Klytia

Continued onto: Klytia (1930-1945)

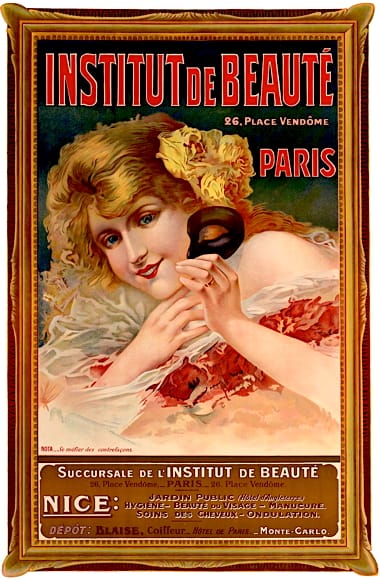

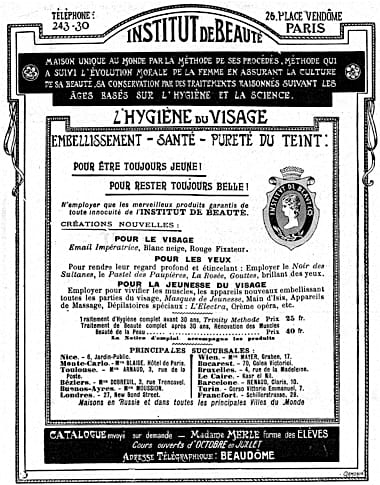

Klytia is often said to have been founded by Marie Valentin Le Brun at 26 Place Vendôme, Paris in 1895, becoming the first Institut de Beauté established in France. However, things are not that clear cut. Address records show that the salon opened its doors at 26 Place Vendôme in 1899, not 1895, and that Victor François Merle [b.1856] was also one of its owners.

Above: c.1910 Looking down the Rue de la Paix from the Place Vendôme. The Hôtel de Boullongne building at 23 Place Vendôme (left) and the Hôtel de Nocé building at 26 Place Vendôme (right).

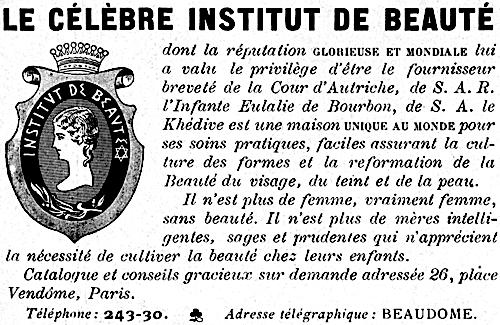

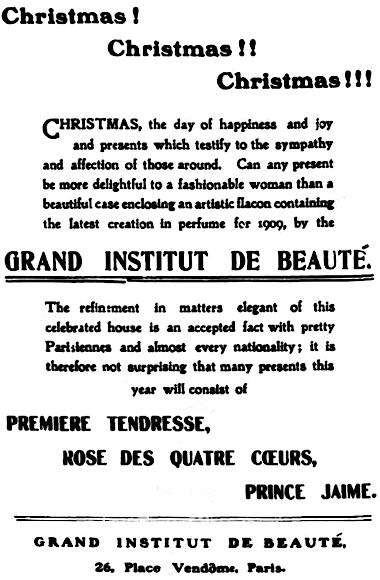

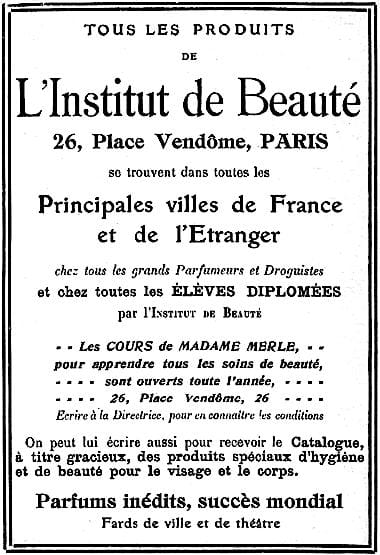

When Le Brun and Merle opened their salon in 1899 they named it the Institut de Beauté not Klytia and, as far as I can tell, they were the first to use that title. However, a 1907 court case saw them lose the exclusive right to use ‘institut de beauté’ as a trademark and it became a generic term applied a beauty salon or business in France; e.g., Institut de Beauté Castiglione. So, although Klytia was the first to use the institut de beauté name, this should not be interpreted as it being the first beauty business to open in France.

After losing the court case, the Institut de Beauté went through a series of name changes as its owners tried to distinguish it from the growing number of other beauty institutes. Starting with the Célèbre Institut de Beauté, it became the Institut de Beauté Klytia, before becoming the Klytia Institut de Beauté. I will generally refer to it simply as Klytia from here on.

Above: Institut de Beauté trademarks. Left 1910; right 1923. Note the Star of David on both shields. Marie Valentin Le Brun appears to have been Catholic so this suggests that Victor Merle was a Jew.

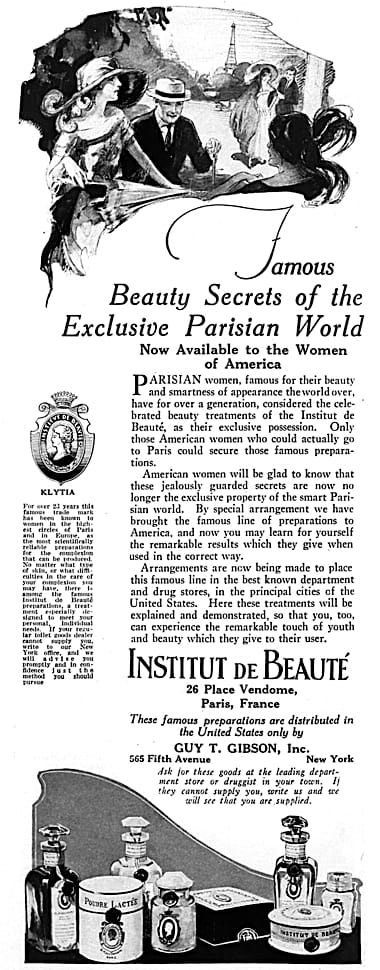

Although Klytia was not the first beauty business to open in France its importance should not be overlooked. Anyone visiting Paris in the early part of the twentieth century looking for a beauty treatment would have considered a visit to the salon in the Place Vendôme an essential stop. I have no doubt that Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden would have booked treatments there when they first came to Paris.

See also: Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden

Marie Valentin Le Brun

Marie Valentin Le Brun was born Elise Marie Le Brun in 1860, the daughter of Julien Joseph Le Brun and Victorine Elsa Prevel. She added Valentin to her name when she married Jules Ernest Valentin [1855-1891] in 1877, becoming Madame Merle following her marriage to Victor Merle in April, 1901.

