboratories Lash-Brow-Ine with the Maybell Girl featured prominently on the box and aluminium container.

Maybelline liquid and cake mascara.

1926 Actress Viola Dana endorsing Maybelline.

1929 Maybelline Eyelash Beautifier.

1930 Maybelline advertisement for eye shadow (in blue, brown, black and green shades) and eyebrow pencil (in black and brown shades). Maybelline (cake and liquid) is now referred to as an eyelash darkener.

1933 Maybelline Eyelash Darkener. The advertising copy calls it ‘The perfect mascara’ an early use by Maybelline of the term forced on them by the Lash Lure scandal.

1936 Maybelline Cream Mascara and other items attached to redesigned product cards introduced by Rags Ragland. These would be later replaced with white cards with the classic Maybelline eye in the corner.

1937 Maybelline products in new packaging. Note the more sober tone and the ‘Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval’. The cream mascara with its zipper bag had been introduced the previous year.

1937 Maybelline ‘before and after’ advertisement. The model used is not a movie star.

1949 Maybelline Cake Mascara, Cream Mascara, Eyebrow Pencil and Eye Shadow. The ‘Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval’ has disappeared.

1952 Maybelline ‘before and after’ advertisement. The eye make-up is more severe, sophisticated and glamourous than that of the the 1930s but the message has not altered much in fifteen years.

1956 Maybelline Eyeshadow Stick.

1959 Maybelline Magic Mascara. Maybelline’s first automatic mascara and the first automatic to use a spiral brush.

1960 Maybelline Magic Mascara, Solid Mascara and Cream Mascara (each in 4 shades); Self-sharpening Eyebrow Pencil (7 shades); Eyeshadow Stick (6 shades); Fluid Eye-liner (8 shades); Eyeliner Pencil (8 shades); Eyelash Curler; Brow and Lash Brush ’n Comb, and Eyebrow Tweezers. Solid and cream mascara was soon to disappear from the Maybelline range.

1964 Maybelline Ultra-Lash Mascara in Velvet Black, Sable Brown and Midnight Blue. Note the change in the brush shape.

1966 Maybelline Ultra-Brow, Ultra-Shadow, Fluid Eyeliner and Ultra-Lash mascara.

1967 Maybelline Eye Fashion Center self-service stand.

1968 Maybelline Eye Make-up.

1969 Customer trying on Maybelline at a cosmetic counter.

1972 Maybelline trade advertisement announcing the formation of a British sales force after the Plough-Schering merger.

1978 Maybelline Nail Color.