Marie Le Brun’s earlier marriage to Jules Valentin produced at least two children – Juliette Louise Valentin [b.1878] and Henriette Elise Marie Valentin [b.1885]. Both women followed their mother into the beauty industry. Juliette and her husband Charles Adolph Keicher founded the Institut de Beauté Keicher-Valentin, later shortened to the Institut de Beauté Keva. Her younger sister, Henriette, who married Antoine Marie Font, became the proprietor of another French beauty business, the Université de Beauté Cédib.

I have been unable to find any business records for Marie Valentin Le Brun or Victor Merle before they formed the Société Merle et Valentin in February, 1899 and opened the salon on the Place Vendôme. However, this does not invalidate the earlier date. Marie Valentin Le Brun may have gone into the beauty business in 1895 before joining forces with Victor Merle who appears to have been a hairdresser.

Klytia claimed to have opened a laboratory in Place Vendôme in 1895 before moving manufacturing to 45 Rue du Marché, Neuilly-sur-Seine in 1898. I have no evidence that a laboratory was opened in the Place Vendôme in 1895 and have been unable to find anything corroborating the Neuilly-sur-Seine address of 1898. However, given the wide range of products Klytia had available in 1899 it does not sound unreasonable that manufacturing had started a year earlier.

The Société Merle et Valentin was dissolved in May, 1901 following Le Brun’s marriage to Merle in April. I have no records of any new business entity being established by either of them until the late 1920s. During this time Victor Merle is listed as the proprietor of the Institut de Beauté with Marie Valentin Le Brun credited as its founder and salon directrice. I note that Le Brun is often omitted from Klytia advertisements which suggests that Merle may have been the biggest financial contributor to the business.

Expansion

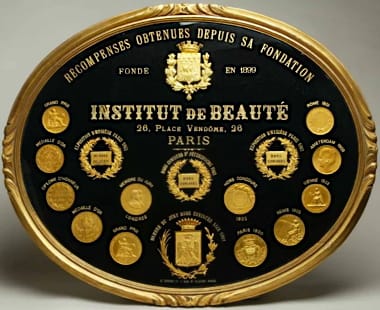

Soon after it opened, Klytia began collecting awards for its products at exhibitions across Europe, including Paris (1900), Nice, and Rome (1901), Paris, London, Vienna, and Amsterdam (1902), and Saint Petersburg (1903).

Above: 1903 Awards achieved by the Institut de Beauté.

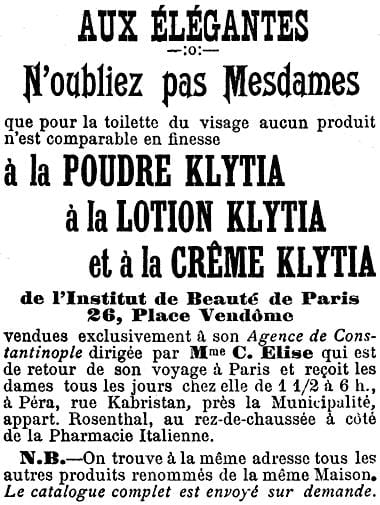

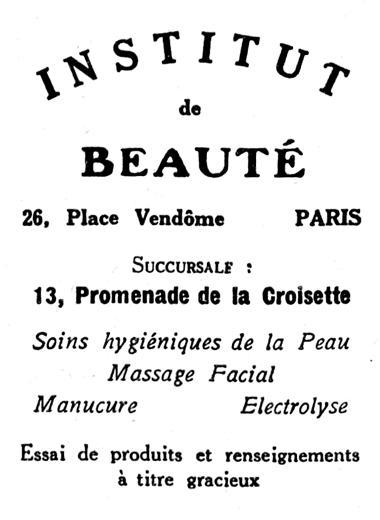

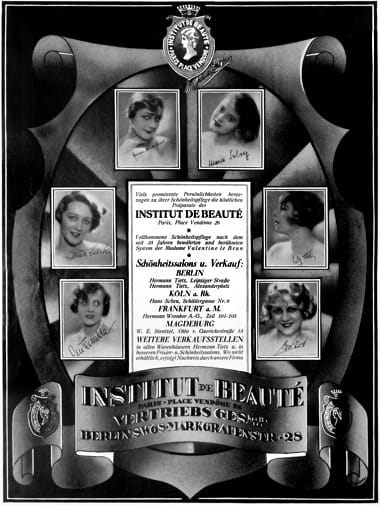

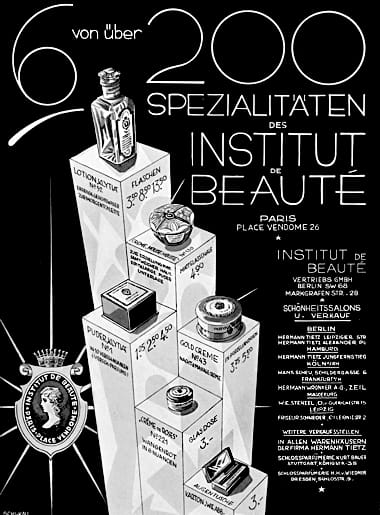

The prestige from these awards helped Klytia establish outlets across Europe and elsewhere. By 1904, its products were available in major capitals around in the Western world including London, Vienna, Berlin, St. Petersburg, Madrid, Rome, and New York, with Buenos Aires added by 1907, and Alexandria, Cairo, Frankfurt, Florence, Turin, Bucharest, Constantinople, and Geneva by 1909. Klytia also opened a number of additional salons starting with Nice followed by Vichy and Monte-Carlo.

The First World War cut off many of the Institut’s markets from Paris forcing some outlets to close permanently while others reopened after 1918. Things got better in the 1920s and, by the end of the decade, Klytia was also avialable in cities such as Athens, Casablanca, Prague, Riga, Copenhagen, Havana, Lima, Rio de Janeiro, and Shanghai.

Divorce

Valentin Le Brun and Victor Merle divorced in 1920. The business was put up for auction in 1925 with Valentin Le Brun making the winning bid with the handover finalised in 1926. The auction included the salon at 26 Place Vendôme, the factory at 45 Rue du Marché Neuilly-sur-Seine, the warehouses at 18 Philippe-le-Boucher Avenue and the salons in Nice, Vichy, and Monte-Carlo. Following the sale, the business became Les Établissements Klytia which suggest that the new business entity was created serve the interests of other investors. However, I do not have any records of its foundation.

In 1926, a new, larger factory was opened at 136 Rue Victor-Hugo, Levallois-Perret, with previous factory at Neuilly-sur-Seine vacated by 1928. By then, the salon in Vichy had also closed down but another had been opened in Cannes.

In 1929, the Klytia Corporation (capital, US$100,000), was founded in New York taking over from Guy T. Gibson, Inc. which had been the sole importer of Klytia’s products into the United States until then. Albert Raimon, former chemist and perfumer for the French company, was sent over to act as the company president with Alleen Fayye, previously with Helena Rubinstein, employed as its vice-president. Offices were set up at 545 Fifth Avenue, New York, in what use to be the Hotel Lorraine, and plans were made to open a salon there at a later date.

The French business was also restructured in 1929 becoming the Société Anonyme des Établissements Klytia (capital ₣3 million). It controlled Klytia’s world-wide activities including the factories in London and Milan, with the one exception being the business in the United States.

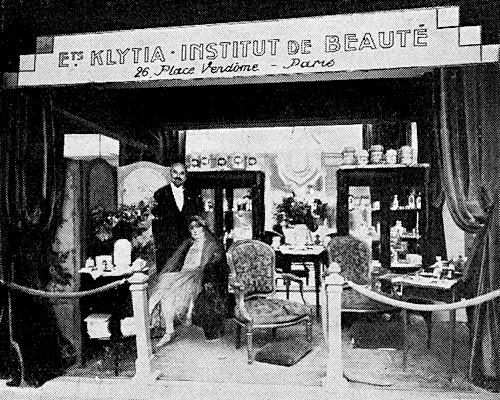

Salon

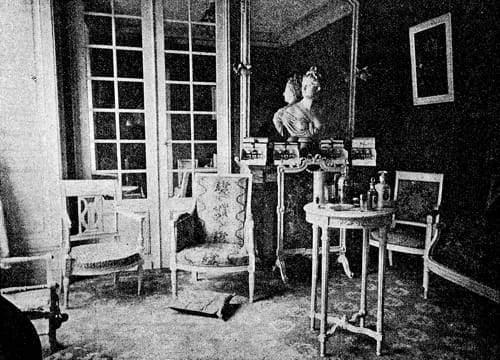

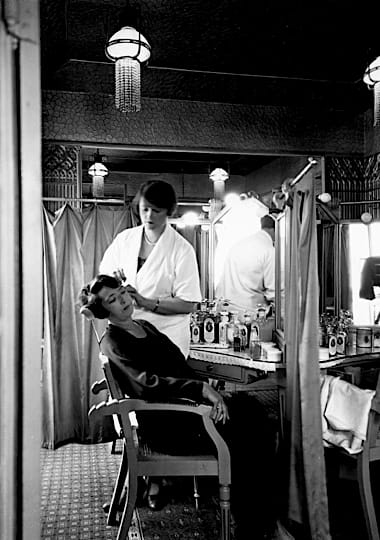

Photographs of the salon at 23 Place Vendôme show that it was well appointed when it opened, becoming more luxurious in later years.

Above: 1903 Institut de Beauté: Reception.

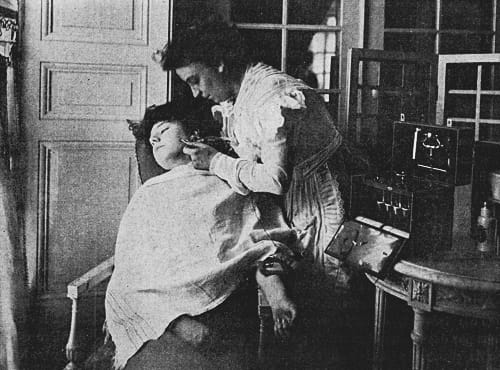

Above: 1912 Institut de Beauté: treatment room.

Above: c.1928 Institut de Beauté: reception.

Above: c.1928 Institut de Beauté: treatment cubicle.

Salon treatments

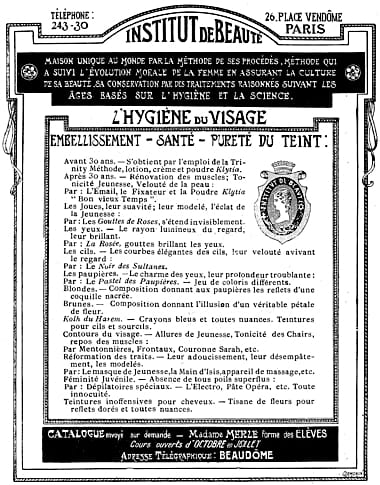

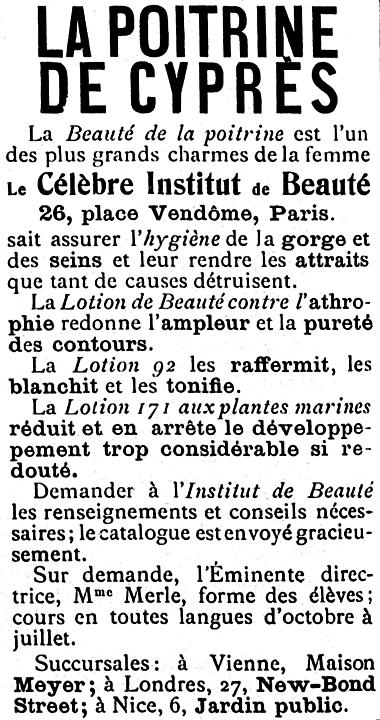

Klytia provided clients with a wide variety of treatments. As well as face and body treatments the salon services included hair dressing such as waving, adding hair pieces, hair dying, and manicures. It also helped clients with other problems such as reducing their weight or improving their bust size.

Above: c.1928 Manicure station.

Most of Klytia’s clientele were mature women with the necessary means to make regular visits. Klytia’s stated aim with regard to skin-care was to cultivate and preserve a client’s natural beauty. This meant reducing or reversing the effects of ageing and removing skin blemishes like pimples and freckles. Treatments were promoted as hygienic, scientific, and rational and combined a range of physical therapies with an assortment of cosmetics. Women who were unable to attend the salon in person could replicate many of the salon treatments by buying the necessary cosmetics and devices such as vaporisers/pulverisers from a suitable outlet or through mail order.

Above: 1902 Pulverisation treatment possibly using something like Lotion Spéciale No, 179, a balsamic antiseptic. The woman in the background looks to be Madame Merle.

See also: Vaporisers (Steamers & Atomisers)

Klytia thought it was better to cure problems rather than cover them with make-up. Treatments combined a good diet and massage with astringents and other efficacious skin creams and lotions. Keeping the skin clean was essential and soaps and/or other cleansers were used with powders added to water to make it ‘softer’ and/or increase its effectiveness.

Massage

Massage was considered to be the most important of the physical therapies. It was believed to be able to remodel many aspects of the face including problems such as wrinkles and double chins, an idea held by many in the beauty industry at the time. The benefits of massage extended to the body where it was employed in weight reduction and weight gain treatments depending on the type of massage used.

Also see: Massage, Wrinkles and Double Chins

Klytia thought mechanical aids were needed for women to achieve anything close to the results of a salon massage at home. These aids included mechanical massagers and electrical vibratory massagers when they became available. Mechanical massagers included an assortment of rollers and a small, hand-held massager made from porcelain called the Main d’Isis (Hand of Isis) No. 2141.

Patting

Patting the face when applying astringents or other skin-care cosmetics was regarded as very beneficial. It brought blood to the skin which brought in nutrients and removed wastes. Women could mimic the patting treatments used in the salon with one of the Klytia’s Claquettes, a type of patter.

Above: Klytia Claquette No. 2210. This is the smaller version. The covers would be soaked in a liquid astringent before being fitted to the metal base.

See also: Patters

Strapping

Along with massage, strapping and/or bandaging was a very common salon practice. The range of straps and bandages sold by Klytia for the face, chin and body is one of the largest I have seen and covered every contingency. Also available for sale were devices to correct problems such as protruding ears or less than aquiline noses.

A small range of radio-active straps was later added to provide the body and face with the ‘beneficial’ effects of what, I assume, was radium. To distinguish them from other straps they were dyed red. Hopefully, given its high price, the levels of radium used in these masks and straps was not high enough to be very dangerous.

Skinning and surgery

Deep-seated problems such as acne or smallpox scars were treated by Klytia with skin peels, using a procedure sometimes known as face skinning, now generally considered too dangerous to be carried out by a lay person.

See also: Face Skinning

Klytia provided clients with more drastic options after it opened a cosmetic surgery clinic staffed with specialist surgeons. Surgical procedures included the removal of crow’s feet, wrinkles, double chins, and bags under the eyes, nose and ear corrections, breast reductions and abdominal tightening. Prices varied but generally started at 200 francs per day with some operations requiring patients to recuperate in rooms set aside in the salon. Klytia was not alone in providing clients with these more radical procedures. The Université de Beauté Cédib also provided clients with cosmetic surgery treatments and similar procedures were available in other large Western cities for those who could afford it and were prepared to take the risk.

See also: Woodbury

Electrical treatments

The only electrical procedures that I know Klytia conducted in the salon through to 1930 were high-frequency and electrolysis. High-frequency could be used for scalp problems such as dandruff and thinning hair and/or for facial treatments such as pimples and acne. Electrolysis was normally used for permanent hair removal and for removing skin blemishes such as telangiectasia (spider veins). As with other salon treatments, women could purchase machines from Klytia to continue these treatments at home.

Above: 1903 electrolysis treatment using battery power.

See also: High-Frequency Treatments and Electrolysis

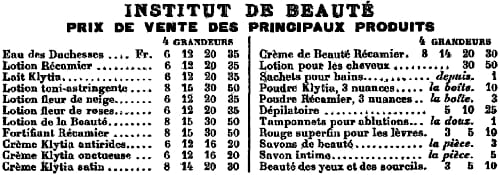

Preparations

Klytia’s early range included skin-care cosmetics, soaps, hair products, a depilatory, toothpastes, and a few items of make-up. Products were often referred to by number rather than name, a French tradition, and this extended to make-up shades which were also often given sequential numbers or letters of the alphabet as well as, or instead of names.

Above: 1899 Some items available from the Institut de Beauté.

Some products were named for Klytia, a water nymph in Greek mythology while others invoked famous women. For example, Lotion, Fortificant, Crème de Beauté, and Poudre Récamier all refer to Juliette Récamier [1777-1849], a well-known, nineteenth-century French beauty. Some later products continued this practice. For example, Poudre, Lait, and Lotion Eulalia are named after Infanta Eulalia [1864-1958], the Duchess of Galliera, while Crème, and Poudre Djavidan are referring to Javidan Hanim [1877-1968], also known as Djavidan of Egypt. Both women were claimed by Klytia as clients.

Above: 1913 Le Célèbre Institut de Beauté.

Skin-care

The first skin-care cosmetics offered by Klytia included a wide range of waters, creams and lotions with allowances made for age and skin type.

An examination of the recommended treatment routines from 1906 for women older than 25 reveals that they all followed a morning regime of cleansing, lotion, and foundation before finishing with Poudre Klytia No. 1. Even very young women finished with Poudre Klytia in the morning as powder was considered to be a skin protective.

Aged 18-25

Oily skin:

Night: Lotion Klytia No. 52.

Poudre Klytia No. 1.

Dry skin:

Night: Lotion No. 86.

Morning: Poudre Klytia No. 1.

Aged 25-35

Oily skin:

Night: Crème Klytia Antiride No. 54.

Morning: Lotion Klytia No. 52, Crème de Beauté No. 24, and Poudre Klytia No. 1.

Dry skin:

Night: Crème Klytia Antiride No. 54.

Morning: Lotion No. 86, Crème Léntive au Suc de Laitue No. 177, and Poudre Klytia No. 1.

Aged 35-50

Oily skin:

Night: Lotion Tonic Champagne No. 173 and Crème Klytia Antiride No. 54.

Morning: Lotion Klytia No. 52, Crème de Beauté No. 24, and Poudre Klytia No. 1.

Dry skin:

Night: Eau des Duchesses No. 12, and Crème Klytia Antiride No. 54.

Morning: Lotion No. 86, Crème Klytia Satin No. 118, and Poudre Klytia No. 1.

Aged over 50

Oily skin:

Night: Crème Antiride No. 122.

Morning: Lotion Klytia No. 52, and Poudre Klytia No. 1.

Dry skin:

Night: Crème Antiride No. 122.

Morning: Lotion No. 86, and Poudre Klytia No. 1.

Specialist products were also available for specific skin problems. For example, girls and young women with freckles could treat them with Lotion des Circassiennes No. 4 while those with pimples and acne were recommended to use Lait Klytia No. 70.

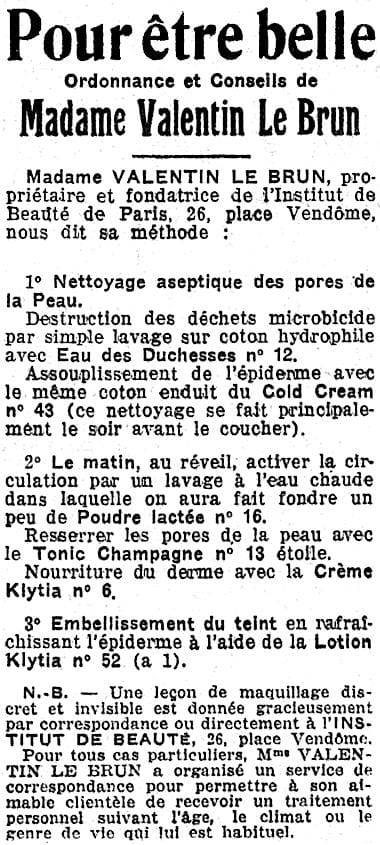

Klytia provided clients with instructions on how best to use its skin-care cosmetics. An early example is given below:

1. Dissolve in a basin of half a litre of water à small spoonful of Poudre Lactée.

2. Use a little cushion of absorbent cotton, instead of the hand or a cloth (sponges forever anathema). We call this little cushion a “tampon” and we use it at the Institut de Beauté about the size of a common powder-puff. Dip this “tampon” in the prepared water and pat the face till it is moistened and the skin has thoroughly imbibed the preparation. It is an art to do this properly.

3. Without drying the face, take up on the damp “tampon” a little of the Crème Klytia, to nourish and soften the skin. By soft little circular movements, upward and outward, cause this cream to penetrate the skin.

4. Still, without drying the skin, and making use of the same “tampon,” impregnated now with the Lotion Klytia tap lightly every portion of the face and features, ending with a slight friction in order to impregnate the skin—the epidermis—with this refreshing and beneficent skin tonic.

5. In order to obtain the whiteness and suavity of tone, after this absolute hygienic care, the Institut de Beauté recommends particularly its wonderful cream “Suc de Laitue.” This cream is applied also with the same “tampon,” constantly wet, taking care that the skin also has been kept wet with the Crème Klytia, that is to say, soon after using the Lotion Klytia, without wiping the face, press the tube “Crème au Sue de Laitue” on the “tampon” slightly, so as to take in a small quantity of the cream, and apply this to the skin with the same care and the same circular motions as the “Crème Klytia.”

6. With the same “tampon,” constantly moist, in the order indicated, go over the face, assuring yourself of uniform treatment. Then, with a soft, fine linen cloth, wipe the face in all its contours, and powder with the “Poudre Klytia”—superior to all others, impalpable and invisible.(Institut de Beauté advertisement, 1906)

Women looking for a simpler skin-care program could follow Klytia’s Trinité-Méthode which combined Crème Klytia, Lotion Klytia, and Poudre Klytia.

Trinity-Method

Hygiene, health, beauty, radiance, youth

Crème Klytia anti-wrinkle cream, through its nutrition and invigorating richness, it erases wrinkles, restores life, elasticity and youth to the epidermis.

Lotion Klytia’s softening and refreshing properties, maintains and ensures the beauty and sweetness of the complexion.

Poudre Klytia, hygienic and beneficial, it is without rival.(Modified translation, Institut de Beauté advertisement, 1907)

Many of Klytia’s early skin-care lines remained in the inventory for decades but some did not. After Victor Merle lost an appeal against the Chambre Syndicale des Pharmaciens de la Seine in 1912 the court forced him to remove Fortifiant Récamier and Lotion No. 101 from Klytia’s inventory on the grounds that curative claims had been made for the products. This made them medicines in the eyes of the court, substances that could only be made and sold by a pharmacist. Fortifiant Récamier also worried the pharmacists because it contained l’eau de laurier-cerise (cherry laurel water) known to contain hydrogen cyanide. Lotion 101, an eye drop, also contained a toxic substance, alcaloïde mydriatique (mydriatic alkaloid), which was used to dilate the pupil of the eye.

Later developments

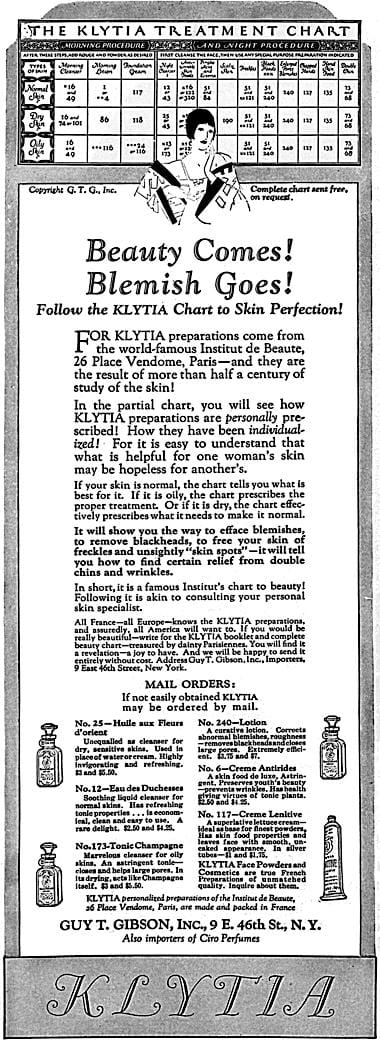

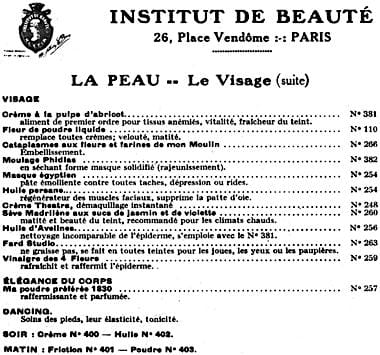

By the late 1920s, the range of skin-care cosmetics offered by Klytia had become very extensive, perhaps confusingly so. Some of the reason for the large variety of products seems to stem from the numerous factors Klytia took into account when developing its treatment regimes.

The treatment of facial skin is very complex and can be multiplied endlessly depending on the complexion, the temperament of each subject and the quality of their skin; the climate in which they live; even on the light in which they appear, or their state of mind.

(Modified translation from Klytia, c.1927, p. 14)

Some of these, such as skin type, are still in use today while others, such as temperament, appear rather strange to modern eyes.

Temperament

When Klytia referred to ‘temperament’ it was referencing a physical rather than a psychological state of being which appears to have echos from the older idea of body humours. Temperament in this sense has associations with temperature so Klytia used the client’s temperament to determined the best water temperature to use when washing the face.

If your primordial temperament is:

1. Lymphatic, anaemic, pale, use cold water which is stimulating and toning;

2. Neutral, nervous, delicate, hypersensitive, use lukewarm water which is softening and refreshing;

3. Congestive, use hot water which is calming and decongesting;

4. Bilious, there are two possibilities. First, if the complexion is pale and the skin is dry, use cold water; second, if the skin is oily with open pores, use hot water.(Modified from Klytia, c.1927, p. 14)

See also: The Complexion

Skin types

In the 1920s, Klytia recognised four main skin types – Oily, Dry, Neutral, and Delicate/Hypersensitive. These were linked to the client’s temperament which produced some anomalous results by today’s standards. For example, the Delicate/Hypersensitive skin type included a number of skin conditions we would not normally consider to be associated with hypersensitivity. Similarly, the Neutral skin type is not what were would now think of as Normal as it included individuals who might now be regarded as having combination skin.

Oily Skin: Bloody or congestive subjects individuals, those with a shiny epidermis or dilated pores, with lymphatic temperaments, or with thick, distended and shiny skin.

Dry Skin: Individuals with bilious temperaments, the nervous, the anaemic or those with weakened and relaxed muscles.

Neutral Skin: Subjects that belong neither to the first nor to the second category, but which can be classified as half part oily, half part dry or have healthy skin with some defects.

Delicate or Hypersensitive Skin: Those who suffer from an imbalance of circulation and are afflicted either with rosacea, redness, acne, blackheads or other skin defects.(Modified translation from Klytia, c.1927, p. 19)

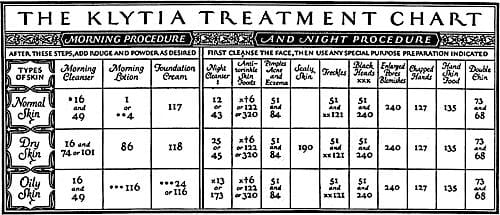

This classification system was not fixed and we sometimes find Klytia referring to oily, dry and normal skin types, a situation that was probably due to the increasing influence of American beauty businesses.

Skin-care routine

Klytia’s basic skin-care routine for the late 1920s was on the more familiar ground of:

1. Le nettoyage de la peau (cleansing the skin);

2. La tonification des tissues musculaires (toning the muscles); and

3. L’embellissement du visage (beautifying the face).

As well as temperament and skin type the selection of suitable skin-care cosmetics also took other skin conditions and the time of the day into account. This resulted in Klytia producing a wider variety of skin-care cosmetics than many other beauty businesses at the time. The Guy T. Gibson corporation, which imported Klytia’s products into the United States, appears to have recognised that Klytia’s treatment regime needed simplification. Gibson kept the numbering system but offered a reduced range of suggestions for morning and evening routines based on the more conventional Normal, Oily, and Dry skin types with added suggestions for particular skin problems.

Above: 1925 Klytia treatment chart (USA).

Néoplastique

By the late 1920s, competition in the beauty business was very fierce and Klytia had to contend with a large number of new French establishments was well an increasing number of American companies with well appointed salons and novel treatment regimes. This may be why Klytia introduced a group of products it referred to as Néoplastique in 1927. This included included Huile Persane No. 254, Huile d’Avelines No. 256, Crème à la Pulpe d’Abricot No. 381 and Fleurs et Farines de Mon Moulin No. 266, and two masks, Moulage Phidias No. 382, and Masque Éyptien No. 383.

Looking at the range they appear to have been aimed at the Institut’s more mature clients with drier more wrinkled skin. Huile Persane (Persian oil) appears to have been a typical muscle oil of a type popularised by salons such as Eleanor Adair. Huile d’Avelines (Hazelnut oil) was used to clean the face and ready it for Crème à la Pulpe d’Abricot (Apricot pulp cream) a skin food, while Fleurs et Farines de Mon Moulin was used in acne treatments. Moulage Phidias may have been an astringent mask while Masque Éyptien looks to have included a whitening agent.

See also: Muscle oils and Skin Foods

Eyes

Like most salons of the time, Klytia sold a number of products to refresh and brighten the eyes, remove redness and dark circles. These could be applied as drops, in compresses, eye washes or added to the water during a pulveriser treatment.

Eyebrows and eyelashes also received attention. Eyebrows that were too think or misshapen could have hair removed with tweezers, threading, electrolysis or the depilatory paste Crème Opéra No. 67. If the eyebrow hairs were sparse, growth could be encouraged with Crème Pousse-Cils No. 115 and Lotion Pousse-Cils No. 31. Those that were too light in colour could be dyed with Pâte du Liban No. 183.

To obtain long, thick eyelashes, Klytia recommended trimming or singeing them periodically to improve their growth and, like the eyebrows, coating them with Crème Pousse-Cils No. 115 and Lotion Pousse-Cils No. 31.

Also see: Eyelash Growers

Depilatories

Klytia offered other ways to remove superfluous hair including a cream depilatory, Crème Opéra No. 67, for delicate areas such as the upper lip or eyebrows, and a powder depilatory, Poudre Rose No. 69, to be mixed up as a paste for use on the arms and legs. A third preparation, Lotion Épilatoire Progressive No. 105 was said to lighten hair and make it fall out. One hopes that it did not contain the toxic substance thallium acetate.

Klytia also sold two abrasive depilatories, Poudre des Mauresques No. 46 for downy hair and Épile-Ponce No. 85 for regular leg and arm hair. Both were rubbed over the skin with the previously mentioned Main d’Isis.

See also: Chemical Depilatories

Hands and nails

Klytia sold a number creams and lotions for the arms and hands as well as a number of products for improve the appearance of the nails including manicure kits and manicure implements.

Klytia relied primarily of abrasive polishes to improve the look of the nails and to give it shine but some products such as Rouge Rubis Liquide No. 94 may have contained a dye to make the nails look pinker.

In the late 1920s, Klytia appears to have added a nail polish, Beauté des Ongles No. 734. I do not know its original shade range but I suspect that it was colourless or a light pink. However, by the end of the 1930s the polish in came in Corail, Rosé, Rubis, and Clair Incolore. By then, Klytia had also added a nail polish remover, Dissolvent des Ongles No. 354. Given the shade range of Beauté des Ongles, I suspect that the colours were produced with dyes not pigments. This meant that the polish would have been transparent not opaque like the nail polishes that came to dominate after the Second World War.

See also: Nail Polishes/Enamels

Make-up

Initially, Klytia was very critical of make-up, considering that it covered up skin problems rather than fixing them. Despite this, it had at least two face powders in its inventory – Poudre Klytia No. 1 and Poudre Récamier, both coming in Rachel, Blanche, and Rose shades – a liquid rouge – Fleur de Roses No. 56 – and what looks to be a mascara – Beauté des Yeux et des Sourcils No. 229.

As mentioned earlier, Klytia considered powder to be an indispensable skin protectant and included it in all of its morning facial routines. Powder whitened the skin, evened out skin tones and made the skin look velvety while absorbing perspiration. Like others, Klytia insisted that its face powders neither obstructed or widened the skin’s pores or had any other adverse effect.

A lot of the odium associated with wearing make-up began disappearing after the First World War with France, particularly Paris, leading the way in its adoption. This led Klytia to add a full range of make-up to the 200 or so products in its inventory. Unfortunately, documentation on when these cosmetics were introduced is largely missing so the information below is largely from the late 1920s.

Like its skin-care range, Klytia’s make-up range was very extensive and had one of the widest shade ranges I have come across for that time, perhaps only exceeded by companies that specialised in stage and film make-up. Klytia did sell make-up to actors and actresses in the years before greasepaint became ubiquitous and had a few products that look to have been specifically developed for the theatrical and film trade such as Crème Theatra No. 248, a make-up remover, probably formulated as a cold cream.

Also see: Greasepaint

Foundations and powders

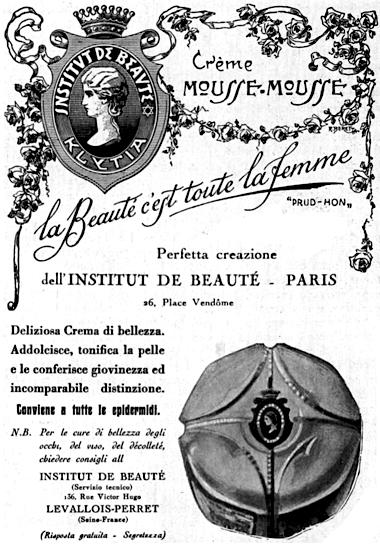

Klytia sold a wide variety of creams that could be used as a foundation for powder. These included Crème de Beauté No. 24, Crème Montespan No. 120, and Crème Mousse-Mousse No. 130 with a late addition being and Gloire des Crèmes No. 653. Some, such as Crème Klytia Satin No. 118, Crème au Suc de Concombre No. 127 and Crème Sport No. 64 came in tubes. However, as far as I can tell none of these foundations were tinted to match the overlaying face powder.

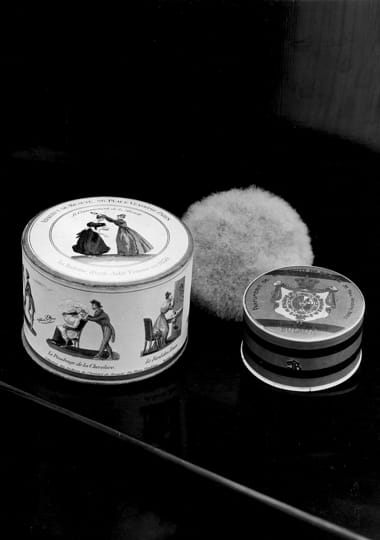

Of the two powders in Klytia’s original inventory, that I know of, only Poudre Klytia survived. It came in two forms – Poudre Klytia No. 1 for the face and Poudre Klytia No. 2 for the body probably differentiated by the fineness of the powder.

By the late 1920s, Poudre Klytia No. 1 and No. 2 came in a greatly expanded shade range – Blanc, Crème, Bise, Rose, Rachel, Chair Naturelle, Chair, Ocre, Mauresque, and Ocre Ému – scented with a wide variety of perfumes – Violette, Héliotrope, Fougère, Peau d’Espagne, Rose des Quatre-Cœurs Jasmin, Oeillet, Muguet, Chypre, and Bouquet Parfumé – as did Poudre du Nil No. 19 and Poudre de Riz des Artistes No. 35. How any one stocked all the permutations of shade and perfume is beyond me.

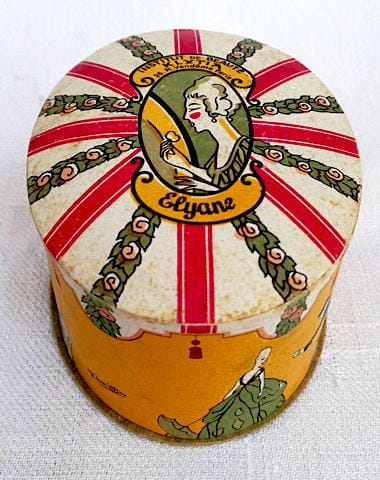

Other powders available by then included Poudre de Riz Eulalia No. 5, Poudre Djavidan No. 147, Poudre Nuage Cipaye No. 142, Poudre Elyane No. 238, and Poudre Le Bon Vieux Temps No. 38. Some like Poudre de Riz Eulalia and Poudre Elyane came in extensive shade ranges others less so. Some powders such as Poudre Elyane, Poudre de Riz Eulalia, and Le Bon Vieux Temps were also limited to a single fragrance with Poudre Porphyrisée Hygiénique No. 187 made fragrance free in Blanc, and Crème shades for women with perfume sensitive skins.

Included in this range was Ma Poudre Préféré 1830 No. 257 in Blanc, Crème, Chair, and Rose shades, a body powder with the perfume acting as a deodorant, and Poudre Aseptique Camphrée No. 208 in Blanc, and Crème shades containing camphor to help reduce inflammation.

Klytia also introduced a number of liquid powders into its inventory such as Fleur de Poudre Liquide No. 110 in Ivoire, Rachel, Bistre, Ocre, Chair, and Ambrée shades and Sève Madrilène No. 260 in Blanc, Rachel, and Chair Naturelle tones. Both products arrived in the late 1920s.

Lipsticks and rouges

As previously noted, Klytia had a rouge in its inventory in 1899. By 1930, Klytia had over twenty different liquid, cream, and compressed powder rouge in its product list. One of these, Pastels Comprimés Q. de la Tour, refers to Maurice Quentin de La Tour [1704-1788], a French painter known for his work with pastels.

Clients could also chose from a wide range of shades, the largest being for the powders. For example, Fard Sec No. 271 came in Blanc, Crème, Rachel, Naturelle, Rose, Chair, Ocre Rosé, Pêche, Rouge 8, Rouge 18, Mandarine Blonde, Mandarine Brune, Rouge 24, Rose 12, Vermillon des Anges, Pêche, Pétale de Roses, Orange, Mauresque, Ocre A4, and Ocre Oriental shades. In some cases recommended shades were selected by hair colour. For example, the liquid rouge Crème de Rose No. 221 came in two shades No. 1 for brunettes or chestnuts and No. 2 for blondes or redheads.

Some have suggested that Klytia added its first lipstick in 1910 but I have been unable to validate that date. However, by the late 1920s, it was selling a number of lipsticks in sizes ranging from the thick Crayon Doré Tournant No. 485 to the thin Crayon Plat No. 234. Some used a push-up mechanism but others look to have been twist-ups. All were apparently refillable, were flavoured using ‘natural fruit juices’ and came in Vif, Incarnat, Foncé, Mandarine, and Cerise shades. Klytia also sold an uncoloured ‘lipstick’ to prevent lips chapping, a lip cream Pâte No. 85 sold in a pot in a Strawberry shade and two liquid lip rouges, Rouge Fixateur No. 235 and Gouttes de Rose No. 236, packaged in a bottles together with a brush. Rouge Fixateur looks to have been a red while Gouttes de Rose turned pink after it was applied which suggests that it used a bromo acid as the colourant, a dye that began to be used in indelible cosmetics in the 1920s.

See also: Indelible Lipsticks

Eye make-up

As mentioned earlier, Klytia had a mascara in its original range that could be used on both eyelashes and eyebrows. Beauté des Yeux No. 229 was a cake (block) mascara that came boxed with a brush, a typical packaging for this type of make-up. In late 1920s, it came in Noir, Brun, Châtain, Blond, Outremer, Bleu Vierge, and Bleu-d’Azur shades.

See also: Cake Mascara

Along with Beauté des Yeux, Klytia also sold Noir Liquide No. 350, a liquid mascara; Kohl du Harem No. 309, a kohl; Crayons des Yeux No. 237, eyebrow pencils in Noir, Brun, Chôâtain, Blond, Bjeu, Mauve, and Bleu Céleste shades; and a fixative, Cosmétique Fixateur No. 50, to help control and shape the eyebrows.

See also: Liquid and Cream Mascara and Kohl

For those that wanted to colour their eyebrows more permanently there was Pâte du Liban No. 183, a paste used like a poultice to dye them. As far as I can tell Klytia did not dye eyelashes.

Klytia also added cream and powdered eyeshadows in shades that included Gris, Bleu, Blond, Châtain, Bistre, Noir, Violet, Vert-Pré, Vert Ophélie, and Gris Bleu.

Preparations de Grande Beauté

Cosmetics in this group included a number of what are known in English as enamels, a class of cosmetics that has long been superseded by other forms. Most can perhaps be best described as a combination of concealer and foundation so could be used under powder. They were designed to hide facial imperfections such as spots and scars, and make the face look younger by smoothing the complexion and concealing wrinkles.

See also: Queen Alexandra and Face Enameling

The top products in the Grande Beauté range were Royale Beauté de l’Impératrice, an evening cream for women with dry skin, and Nouvel Émail No. 307 for women whose skin was oily. Both products came in Blanc, Crème, Rachel, Bistre, Chair, Ocre, Mauresque, and Naturel shades.

Above: c.1928 Royal Beauté de l’Impératrice No. 310 – bottle, applicator, and cardboard container.

During the day, women with dry skin were recommended to use Émailline No. 212 in Blanc, Crème, Rachel, Bistre, Chair, Ocre, Mauresque, and Naturel shades while those with oily skin were to use Le Blanc-Régence No. 275 in Blanc, Crème, Chair, Rose, and Naturel shades.

Klytia also made two exotic Grande Beauté preparations for women in warmer climates such as South America – Glacis Cipaye No. 140 and Rosée Cipaye No. 130. Both products came in warmer Péche, Ambrée, and Curvrée shades.

The most unusual product in this this group was Émail de Mes Vingt Ans No. 295, an enamel applied with a brush and feathers.

Émail de Mes Vingt Ans No. 295: Its use is simple and quick. Apply it with the brush and then smooth it over the face with the special feathers. It causes a pleasant feeling of freshness while hiding spots and shadows, reviving the most damaged of complexions.

Beauty spots

One last make-up item that should perhaps get a mention is the Mouches Pompadour No. 456, beauty spots made in different sizes from black or brown velvet or black silk.

See also: La beauté c’est toute la femme (c.1927)

Above: 1927 Klytia stand at the Exposition de la Coiffure et de la Parfumerie in Paris. The two figures manning the stand may be Victor Merle and Marie Valentin Le Brun.

Future prospects

Things were looking fairly rosy for Klytia as the decade drew to a close. Unfortunately, it was soon to be hit with a number of problems not the least being the stock market crash of September, 1929 which ushered in the Great Depression.

Timeline

| 1895 | Traditional date for the establishment of the Institut de Beauté. |

| 1898 | Factory opened in Neuilly-sur-Seine. |

| 1899 | Société Merle et Valentin formed. Institut de Beauté salon opens at 26 Place Vendôme, Paris. |

| 1901 | Société Merle et Valentin dissolved. |

| 1925 | Business sold by auction to Valentin Le Brun. |

| 1926 | Paris factory moved to Levallois-Perret. |

| 1927 | New Products: Les Produits Néoplastiques. |

| 1928 | New Products: Cold Cream Savonneux à la Violette No. 338; Fleur de Poudre Liquide No. 110; and Sève Madrilène No. 260. |

| 1929 | Etablissements Klytia S. A. created in Paris. Klytia Corporation founded in New York. |

Continued onto: Klytia (1930-1945)

First Posted: 18th January 2024

Last Update: 6th September, 2024

Sources

Klytia. (c.1927). La beauté c’est toute la femme [Booklet]. France: Author.

Elise Marie Le Brun [1860-1930] a.k.a. Madam Valentin Le Brun, and Madam Merle.

1901 Institut de Beauté cosmetics available in Wanamaker, New York.

1902 Institut de Beauté, London.

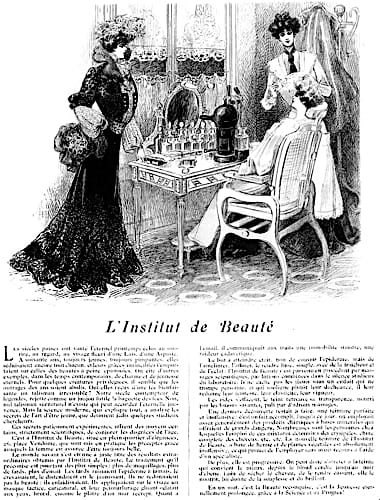

1903 Institut de Beauté advertorial.

c.1903 Institut de Beauté. Recompenses obtenues depuis sa fondation. Fonde en 1899. Trans: Awards obtained since its foundation. Founded in 1899.

1906 Institut de Beauté.

c.1908 The old Hôtel de Nocé at 26 Place Vendôme. The Institut de Beauté can be just seen on the left on the street leading to the Rue de la Pais. The luxury jewellers, Boucheron, are on the ground floor.

c.1908 The Institut de Beauté at 26 Place Vendôme near the entrance to the Rue de la Pais.

1908 Institut de Beauté (Türkiye)

1908 Perfumes from the Institut de Beauté (Britain).

1908 Institut de Beauté Trinite Methode.

1909 Institut de Beauté.

1909 Treatments for the breast.

Main d’Isis (Hand of Isis) No. 2141. It could be used to massage the face or body or to rub an abrasive depilatory powder over the arms or legs.

1910 Institut de Beauté Nice.

Institut de Beauté Poudre Klytia No. 1.

1910 Institut de Beauté.

1910 L’Institut de Beauté.

1910 Madame Victor Merle.

1913 Institut de Beauté.

A scene from the ‘L’Institut de Beauté’ at the Théâtre des Variétés, Paris which opened in 1913. The play may have helped cement the term as a reference to a beauty salon in Framce.

1913 Institut de Beauté.

1918 Institut de Beauté.

1921 Institut de Beauté.

1923 Institut de Beauté (New York).

1925 Klytia treatment method (New York).

c.1926 Les Établissements Klytia. Note the two factory addresses, the addition of Klytia to the shield, and the absence of Victor Merle’s name.

1927 Institut de Beauté.

1927 Le Célèbre Institut de Beauté.

This looks to be Crayon Monaco Doré No. 485 sold in Vif, Incarnat, Foncé, Mandarine, and Cerise shades.

c.1928 From left to right: Émailline No.212, Fleurs et Farines de Mon Moulin No. 266, Nouvelle Huile Tonique aux Fleurs d’Orient No. 25, and a package probably containing Crème Djaviden No. 162 and Poudre Djaviden No. 174.

Poudre Djaviden No. 147 in a glass container designed by Julien Henri Viard [1883-1938] was also available in a more conventional cardboard box. Crème Djavidan No 162 which was sold in a similar glass container could be used as the powder base.

Émail de Mes Vingt Ans No. 295 with brush and feathers.

c.1928 Left to right: Ma Poudre Préféré 1830 No. 257, puff, and Poudre de Riz Eulalia No. 5.

1928 Institut de Beauté (Germany)

c.1928 Beautician and client in the Institut.

Poudre Elayne No. 142.

1928 Crème Mousse-Mousse No. 130 (Italy).

1928 Institut de Beauté.

1929 Le Célèbre Institut de Beauté.

1929 Klytia Corporation (USA).

1929 Klytia (Germany).